Getting2Alpha

Getting2Alpha

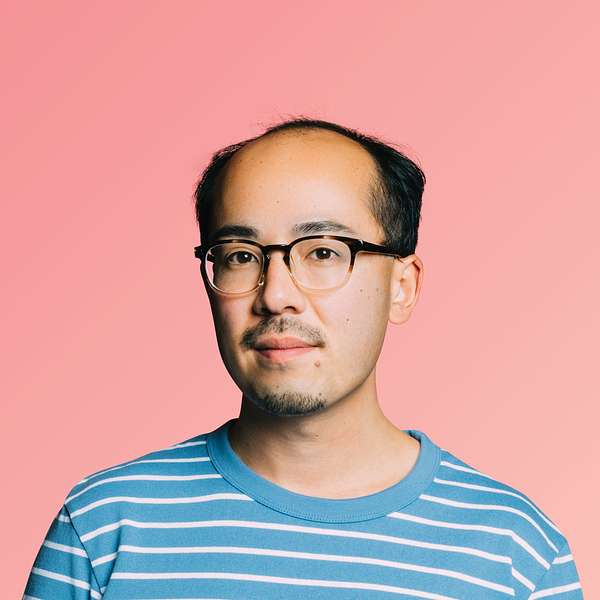

Adrian Hon: Making Zombies, Run!

Adrian Hon is an English writer and game designer, known for his expertise in alternate reality games and transmedia storytelling. As the CEO of Six to Start, he created the bestselling fitness game "Zombies, Run!" and authored books like "You've Been Played" (2022) and "A History of the Future in 100 Objects" (2020). He studied neuroscience at Cambridge, UCSD, and Oxford, and has spoken at TED, Long Now Foundation, GoogleX, and Disney Imagineering.

Check out the video here: https://youtu.be/n8Nm7YEwfCI

[00:00:21.1]

Amy: Adrian Hon has a big imagination.

For over 20 years, he's been writing science fiction and designing alternate reality games, including the mobile hit fitness game, Zombies Run.

This game has carved out a unique niche as an audio only story game that's attracted 10 million loyal players.

And it all started from a chance remark.

Adrian: She said that she'd just joined an online running club.

And they'd asked all the people in the club, why do you want to run? And some people said they wanted to get fit, other people wanted to lose weight. And one person said that she [00:01:00] wanted to survive the zombie apocalypse. And um, I was like, zombies, I'm kind of sick of zombies because they're overdone. But it became really obvious that it was just a really good premise for running game because you would always be running,

Amy: Join us as we explore how this alternate reality pioneer built an innovative, long-lasting hit.

Amy: Welcome, everyone. We're here with the amazing Adrian Hon. I'm so excited to have you here. Thanks for joining us, Adrian.

Adrian: Glad to be here. Thank you.

Amy: Let's get started by just giving us a little glimpse into your work life. You're a game designer, you run a studio. I'm sure that you're busy with lots of different things, but can you give us just a peek into what your workday looks like, what kind of things you do, who you work with? The kinds of decisions you might be making.

Adrian: [00:02:00] Sure. well, my company Six to Start has grown quite a lot in recent years. It's 25 people now. And, I am CEO of that. And so most of what I do on a day-to-day basis, is CEO of staff, which is to say, being the kind of final port of call for management issues, an, HR issues, and things like that.

At the same time, I've got a really good sort of senior team and they're able to handle a lot of that. And so, I do like spending a lot of time on creative stuff, on technical stuff. So today for instance, I was, putting together drafting a spec for a bit of our Marvel Move project, about how some dialogue works there.

Then I'll be reviewing, audio and video that our other teams are put together, and, you know, an artwork. Obviously, we've got frequent meetings with different teams here, so make sure people are on track, people understand, what we need to do. People aren't blocked. And obviously [00:03:00] we are spending a lot of time talking to our partners, so, I had to call a Marvel today, have weekly calls with them, making sure they know what we're up to.

And, I do try to spend, an hour, uh, a day probably, maybe a bit more, um, just having one-to-ones with everyone in the company just to make sure, they know what's going on and they can ask me any questions I've got about what we're up to.

Amy: All right, so that is, it sounds like exactly what a CEO would do.

So let's wind it way back. How did you first get started in tech and gaming and design? Where did that interest come from?

