Good in Theory: A Political Philosophy Podcast

Good in Theory: A Political Philosophy Podcast

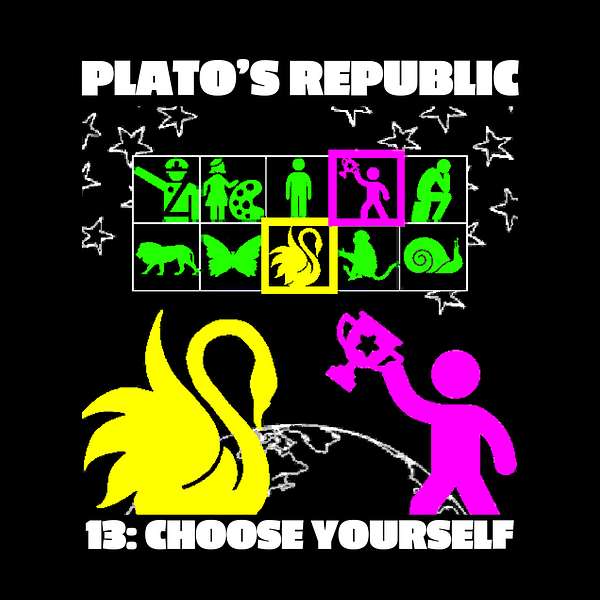

30 - Plato's Republic 13: Choose Yourself

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

This episode covers the last bit of book 10 of Plato’s Republic.

Imagine you get to choose your reincarnation. You can come back as a tyrant, a sports star, a swan, whatever you want. What do you pick? And what do you have to know to make a good choice?

Socrates has some advice. In this final episode of Republic, tell the story of a man who travelled to the afterlife and came back to tell the tale. This puts a didactic bow on the all-night conversation they’ve been having and demonstrates how Socrates thinks poetry should be written.

Credits:

Glaucon: Zachary Amzallag

Ancient music: Michael Levy

ntro theme: Clayton Tapp

Outro theme: David Zikovitz

Before we start today, I just want to mention that since this is the final episode of the 13, part Republic series, I've got a few announcements to make. I've put them at the end of the episode after the outro music, so please stick around and give those a listen. Today, the conclusion of Plato's Republic, a proof of the immortality of the soul, and the most important decision you'll ever make. I'm Clif Mark. And this is good in theory. Welcome to the end. This is the last episode in our series on the Republic. We'll still talk about Plato in the Republic and other episodes if guests come around. But this is the end of the dialogue. Thank you for sticking around. When I introduced the book, I compared it to a magic carpet ride. Because the argument picks up flies all over the place covers a ton of ground in all different kinds of subjects, without ever setting down and stopping to fortify one position. Since glaucon, and Socrates turned up Apollo Marcus's party and book one, they've demolished all the common ideas of justice. They've built imaginary cities, they've taken babies from their parents and turn them into superhuman philosopher kings, they climbed out of the dark cave of opinion using math and dialectic up to the sunny heights of the form of the good. And then they climb back down via regime change in daddy issues into the nightmarish mind of the tyrant, which, in the end, glaucon decided was not for him. And then, last episode, Socrates had a nice long rant against poetry, which took nearly to the end of the book as a whole. And all that's left today is a little bit of dialogue in which Socrates tries to convince clown con, that we have immortal souls, and then a pretty long monologue in which Socrates tells a poetic myth of his own, which wraps everything up by telling glaucon how to live his life. And we haven't even mentioned the greatest rewards of virtue,

Glaucon:what could be even greater than what we've already established?

Clif Mark:Do you think anything that happens in a single lifetime is great compared to all of time?

Glaucon:I guess not. But what do you mean?

Clif Mark:Haven't you ever noticed that our soul is immortal and never dies?

Glaucon:What? No, by Zeus, Socrates. I've never noticed anything like that. How can you

Clif Mark:say that? Think about it this way. Everything that exists, has its own particular evil, that makes it worse and destroys it. You've got rot for wood blight for grain disease for the entire body. Okay, I get it. And if this special evil can't destroy the thing, nothing can?

Glaucon:That seems likely.

