Act One Podcast

Act One Podcast

Screenwriter Buzz Dixon

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

Act One Podcast - Episode 35 - Interview with Screenwriter, Buzz Dixon.

Buzz Dixon writes oddball TV / movies / games / comics / novels, putting words in the mouths of Superman, Batman, Conan, The Terminator, Optimus Prime, The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Mork & Mindy, Scrooge McDuck, Bugs Bunny, Yosemite Sam, plus more G.I. Joes and My Little Ponies than you can shake a stick at. His short fiction appears in Mike Shayne’s Mystery Magazine, the Pan Book Of Horror stories, National Lampoon, Analog, and numerous original and “best of” anthologies. If you were a kid in the 70’s or 80’s, there is a good chance, Buzz wrote for one of your favorite cartoons.

The Act One Podcast provides insight and inspiration on the business and craft of Hollywood from a Christian perspective.

Lou Scheimer was on vacation in Hawaii because it was hiatus season. And Arthur read my short stories and sent them to Lou via FedEx. And then in the interim, I come in with the premises, and Arthur looks the premises over and he goes, Well, you know, they're close enough. I mean, he's he's clearly got the ability to tell a story. And he leaves the premises on Lou's desk. So when Lou comes back from Hawaii, he's got my premises sitting on his desk. And Lou called up Arthur and said, Um, you know, I really don't know who we should hire. If we should hire the guy who wrote the short stories or the guy who wrote the premises. And Arthur said, They're the same guy. And Lou said, get it.

James Duke:You are listening to the Act One Podcast. I'm your host, James Duke. Thank you for listening to our little podcast at the end. If you like what you hear, be sure to subscribe to our podcast. Leave us a good review. My guest today is screenwriter and author Buzz Dixon. Buzz Dixon writes oddball TV, movies, games, comics, novels, putting words in the mouths of Superman, Batman, Conan, The Terminator, Optimus Prime, The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Mork and Mindy, Scrooge McDuck, Bugs Bunny, Yosemite Sam, plus more G.I. Joes and My Little Ponies that you can shake a stick at. His short fiction appears in Mike Shane's Mystery Magazine, The Pan Book of Horror Stories, National Lampoon, Analog, and numerous original and best-of anthologies. If you were a kid in the 1970s or 80s, there is a good chance Buzz wrote for one of your favorite cartoons. He is a wealth of knowledge, and we had a great conversation. I hope you enjoy. Buzz Dixon, welcome to the Act One Podcast. It's great to have you on. Thank you very much. I enjoy being here. I uh we were just chatting and I was just saying how much I've been looking forward to this. And you you've heard this probably often, but I was uh looking at everything you'd you've worked on in the past, and I thought, man, this guy wrote half my childhood.

SPEAKER_00:Well, I hope it was, I hope it was the better half.

James Duke:Yeah, it was. I mean, I, you know, you uh you worked on so many shows in the 70s and 80s at a time when animation was dominant in the um uh Saturday mornings and what I call coming home, the the the afternoon block, coming home from school. And we would rush home. And so for me, I'll just give you a quick. So for me, uh afternoons after school were Transformers, G.I. Joe, Key Man, and and then like a collection of either Thundercats or um you know, whatever else. Um, but but the mainstays for me were uh G.I. Joe and Transformers. And then of course Saturday morning was full of you know whatever the networks you know put out back then. Um so uh so yeah, so I just look back at that and I think, man, this guy. So you have you obviously have had uh a pretty varied career with all the different things you worked on. I'd like to start, if we could, um, just kind of back at when you first got started. So I'd love to know, did you always want to be a writer? Was that something that you uh grew up passionate about? And like what was that encouraged uh early on in your life?

SPEAKER_00:Well, um I wanted to be creative in some form. And uh as a little kid, I was always drawing pictures. Um as early as the third grade, I was trying to write stories. Um believe it or not, I tried writing a science fiction uh stage play when I was in the third grade, you know. And I I I quickly realized about like two pages in, I have no idea what I'm doing. So I stopped at that point. But um I was always a creative kid. Um my family moved a lot when I was growing up. We we lived in 20 different houses before I graduated high school. That'll give you an idea of how much we moved. And so almost every year I was in a brand new class with brand new uh classmates, and I gravitated towards science fiction fandom because the nice thing about science fiction fandom was you were never further away from your friends than the mailbox. You know, every time, every time we moved, a change of address, and my friends were waiting for me when you know we got to the new house. So getting involved in science fiction fandom, I became interested in writing science fiction stories. About age 13, I began seriously writing stories with the intent that I wanted to submit them. Uh, and I actually did start submitting when I was uh somewhere between 13 and 16.

