Act One Podcast

Act One Podcast

Screenwriter Paul Guyot

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

Act One Podcast - Episode 33 - Interview with Screenwriter, Paul Guyot.

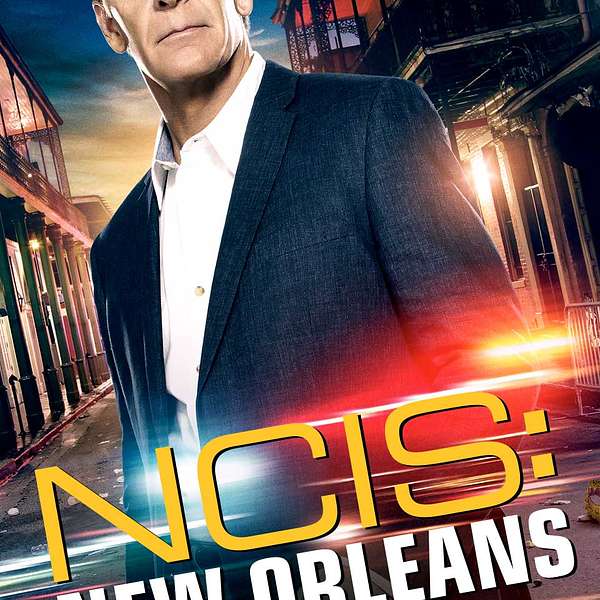

PAUL GUYOT has written and produced more than 200 hours of television. His work includes the JJ Abrams created FELICITY, the Emmy-winning JUDGING AMY, and LEVERAGE for TNT which won back-to-back People’s Choice Awards. Guyot served as Co-Executive Producer on THE LIBRARIANS, including taking over all showrunning duties for Season Two. After that he served as the Co-Executive Producer for NCIS: NEW ORLEANS -- at the time the 8th most watched series in the world. He has written pilots for multiple networks and studios including his original pitch THE BLACK 22s -- based on the true story of the first all African-American squad of detectives in St. Louis, MO -- which sold in a fierce bidding war between four networks. The series died in development hell, but Guyot retains all rights to the story and is currently developing a feature film with award-winning screenwriter Geoffrey Thorne.

Guyot co-wrote the Warner Brothers feature GEOSTORM starring Gerard Butler and Andy Garcia, which grossed more than a quarter billion dollars worldwide. But don’t hold it against him. His spec feature TIME BANDITS was optioned by Slated and is presently out to some of the top directors in Hollywood. Currently, Guyot is developing COLONIE 07 for French television, one of the first American screenwriters ever hired to do so. He is the author of several award-winning short stories, and his bestselling DARE TO LIVE -- a serialized story on Amazon’s Kindle Vella platform -- was chosen as a Top 200 favorite out of more than 17,000 stories.

In May of 2022 Guyot launched http://screenwritingtruth.com -- a website dedicated to helping emerging writers learn the truth about Hollywood and a career in screenwriting.

Guyot attended the University of Arizona. In his non-writing time he enjoys cycling, golf, mechanical watches, and his quest to find the perfect old fashioned.

The Act One Podcast provides insight and inspiration on the business and craft of Hollywood from a Christian perspective.

The reason I am so proud to be a screenwriter and so blessed is because the entire industry of Hollywood does not exist without us. We are the only entity in the entire industry that creates from nothing. Everyone else interprets what we create. The actor, the director, the DP, the costume designers, the music, the editors, everyone interprets what the writer creates. They may change it, they may elevate it, they may ruin it, but nobody creates from nothing except us.

SPEAKER_00:This is the Act One Podcast. I'm your host, James Duke. Thanks for listening. Please don't forget to subscribe to the podcast and leave us a good review. My guest today is screenwriter Paul Guill. Paul has written and produced more than 200 hours of television. His work includes the J.J. Abrams Creative Felicity, the Emmy winning Judging Amy, and Leverage for TNT, which won back-to-back People's Choice Awards. Paul served as co-executive producer on The Librarians, including taking over all showrunning duties for season two. After that, he served as the co-executive producer for NCIS New Orleans, at the time the eighth most watched series in the world. I did not know that. Paul also co-wrote the Warner Brothers feature film Geostorm, starring Gerard Butler and Andy Garcia, which grossed more than a quarter billion dollars worldwide. Just wait till you hear him tell that story. In May of 2022, Gio launched ScreenwritingTruth.com, a website dedicated to helping emerging writers learn the truth about Hollywood and screenwriting. Paul is a good friend, and if you are like me, I think you will find his honesty and thoughtfulness refreshing. Enjoy. Paul Gio, welcome to the Act One podcast. I am happy to be here, James Duke. This is fun to uh finally have you on the podcast. You we were just talking. You uh we originally connected through the podcast, right?

SPEAKER_02:Yeah, that's right. I had stumbled across the podcast because I was literally searching for anything the least bit Christian that had to do with the film industry, and I heard your podcast and it blew me away. And so I had to send you like a fanboy email.

SPEAKER_00:You you're our you're our one and only fan. Thank you. That's right. My one and only I'm not a t-shirt made of. This is uh Paul Paul listens to my podcast. Right. Um, Paul, it's great to have you uh on. It's a real honor and privilege to have you on. We've since built a a lovely relationship. I I admire your work. You you've been you've worked in the industry for um quite a few years, written for a lot of television as well as then let written a lot of film. And that's kind of what I wanted to talk about today. I just wanted to sp let people just get to know you and just hear your story, hear your journey. Because I think there's a lot of uh little gems and kind of gold nuggets people can pull out to just kind of learn for their own process, and which is why, by the way, um I invited you to participate in the Act One program as a mentor and um and uh and even faculty. So that's been a lot of fun having you as well. The the response having you as a mentor uh from our students has been um has been off the charts. You they they have really enjoyed um you so thank you for that, by the way.

SPEAKER_02:Oh well, thank you. It is a pleasure and it's a true honor. I I love giving back, and especially in a in a faith-based arena like Act One, it's so rewarding. I I love it. I hope you'll have me as long as you'll have me. I'll I'll always do it.

SPEAKER_00:Well, let's let's jump um, let's go back uh a little bit. I'd love for people just to kind of get to know Paul Gio. Tell us a little bit where where are you where are you from originally? Are you originally uh California native? Arizona, born born and raised in uh like the Phoenix, Scottsdale area. And the the journey to becoming a professional screenwriter, did that start early in your life? Did it did that was that a a passion to write? Was that something early, or is that something that kind of developed over time?

SPEAKER_02:It's an interesting question because it was I certainly had the the storyteller in me. I mean, as early as fifth grade, however old you are then, I was I was writing stories about my fellow classmates to make them laugh and and you know, printing up my own little books with you know construction paper as the covers. And but I didn't know, literally didn't know that you could write for a living until a guidance counselor in high school said, You should probably pursue this writing thing. And I had no idea it was even a thing. And I went to college then, I went to University of Arizona as a creative writing major. And even though I had I had always just loved television and and movies, that was that was my thing. Um, again, I didn't know screenwriting was a thing until I got into college, and it wasn't even my teachers, uh, it was a fellow classmate. And you know, he wanted to act and I wanted to write, and we both wanted to direct, and we kind of connected and and you know, after college, headed out to Hollywood with our with our screenplays that were literally written in spiral notebooks. That's how much we knew.

SPEAKER_00:Nice, nice. Do you uh remember when you first learned how to uh format a screenplay? Was that like a in your mind like a real challenge to write it? Or did you, or by the time you were formatting, were you writing on a on a computer?