Clif Mark:Well, what about the soul? Is there anything in particular, that harms the soul?

Glaucon:But of course, everything we were just saying, injustice, excess cowardice, bad education,

Unknown:and do any of these things destroy it?

Glaucon:What do you mean by destroy it,

Clif Mark:destroy it? make it disappear, like disease eventually does to the body? Well, no, of

Glaucon:course not. It would probably be better if injustice was fatal. At least if you're dead, you'd get some relief from the unjust life. But it doesn't work that way. And justice may kill others. But it makes the unjust person more alive and awake than ever.

Unknown:So if the souls own specific evil can't kill it, how could Anything else? Hmm,

Glaucon:I guess it can,

Clif Mark:then we have to conclude that the soul is immortal. But it's not exactly like the soul we've been talking about. Because we've been talking about the soul in life. And that has lots of parts. And it's all mixed up by its connection to the body. Looking at the soul in life, is like looking at the statue of glaucous in the sea. It's so worn away by the water and covered in shells and seaweed that looks more like a beast than a man. The immortal soul is different. It's pure, unchanging. Think of the part of the soul that loves wisdom, and the kinds of things that this part of the soul likes the divine in a mortal things. And now imagine if the soul gave itself completely to these things that it loves. That's like, pulling it out of the ocean and hammering off all the rocks and shells to reveal the true nature of the soul. But we've said enough about The souls like in life,

Glaucon:I agree on that one.

Clif Mark:Good. And since we agree that justice is best for the soul, even if we have the ring of God, geez, don't you think we should return everything that we took away at the beginning? How do you mean, at the start of the discussion, US me to take away the just man's reputation for justice, and all the rewards and benefits that he get for being just and to give them to the unjust man. And so now, just so we can see how valuable justice really is, let's put all the rewards and wages back where they belong.

Glaucon:Let's

Clif Mark:it would be unfair not to. Well, in that case, let's say that the just man will get all the prizes, he'll be the man most likely to rule in the city to marry whoever he wants, and to be successful and loved by the gods, and the unjust man, he's the one who will get caught in punished and humiliated.

Glaucon:Definitely, those are fair rewards for the just and the unjust man,

Clif Mark:but they're nothing compared to the ones that they get after death. You have to hear about these if each man is going to get what he deserves.

Glaucon:Vento, there's nothing I'd rather hear.