Adrian: Well, I mean, I've always been interested in tech. My, my dad was a professor of engineering at university, and so he would bring back, you know, computers, like in the eighties and early nineties, from university. So I got to play around with PCs and BBC Micros and with BBSs and EMS when I was pretty young.

And that's how I got online, first to BBSs and then to the [00:04:00] internet. And so that was really influential, for me, just being able to talk and then work with people, around the world. And then, I would say, I started making, fan games and little online projects in my teens, but professionally, I really got into gaming, in about, 2001 when I started playing the first alternate reality game, which was a game that mixed the real world and phone calls and emails and online things.

With, with the web, and that was a promotion, for the movie Artificial Intelligence by Steven Spielberg back in 2001. I thought it was amazing. I loved it and I started writing about it and I kind of wanted to become, a game designer as part of that.

And that's how I got into it.

Amy: And what was your first game design job?

Adrian: My first game design job was at Mind Candy. it was a, it is a games company based in London. And [00:05:00] I got hired, in 2003, 2004, while I was doing a PhD in neuroscience at Oxford. And they wanted me to help create an alternate reality game that was kind of a big global treasure hunt, that would sort of mix a real world on online.

And I joined as a sort of basically lead game designer and producer. I mean, it was a small company. I was like basically employee number one. So did everything from, helping hire people and set budgets to open the mail and hoover the floor and things like that which is fun if you're young and you have that energy.

I was like 22 or something, 21 at the time. and then I did that for about three or four years.

Amy: So, did you drop out of your PhD program?

Adrian: Yeah. I'd been doing it for about a year at that point. And, was a good lab, a good team that I was with at Oxford, and I, didn't really have any problems with them. But I thought games was even more exciting and this [00:06:00] opportunity to join the games company and be in, in the ground floor, didn't come along often.

And I figured that if it didn't work out, I could just go back and do another PhD. So, I had a backup option at least.

Amy: There you go. So, you did that work, and it sounds like you were a designer, you were a producer, you were kind of doing everything.

Adrian: Yeah. Yeah, that's right. It was such a small company that suited me well because I didn't like doing lot of different things. I liked learning. We were, we didn't really have a lot of investment. But the nice thing about alternate reality games is that, they kind of absorb everything you put in them.

So, if you want to do a puzzle that's based around, you can do that. If you want to do a phone tree, you know that people have to call up to go and get a secret code, you can do that. You can kind of do anything you want, placing weird adverts and newspapers. But eventually, you know, it grew to a big company, and we had a big team working on it and hundreds of thousands of pairs.

Amy: Amazing. So how did you come up with the idea for [00:07:00] Zombies Run and then start to develop it? It's such an unlikely hit, but there it is.

Adrian: Well, zombies run, came at Six to Start. So that was the company I set up after leaving, Mind Candle. And it came like a few years after we founded the company because of the first few years we'd been doing work for hire. For companies like the (B) BBC and Disney and Microsoft and so on.

And so we did that. We won a bunch of awards and had a really good reputation in the industry. But, um, we just weren't really making any money. It was very challenging, especially for a small company at that time. And so, I was kind of wanted to make our own game and I'd been starting to run more around then, as an exercise.

And the iPhone was about two years old at that point, maybe two, three years old. And so, you had apps that, that you could use for running like Runkeeper, already and Nike+. And it was [00:08:00] surprising to me that no one had made like a good running game yet, or good running sort of gamified running app.

There'd been bad ones, but there hadn't been good ones. So, I was talking to, a friend and frequent collaborator, Naomi Alderman, who is an author, and she has a big TV show out in the moment called The Power on Amazon. And I mentioned that I was interested in making a running game. And she said that she'd just joined an online running club.

And they'd asked all the people in the club, why do you want to run? And some people said they wanted to get fit, other people wanted to lose weight. And one person said that she wanted to survive the zombie apocalypse. And um, I was like, oh, that's, that's funny. And then we kind of talked about it a bit more.

I was like, zombies, I'm kind of sick of zombies because they're overdone. There's so many zombie games, so many zombie TV shows and movies. But it became really obvious that it was just a really good [00:09:00] setting, and really good premise for running game because you would always be running, obviously away from zombies, but also, to collect supplies, to rescue survivors, to scout in the area, to send messages, that sort of thing.