SPEAKER_02:Well, no, what's interesting about that question is, and this is what I tell people like you you don't have to spend money to learn formatting. I mean, even though I was writing in a spiral notebook, my format was pretty good because I was just copying screenplays. You know, I I went to the library or you know, wherever the film department and found screenplays and copied the format. Um, so I was doing it, I was just doing it by hand with a ballpoint pen, uh, which I didn't know is kind of frowned upon in the industry. Um, so yeah, so by the time I got my first computer, you know, some Toshiba laptop, whatever it was, um, then I was using, I think it was Word Perfect.

SPEAKER_00:That's how long it was WordPerfect, yes. Shout out to Word Perfect. Tad, pad, pad, pad, pad. Exactly. What uh the uh I know all these these kids today, we're gonna snipe a bunch of old uh the the old Muppets, the old guys on the Muppets. These kids today with their with their formatting software, they have no idea, right? Um the uh I think Tarantino doesn't Tarantino still claim to to write things by hand.

SPEAKER_02:Um I think he yeah, I think his process is he writes everything out by hand, and then now he has you know people that will transcribe it or whatever for him. But yeah, I think he still uses the big long legal pads. Yeah, I think so.

SPEAKER_00:I think so. Um, so uh I'll I'll just pause there a little bit on on the reading the scripts and kind of learning just through going to the library and getting scripts. Do you remember some of the early scripts you read, the ones that you loved? Or are there scripts in particular that you think back? Man, that was such a great script. Things that got scripts that got you excited, scripts that that really kind of turned you on to uh screenwriting?

SPEAKER_02:Yes, actually. Um, because as I said, when I was in college, it was creative writing and it wasn't the best experience for me. The the professors I had were very much that sort of frustrated novelist, and so the classes were always this is why Faulkner stinks, you know, and you know, they have their unsold manuscript in the drawer. Yeah, yeah. Um, so when I got to LA, like I had found stuff at my university library, you know, I had said some screenplays, and I honestly don't remember what they were, but what was a huge epiphenal moment for me is when we got to LA, and I was, you know, I'm just a kid at this point. I'm I'm barely 21 or whatever it was, and I discovered the WGA and that you could go into their library even without being a member. Yep. And I remember reading Alvy Sargent's Ordinary People and just thinking, I'll never be that good. I remember the the one that most affected me, though, is funny and started me on my journey. I used to be a very avid collector of screenplays back when they were all hard copy and you know the names were written on the spine in black sharpie. Yes, I I collected hundreds of screenplays, and the first one I remember reading that really just I remember thinking, I can still see myself sitting there going, This is what I want to do. And it was Shane Black's lethal weapon script. It's a great script. Wow, and that's a high bar. That's a high bar. Well, that was, and that's the first time I think I ever realized what you know now that I preach so hard is voice and originality. That that screenplay didn't look or read like anything else I had seen before, and it was just so evisceral. Uh I I just I just I still remember that moment. And then that led me to like William Goldman and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, which is amazing. And those those scripts were really the ones that that just changed something in me.

SPEAKER_00:Why? Can we let's just talk a little bit about this? What what maybe let's focus on the lethal weapons script? Because I think there might be some people that listen to this and go, what lethal weapons script? Oh what was it about that script and what what is it about those types of screenplays that we can learn from as screenwriters to when we read them and and in a sense study them?

SPEAKER_02:I think uh it's it's what I said when when you talk about voice, like it's it's funny. I just just put up a post recently on my website about this that you know, up until Goldman, William Goldman hit the town, voice wasn't a thing. The screenwriter's voice wasn't a thing. You know, Jack Warner called them schmucks with underwoods. And every, you know, the only way that their individual voice ever came out was maybe in the characters' dialogue, but that was it. And then Goldman showed up, who'd never written a screenplay, wasn't under contract with anyone, and just wrote what he thought he wanted to see. And it didn't sound like anything the town had ever read or looked like anything they had seen. And that I believe led to the next 30, 40 years where the screenwriter's individual voice became everything. You know, when you have Shane Black and Alvin Sargent and Jay Presson Allen and Joe Estherhaus and you know Nora Efron and all these people coming out that that became huge successes because they wrote in their own voice. And what what that means is like when you go back to the Lethal Weapons script, you know, it's the I had seen the movie and I thought the movie was just fantastic. You know, I loved every minute of the movie. But until you really get into this, you know, as a kid back then too, you just think like, wow, that's Mel Gibson, being Mel Gibson, and you know, Richard Donner's amazing directing. And um, and then you see it on the page. And and even though, like I had said, I remember reading ordinary people and be emotionally moved by that screenplay, Lethal Weapon was the first time I I remember realizing that that the writer that Shane Black actually created those characters, and and actually that you know, Martin Riggs, it wasn't Mel Gibson, it was Shane Black who created, you know, and Mel Gibson then interpreted what Shane had created. And and the other thing about that script that I remember is it was written with so much confidence, almost bordering on arrogance. Like, you know, if you've read it, he talks to the reader. You know, there's there's a line he says he makes there's some action or description line, and he says, something, something, but wait, dear reader, you know, he and and you're just sucked in almost like it's almost like a comic book. And that opened my eyes that oh, I don't have to follow these these rules, I don't have to color inside the lines. I can just put myself on the page, and and that works, you know, and that's what really has stuck with me my whole career, even though I didn't start doing that till years later. You know, you start out, I think, at least for me, and I think a lot of other writers, I started my process because I had never tried writing any sort of screenplay or script um until, like I said, I was planning on moving to LA. And my first, you know, couple of years at least, if not more, of writing, I was doing bad fan fiction of writers that I admired. You know, I was writing bad Shane Black and bad Scott Rosenberg and you know, stuff like that, because I didn't know what my voice was yet. I had to find it.

SPEAKER_00:Well, how did you find your voice? Did it just require the work and the effort of just just writing and rewriting and rewriting and rewriting? Uh, I'm curious when you thought and realized, oh, this is me on the page now. I I've suddenly I've transitioned from writing bad fan fiction in your own words, to now I'm this is this is this is Paul Gio. This is this is this is how I write screenplays.

SPEAKER_02:Yeah, it's a great question. And I think it only comes through the experience of writing and writing and writing, because at first you don't know you're writing fan fiction, you know. You you think you're like, look how clever I am. I sound just like Shane Black. Well, that that doesn't mean you're clever, that means you're, you know, a mimic. And it's just through eventually that and other people giving you notes, like getting feedback and stuff, and saying, you know, this sounds like bad Shane Black or bad Scott Rosenberg, you know, and then the more you write, I I believe you just start to find yourself because every every time you write something, and the next thing you write, you're a better writer. And even if you write something that's complete garbage, the next thing you write will be a little less garbagey, if to make up a word. And I I just think eventually I gained confidence in just trusting myself. I knew that I was a fan of their style of writing and the style, the type of stories they told, and the tone of their stories. And so once I quit focusing on trying to be as cool as them and just write my own story, it was just a process of elimination almost. You know, one script would have a little less Shane Black in it, and the next script would have a little less until eventually it was my own voice. And and I can't remember if I told you this, Jimmy, or not, but I there was a point um in my career, I spent several years when I first got to Hollywood working as a stand-in before I ever became a paid writer. And I was trying to write, and I was really at the point of giving up. I was really ready to think I just don't have it, you know. And I had written one last thing. And again, it was this was during the 90s now, and Tarantino had exploded, and everybody was doing all the derivative Tarantino stuff. And I had written this one screenplay that was kind of, I'd say, Tarantino-esque in its story, but not in its tone or anything. And I thought it was pretty good. I thought this might be the best thing I've ever written. And I gave it to somebody who happened to be an assistant at the Kennedy Marshall Company, and of course, they didn't do movies, anything like that. But she offered to have it covered because back then, you know, that was the big thing. They had the readers, and you got the official coverage, and that was like a price thing. Wow, if you could get real coverage from a company like that, you'd you'd collect coverage, you'd you'd collect coverage and yeah, and show it to people. Yeah, yeah. And so this they covered my script. And of course, you know, it was just some reader, and who knows? This could have been some, you know, buddy working at a coffee shop or something. Um, all you have to be a reader is the ability to read. But so they passed on the script, obviously. The the coverage came back and it was a pass, and it was uh, you know, two pages and a page and three quarters of everything that was wrong with the script. And then the last block, the last paragraph, the the reader said is that said, comma, I do believe this writer is on to something. There's a rawness in here that looks like you know, there's talent on the horizon or something if they just keep working at it. And that right there was all I needed because to me, you know, it took me years to realize that was just some reader, but to me, it was the Kennedy Marshall Company telling me I've got talent, I'm on to something, and that kept me going.