Clif Mark:Throughout the Republic, Socrates has been building this three part model of the soul that has reason, spirit, and appetite. But now he's telling you something slightly different. He's saying that the immortal soul is different from the soul he's been talking about. Because the soul in life is all mixed up with the body. And what he seems to mean by that, is that reason is obscured by its relationship with spirit and appetite. And if you scrape off those barnacles, you're left with Pure Reason. And that's the immortal part of the soul that travels to the afterlife in the story that Socrates is about to tell. Now, if you don't already believe that there are such things as immortal souls, then I have a feeling that the argument that he gave about would rot and green light didn't convince you. And if it didn't, don't worry too much about it. myths don't need airtight philosophical proofs to get off the ground, you just need an excuse to believe in them. So instead of focusing on whether or not immortal souls exist, try to focus on what Socrates is trying to get across when he's talking about them. The next bit of dialogue is actually a monologue and the conclusion of the entire Republic. Socrates tells a myth about a soldier named er, who travels to the afterlife, and then comes back to report on his experience. And before we jump into it, I want to give a little framework for interpreting the myth because it may seem odd that Socrates spent all of last episode complaining about poetic myths. And now he's going to close the whole show with one right before Socrates starts his story, he drops a clue about what he's up to. That's very easy to miss if you were not born and raised in ancient Greece. He says, I won't tell you a story of alcumus which is a reference to Homer's Odyssey. I'll canoes is a king that Odysseus visits and during his visit to that King, Odysseus tells a really long story about all his adventures, and it goes on for ages. So the term a story of Al canoes is an ancient Greek expression. That basically means a rambling, long winded tail. So Socrates is saying he's not going to do that. That's the surface meaning. But there's also more to it, because included in the long winded story that Odysseus tells, is a part where he talks about his journey to the underworld. So when Socrates says, I won't tell you a story of our canoes, he's setting us up to compare his story about the underworld to homers version. And so before we start, I want to tell you about Homer's version. It's intense, it's half horror movie and half tear jerker. Odysseus is on a mission to Hades to get some information, and he's surrounded by shuffling undead shades, and he's bribing them with blood from sacrificed animals. It is very spooky. It's also very emotional. The shade of a recently dead comrade begs Odysseus to go back to where he left his body and given a proper burial so he can finally rest. And Odysseus also meets the shade of his own mother, who tells him that she died of a broken heart, waiting for him to come home. And then when he tries to hug her, she just flits away because you can't hug a ghost. Odysseus then meets a bunch of heroes, and eventually he gets to meet the shade of Achilles. Achilles was the greatest soldier ever in The hero for all Greek boys. In Odysseus says, well, Achilles, I won't read for you because you were more blessed in life than anyone else. And now you rule over all the dead, so, death can't be too bad for you. But Achilles go says, don't you talk to me about death, I would rather live on Earth as the serf of a poor man, than be Lord over all the dead. So even the glorious Achilles is totally miserable down there. This story about Odysseus, his trip to the afterlife, is everything that bothers Socrates about poetry. It panders to the emotions, it makes the gods look mean, it makes death look scary. It shows decent people crying and lamenting, Socrates, his worry is that this kind of story will fire up the irrational emotional parts of your soul, and make it harder for you to be reasonable, in this case, will make you too scared of death to face it philosophically. In fact, Socrates has already centered out this particular story from Homer as something that needs to be censored back in Episode Four. Which is all to say that when Socrates says, I'm not going to tell you a story of our canoes, he means keep this Homer story in mind, because he's about to show us how poetry about the afterlife should be written. And you'll notice immediately that the Socratic version has a completely different vibe. History isn't scary or sad, it's chill in spacey. It feels less like he's putting you on a roller coaster, and more like he's giving you a puzzle to solve. There's a moral message in the story that requires a fair bit of interpretation and figuring out clues. And I'll talk about that after the myth. But Socrates also includes a ton of descriptive detail in the story. He describes the spindle of necessity, what's it made out of? How does it look, he puts in a lot of detail. He makes a point of saying how many days it takes for the souls to travel from spot to spot in the underworld. It makes all these little comments that I've mostly cut out because I don't really get them all and they would take forever to include. But all these little details have had Plato's readers trying to figure out what he meant for 1000s of years. I think of the difference between the two kinds of poetry this way. Homeric poetry is trying to wring out your heart Socratic poetry is trying to tease your brain. I'm not going to tell you a story of volcanus. Instead, I'll tell you the story of or was a pimp Chilean soldier who died in battle. And it took 12 days for his friends to finally recover his body and bring it home and get it onto a pyre for his funeral. And that was when Earl sat up in his own funeral pyre, came back to life, and told the story of his journey to the other world. Or said that when he died, his soul traveled with the whole