It seemed like something where we wouldn't have to try hard to figure out a reason for you to be running, and the game design kind of flowed really easily and crucially. That game design seemed like something that was in the capabilities of the team that we had because it was a really small company.

It was like, by that point we'd sort of shrunk about three or four people. And so, we didn't have like 3D artists, we didn't have really any money. But we had, you know, mobile developer, we had a great, writer. He had a great audio director and so I was like, well, we have these things, and we have this design and they both fit each other really well.

And so this seemed like a really good opportunity.

Amy: Wow. That is a great story. did you have to raise [00:10:00] some money to build it or did you just bootstrap building it?

Adrian: We did put on Kickstarter, we put it on Kickstarter in I think August 2011. And that was pretty early, in Kickstarter history. We were one of the very first Kickstarter projects in the UK full stop. And we ended up being one of the, we ended up being the biggest video game Kickstarter at that point, which was not really that big.

But it was still kind of notable. We raised $72,000 for about 3,500 people. And we got press cause like on BBC News just because we were a Kickstarter project. So we, we were sort of very hyped and, if you make games even, 10 years ago, simply $2,000 is not a lot of money.

It's not really enough to make a game on. But, just seeing that level of interest from strangers, who'd never heard of [00:11:00] us. And that kind of confidence when people who are like, wow, this sounds like a great idea for a game that doesn't exist yet, really gave us the confidence to, to devote, the next six months, into just dedicating all our time and energy to, to getting out on time and, we managed to do that.

And, um, yeah, it's interesting thinking about the funding situation, because, I had been talking to, I have talked to VCs and investors in the UK before then, and I know that what they would've asked is, well, what are the comparables, what other games out there are there like zombies run and how much money have they made? And the answer would be there's nothing out there like it. And so we have no idea. And so they wouldn't have given us any money. So, it was pretty clear that going the kind of traditional route was just not gonna work for us. We would've to use crowd funding and that's what we ended up doing.

Amy: What were some of the struggles or [00:12:00] surprises as you built out your game? Because it's a great premise. Love the focus on audio. All of that's great. You actually built and shipped it and now it's, been updated many times. What were some of the things you ran into that surprised you along the way?

Adrian: I mean, so many things, but one of the—I guess I’ll sort of hone in on two things. One was that I was just really worried that other companies were going to copy the idea of combining storytelling and audio and exercise and kind of get run over by Nike or the rest. And that didn’t happen in the end.

And I think the reason it didn’t happen is because the sort of traditional fitness companies like apparel companies like Nike and Reebok, it’s just not at all within their brand or wheelhouse to even conceive of making a game, let alone a game that they would sell for money. It’s just not something that they do because they don’t really have to. I mean, that’s not how they make money. How they make money is by selling t-shirts and trainers. And I think if I knew that, if I could go back in time and tell myself that, I would probably enjoy myself quite a lot more instead of being worried about the competition, which didn’t, didn’t exist.

The other thing that was surprising is I thought that we would make Zombies Run for like one or two or three years and then we would just go make something else because we never worked on a game for that long before. Zombies Run is still running. It’s going to start season 10. It has started season 10 this year, and we’ve been making it for 11 years, going on 12 years now.

And what is surprising is that—I mean, and I shouldn’t be surprised, but because it’s a fitness product, people really began to rely on it for their health. And so instead of just being like, oh, that was fun, now I’ll play something else, they would email us saying, you really changed our [00:14:00] lives, and you helped me recover from this illness.

Or you are the thing that gets me exercising in the way that nothing else can. And it almost felt—I mean, it felt incredibly rewarding, obviously, even more so than making a great game because you realize that you’re doing something that is really unique but also feels a little bit like you have a responsibility for these people.

Because they’re like, well, when’s the next season coming? When’s the next expansion? And their health is tied to it. And so that’s mostly good. It is great to be working on something that is so good for people, but it’s also a bit of a burden as well.

Amy: Yeah, I bet. So how does the season work? It sounds like you evolved this idea of having seasons. You're now on season 10. What's a season? How does it play out?

Adrian: Well, the way Zombies Run works is a bit different from any normal game. In that you change into your t-shirt and shorts, you put your headphones in, you start Zombies Run, and you begin a mission. Then you’ll basically get this kind of [00:15:00] audio adventure, which is a little bit like a podcast, a little bit like an audiobook, but kind of like first person, intertwined with your own music.