SPEAKER_00:I love that. I love that story, and and the that kind of outside affirmation that we need to just let us know that we're headed in the right direction. We're not there yet, but we're headed in the right direction. You know, at Act One, we teach our screenwriting students, I tell them, I tell them all the time that every writer has a thousand bad pages in them. And the sooner we can get you writing, the sooner we can get those pages out of you so we can get to the good pages. And what I hear you saying is um the best way to break through for you, and the best way someone else is gonna break through is to write and to just keep writing. And you're going to experience what you said right there. You're gonna experience disappointment, you're gonna experience frustration because no writer sets out to write something and then writes the end and thinks what they've written is absolutely abysmal. They they they have you have that hope whenever you whenever you type the end that man, this could be the thing that right. But then over time you learn how many, how many of us writers look back and go, oh man, that stuff I wrote early on. I would never want to see the light of day. But back then you thought it was the best you'd ever done. And but how do you know if you don't just keep writing? There really is no um quick fix to this, is there, Paul? Like you can't short circuit this process. Writing takes becoming becoming a writer takes time, it takes the time it takes to write.

SPEAKER_02:Yes, that's that's the thing. And I I feel like one of the problems today, and I think it's societal to a certain extent, because of the immediate gratification of technology in our lives and and you know, the dopamine of social media and all that. And and I feel like I run into so many people today that they they want to sell something as opposed to wanting wanting a career as a writer. You know, if you want to be a screenwriter, if you want to have the life of a writer, you've you've it's a marathon, not a sprint, and you've got to put the work in and you've got to play the long game, you know. And and so many people I run. Into and they've they've written one thing, or they've written, you know, six five-minute episodes of their web series, and they they want the keys to the Malibu Beach House. And it's like, well, that's that's not gonna happen, I don't think. You know, everybody has the lottery ticket stories, you know, every one in 10 million times something crazy happens, but the odds are against you. But if you keep your head down, you put the work in, every time you write, you get better. The more you read, the better you get. And if if you just commit to the journey and not the destination, I think you know, Andre de Shields, uh that amazing actor who won a Tony a few years back at age 78 in his acceptance speech said, slowly is the fastest way to get where you want to be. And and I believe it with all my heart.

SPEAKER_00:That's a great quote. Oh I the you know the one exception I've heard of, and I and I I kind of I kind of don't believe them. Is Angelo Pizzo, who wrote Hoosiers and Rudy, claims that Hoosiers was his first script that he only did like one draft on, I think.

SPEAKER_02:I just like I'm like that's just that's a little I mean, I'm not saying it's not, I'm not calling him a liar, but I kind of no, I'm just well, you know what's it's funny though, because I have a friend named Brian Coppelman, and he he has a writing partner, David Levine, and they've written a bunch of movies, you know, and they've had they've did billions on Showtime, and they've got another series on. And Brian loves to tell people, he was in the music business before he and David became writers, and he loves to tell people rounders is the first script I ever wrote, first script I ever wrote. And while technically, yes, it's the first script he and David wrote together. Both of them had been writing other things separately for years. You know, I mean, David Levine had been writing unpublished novels and short story collections, and and Coppelman had been writing short story after short story and essays and all types of things. So, yeah, technically, first script I ever wrote, but they'd been honing their craft for years.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah. I always say the exceptions only prove the rule because it just that is it's there's always lightning in a bottle that can get caught once in a while, but um that's not the that's not the goal. The goal is to become a great writer, and you can't short you can't short circuit that. Um the uh so let's go get a little bit back to your to your story. So you're here in LA, you oh let's jump ahead to that. You you you were writing, you were getting frustrated, you were doing um, you were doing extra work, things like that. Um, what was your first um official professional credit? What was your first paid gig as a writer?

SPEAKER_02:So my very first pay, it's funny, it happened all within a matter of weeks with each other. I I got called in for a show called Snoops, which was you know 13 and out. It was a David Kelly E peach show, and I got called in to pitch ideas for a freelance episode. And I got the gig. I went in and I pitched some ideas and I got hired to do a freelance. So that was my first official you're going to be paid for your work. They they had read an NYPD blue spec that I had written, and that's how I got the meeting off of that. And before I had even gone to script on that, I was in the outline phase, and I got called to go meet JJ Abrams and Matt Reeves for Felicity. Um, because season two was was gonna had just been announced something, and so they were looking. So I still hadn't turned in my my draft of Snoops, and I went to meet JJ and Matt, and that was really crazy because um they hired me right there in the room. I I talked to them for about half an hour, it was very surreal. It was at the hotel Mondrian, and JJ goes, Okay, can you uh go down to Baldwin Hills right now? Uh the writers are meeting and help them break story. And I and I was like, I don't know what break story means, but uh, but I just go, sure. And uh so I get in my car and I said you said you said where's Baldwin Hills? That's what you yeah, oh yeah. I had you know we didn't we didn't have Google Maps, and so I had the Thomas guy out there. Yeah, you had your Thomas guy out, yeah. And I'm driving down there and I call my agent, and he didn't even know. And he was more excited than I was. That I had a very junior agent at the time at Gersh. And so I go down there, and anyways, I I do that job, and then in the following week, or I think over that weekend, like I just killed myself to turn in the Snoops freelance. So technically, Snoops was my first paid gig, but then within that same week, I or two weeks probably I got the staff gig on Felicity. Wow.

SPEAKER_00:And at the time, did you prefer, like, were you looking at writing television as that's kind of where I want to go? Or was it like, hey man, it's a job as a writer? Like, did did you ever have that weird dichotomy that some writers have in their mind where it's like, I want to be a feature film writer, I don't really want to be television, or I want to be television, I don't really want to do feature film.

SPEAKER_02:Yeah, I had I had come out, I think like most everybody, or at least most everybody back then for sure, I wanted to write movies. I wanted to be a feature writer. And as I said, I spent a lot of years when I first got to Hollywood as a stand-in on features. And it was through meeting people in that world and talking to them, talking to directors and writers and actors, and almost all of them telling me, you want to be a writer, get into television, you know, because that was back at the in the day where you know the writing, the writer of the feature wasn't even invited to the premiere. You know, we had to have that put into the MBA like in 2007 or something. That's that's how recent it was that we weren't even invited to the premiere of the movie we wrote. And so I started writing television specs um back then before you know, that was nobody wanted to read original stuff like they do now. And it was because the people in the feature world, the feature writers that would talk to me, and and I became friends, still friends to the state of Walter with Walter Hill, a great director, feature director, and writer, and a couple of actors, and they all said, No, Paul, the money's in television, the the writer is king and queen in television. So I was very blessed to learn that early on, and I started writing television specs, strictly, you know, Machiavelli. Like I was like, Well, that's how I can get in and make money. Okay, I'll I'll go television. And then once I got in, I realized I kind of fell in love with the you know, the world of TV and and how you can write a feature and sell it, and it could be two, three, four years before it ever comes to fruition if it does it all. Whereas, you know, you're working on staff of a television series, you're shooting an episode every seven, eight days, and it's on the air four weeks later, you know.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, that is something that I think is a lot of that's very gratifying for a lot of writers is that sense of you get to see what you what you've written um uh you know on on the screen so much so much faster, and you get to participate uh more. The writer gets to participate a lot more um in the process than like you said. I could do I could do a lot of podcasts from writers talking about the frustrations uh you guys have with how you're treated oftentimes on film sets. It's a it's a it's a weird thing in our business, isn't it, Paul? I don't know what it is. Yeah, maybe you have a theory on it, I don't know, but there is this um real lack of value or understanding what the writer does and therefore who they are. And I don't know if it's an insecurity or what, but having a writer on set intimidates a lot of filmmakers, doesn't it?