crowd of others to a strange place. On the left, there were two openings in the ground, an entrance and an exit. And on the right, there were two openings in the heavens. And in between the two sides, there were judges. As each soul got to the front of the line, the judges attached a sign that said just on the front of the souls who live just lies, and he told them to go up to the heavenly entrance on the right. For the unjust souls, they pinned a sign with all their deeds on their back and sent them down into the earth. When irga to the front of the line, the judges told him not to take either path, but just to look around and take it all in so he could report back to humankind or didn't just see souls leaving on their journeys. He also saw them coming back. And as they arrived, they all gathered together on a big meadow, like a public festival. And they found their old acquaintances, and they told all about their experiences on their journey. The ones who arrived from the underground path were all dusty and parched. And they were crying and lamenting because they had just finished 1000 year journey underground, where they were punished tenfold for every unjust act that they committed in life. And the souls that came from the upper path were clean and fresh, and they'd spent 1000 years being rewarded with amazing experiences and sites of indescribable beauty. are heard some people asking about a famous tyrant from his own hometown that died 1000 years ago but someone said He wouldn't be coming to the meadow. Because when men had done so much evil, that even 1000 years of punishment couldn't fix their souls. They were dragged back down for more torture. And this was mostly tyrants. All the souls from both paths spent a week on the metal together. And then they traveled for four days until they could see a great column of light that supported the heavens. And after one more day of travel, they arrived at the spindle of necessity. The spindles world was like a giant hollow ball, with seven other balls nested inside, and all of them had different colors, and they were turning at different speeds, and the outer multiple was turning in the opposite direction. And on the lip of each bowl, set a siren singing a single note. So together all of them created a harmony and the fates of past present and future were also there singing to the sirens harmony in spinning the spindle. The feets had a spokesman who came to address the gathered souls, and it told them, you've arrived at the beginning of another cycle. And it's time to choose your next life. You'll get to choose your own life from the available options, but the order you choose in will be random. Remember, how virtuous you are in life depends on you. God is not to blame. And then this spokesman gave everyone or a lot with a number on it. And then lay down patterns of all kinds of different lives in the ground. And these included patterns for the lives of tyrants, rich men and women poor, beautiful, ugly, sick, healthy, every combination of qualities and life events were there. Even animal lives related to these patterns showed what would happen in the life. But they didn't show the arrangement of the soul, because that depends on the kind of life that the person chooses. And now here, my dear glaucon, is the whole risk for a human being. This is why we should forget about everything, except for studying how to tell good lives from bad, and finding people who can help us identify and choose the best life that we can. And to do that, we need to study how all the different factors in life, wealth, health, power, or the lack of these things, quick wits and good looks. We have to understand how all these things affect the soul. Because choosing a better life, a life that makes us all more just and is therefore happier. That's the most important choice we make in life and after death, are said that the next thing that the fates told the Souls was not to worry, because there were enough lives available, that even the person who picked last would be able to find a good one if he chose carefully. But they also warn the souls not to be careless, if they chose first, then this will lead to the first lot ran in immediately grabbed the biggest tyranny it could see. And then when it looked closer, he saw the life was filled with horrible things, even eating his own children. And he started crying and blaming the fates and the gods and anyone but himself. And Earth said that, oddly enough, this soul that pick the tyranny, he lived a virtuous life last time around, and he had just come down from 1000 year journey in heaven. But the thing is, he lived in a decent regime with good laws. So he was only virtuous, out of habit, not from philosophy. And actually, most of the souls who made that kind of careless mistake had come from heaven. Whereas the people who came from underground, they'd suffered, and that made them choose more carefully. So the majority of souls alternated between good and bad lives. But that doesn't always happen. Or said that if anyone practices philosophy consistently in their life, then chances are they'll be happy in life. And afterwards, are said that watching the souls pick their new lives filled him with wonder and laughter. Mostly, he said, they chose according to the habits of their previous lives, the soul of Orpheus. He was killed by a woman and so he didn't want to be born by one. So he chose the life of a swan. ajax chose the life of a lion. Agamemnon hated humankind, too. So he chose the life of an eagle in Atlanta took the life of a famous male athlete. The very last soul to pick was Odysseus. He remembered all the suffering of his life, and that had cured his love of honor. So he spent a long time looking through all the patterns of lives. Eventually, he found what he was looking for. It's a life that had been rejected by everyone else, but he said that even if he chose first he would have picked it. It was the life of a private citizen, who minds his own business. When all