James Duke:And when you say and when you say submit, so back then, and what time period are we talking about?

SPEAKER_00:So you like wow, this would have been uh 66 to 70.

James Duke:So at that time there were uh like fan magazines and things like that that you would you can submit to. Yeah, yeah.

SPEAKER_00:In fact, the the very first published byline I ever got was in a magazine that's now the magazine is now called Midnight Marquee, but back then was called Gore Creatures. Um Gary Svela was was and still is the editor of it. And uh Gary published the first thing I ever wrote that I got a byline on. And it was it was a critique on uh um how how fake uh rocket ship sets looked in most science fiction movies because they were they were crappy. I mean, let's be honest. 1950s uh I think Cat Women of the Moon, it has like a film reel hanging up in the wall. It's like that's supposed to be science fiction. I mean, come on, but anyway.

James Duke:Um although, although, although I just watched Forbidden Planet again the other day, and that movie holds up. That is that is a spectacular, and that set was unbelievable.

SPEAKER_00:They spent a ton of money on that movie. Oh, they must have that set. I was so impressed with that set. Oh, and and well, do you know the origin of Forbidden Planet? No, no, what's the origin? There, there was a special effects company. Um Jack Rabin and uh oh gosh, what was the other guy's name? Oh, I I'm blanking right now. The the third silent part partner was named DeWolf. I can't remember the name of the second guy in it. But anyway, it was a small special effects company. They mostly did titles and stuff like that for industrial films, but they had a clever way of drumming up business. They would figure out a really cheap, inexpensive special effect. They would write a story around the special effect, and they would pitch it to low-budget movie companies. And when the company would buy it, they would uh they would get to do the special effects. So they did um War of the Satellites for Roger Corman. They did uh Unknown World, which is about this tank-like thing crawling into the center of the earth, um Monster from Green Hell, which had stop motion, um, giant wasps in it. Wow. Um, let's see what else. Oh, Kronos, you know, Kronos. And they had they came up with this great idea for a movie set on a planet that was populated by invisible monsters because and their logic was impeccable. You can have as many invisible monsters as you want, and so they they came up with this thing and they pitched it to several low-budget studios, but somehow um a copy of the pitch wound up at MGM, and MGM was seeing how successful uh the thing and uh the day the earth stood still had been for other companies, and they said, Well, we ought to jump on this sci-fi bandwagon. And so they bought it and they said, We're gonna buy you out completely, we're not gonna let you anywhere near the project, but um so they bought them out, and that became the genesis of Forbidden Planet, the the idea of a planet full of invisible monsters.

James Duke:It it went from being a pitch to try to find the lowest, the cheapest, the most affordable way to do effects to being the really expensive effects.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, I mean it's it's a tremendous, and it does yet, you know. You look at it today and you just say to yourself, this is an artifact of the 1950s, so it reflects that design sensibility, that level of of knowledge about science and psychology that they had then. But once you once you do that, it's like, well, this movie is it hangs together. It it really works.

James Duke:It does. It it it really it really does. And I think that that, and I sorry, I didn't mean to cut you off as you were we'll we'll get back to you. But isn't that what great science fiction does? Is that like watching Forbidden Planet, it's dealing with these basic human themes that are universal in terms of our human condition. And science fiction does a great what what's great about good science fiction is that it's deeply human, and that it's it's it's actually which makes which makes a movie from the 50s still feel somewhat prescient today because it's it's dealing with issues of fear, fear of the other, fear of the unknown, um, the idea of control and power and manipulation. These are all things that we deal with, you know, every generation and every every time, right?

SPEAKER_00:Yeah. This is this is one of the reasons why a lot of 80s uh sci fi films, uh lower budget sci-fi films, don't hold together because they they they had no consideration of this. It was just how how fast can we knock out an imitation of something somebody else did?