SPEAKER_02:It does, it does, and I I think it's born out of the schmucks with underwood thing from back in the day where they were just looked at as you know, take dictation. And then I think it was really that lie was perpetuated by Hollywood being such a director, you know, run medium, and people like you know, I mean, I I remember hearing Tom Cruise 20 years ago publicly saying stuff like, you know, a screenplay is just a blueprint, and we're all the filmmakers, and we're all the creators and the artists, and and that really stuck with people, you know, it's it's just if you hear Tom Cruise say it, it must be true. And I, you know, what I always try to tell writers that run into that is the reason I am so proud to be a screenwriter and so blessed is because the entire industry of Hollywood does not exist without us. We are the only entity in the entire industry, Jimmy, that creates from nothing. Everyone else interprets what we create: the actor, the director, the DP, the costume designers, the music, the editors, everyone interprets what the writer creates. They may change it, they may elevate it, they may ruin it, but nobody creates from nothing except us. And let's see how many movies or TV series are ever made without scripts.

unknown:Yep.

SPEAKER_02:I I just that's why I'm so proud to be a writer and a and a proud WGA member. And I think I don't want screenwriters to ever feel anything less than you know, being incredibly proud that that we are the driving engine of this giant behemoth of a machine.

SPEAKER_00:I think um I'm trying to remember, I think it was Quentin Peoples. I did an interview with him a while back. I don't know if you heard it, but seeing how you're my one fan of the podcast, but uh I he said he talked to Sir David Lean, he had the opportunity to meet Sir David Lean once, and he told the story that um he got to ask him a question. He was like, I can't let Sir David Lean leave without asking him a question. And he asked him, you know, what he would do differently or something like that. And Sir David Lean told him that if he were starting today at that time, he would he would be a writer, he would he would want to be a writer because because that's where it all begins.

SPEAKER_02:Yeah, and and certain there are certainly certain actors and directors that uh have that respect, and that you know, I when I was a stand-in, Don Johnson was somebody I stood in for for a few movies, and I was so blessed to he did a film okay.

SPEAKER_00:I gotta hang on a second. I gotta that was a little bit of a humble brag there. You you weren't standing in for Danny DeVito or that you're standing in for Don Johnson. Okay, I just want to point that out. All right, yeah, but it's it's Don Johnson, it's not like it's George Clooney. Still, I mean, Don Johnson in the 1980s, boy, you know.

SPEAKER_02:So, but we but he went to Toronto to do this movie called Guilty of Sin that was being directed by Sidney Lamette. And I got to spend 12, 14 weeks with Sidney Lamette, and including you got to spend that much time with him. Wow, I mean, the whole shoot of the movie, yeah, but but one of the great things of that is Sydney is so generous, he was so loving and giving. And there was a holiday weekend during filming, and Sydney invited myself and and his assistant and his first AD to go to Niagara Falls and just be the do the tourist thing, you know? And that was a master classes, masterclass for me as a young kid, wanting to be a writer and sucking up everything. And Sydney, I mean, his making movies book is one that I recommend to every screenwriter should read it. And that that man, what he knew about story and character and specifically how to tell it for the screen, as opposed to you know, prose or something, it was just amazing. And that's somebody he came out of the theater, so he had all this respect and admiration for the written word and for writers, you know, and he was a writer himself too. But he he just hammered into me then it all starts with the script, you know. He's like, I can certainly ruin a good script. He goes, but I I can't make a good movie from a bad script.

SPEAKER_00:I love it. That yeah, making movies and adventures in the screen trade are the two books that if I if I had to force people to read them uh before working in this business, it would be those two, those two books. They're they're they're that important, they're that essential. Um, I think. So let's uh let's talk a little bit about some of your writing career. You you were you you're on a couple of shows. You were you were also on um there was a big hit show on CBS back then called Judging Amy, yeah. Um that you were on for for uh quite a bit. And what was that experience like? You had the legendary Tyne Daily, she like won won a bunch of Emmys for that for that role, and you were working with the great Barbara Hall and Karen Hall, who are who are act um act one royalty. Um uh what was that experience like on that show?

SPEAKER_02:That was uh fantastic. That was one of the greatest blessings of my career to do three seasons on that and learn from from Barbara Hall and Hart Hansen, and of course, our our dear beloved friend Karen Hall. Um it was one of the I I've always said bar Barbara Hall and John Rogers are by far the two best showrunners I've ever worked with. And both of them, even though they're completely different people, they write completely different things, they share this common thing where both of them, especially Barbara, is so secure in herself that she encouraged the voice, the individual voice of the writer to come through on the show. So, you know, a lot of people think like, well, if you're writing on a show, it's all the same voice, you know. If and and sometimes it's true. If you're on Matt Weiner, every episode's gonna sound like Matt Weiner wrote it. You know, every episode of a Sorkin Run show is gonna sound like Aaron Sorkin run it ran it, and so on and so on. But what Barbara Hall taught me that was so amazing to see how she did it, is she encouraged our own individual voices to come through in the episode. So you could watch Judging Amy, and while every episode was certainly a judging Amy episode and sounded like you know, the show did every week, you could tell, oh, this is a Barbara Hall episode, oh, this is uh a Hart Hansen episode, this is a Paul Gill episode, oh, this is definitely a Karen Hall episode, you know, because the the writer's individual voice was allowed to come through, you know, whereas some showrunners are so insecure, they're gonna rewrite everything to make it sound like them, as opposed to making it sound like the show. And and that to me just comes from a place of self-assurance and security, you know, and John Rogers did the same thing on leverage, and um and it was those three years on judging Amy was the was the best thing for ever me, ever for me, because I was the youngest, most inexperienced writer on staff by far. So I not only, you know, the Hall Sisters who are amazing, and you know, how many Emmy nominations, Lord knows, Hart Hansen, who had just come from Canada, who was a major, major um force in Canada. We had Joe Doherty, who was an Emmy winning writer. We had uh Carol Barbie and Lila Oliver, like it was a murderous row of of a writing staff, and then there was me. So I was just sucking up knowledge every single day I went into that to that job.

SPEAKER_00:Compare it was did JJ run the room for Felicity? Who ran the room for Felicity? I'm still wondering.