the souls had chosen lives, the fate spun them into irreversible threads. And the souls traveled together to the river of carelessness. And they drink a certain measure of water to make them forget what they'd seen, although some of them drink too much. Then, at midnight, there was a great earthquake in thunder, in all the souls were carried to their new births, like shooting stars. But they stopped her from drinking the water. And instead of traveling to a new life, he came back to his own body, and woke up on his funeral pyre. And that Lacan is how this story was saved, and how we can save us. If we believe it. If you ask me, we should all believe that the soul is immortal, and can deal with all kinds of goods and evils. And we should always take the high road MB just so we can carry off all the prizes in this life, and on our 1000 year journey. And that is the end of Plato's Republic. The last thing that Socrates wants to tell glaucon and the rest of the gang, is this myth that can save our souls if we believe it. But how, what does this myth do that Homeric myths don't? The first thing that happens to the souls is that the good ones get 1000 Year Award in the bad ones get 1000 year spanking. So maybe the story is just supposed to save us by motivating us to be just, and that is really intuitive. It's just what I think most people would expect, if they've lived on earth after 2000 years of Christianity. But the myth of Earth isn't a Christian hereafter, the punishment and reward, it's not eternal. And it's not even the important part. The important part is when the souls choose their new lives. And we know this is the important part because that's when Socrates steps out of the narrative indirectly tells glaucon the most important decision in life and in death is what life you choose. When it comes to the choice of lives. I'm only cloud con, I don't really believe in immortal souls. So I read the mythical choice of lives in the afterlife as a metaphor for the choices that we make in this life. I think Socrates is telling glaucon that the choices that he's making, especially now that he's a young man coming of age, he's saying that these choices are important, because they'll determine what kind of man he'll become, and how happy his life will be. And of course, the myth is pushing him towards choosing the just life and taking the high road and always being good, and telling him that ultimately, that's the happiest way to live. But that's not the only message here. Because it's not obvious how to be just right at the beginning of the Republic, we learned that being just isn't just a matter of following the rules, or helping your friends. The common ideas that people have of justice aren't enough to guide us. Socrates says that we have to learn how all the different factors in life can affect the soul. Being just requires wisdom. Reserve puts it, the only way to improve our chances of being happy in this life and in the next is to practice philosophy. So how do we do that? How do we learn all the stuff that Socrates says we need to know in order to choose a good life? Well, this is what I think the other big message of the myth of Arras. I think that this myth is about education. And actually, it's the third myth about education in Plato's Republic, in which the characters start underground, and then wake up to real life. The first one was the noble lie, also known as the myth of the metals. The kids in the ideal city, they started out with a musical in gymnastic education, that was supposed to subconsciously shaped their likes and their dislikes and their tastes. And then when they're grown up, the rulers tell them that actually, their whole childhood where they thought they were being educated, they were really asleep underground, being built by the gods who are mixing metal in their souls. This myth is about the education you get from subconscious influence in habituation, that just comes from living in a society. The second myth about education was the allegory of the cave. This was about formal education. People start out in the darkness just going by other people shadowy opinions, then they use math and dialectic to work through the contradictions of common opinion and climb out of the cave into the light and see things as they really are. The third myth is the myth of her. Again, the souls start in the underworld. They make their big choice and then they fly up like Shooting stars to their new lives. But before they do that, the myth of Earth shows two ways that souls might practice philosophy and become wise. The first is to learn from experience. And most people do not do this, or is laughing when he's watching the souls pick new lives, because of how bad they are at learning from experience. One very common way not to learn from your experience is just never to think about it and to follow your appetites. This is what happens to the first soul that picks the big tyranny where he winds up eating his kids. And I think the lesson here is that if you think you're a good person, because you generally just follow the rules and don't get into trouble, you should be careful, because decent societies with good laws can kind of just keep everyone on side automatically. You can go along with the rules, and never have to think about why the rules are there, or why you really should be just a virtuous. The problem here, according to Socrates, is that if those social guardrails are ever taken away, this kind of unreflective person is in danger of driving right off the cliff. Another way of not learning from experience is just to follow the habits you've developed or to react emotionally to your experience. There's a whole series of characters in the myth that do this. Orpheus was killed by a woman, he winds up hating women, so he chooses to be born a swan. at Atlanta, the female athlete chooses the life of the male athlete, and so on. None of these people are really stepping back and thinking about what's good for their soul. They're just reacting