James Duke:So let's get back. I we can we can I I I expect we're gonna we're gonna enjoy uh talking about all these wonderful things. Uh but but back to so you submitted um to um started submitting to these fan fiction magazines and uh fanzines and also um professional science fiction magazines.

SPEAKER_00:I mean, I submitted to uh uh Galaxy if uh fantasy and science fiction, fantastic, amazing. These were all digests at that time. Um fantasy and science fiction and analog are both still being published. I I it took me 50 years, by the way, but I finally cracked Analog. Um but I've been yeah, I was writing stories for them, submitting them, and uh you know spending a small fortune in in uh mailing fees because back then you back then you had to put it in a self-addressed stamped envelope so they could send it back to you when they would reject it. And you know, I I I I went through a lot of mailings, let's just put it that way. Wow. That's that's what you need to do as a starting writer. You need to write, you need to submit it and get feedback and get feedback. And a lot of times uh today uh they have um fan fiction sites where people can literally post anything, and you get the feedback directly from readers, which uh, you know, is better than nothing. But it really helps when you have uh editors who will write back to you and say, you know, we I'm rejecting this, but here's why. And and they would give you an insight. I mean, I I I don't have the letter anymore, but John W. Campbell of um Analog, um, and he was like he was like one of the the greats of science fiction. He he goes all the way back to the 40s. He wrote Who Goes There, which is the basis of the the thing movies. Um Campbell goes from like the 40s up through the 70s, and when I was in the army, I submitted a story to him, and he actually wrote back like a two-page letter, one or two page letter, where he said, I'm rejecting this, but I like the thinking on it, and here's why I'm rejecting it. And it was it was a very good insight because it gave me uh said, Okay, here's here is where I'm deficient, here's where I need to apply myself. Um I had I had been, I'll I'll I'll give you a really brief recap to get me into animation so we can move along. Uh I wanted to be a movie director when I was in high school, and I was I was writing scripts and short stories, but the ultimate goal was to be a director. And in 1972, I was uh drafted. I I I tell people I won I won a lottery that gave me a free all-expense paid trip to Korea, uh, which was lucky because I met my wife there. So I'm not knocking that. But in any case, I was drafted in 1972. The army figured, well, he can he can string three words together, so let's make him a newspaper editor. And I post newspaper for uh a year, and then I was um I was on the um um, I was the what would you call it, the um NCOIC, non-commissioned officer in charge of public affairs for the fourth U.S. Army Missile Command, uh, which um no, excuse me, not for U.S. Army Communications Command. Uh the Missile Command was the post newspaper. Uh it was with the fourth with the U.S. Army Communications Command, which uh I was at I was writing press releases and stuff that got uh you know anonymously, but it would end up in like Time Magazine, Newsweek, things like this. So I I had a chance every day to to hone writing skills. Yes. You know, 99% of the time it was what we called grip and grins, where you know somebody's getting an award, and you just write the caption of these two guys shaking hands. But it it gave me a chance to work at writing.

James Duke:And and and especially even something even that specific where it's everything's similar, you have to figure out how how do I say the same thing differently.