SPEAKER_02:Um okay, what do you what do you mean by that? Like, let's what does that mean? So Felicity was was not the greatest experience for me. It was uh it was very, very dysfunctional. When I got there, the reason JJ was so desperate to get somebody hired and told me go down, start right away. There were only three other writers on the staff at that time. And JJ wasn't around because he had just signed his first huge deal with Disney then, and he was developing alias. And so the writer's room were these three people that one was a supervising producer, and two others were co-producers, and then there was me. And they had been on the first season of judging or excuse me, of felicity, and none of them knew how to run a room, and for whatever reason, to this day I don't know, but they all three just resented JJ and could not stand him. And there was so much just vile negativity thrown around, you know. That that when I talk about going down to Baldwin Hills that first day, this is what happened to me. This is I go down, this is my first day on a show that's a big giant hit. You know, Carrie Russell had just won the Golden Globe. Everybody was talking about Felicity, I put WB on the on the map. And I go down there for my first day on the job, and I walk in, and these three writers look at me and you know, who are you? And say, Well, I'm I'm the new writer, I'm Paul. What do you mean, the new writer? Well, JJ just hired me and told me to come down here. Well, they were all planning on getting their friends into the staff. They didn't know that JJ was hiring this kid with no experience whatsoever. So we go and I spend like five or six hours there, and at the end of the day, the room ends, and two of the writers leave. And this one writer who was sort of the de facto writer runner of the room because she was a senior writer. She's kind of stacking papers and stuff. And I'm I'm sitting there all wide-eyed. And, you know, so I stand up and I try to be nice and say something like, Well, I'm so excited to be here, you know, can't wait for Monday or whatever. And this person looks across at me and says, Let me just tell you something. We don't want you here. JJ hired you just to get back at us. I'm sure he doesn't even like you. No one wants you here, no one's gonna like you. The best thing you can do is just stay out of our way. And she walked out of the room. And that was my first day on the job as a whatever, 26-year-old or something. Wow, like wow, it was brutal. And then that season just got worse from there.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, I wonder if that's the reason why the show kind of tanked after that. Because if you remember, the show it came out splash, she won the Golden Globe, like it was this big, and then it it just it just fell off. And they and it ended up the show ended up ending kind of rather quickly after she cut her hair, and that was. Whole kind of silliness and stuff. Do you think some of that had to do with like some of the resentment in the room?

SPEAKER_02:I think so. I mean, I was there that season, she cut her hair, and it was just kind of, you know, we would work, and and of course, I didn't know anything because I was brand new. And these three others, all due respect, they looking at them through the lens I have now, they were not very good writers. And so we didn't know what we were doing. And then JJ would come in once or twice a week and he'd look at the board and the cards we had up, and he'd go, No, no, no, no, no, that's all bad. And then he'd leave. And that's why JJ got this reputation, and and it and it was accurate of rewriting all the scripts like overnight. You know, we'd have a script that was gonna start prep the next day, and the script was horrible. And so JJ would just take it and he'd go that night and completely rewrite it. But the more that season went on, the more you know, alias started to go. They cast Jennifer Garner, you know, he had movies going then. He was already in negotiations for the Mission Impossible thing, and he just was kind of checked out. And I mean, I say this with all the love of my heart for JJ. He he taught me a lot, he's still great. I haven't talked to him in a few years, but but we have a completely fine relationship. But he just wasn't there, and the rest of us didn't know what we were doing, and there was so much animosity, you know. And and the thing that was really unhealthy is the the energy these people would expend every day on how much they hated him, and then when he would show up, it was JJ, oh my gosh, you're so amazing. We love you so much. You know, it was it was the Hollywood smile. Oh, it was the most bizarre thing to experience, and it was it was real, it was a real test for me to get through that that season. I wanted to quit many times. I I actually, this is a it's a terrible story, but it's an epiphanal moment in my career and and sort of in my maturity as a man. At one point, midway through the season, I walked into Matt Reeves' office and I started to cry. And I standing there in front of him, and he's looking at me from behind his desk, and I'm crying, going, I you know, I don't think I can take it anymore. And they're just so mean to me, and you know, and I don't know what to do. And Matt Reeves is just staring up at me, and he goes, I'm sorry, I can't help you. And I just, and it was one of those moments, Jimmy, where I was suddenly outside my body looking at myself, and I realized, oh my gosh, what am I doing? He's exactly right. Oh my gosh, I'm not an eight-year-old child. And it was a huge moment for me. And I was like, Oh, yeah, okay, I get it. And I turned around and walked out, and it was it was it was one of the most humiliating moments of my life, but also one of the greatest life lessons because it was like, nobody's coming to save you. Get off the floor and save yourself. Yes, yes.

SPEAKER_00:And he probably mustered as much empathy as he could just to say that.

SPEAKER_02:Yeah, and I'm sure he got into my office. You I mean, you know, he's the executive producer, he's the in-house director, he's editing, you know, his partners checked out on another show. And here comes this staff writer going, they're being mean to me. But it was like, if I ever see Matt Reeves again, I want I'm gonna thank him because it was he couldn't have said anything better in the moment.

SPEAKER_00:Just don't get emotional when you see him. That's awesome. Uh you know, and to JJ's defense, if you around that time, right? He was he like he said, alias was launching, and then right after that was lost, and then he went right into Mission Impossible three. So he probably would admit looking back in that early on in his career, in terms of how quickly things were moving for him, in terms of so I don't think he would have probably an issue even with that, and saying, like, it was probably difficult for him. The um, so probably like a show like judging Amy, part of what it offered you was that kind of level of cool headed, the adults are in the room, the adults are running things, and that kind of stability that that's really kind of where you started to grow and become a writer.

SPEAKER_02:Exactly. Because that's because, like I said, I you know, I had done the Snoops thing, and they actually, I didn't even tell this part of the story based on my freelance, which which was received fairly well, they offered me a staff position, and I was on Felicity, but I was hating it, so I was gonna jump ship and go to Snoops. Well, Snoop's got canceled about two days after they offered me the staff position for the back nine, it didn't even get its back nine. Um, so there was that, and then Felicity, and then I did another show that was 13 and out, and then judging Amy just again, the grace of God, a blessing from God. That, and I do believe when I interviewed for that job, uh, I interviewed with Barbara Hall and I told her that story I just told you about Felicity. And I believe that's why she hired me out of sheer sympathy, not even empathy, you know, charity work. And uh, and it was a blessing because then I was I was with adults and I was with a a show that was operating at a very high level, you know, it was a top 20 show then. And and that was before streaming and you know, all that. And um it was, it was, it was just a fantastic place to end up after you know the couple of years of experience I had.

SPEAKER_00:Did you at one point run a room? Were you a showrunner at one point?

SPEAKER_02:Yes, yeah. So on I uh I was a supervising producer on leverage, that's where I worked with John Rogers, and I I wasn't the showrunner ever on leverage, but I I handled running the writer's room whenever we shot up in Portland, and the room was in LA. So whenever John was up in Portland for his episodes or he directed occasionally, then I was running the room. And then we went from leverage to librarians, which John also created and ran, and I was his number two on that. And after season one, John got a pilot at NBC very unexpectedly. Um, we were we were actually prepping season two when John's pilot got picked up at the 11th hour. So he left. He went to NBC to do his new show. Um, or I'm sorry, not a pilot got picked up, his pilot got picked up the series. So he had a series on the air at NBC. So he left, and it was like, I remember walking in that morning and he's like, Gio, you have the con. And I was suddenly the showrunner of the librarians, and that whole season two, I was the show runner. Um, so I and that was really that was a crazy year because the librarians was at the time the only independently produced one hour on television. It it wasn't, it was electric entertainment, Dean Devlin Studios who produced it. And the studio took great offense to John leaving to go to NBC. And in this really bizarre sort of, I could only equate it with like cutting yourself. Like they took it out on their own show to punish John in some weird way, and so it was you talk about being trial by fire, throwing into the fire. That that year that I ran that show was unbelievable. But but yeah, so I ran that, and then after on NCIS New Orleans, uh I was the number two there. I didn't show run, but I but I ran the room.