Behind the scenes, it’s represented by a bunch of MP3 files fundamentally, along with accompanying code that dictates when zombie chasers should appear or when certain supplies are dropped during various other game events. Each season comprises a collection of missions, similar to a season of a TV show. Initially, it was about 20 missions long, but we later extended it to 60, which turned out to be too long because it was challenging to keep up that pace. Now, seasons are more like 30 to 40 missions.

Amy: How often did they drop?

Adrian: Oh, every year like, like a TV show or traditional TV shows, at least.

Amy: Wow. So now I wanna ask you about the thing I'm so excited about, which is your [00:16:00] new project, Marvel Move. I'm very excited that you can talk about it. It's been announced just a few weeks ago. How did that product come about? How did you get connected with the Marvel folks?

Adrian: We’ve been talking to Marvel for four years. They had seen Zombies Run, and a bunch of their people were fans of Zombies Run. And they’d beat players, and that was awesome. They’d seen some of the other fitness games we’ve made, like Superhero Workout, and they were kind of half like, well, you know that we own the superhero trademark, so be careful.

But also, they just thought it was cool. And so, we’ve met with them like, I mean, for probably 4, 5, 6 years, even maybe longer, just talking on and off about, oh, it would be cool to do something together. It would be cool to make some sort of fitness experience, using Marvel characters, using Marvel stories. And probably like two, three years ago, we kind of hit on an idea for Marvel Move, doing something [00:17:00] with the kind of Zombies Run sort of style of running engine and adventure. We sort of pitched it to them, and now we’re sort of collaborating on this.

I’ve never worked on anything quite like this before. I don’t think they’ve worked on anything quite like this before either. It’s a really unusual project. I don’t think Marvel’s done like a fitness thing like this, especially anything with subject kind of focused on audio storytelling or storytelling.

But it’s been really—it’s been really good. I mean, they’re genuinely—I mean, of course, I would say this, but they’re really good partners. Really interesting creative partners.

Amy: So how does that collaboration work with writing? You yourself have a whole background as a writer. You've clearly done a lot of professional writing. You've got writers on staff, right? At your game company, your genre, but now you've got Marvel, a beloved brand that they control. So, how does that work with the creative, that collaboration?

Adrian: [00:18:00] Well, it’s interesting, they know the Marvel Universe and the Marvel characters and stories best, and so they wanna make sure that if we are going to have a running adventure that features Daredevil, that we don’t do something that is completely. In the opposite direction to people’s understanding of their, through the comics in particular, but also through the TV shows and movies, right.

That would be a waste of time for everyone. And similarly, for the X-Men and so on. So, they bring that kind of really deep knowledge of who these characters are and what they would do and what fans love about them and what’s been tried and what’s worked well and what hasn’t worked well.

At the same time, they know that the kind of storytelling that we’re doing and the kind of experience that we’re providing, involv movement is so different to almost any other kind of thing that they’ve done that, that they need to trust us to, come up with [00:19:00] stories and find writers who can do that.

So, to be really specific, I think that the kind of storytelling that you have in Marvel comics, is, it’s not a million miles to sort of port that to TV or to movies, right? It is this kind of a story that you’re watching, and of course that’s something that they’ve done literally with movies and TV shows, and suddenly we’ve audio books and, podcasts and audio dramas.

I think that with Marvel move, the difference is, whereas like a TV show might be 30 minutes and a movie is two hours, and an audio drama is like 45 minutes, the amount of audio in our, move episodes is about 15 minutes split up into different scenes separated by story. And also you are experiencing this while you’re running, right?

You’re not just sitting at home or in your car listening to it. Furthermore, you are a character in the story. You are hearing Wolverine talk, you’re not like [00:20:00] watching a TV show. It’s almost like they’re talking to you. You are in this kind of first-person adventure. And so that, to that degree, it’s a bit like a video game, except it’s less interactive.

And so it all ends up being kind of pretty idiosyncratic, and that means that they need to trust us. And so what we ended up doing was we are using some of our own writers who have been working with Six to Start for a while, and we’re also using some of their writers who have been working on Marvel comics for years.