SPEAKER_00:Oh, yeah, yeah. It uh it is a challenge. In any case, when I got out of the army uh in 78, um uh I was married, uh, we had a child. Uh I had been accepted by uh the University of Southern California to their film school, but the film school wouldn't start until fall. And I was discharged in February. So my wife and I decided we'll come out to California. Uh, I would try to find a job in the movie industry as a driver or in the mailroom, gopher, something like that, just to get my feet wet until school started. And I literally started at Universal Studios just handing my resume out. I started there and I worked my way all the way down to Filmation Studios. Filmation wasn't 100 on the list, it was literally 98. I'm not kidding. And so I go into Filmation Studios and I've got my resume and go up to the receptionist. This is probably March, uh, March, early April 78. And I go in and I say, uh, I I'm I'm looking for a job and I'd I'd like who do I who can I give my resume to? And the receptionist said, Well, are you looking for a job in animation or live action? Well, I don't know anything about animation, so I said, Well, live action. And she says, Wait a minute. And she takes my resume and she goes in the back, and then she comes out and she says, Arthur, we'll see you. And this is Arthur Nadell, who was the producer of the live action shows at Filmation Studios, because Filmation primarily did animation, but they also did a number of live action shows. And it turns out it was hiatus season. And in animation, hiatus season was that period between the time you finished the last show that had been bought for the previous season, but the networks had not yet started buying shows for the next season. So there was like a three-month period where nothing's happening. And um, if the studio was big enough, they would keep you on and you would be developing ideas for them. Uh, if they weren't big enough, they would cut you loose. And at Filmation, it was virtually a ghost town at that point. And Arthur was sitting in the back with nothing to do, and he goes, Yeah, send this guy back, give me some anything to kill an afternoon. So I go back and I met Arthur. And Arthur, I gotta say, one of the sweetest gentlemen I've ever met in the business. Arthur is is just a was just a wonderful, nice person. And we struck up um, you know, a good rapport with one another. Um, he was asking me about what I had done in the army and my plans and this and that. And I mentioned I had written a number of short stories. I hadn't sold any, but I had written them. And he said, Well, if you're ever around here again, uh drop off you know your short stories. I'd be happy to take a look at them. Well, you know, you don't have to hit me over the head with a shovel. I go back to the apartment where we're staying. I dig out my short stories from uh the suitcase they're buried in. And about a week later, I go back and I say, Well, Arthur asks to see these, and say, okay, go on back. I go back to see Arthur. He thanks me. And then he says, You know, we've got um a show we're developing and we're having a difficult time coming up with premises for it. So now I can't ask you to do any work because if I do, I have to pay you. But if you on your own were to come up with some ideas and wanted to show them to me, I'd be happy to take a look. Wink, wink, nudge, nudge. So, you know, again, you don't have to hit me with a shovel. I go back, I pull out my typewriter, I I spend about a week coming up with six or eight ideas. And a week later, I go back and I drop the ideas off with Arthur. What I didn't know was this. Lou Shimer, who was uh with Norm Prescott, was one of the two principals at um Filmation. Lou Shimer was on vacation in Hawaii because it was hiatus season. And Arthur read my short stories and sent them to Lou via FedEx. Now, this is 1978. Sending something FedEx to Hawaii is a big deal in 1978. Yes. Sends my short stories to Lou in Hawaii. And then in the interim, I come in with the premises. And Arthur looks the premises over and he goes, Well, you know, they're close enough. I mean, he's he's clearly got the ability to tell a story. And he leaves the premises on Lou's desk. So when Lou comes back from Hawaii, he's got my premises sitting on his desk. And Lou called up Arthur and said, Um, you know, I really don't know who we should hire, if we should hire the guy who wrote the short stories or the guy who wrote the premises. And Arthur said, They're the same guy. And Lou said, get him. And so Arthur said, Would you like to write, you know, uh a script for us? And well, sure, absolutely. So this is maybe April, early May of uh 78. I wrote a script for a show called, no, geez, Starlight and Moonlight, Starlight and Sunlight, Bright, something like that. Um, Jebuzite and Amalachite, I can't remember, but the the premise was there were two twin sisters, one of whom got her powers from uh her superpowers from the night, the other one who got her superpowers from the daytime. And uh, so of course, obviously you've got to do stories where the the switchover is crucial to what's happening, and that proved a very difficult show for people to come up with ideas for. And even though I wrote a script for them that they bought, they ended up canceling the show before it even went into production. So um it never it never went anywhere. But I at least got my foot in the door. And after I wrote the first script and they saw that I could write uh fast and well enough to be edited, because I was terrible in those days, I'm gonna be honest. Um, I had I had a story editor, um, Len Jansen, um, who worked at Filmation get so ticked off at me one time he tried to smash my head against the wall with a coat rack. And I have to say he was justified, okay? He was not being unreasonable at that point. But um, yeah, we we we had we had stuff going on. Filmation. Uh anyway, um I got I got the gig writing for filmation. And when fall came around, uh, and most of the other people were put on hiatus, uh, they said to me, you know, we'd like you to stay and develop story ideas for us. So I'm thinking, you know, I'm making a living, I'm paying my rent, um, I'm I'm taking care of my family. I'll I'll put off um college until next year. Next year never came. Wow.