SPEAKER_00:What's the what's the difference that you learned or some takeaways of um when you when you reach a kind of a leadership level in the writer's room? Um what are what are some things that were challenges, some things that were uh you really enjoyed? Um what in terms of once you get to that level, because you're you're um just just so that people understand, and maybe you can also explain a little bit of this is once you reach that level, you are producing the show. You're not just writing it, you're producing it. You're you're um if you're not on set, one of the writers is on set, and they're making sure that the director knows you can't do this, you can't do that, because that's not happening until four episodes later or something like that. There's a there's a real sense of of um level of of of um production savvy you have to have, uh, even then also being then helping with the editing of the sitting in the edit bay uh as a showrunner, uh as you're cutting the episodes. So can you just talk a little bit about that in terms of um moving from just being a staff writer to being basically in charge?

SPEAKER_02:Yeah, it's I I think something that that a lot of people don't understand about it is when you're you know, the dream is oh, I want to be the showrunner, I want to have my own show. You do probably less writing than you know the the mid-level people on your staff because you have so many other responsibilities. Yes, you're rewriting a lot of other people's scripts if if that's the case, but it's what you said, you're you have to produce the episodes, and that goes everything. You're in every meeting, you know. You you're in the meetings to like who what directors are you gonna hire in the tone meetings with the directors, in the you know, the meetings with the costume designers, in the props meetings, in the stunts meetings, in the production meetings, you know, you you're overseeing the editing of every single episode. You as a showrunner, you never stop moving. You're you're a shark, and you just go from putting one fire out to another to mix my metaphors. And it it's amazing how, like, what I learned, something that you never think of, but is critically important to getting that show in on budget and on schedule is like, where are you gonna park the trucks this week? Like, no one understands what a major part of a television production parking the trucks is when you're shooting on location. Um, and so everything like that, you know, the costume designer walks up to you and you know, do you want her in blue pants or you know, red pants? Do you want and then you have to consult with the DP on that? And and then it's like, you know, and the DP's like, Well, what do you want? You're in charge. And it's like, well, okay, I like the red. And then the DP will say, Well, the blue is actually going to look better in this set because of this. And it's like, okay, then, you know, it's you have so many balls in the air at once. You're you're just trying to stay sane and and remember that despite all these things you're dealing with um that are all practical, it's still you've got to make sure the story works. You've got to, it always has to come back to your core as the writer. And that's the most difficult thing is to be able to handle all those different things. You know, even when the caterers have a problem, they come to you, you know, the production manager generally, but then the production manager is going to go to the showrunner and say, hey, you know, the caterers need another thousand dollars or whatever. And but you have to block all that out to still remember, okay, this story still has to be first and foremost, because the audience isn't gonna care about all the location problems you had, or you know, the actor that wouldn't come out of their trailer, or the you know, the location you lost because of the rain or whatever. You know, they just sit in front of their screen and want to be entertained. And it's it's incredibly complex and difficult. And I don't, I think I would have completely failed at it had I not had you know 10, 12 years of of watching other showrunners do it well and do it poorly. You know, there's so many times now these these shows come in and they just hand a show over to some new writer, you know, because that's the thing now. That's the thing the agents go for is that big deal, it's the negotiation. And then, you know, for a while after I did that season on librarians, my agents then for the next few years started literally pitching me as oh, he's like the Michael Clayton of writers, he's the the fixer, you know. And so I was being put up for these shows with all these either crazy showrunners or inexperienced showrunners to go in and fix it, you know, to make the trains run on time. Yeah, because that's what it's all about.

SPEAKER_00:The fixer. I love it. Uh that's your next show, Paul. Right? The show oh that's already been done a few times, I guess. Paul, you've also got this really cool thing you've started recently, which is um uh you've started kind of a website uh to provide resources for screenwriters. You want to you want to tell people a little bit about that?

SPEAKER_02:Yeah, thank you. Um it's called screenwriting truth.com, screenwriting truth one word.com. And I I just, you know, uh you were somebody that inspired me. I I talked to you, I think, a year or so ago, and I'd had the idea in my head for a couple of months or even years, maybe. And and I just as a way to give back, and because there's so much misinformation out there, and the the internet and social media is so massive now, and I just want to try to give people the truth. That's why I named it that. Um, to just let them know there's a place they can go where they're gonna get the real story, where they're gonna hear the truth about this business and what it takes. And and there's a lot of free content on there. There's there's a post I put up every week and a half or so. There's stuff to read. Um, you can register and become part of the community. I do a free Zoom A every month where you get on for a couple hours and I can you can just ask me anything on a Zoom and we talk about whatever. There's also some stuff if people want to hire me for services, um, you know, as far as like note services or whatever, in a way to give back. And so far it's going, it's going all right. It's going pretty well. Thank you.

SPEAKER_00:Uh okay. So you one of the things that I wanted to spend some time talking about is you um there's this, there's there's this thing we call guilty pleasures, and I um I have a guilty pleasure, and that is I love disaster films. You're shaking your head because you know you know what I want to talk about. I love disaster films. Yeah, I love disaster films. I'll watch any disaster film, I love them. Um, I it's a guilty pleasure of mine. So I don't and I've got my even got my kids into them. So now my kids are always like, Daddy, is there another end of the world movie coming out? I'm like, Yes, let's go see the end of the world movie. Um, so you, my friend, wrote um one of my guilty pleasures, which is a film called Geostorm, which was a big um uh disaster movie studio film with uh with uh Gerard um uh butler. Sorry, Gerard Butler. And um and you you sometimes say to people that you'll happily refund their money, and I always give you a hard time about that because so obviously you somewhere along the way, you sat down to write a film that eventually came out on screen. I don't know if it's the film you originally intended to write. I'm curious. Tell us the story or the journey behind uh writing Geostorm. Okay, how much time do we have? Give us the abridged version, all right.