So, like Teeny Howard, has written for the X-Men comics, and our creative lead at Marvel, Ryan Pen. I mean, he’s like a genius. He’s sort of read most of the tens of thousands of Marvel comics that have ever been published. And so it requires a lot of trust and a lot of knowledge of, and respect for each other’s skills on both sides.

Amy: So you've [00:21:00] built a writing team that's got both six to start folks and Marvel folks on it, and they're collaborating sounds like. So that's super interesting, that creative process that you just described. And I mean, I think that speaks to very, very well for your studio to be able to one, cut a deal like that and two collaborate in that way.

There's a lot of different gaming studios and they work in different ways and you've clearly built a studio. That one knows what you can do. You said something interesting earlier that I wanted to just touch on and given a little oxygen, which is that when you decided to do zombies run, you looked at your team and you said, what can we pull off?

Who's on the team? We got audio, we got a writer. We don't have graphics. What can we pull off? And it's pretty impressive that for somebody that young, you were thinking that way. [00:22:00] Many, many games and teams and studios are very ambitious, and they bite off more than they can chew and they really don't look at.

The match between their team's skillset and a particular game genre and what they can do. You did I'm wondering how you, at such a young age, were thinking in that sophisticated way, in a way it's obvious, right? Well, of course. Do what you can pull off. Do you feel like your time at, perplex City helped you with that kind of scoping?

Adrian: I don't think it's like super magical. I think most people never get the opportunity to start and end the project and see what happens, actually. Which sounds weird, but it's also just true, like most people don't get an opportunity to work on a project with multiple people or even just themselves.

And release it to the public and get feedback and maybe get paid or lose money or whatever. I started doing that when I was like 14 or 15. [00:23:00] I think most people start doing that when they're 21, right? Or they're 22. It's pretty simple. And so like I just kept doing it again and again because I like doing it.

I think it's really tragic that, the times it people should be doing this sort of thing when failure doesn't mean you're going to be bankrupt. And so if you can do that at high school, if you can do that at university, then that is a perfect time to do it and it has to be like a real independent thing rather than something that is kinda too far in the kind of the guardrails.

Cuz otherwise it's not a real thing. So that's kind of the main thing. That's how I was like, well, I have a really good understanding of what I can do personally within two hours of work, within two weeks of work, within two months of work, I know what I can do. And then it was like, okay, now I can, now I know how to figure out what, because that's, that's, you know, like how, how do you motivate other people?

And so when someone tells you, well, I think I can make this piece of artwork in two weeks, it's like, [00:24:00] well, do you really know? How can you tell? And so that's a thing that I learned when I was a teenager, just from working with like strangers on the internet. Then, working at public City showed, okay, here's the limits of what is possible.

If you have this team and you have money, but not unlimited money, and you're basically allowed to do literally anything you want. Then, it was like, well, let's go and try and send, this package to a thousand people around the world. And I think that other companies, it's like, wow, that seems complicated.

How do we do this? How do we post this? And it's like, well, I can just go and Google that. I can find out the answer or we can just do it ourselves. We'll just go and sort of, execute that ourselves. Or during one live event, we had like three helicopters flying around the, um, palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco, which we hired one of our events.

And people are like, wow, how do you do that? It's I dunno, we call up a helicopter company and see if they can do it, and then you go and email the council fine arts, and, find the cost. I [00:25:00] think a lot of people are a little bit kind of scared to find out how to do these things. And, after you try, I mean, it is scary the first time you do it and the second time you do it, but after you've done it 10 times, it's not scary anymore. So, it's just kind of trying to get that practice. But like, very specifically for Zombies Run. I mentioned that the prior to that we had been doing a lot of work for hire for, the DBC and for Disney and for other clients.

And that was just a real case of speed running. Our ability to create projects quickly on time, on budget, if we had taken a commission to make a game for the BBC. For a TV show that had a defined air date, and we could not hit that deadline, we would be in deep trouble. And so, you just get really good at project management and really good at understanding scope and managing the relationship.[00:26:00]

And so that meant that when we did Zombies Run and we did the Kickstarter and, we said this game is gonna be out within six months. I mean, most Kickstarter, a lot of Kickstarter games never released at all. And a lot, and most of them never come out on time. Not even remotely close to being on time.

We were on time, but on budget. And it's because, well, we were just knew how to do that. We'd had so much practice. So no one's born knowing the staff. It's just having a lot of practice, I think.