James Duke:Wow. So you and never ended up, you were accepted in the USC and never ended up going.

SPEAKER_00:Never ended up going there. No.

James Duke:Wow. That is that is so back then filmation had um a with they were a production company that would sell shows to, I guess back then it was just the networks. What is was it just CBS, NBC, ABC back then? Yeah, and and so they would sell shows. So they were selling live action and animated. Right. And um, and so when you uh started developing stuff with them, what was the transition from live action to animation for you?

SPEAKER_00:Well, the the transition occurred uh before I got there, and I never got a chance to write live action for them. I I was at one time in the live action studio because they needed space for animators in the uh um the regular studio, but uh I never got a chance to write live action for them. Um but I I I hung around with Arthur and uh all of the people working there. They had figured out a way of doing inexpensive um action adventure shows on Saturday morning. They did ISIS, they did Shazam. A friend of mine, Michael Reeves, um came up with the brilliant idea that ISIS could make things not happen. So, you know, she would show up, the damn's going to burst, and she would go, Damn, don't burst. And you know, it's like there's any number of things you can stop from happening, you know. It's like the it's the like the invincible, invisible monsters from forbidden. Exactly, exactly. They they loved Michael. I mean, they they'd hire Michael, come in and and have as many things not happen as you can think of. Uh that's awesome. They they did these shows on a low budget, but they did them with a sense of uh a sense of style, and they did them with a sense of um there was depth to them. It wasn't just knocking out uh pointless action adventure. The the one thing that filmation had going for it in those days, um they got their start when CBS wanted to do, uh I think it was CBS, wanted to do a Superman animated show. And they approached Hanna Barbera, and Hanna Barbera said, you know, our plate is full. We can't, we can't put another show in production. And Lou Scheimer was working as a background artist for um Hanna Barbera at that time. And Lou heard about this and he approached CBS and said, I can put a studio together and we can do um, you know, the Superman show for you. And he partnered up with Norm Prescott and I want to say Dan Christensen. I may be wrong here, so don't hold that, you know, don't hold that as as uh uh authoritative information. But anyway, they put together Filmation Studios. Norm Norm was an old radio guy who uh when I say radio, I mean DJ guy, who um uh got into voiceovers and uh had actually produced an animated film separate from Norm. He did uh Pinocchio in Space. Um and so they got together. It's not a bad movie, actually. I mean, when you when you look at it as a cheap 1960s animated feature, right? You go, okay, you know, for what it is, it's not bad. Um anyway, they they put together the um uh Superman show, and they were notorious for uh they were deter, they were determined to make money at every stage of production. Anna Barbera did what was called deficit financing. The studio would give them, I mean, the the network would give them a quarter million dollars to do an episode that would really cost a half million. So they would go out and find a bank and they would borrow a half million to do that episode. Then the hope was at some point in the future you sell it as a syndication package and you make your money back that way. Got it. Normally will work, but sometimes you get a really terrible show and and it doesn't, and you end up losing money. Lou and and God bless him, Lou was a union guy, even though he ran the studio, he was a union guy. He insisted on you using union talent, but on keeping the budget so low they would make a profit even off uh you know quarter million dollar budget, and so they used every trick in the book to keep the the cost down. I mean, just ridiculous stuff. You look at it now, and it's it's funny to see just what the cost-saving things they were doing. Um, when they did the Archie show, almost all the dialogue was shot over the the back shoulder of whoever was talking. So here's Archie talking to Mr. Weatherby, and then you cut like this, and here's Mr. Weatherby answering Archie. You never see their lips moving, you only see the person they're talking to. He didn't have to animate the lips moving. That's cool. And uh, when they did the Star Trek animated show, they would get these tight close-ups of eyes so they don't have to show mouths moving.

SPEAKER_01:That's the reason why I I remember those tight shots.

SPEAKER_00:And um uh they they loved characters with masks because then you don't have to do uh you know lip syncing, and they would go through and they would storyboard action scenes and they would give the writers these big thick notebooks of action scenes and say, when you're writing a script, go through and call out specific um action scenes that we've got animated, and we will use them again. I wrote one episode of uh Bravestar, and I've never seen any other episode of Bravestar, and I'm sure it's a good show. I know people who worked on it. I I am not putting it down, but I know if I see a second episode of Bravestar, I'm gonna realize how much same as animation was in my episode, and it's going to disappoint me. So I only have watched my episode of Brave Star, and I'm going, hey, pretty good. You know, I like that.