to a happy or painful experience in their past. This is really common. I know that I make decisions this way. And I'm pretty sure that making this podcast was this kind of decision. The last guy to pick is Odysseus. And he's the one who shows how to learn from experience. It's not easy. Odysseus, his life was full of suffering and sorrows. And he was not a very just person. But all that suffering cured him of the love of honor that got them into so much trouble in the first place. And it made him think really hard about what kind of life he choose next. So it seems like the key to practicing philosophy on your own experience, is to try to let go of the irrational passions that tend to motivate you to step away from your habits and your trauma, and to reflect on what would really be best for you. And I like this bit because Odysseus, his story also implies that you're more likely to learn and become wise from a really varied and not entirely by the book kind of life than you would from being a perfect rule following goody goody all the time. The other way that the myths shows us that we can practice philosophy is by learning from each other. After the 1000 year journey of punishment or reward, all the souls get together on a big meadow. And they can see what happened to everyone. The ones who've suffered are dusty and worn, and they have a big sign of all the bad things they did pinned to their back. And the ones who've lived justly are clean and fresh. And they all get together and they talk and they swap stories. And then they traveled together to the spindle. This is what they're doing before they choose a new life. And this is the kind of philosophizing that Socrates practice in his life. He would just walk around Athens, looking for people he could learn from, and then he would question them about their lives in the condition of their souls. And so I think the myth is recommending this as a way to learn how to distinguish good lives. from that. I said that the myth of Earth is like the myth of metals in the myth of the cave, because they're all about education. But there's also an important difference. The other two myths are about how education should work in the ideal city and speech. This is where philosopher kings learn their philosophy through perfectly designed musical and dialectical education programs. And that means it's too late for glaucon and Adam antas, or anyone else who grew up in Athens, or anywhere else, for that matter. But the myth of her is different. It shows us a kind of philosophical education that is available in an imperfect world, and especially in a democracy. For one, the real world makes a much better school of hard knocks than Socrates is utopia. Odysseus had to go through a decade of war, and a decade of being chased around the Mediterranean by Poseidon before he got wise. And you just don't get those kinds of experiences if you're being raised as a philosopher King. And even though Socrates throughout the whole book is really hard on democracy, for all the ways that fall short of the city, and speed Democracy is still the absolute best environment to do Socrates this style of philosophy. And that's because democracies are diverse. They're full of different kinds of people with different experiences that you can learn from the agora in Athens is kind of like the big Meadow in the afterlife in the myth of her. Compare that to how it might be in the city in speech, because I just can't imagine that a bunch of soldier mathematicians were brainwashed since the day they were born, would make great chat. So it kind of fits to me that Socrates closes the republic with this myth. Because when the party Apollo Marcus's is over glaucon and Socrates and Adam, mantas and the whole gang are going to go back up to Athens, and so are Plato's readers when they're done with the book. And the final message that Socrates leaves us with is an exhortation to philosophy, not the kind of philosophy that you need 20 years of geometry lessons just to get started in the kind that glaucon and the others can practice on the walk home. And that you can practice with anyone who's willing to talk to you. That's it. We Republic is done. Thank you to everybody that helped. Thank you, Seth, who did all the episode art and read the scripts and listen to my drafts in my constant complaining, you're the best. Thank you, Maria for the pot art. Thank you, Zack and Rebecca amsel egg for playing glaucon and Adam Mantis. And thanks to Paul Sager and Elliot chambers and Andy Fleming for other voices. David zyk, evitts and clay tap, give me the theme music. And thank you Michael levy for the classic Greek background music. Everyone else who helped out with editing, giving feedback, listening to drafts just encouraging me. Thank you. And thank you for listening. I know it's been a long one, I hope you got something out of it. And if you did, if this podcast helped clarify playdough for you, or especially if you're a teacher, and you use it as a teaching aid, please consider supporting us on Patreon. That means you go on the patreon.com website, find good in theory, and pledge to support a couple of dollars per month. The podcast is entirely supported by listener donations. So every little bit would be appreciated. Now that Plato's Republic is done with her good in theory, for the next couple of months, I will be publishing a little bit less. But I will be coming out with a few really interesting interviews and other thought lab with Paul cigar, and a couple of small playdough related things I still want to throw in. But I'm also going to take some time to do some research for my next multi part series which should be on the concept of meritocracy. And possibly one after that on Hobbes is Leviathan. In the meantime, if you have any questions about political theory, or playdough, or requests for future episodes, or just want to reach out, the contact information is on the website at good in theory pod COMM And I would be really happy to hear from you