Amy: That's fantastic. That's such a great story. And it reminds me of other friends of mine who have run work for hire game studios. They're incredible at scoping cuz you have to be, or you go out of business.

Adrian: Yeah.

Amy: That makes a lot of sense. Now, one of the things every game designer struggles with and deals with is tuning.

Tuning your game, making sure it's what people like. You've already told us some tuning stories. You add too few missions, then you add too many missions. Then you figured out how many missions to have in a [00:27:00] season. You figure it out iteratively, but it's really hard to get into customer's heads. You can't just ask them, right?

You have to watch them do things and learn from that, et cetera. So, what are your favorite go-to techniques for testing and tuning your games with customers?

Adrian: Well, I mean, the interesting thing with Zombies Run is that we, we really have extremely flexible settings for users. Cause everyone is so different. And so it is, when it comes to their fitness, right? There's a much wider range of abilities, and preferences than there would be for, i don't know, call of Duty or something where it's easier for people to kind practice and get up to a certain skill level.

For Zombies Run, we've got people who, would find it difficult to run one mile. And we've got people who find it trivial to run 40 miles, right? And so, you have to go and have settings in [00:28:00] the game that allow people to adapt the experience to what they want to do. And of course, you have defaults and we wanna make sure the default is something kind of fairly sensible, about like zombie chasers and things.

And part of that comes down to just like trial and error. And part of, i mean, that's a benefit of running a game for 10 years, is that you eventually figure out, okay, well this seems about right, basically. It's harder if you're doing it. When we were designing zombies run for the first time, I mean, we didn't have time to like de to test it.

It was just me running around with it and thinking, wow, this seems fine. And then we would tweak it later. But yeah, with other games, it has been through play testing. But I think, and all of it has just been through the game designers and through myself thinking, well, this seems about right.

I think one of the things that I am good at as a game designer is that i get, much more frustrated and much more annoyed and I’m much more impatient, with things [00:29:00] than a lot of gamers, which is to say if something ends up being too difficult or boring, or slow, then I will give up much faster than most gamers.

Which means that if I design a game than i want it to get to the point really quickly. I don't wanna waste people's time. And I’d rather make a game too easy than too hard. And I think a lot of gamers would disagree with that. They would probably say, well, actually, I find it boring if a game's too easy.

And I’d say, well, I think the games that i make are not boring. If they're too easy. Cause they, they have, they're more about the world and the story than about the challenge.

Amy: Yep. Makes a lot of sense. So, one of the big topics in my circles among game creators is user acquisition and all the changes that have happened in the last year. With the Apple App store changes, locking down on privacy, making user (ac) acquisition much harder for a lot of people. How has that affected you with zombies around and now Marvel [00:30:00] and your studio?

Like how are you navigating these UA changes?

Adrian: Yeah. it's a good question. I was gonna say, we've been lucky. I don't, I wouldn't say call it luck. Zombies Run has always been a very different game to. The most popular games out there, premium free to play games and things like that. Cause we have basically spent nothing at all on advertising or UA or marketing.

And i'm not saying that as a thing that i think people should necessarily copy. Cause I don't think it's gonna work for most games. But Zombies Run is so unusual. As in you can't really say, well, if you like X and you'll like, y it doesn't work for Zombies Run. You could say, well, if you like Angry Birds, you should play this other game.

People will understand what you mean. But cause Zombies Run is kind of the only one in this category, then you can't sort of depend on that. Instead, how to do is rely on word of mouth. And that's how most people find about us. They Google, they hear about playing Zombies. Run. And their friend says, I [00:31:00] had a great time.

This is how it got fit, or that sort of thing. And then they googled it and they download it and they try it. And that has meant that we are kind of completely immune to any, UA changes or any kind of privacy changes because we never really benefited from that in the first place. It really has been word of mouth.

Amy: Wow, that's amazing. Do you have any kind of community that you run player community, just to keep them engaged, but also maybe they, get feedback from them?

Adrian: Yeah, we do have a private forum that we have for our kind of VIP subscribers but also there's like an unofficial Reddit and there's Twitter and it's Instagram. That's all the usual places. And I’m fairly active. Like I, I keep track of all of them and I will interact with people, if people have got questions and so on.