James Duke:All right, I'm gonna tell you, I'm gonna tell you how pathetic I am, uh, Buzz. I watched way too much television when I was a kid. I can sing to you the Brave Star theme song. Um, and my my favorite thing about Brave Star. I'm not gonna, I'm gonna, I'm going to save you and the audience that, but but but the theme song um was all his animal powers, right? So eyes like a hawk, sorry, brave star, eyes like a hawk, ears like a wolf, brave star, strength of a bear. And then the one that always made me laugh, even as a kid, is he it wasn't the speed of a cheetah, it was the speed of a puma.

SPEAKER_01:And I I wondered why did they go with the puma?

SPEAKER_00:Might have been hopes for a tie-in. I mean, there was a puma brand uh shoe at that end. Anyway, that's there, that's my brave heart connection.

James Duke:Um, yeah. So when you so here you are writing for film uh filmation, and um man, yeah, boy, they turned out a lot. What was your first professional screenwriting credit that that aired?

SPEAKER_00:Ah, geez. Um, it would have been a segment of a show called Tarzan and the Super Seven, which no matter how you count the configuration, does not equal seven. Um, they they had their Tarzan show and they edited it down from a half hour to a 20-minute episode so they could add other segments. It was like an hour-long show, and I think um Space Academy premiered on this too. I'm not a hundred percent sure. Space Academy might have been it, might have been Space Academy or it might have been the serial version of Jason of Star Command, because they did a a uh live action serial. In any case, um I wrote um a Freedom, at least one Freedom Force episode. I wrote a couple of um Manta and Moray and Super Stretch and Microwoman episodes. I wrote a Webwoman episode, and we would get sued like nobody's business because Marvel and DC, once they found out we were doing these shows, they double teamed us, and they sued um Webwoman, claiming that uh it we were infringing on Spider-Man and Black Widow, and they actually had a point because her original costume looked a lot like Black Widow's costume at that time, so we had to change it from a logical looking quasi-commando outfit into this ridiculous fishnet stockings and tights thing that that was on the air. Um super that's so much more acceptable to put the woman in the fishnet. Exactly. Yeah, super stretch and micro woman got sued by DC because they said we were we were emulating uh the Adam and the elongated man. I totally remembered that.

James Duke:That they they I think they would show that on some other one out later on. I totally remember that show. Super stretch and micro, yeah.

SPEAKER_00:And and Marvel sued because they said uh you're you're you're ripping off Ant Man and Mr. Fantastic.

SPEAKER_03:Yeah.

SPEAKER_00:Um Marvel and DC both sued over Manton Moray. Marvel saying you're you're ripping off Namor, and DC saying you're ripping off Aquaman. And I told Lou, I said, for heaven's sakes, just tell Marvel and DC's lawyers, decide which one of you is getting ripped off, and we'll we'll take the the winner on.

James Duke:Now, now help help our audience understand. So back back then, I mean it's still today, but they do it differently now. Because, but um, if I remember correctly, and please correct where I'm where I'm not remembering right, but back then the the networks were required uh to put X amount of, I don't know if it was through the FCC or something, but they were required to put uh X amount of hours on television that were considered educational or for children. Exactly. And so the Saturday morning, so what so they would basically just hire companies like Hanna Barbera and Filmation to just create blocks of TV for them. So the reason why, like you're talking about, the reason why there were so many different characters is that Filmation would literally have four hours on CBS that they had to fill, and they would just rotate through characters that worked or didn't work. And it but but literally they had a block they had to fill. Oh yeah, yeah, that they were contracted by by CBS, ABC, or MBC. And they and they had all these different shows on all these different characters, and some hit and some didn't, and they would just kind of keep rotating through. But it was the networks didn't produce it themselves because they didn't care, they just were trying to fulfill their requirement. Is that right?