SPEAKER_02:Which I I refer to it these days now as Geostorm. Um, it was so I co-wrote it. I my the the writing credit is a co-cred co-writing credit with Dean Devlin, who is also the credited director and the producer of the film. So my last day, I'll tell this as quick as I can. My last day on leverage, John Rogers and I were sitting in the office, you know, having a drink or something, talking about the season. And somebody said, Hey, Dean wants to see you up in his office. And I had said, you remember, he was like the head of the studio that produced the shows. So I was like, Oh, so I go up there and he says, Hey, buddy, uh, I want to pitch you an idea I have for a movie. And I said, Oh, great. And he pitches me satellites can control the weather, and someone weaponizes them. He had that's all he had, and he had the opening scene. And because he was my boss, I said, That's a great idea for a movie, Dean. Um, and he's like, Good, because I want you to write it with me. And I said, Okay. And I go back downstairs, and John Rogers goes, What's that about? And I go, he wants me to write a movie with him. And John Rogers goes, Is it the satellite movie? And I said, Yes. And John's like, Yeah, he pitched that to me about three weeks ago. So I wasn't even his first choice. Um, but so, anyways, that led to me writing 14 outlines on my own. Like, literally, I came up with everything, and he would say yes, yes, no, no, and I'd do another outline. Finally, got an outline that Dean liked. So he flew, I was living in St. Louis at the time. He flew me out to LA, and so crazy the story. And he put us up in this two-bedroom suite at this bizarre little boutique hotel in West Hollywood, and we proceeded to write the movie together, which what it looked like was I was in one room, he was at the other in the other room 40 feet away. I would write a scene from the outline and email it to him in the other room, and then he would rewrite it to suit him. And look, Dean's a great producer, Dean's an okay TV director. Dean Devlin's not a writer, but he thinks he is, and he was still basically like I had that weird thing that he was my boss, even though we were co-writing this. Um, so, anyways, we finally got the thing written. And long story short, Skydance, um, David Ellison's company made a preemptive bid on it because Dean had done something very smart and teased it to Skydance and Amy Pascal at Sony that it was going to hit the town and have this huge bidding war. So, Skydance made a preemptive bid and paid a fortune for it. Like it was at the time, it was the biggest specs sale in several years. And so I thought, great, my ship has come in. You know, this is fantastic. And and also part of the deal he got with Skydance is he was locked in as director, he was locked in as a producer and the co-writer with me. Well, Skydance's deal was at Paramount. So Paramount reads the script, you know, and it's not that great. Um, because like I said, everything I wrote, Dean would take and rewrite in the other room. Um, so Paramount had a bunch of notes. We sat down with Brad Gray at the time, head of the studio. I'm in there with like All the big players in Hollywood, and they're going through saying everything that's wrong with the script, and I'm sitting there silently agreeing. And so Dean refuses to do any of the notes. Nope, my script's the way it is. I'm gonna direct that. Wow. Well, Paramount says, No, you're not. We we're not gonna spend a hundred million dollars on that screenplay. And Dean says, Well, that's the only one I'm directing. And so they fired us as the writers, which happens all the time in features, right? So my my dream job was suddenly, I was suddenly fired, and they brought in the Mulronis, who are a fantastic husband and wife writing team. They wrote all the Robert Downey Sherlock Holmes movies, really great writers. They do a pass on the script that's fantastic. And to toot my own horn, probably 60% or more of what they wrote was kind of my original vision that I wrote before Dean rewrote me. And it's a great script, and everybody at Paramount's excited. And Dean says, No, I'm not going to shoot it. I'm shooting my script. So Paramount put the movie in turnaround. So we were dead. So nine weeks after they had paid$1.2 something million dollars for the script, the movie is in turnaround and dead. One week later, Jimmy, and this right here is how movies get made in Hollywood. One week later, Dean is at a school function for his daughter at whatever middle school is, you know, that she goes to in Santa Monica or wherever. And he's standing next to another dad. The other dad, and his name escapes me right now, but at the time he was the head of production at Warner Brothers. And they're just talking shop. You know, what do you got going? What do you got going? And Dean says, Oh, I've got this big giant disaster epic, you know, that uh that I that I just got back from Paramount. You know, they wanted to ruin it, and I just got it back. And the guy goes, Is there a part for Gerard Butler? And Dean goes, Why, yes, there is. He could be the lead. And the head of production says, Well, and this is like, I don't know, it's first of the school year. It's probably like early September, right? At this time. And he goes, Well, if we don't put Butler in a movie by the end of the calendar year, we owe him$30 million.

unknown:Wow.

SPEAKER_02:One week later, that movie had a green light. Long story short, Warner Brothers spent about$160 million in order to not pay Gerard Butler 30 million on his deal. That's how movies get made. That's how Wonder. No wonder it didn't show up at the Oscars. And then the writing part of it is cut to I ended up going through arbitration, WJ arbitration with that, and actually had to arbitrate against Dean just to end up sharing credit with him because he was arbitrating for sole writing credit of the movie. It is just craziness. It was absolute insanity.

SPEAKER_00:Are you? I don't know if you're allowed to say, but did you what would have been his logic behind that?

SPEAKER_02:Of well, I will say this publicly because it's the truth. So, you know, there's no slander or anything because it's the truth. What the first two, three weeks of the movie, I was on set and I was doing rewrites every day. You know, how you rewrite on set for Andy Garcia and these other writers or actors, excuse me. And what I did not know was happening is every day I was turning in pages, he was having the script coordinator generate a new cover page, title page, that said, you know, Geostorm written by Dean Devlin and Paul Gio, revisions by the Mulronies, current revisions by Dean Devlin. So when I saw the arbitration, you know, he had all this evidence in quotes that he had done all this rewriting and it had and it was all me. And I don't know why. I'm sure he had his reasons for wanting to do that. But like to this day, I say the greatest thing I've written in my career is my letter of arbitration because I'm one. It's really pathetic and sad that that's how it works in Hollywood. But yeah, I had to arbitrate against him just to share credit with him.

SPEAKER_00:This is the this is not uncommon. A lot of people don't realize this is not uncommon. How many writers have to fight for credit? Um do you uh so okay, but I know you're personally disappointed also with the script and or what with excuse me, how the film turned out. Why? What what is it? What is it that what I mean? I know you said the rewrites and everything, but um uh just help people understand because you know, kind of like what we were talking a little bit before we started recording is this idea that the reason why I wanted you to, and you you're you're so transparent, and and that's what I love about you. You're you're very open and honest. I guess you won't be working with Dean Devil anymore, but uh you won't be working on the next Stargate. I didn't get called for the leverage reboot, by the way. Yeah, but um the uh I think this is such a good valuable, by the way. This is a classic Hollywood story, like you said. Um there's so many lessons to be learned here for young emerging uh writers, because in a sense, right, this is what people see almost as the as the ideal success story, right? I'm gonna write a big budget studio film. I'm gonna write a big budget studio film with a big time producer, and um, and that's my ticket to to to you know to to glory, right? Like I this is gonna be my big and it didn't work out for you in the way that you had thought. And um lessons learned. What what what do you looking back on it now? What's your best advice? Um, pro and con, what's your best advice to emerging filmmakers having gone through this experience?

SPEAKER_02:Yeah, it's a great question. And and there's there's kind of two parts to my answer that I want to really make sure people hear. And the the first thing is the I'll I'll sort of answer the second part first and then go back. Is so when that movie was about to premiere, you know, it was there was a lot of hype. You know, Warner Brothers was swinging for the fences, they had had so much money in it, you know, there were ads everywhere. It was a giant movie coming out in October of that year, 2017, or whatever it was. And the week, two weeks before that movie came out, my agents at the time had set up multiple meetings for me in the feature world. Like, because I had really no experience at all writing studio features before that. And I was I had meetings. People wanted to meet with me as a writer to either hear about the property they had to pitch me or for me to pitch, you know, movie ideas to write. The movie came out on a Friday, on a Thursday, I think actually. And by that Monday, my agents called and every one of the meetings had been canceled. And I was officially in movie jail, which is a real thing. And and to this day, haven't been released. I I've had a couple of work furloughs, but I'm I'm still in movie jail trying to to get paroled. Um, so that's that's the reality of things like that. What happened with the movie for me is I was pretty proud of the outlines I wrote and the the the that sort of non-existent first draft that I did write because mine was all coming from character. I felt like mine was a story about two brothers that were both trying to earn their father, their dead father's respect and going about it in opposite ways, and only eventually could come together through this disaster to realize that they're better when they're brothers, when they're when there is that family love and that respect and everything. And I was really kind of proud of the work I had done that I had managed to create a what I thought was a real character piece amidst all this stuff. And and that's what Dean loved too when we set out to write it. But what where I think the movie started to go off the rails and then just continued over the cliff is you know, Dean has his own visual effects company at Electric Entertainment and everything. Before we had even finished writing the screenplay, his company was creating the visual effects. They were Dean's idea of how to make the movie was it's not a story about people, it's you have these six or seven or five or six massive sequences, and you just fill in the other stuff with talk. Hey, some movies have been that way and been successful and stuff. That to me, that's my own personal opinion of why the movie failed. And because there's just no authenticity to the film. There's there's no, I mean, if you check out, it can be like a fun popcorn thing, and and it's kind of you can look at it as kind of campy and and it works on that level. But the reason it pained me so much is because when I sat there that night in that theater at the Sherman Oaks Galleria watching it was because I knew that we were trying to make a really serious like motion picture. Like I was, I wanted desperately to be known as like, oh, this is a guy that brought character to a giant disaster film. And it was the other way around. And that's what broke my heart so much. I remember that night I walked on Ventura Boulevard for probably two hours. Um, but that's that's where I think went wrong. And then the whole movie jail thing, you know, that's the lesson learned. But if I would never tell uh an up-and-coming writer if they're in that situation, to say no. Like if you get that opportunity, take it and do the best you can. You know, there you're obviously I wasn't in a position to die on any hills because I would have just been let go. I fought my little battles, but in the end, I wasn't in charge. And yes, it's cost me in the feature world since then, and that's been very hard to take, but I I made incredible life life lessons from it. I got paid, you know, and even though the movie bombed everywhere, God bless the wonderful people of Indonesia who have terrible taste in movies because they've they've allowed residuals to still pour in.