I used to answer most of our support emails, myself. And so I’ve probably answered about 10,000 support emails myself. Which is, I [00:32:00] think, useful for people to do just to know what their players think. And I would encourage people to do that. It's a good way for us to figure out what people are up to, what people think.

At the same time, those are always the most kind of passionate people and they aren't, frankly, very representative of most of the players. And so I do want to make sure they're happy because, they're important at the same time. They'll often say, can we have this feature or that feature?

And we're just like, well, maybe, we're not gonna be driven by that. I think these days, it is pretty normal for games go into early access and they have discord, chatrooms and things like that, which I think probably is like very motivating and probably quite exciting.

Um, it fills me with a certain terror. The idea of having a Zombies Run discord, I’m just like, wow. I feel like I’d be on that all the time and I would just end up being a little bit too influenced by the 200 people or 500 people, the thousand people who spend a lot of their time there, as [00:33:00] opposed to the hundreds of thousands of people who are not interested but are still like important players.

So I think that's something that, if you know how to engage with the player base in a sort of healthy way, in a limited way, that's great. But I think particularly for like inexperienced developers, it's really easy to think, wow, I’ve just gotta make these people who are writing something me now as happy as possible.

And, yeah, that, that is not necessarily, a good idea.

Amy: Yeah, I've seen that same dynamic happen on MMOs, where we have a forum of the most devout players and the devs are in there and everybody's chatting. But then we miss, the, in the bell curve, we're missing the big lump in the middle, and you need different tactics. So Adrian, so far, we haven't used what I call the G word gamification.

And one of the things I love about you is that your work is often pointed at as an example of [00:34:00] gamification, and yet you built a great running game. You know it, you didn't do what most people would do with gamification. And of course, you know that's a semantically blurry word. how do you think about what you've accomplished, what you do. Marvel Moves, Zombies Run, these games, how do you think about that? When people say, oh, you're doing gamification, do you say, thank you, I am, I'm doing it the right way. Do you differentiate? How do you parse that yourself?

Adrian: I mean, I think that it, it is, gamification by the term that most people understand it, right? It, it is, you know, applying game design elements to a sort of non-entertainment thing. And so I don’t blame people, I suppose. I’m not surprised when people say, well, this is a Zombies Run.

Well, it is gamifying running. I think that, gamification has always had a bit of a pejorative slant [00:35:00] in the, people are like, well, I like gamifying this, cleaning my house by adding points and badges and things like that. I’m like, well, what we do is kind of harder than that and more, more complicated, and I think more effective than that.

And so I think that the reason why I would usually caveat or sort of elaborate on people saying, well, Zombie’s Run is just gamification. It’s I’d say, well, I think we’re kind of more complicated and better, and more successful than most gamification out there.

I think a lot of gamification out there is very superficially designed and even worse, just not very effective. It would be one thing if you could add points and bands and missions and theater boards to activities. And then people loved it and it did motivate them, but I don’t think it actually does. So, people have tried that were running and they’ve tried that exercise and it’s just not a very kind of like long-term effective intervention.

So that is, that's kind of where I would draw the distinction for most gamification that [00:36:00] people encounter.

Amy: So as a game designer, at one point you are a brand new game designer. Now you've got a number of gains under your belt. You're much better at scoping you're negotiating deals with IP, et cetera. I'm sure a lot of people ask you questions about game design. you hire new people in your studio, you might go give a talk, et cetera.

What are some of the really common mistakes that you see junior game designers make or first-time game designers make that you just kind of shake your head and go, yep, I, you're gonna have to learn not to make that. What are those mistakes that, it would be great if people could learn from and watch out for.

Adrian: The main one, which I think everyone does and I did is just trying to do too much basically. And even experienced game designers do this, I do as well where you have this idea that I've always wanted to make a game where you can fly spaceship and you could repair the spaceship and you could get out the spaceship and do these things and shoot aliens and then, and it's okay, [00:37:00] maybe you should just do one of those things and then see how that works because the game doesn't get better if you can do more things actually, that's just a feature list.

And so it is so hard to make a game that does one thing well. That, that is fun and doesn't kill you making it, and that, that makes money that like, that you don't even need to be original, honestly. As, as long as you do something that like works that you've already been successful.

And so I think I, it, it is weird to say this, but I kind of think that cause of games, it's possible to be so kind of innovative with game design that it's become expected that new games and successful games should be really different and should be really innovative. And I think that you can innovate in different ways.

It doesn't have to be through game design, it can be through art, it can be through story, it can be through controls and things like that. And so I think we, the thing that I think [00:38:00] happens with a lot of kind of game design textbooks and things like that is that we kind of. Oh, what if, who are to go and do in a different way?

And it's that is cool, but it ends up, making things that, that I think, yeah, just making it really challenging and probably harder than it really needs to be. Of course, I love it when I discover like a new genre and something that is, a kind of game that is, is so different. But, people still like crosswords and that's just doing the same thing over and over again.

But it's a really good game design.

Amy: Yep. Over scoping. It's the perennial problem. So, Adrian, one thing I've been really enjoying is you have a newsletter where you review games you're playing. And a lot of times in your newsletter you play something, and you know you're somewhat critical, which I love. Very educational. What games out there right now, do you admire? What games have you played recently, or maybe even not so recently that you really admire that you think? Maybe you'd be influenced by it, or you just think there's [00:39:00] things to learn from.

Adrian: The game that I played most recently that I keep kind of keep on thinking about is this VR game called The Last Clock Winder. I'm really interested in VR, even if I think that the most of the stuff I played is not really that good. And The Last Clock Winder is like a puzzle game.

Basically you are going, it's such a weird game actually, but basically more or less you're going through this kind of abandoned factory and you have to kind of motion capture movements, your own movements and record them for robots to perform. And what you'll end up doing is sort of recording the movement for like a dozen robots to sort of work together to pass components and assemble them.

And, it's a little bit weird and the first time I tried I was like, I don't really understand this game, but people say it's really good, so I'm gonna give it a go. And after I got half an hour or an hour again, I was like, this is the greatest VR game [00:40:00] anyone has ever designed. Cause it is one that is so much about perfecting physical movement.

So for example, For one level, you might have to go and, connect two things together within a certain time period. And so you'll go and record a robot catching,a component flying through the air that and then your spin physically in VR and you'll try and connect it to this other robot whose motion you've recorded.

And you're creating this whole sort of ballet of movement just from your own movement. I mean, it's not really putting everything else in there. Like you are creating everything there and it feels so fun and physical where you are kind of like crashing down on floor and spinning around trying to make this land, this connection that I was like, I've never played anything like this before.

You could not do this in any other kind of medium. You couldn't do this. It'd be too difficult to do. the controls would not really work in sort of a normal console game. It felt even [00:41:00] more physical and more satisfying than playing some. good game, like Beat Saber or some shooter game or things like that.

It felt something so unique to, to, to VR and I felt just really satisfied for it. I was like, wow. it's very rare that I come across like an entire new game mechanic where I was like, I could just keep playing this, honestly for another 10 hours. and they did a fantastic job of it.

So I really like that one. It's on the Quest, if you wanna try that out.

Amy: Wow. That sounds amazing. I really wanna try that.

So, I gotta ask, what are your thoughts on using AI in game production?

Adrian: I think a lot of people are using AI to assist their work in various kind of specific ways that could, as using it to sort of like answer questions and maybe writers using it to come over the interesting ideas or sort of brainstorm and so on. After using it, I think we're in the context of what we do.

often people will [00:42:00] say, oh, can you use, we'll, you use ai, will people use AI to write stories? And I think that is not really going to happen actually in the way that people think it will because the cost, the relative cost of coming up with a story is not actually massive compared to the overall cost of running the company.

And so, a less story is like really unimportant to your company. There's not really any point in saving the money to have a 90% as good a story or even a 95% as good a story if you can spend more money and get the hundred percent as good story. And so, a good example, be like, well, why should we pay Robert Downey Jr.

Like a hundred million to be Ironman, where we can get a Robert Downey? Look alike and pay him $0 and he's 95% is good. It's well just go and pay Robert Downey Jr. And then everyone will be happy, and you'll make even more money. [00:43:00] So from a kind of cost benefit calculation, I'm not really sure actually works, for certain applications.

But in a lot of games, a lot of media, actually 90% good is probably good enough. And so they will just go and use the AI solution. It is what happens to a lot of technology, it will replace a lot of things, but I'm not sure that will replace the very high end.

And that's where we aim to be.

Amy: Wow, fantastic. Thank you so much for joining us today. It's been an absolute pleasure to have you. Take care.