SPEAKER_00:Um me too. I bought I bought a ticket. You got some of my money.

SPEAKER_02:Thank you. And so, and that's really the lesson is you know what? Sometimes you just gotta take your lumps. You know, you you you don't ever want to have that reputation early on as somebody who's difficult to work with, or somebody that you know is precious about their words, you know, that can come later if once you achieve success, you can be whatever kind of person you want. Hopefully, you won't be like that. But early on, you got to, I think, go for every opportunity you can get, and you just do the best you can and have an understanding that it's Hollywood, it's not writing novels for random house. So a lot of your stuff isn't gonna turn out the way you want it. But if you're okay with that, the checks cash. That's right.

SPEAKER_00:Well, that's that's exactly right. I think this is a great kind of place to wrap up our conversation because it really brings home, I think, a lot of what we've talked about. And that is um oftentimes, and it's not just those of us in the entertainment industry. Uh you you can see this happen in all different um um uh work environments all over, is is the it's cliche, but it's true. And the the the it's about the journey, it's not about the destination. As a writer, 100% you can't put the the the the kind of the the thing that's going to make you or break you is going to be um that one script or that one project. It really is about doing the best you can when given the opportunity over and over again. It's uh you have to find joy in the writing, you have to find joy in the process because, like you said, part of the nature of this business is it's gonna rob you of that joy at the end because at some point you don't get a say, you just you just don't. That's just the way it works. There, there are unless you're Clint Eastwood or Steven Spielberg, there like I I I've said this a million times. Uh there's a reason why you can only count on one hand the people who have that kind of power, because they're the only ones that have it, they're the only ones. The rest of us have to kind of play by these um weird arbitrary rules that sometimes means that uh what you set out to do doesn't always show up on screen. And you if if that is where you're trying to seek satisfaction in your career, it's going to be a very, very frustrating career. You have to love the process, you have to love being a writer in order to um make it in this business. Am I am I overstating this too much?

SPEAKER_02:I don't think it can be overstated. No, I you know, I I I tell people I've had times in my career, you know, where I was eating at Nobu, and I've had times where I was eating top ramen, and I wouldn't trade either one of them. Like it's I I we're all horrendously overpaid for what we do, and that's just a blessing from the Lord. But I would do this job for whatever they paid me, if it was strictly top ramen all the time, because I'm a writer, you know, and we live by our wits, you know, we take the hits and we walk them off, and then we use that scar for another story. And I'm just I I couldn't love this job more. And I my success, my reward is in the journey, is in the work, is in challenging myself every day. It's not looking for the validation of other people, looking for box office numbers, looking for Nielsen ratings or Emmys or Oscars. That's that's chasing something that's just gonna leave you disappointed. Even if you win the Oscar, then suddenly it's like, well, what are you gonna do next? You know, and you have to love what you do, and then you will truly be successful no matter where you're at financially.

SPEAKER_00:I don't know this for sure. I can't I can't tell you without any uncertainty that this is true, but I think it's about 99.9%. I'm pretty 99% certain this is true. The least fulfilling moment in an artist's or filmmaker's career is when they win the Academy Award. It's the least fulfilling, it's the least fulfilling moment because of what you just said right there. Because this business moves immediately to what's next. We're trained what's next. And it is the least fulfilling thing when you reach that point, if that is where you have put your emphasis. And that is something that for those of us who are followers of Jesus, that is something that should be different about us, right? It should we should have a different measure for success. We should, I don't know if we always do, but we should have a different measure for success. We should have a different measure for what where we draw our contentment from. And uh, and I think you're just hitting the nail on the head right here, is that if you make that thing the thing that's going to satisfy you and and and kind of the purpose of why you're doing it, then then you will never truly be satisfied. You'll never truly feel fully understand your purpose and be able to live in that purpose that God designed and created you. Uh, if you're gonna be a writer, you've got to experience that pleasure in that moment that God has given you that ability, and you are actually operating in the talents and abilities that He's given you.

SPEAKER_02:Yeah. Well, I I I'm so glad you you're ending with this because it's, you know, I I often and what I do every day is think about Colossians, I think it's 323, about you know, whatever you do, work at it as though you're working for the Lord and not for human masters. And I my I'm at a point right now, career-wise, where I'm probably earning less than I've earned in a really long time, but I've never been more satisfied or or more content in my career and with myself than I am right now. And it's all because of my faith. When I I'll tell you, people around me, my girlfriend will tell you for sure, when I was making the most money I earned in my career, I was the unhappiest. And that was because I was in a place during those years where Christ was second or third or fourth on my list of priorities. And you know, it's like you you that that old saying, you know, you hit rock bottom, Jesus is the rock at the bottom. And uh it's I couldn't be, I mean, you you know what I've been going through lately, career-wise, and stuff, and I could not be more at peace right now and and happier. And I also feel like genuinely feel like I'm I'm writing the best stuff of my career, and because it's that journey, man, it's the journey, you know, the destination that's gonna come later for all of us.

SPEAKER_00:I love it, I love it, Paul. Thank you so much. This has been such a joy to talk with you, my friend, and I just love your honesty, your transparency. You know, one of the things I think about you, Paul, is you're almost you one of the things I love about you is you love writers. I do. You love right, and it's almost you're almost pastoral towards them. I don't know if anyone's ever told you that, but it's almost like you have a pastor's heart towards writers. You love writers, and I love that about you. And thank you for that. Thank you for the way you care for other writers and and um care about the craft. And um, thank you for your friendship. Thank you for just um all that you've done. And um always love to kind of close our podcast by praying for our guests. Would you would you allow me to pray for you to close our conversation?

SPEAKER_02:I I would if you let me say one thing before you do, and that's part of where I'm at right now in my faith and in my life. I I don't want to under, you know, sell this because is finding you and and God leading me to you and to act one and everything. That was really one of the the just jump starts to where I'm at right now. So I I really owe you a tremendous amount of gratitude.

SPEAKER_00:Oh, you're very kind. I'll c I'll edit that part out. Heavenly Father, just um thank you for Paul. Thank you for this opportunity to be able to just stop and pray for him. And uh what a great conversation. What a um just I know God, you're doing so much in his life right now. You're you're working on his heart in so many different ways. And God, I'm just so grateful to you for uh just who he is as a friend and as a writer, the way he cares for other writers, how passionate he is about other writers. Uh, just thank you for um just all of that. And and uh just pray, God, that you would um bless Paul, um bless his career, bless his work, um, bless his process, bless his creative process. God, I pray that that um that he would be filled with uh your creativity and your ingenuity and be inspired by uh just um uh being uh uh living a life that's pleasing and honoring to you, God, would inspire him um in his craft. And um even as he gives back to other writers, just pray a blessing upon that and uh his uh his writing website and just everything he's got going on and bless his family, bless his relationships. And God, we just um thank you for this opportunity. Pray this in Jesus' name in your promise as we stand. Amen. Thank you for listening to the Act One podcast, celebrating over 20 years as the premier training program for Christians in Hollywood. Act One is a Christian community of entertainment industry professionals who train and equip storytellers to create works of truth, goodness, and beauty. The Act One program is a division of Master Media International. To financially support the mission of Act One or to learn more about our programs, visit us online at Act OneProgram.com. And to learn more about the work of Master Media, go to MasterMedia.com.