SPEAKER_00:Almost never did a network uh directly produce a show for for Saturday morning. There are a few exceptions, but they're not you know significant. Uh they they would certainly put pressure on a studio to do a certain type of program a certain type of way, but they they uh they rarely got their hands dirty actually doing the production themselves. Uh, we had, as I said, we had a real problem at filmation with just getting sued by people left and right. And one one of the examples was kind of heartbreaking to me. There used to be a comic strip called Tumbleweeds done by a guy named TK Ryan. And Tumbleweeds was just this really funny, really witty takeoff on um uh old west tropes. I mean, it was just it was every old west cliche parody you could imagine. And I I loved the comic strip, I was a big fan of it, and Lou sold a show to NBC called uh The Fabulous Funnies, which to be perfectly honest, was neither. And most of the stuff he had was like really old. I mean, it was like the Cats and Jammer Kids, Alley Oop, um, Nancy and Sluggo. Um, he got Broomhilda, and he also got he said, um tumbleweeds. And when I found out he had tumbleweeds, I I immediately campaigned. I said, I love this comic strip. Let me do it, let me write it. And I figured out a way of including the Native American characters into it because even at that time, um Lou would not hire someone to do an ethnic voice if they weren't that ethnic person. And about the only ethnic actor anybody knew in Hollywood at that time for Native Americans was um Iron Eyes Cody, which, if you know, was not a Native American, he was Sicilian descent, but he really loved the Native American people. He he became, you know, um, I won't say he was delusional, but he certainly embraced that culture. He championed for their rights and protection. And as I recall, at least two tribes formally adopted him as a blood brother and and to the tribe because of all the work he had done. But yeah, he was Sicilian, he was not um, he was not Native American, but he would be the only person that they could afford if they were going to do a Native American voice, and uh so they didn't want to have any Native American characters in Tumbleweed. And I said, Well, you've got two characters in the strip who are mute, they never say anything. You got this big guy, Bacolic Buffalo, and then you've got uh this little scrawny guy called Lots of Luck, and Lots of Luck would write notes and hand them to people in the strip. And once they realized, well, Buzz knows this and he can include the Native American characters in a way that we don't have to hire an extra voice, they gave me all the scripts to write. So I I was I was in Hog Heaven. I was gonna do at least four scripts for Tumbleweeds, and um we I I had written the first two scripts. The first episode had been animated. Uh when the show premiered, it was on um that morning, and he his tumbleweeds face was in the lineup. And Monday we got a call from TK Ryan's lawyer saying, Mr. Ryan really liked the episode. He's just wondering why you never got a contract with him. Because apparently, what had happened, um, Lou's lawyer had contacted Ryan and said, We'd like to do uh a Tumbleweeds animated show. And Ryan said, Okay, send me a storyboard so I can see what you're gonna do with it, and if I like it, I'll say yes. And the lawyer just went, he said yes, and never followed up. And so we we we animated an air to show that we had no rights to, um, and and that was a disappointment because I was I was having fun doing it, but um, you know, it it got yanked.

James Duke:So man, that's yeah, that's I I can't imagine doing all that work, and then but but it was a little bit of the wild, wild west back then, I guess. Yeah, because they had to put out so much and they were so used to getting sued by Marvel and DC probably that weren't that worried. You so your your career is pretty varied in terms of uh mentioned that earlier, you've written on So many shows. Can you explain what the process was for writing for? I mean, because literally, like, I mean, Alvin and the Chipmunk, Dungeons and Dragons, Scooby-Doo, Thundar the Barbarian, Heathcliff, of course, G.I. Joe, Mr. T. I love, I remember that show. Oh my gosh. Of course, Transformers, G.I. Joe. Um, were what was the process for writing animation back then? Were you working for filmation, or were um uh were you uh writing stuff on spec? Would you get called and say, hey, we need uh what uh as opposed to say a writer's room where you would sit around with a bunch of writers, how did it work? Did it vary from show to show, or or what was the process like in writing for all these TV shows? Well, the answer to those questions is yes.

SPEAKER_00:It um every show that I got involved in, I got involved in a different way. And um nonetheless, there was a great deal of overlap. Um, I worked two years at filmation and then they had a dry spell and they couldn't keep as many people on for hiatus as they wanted to. And so they turned me loose and they said, uh, stay in touch. We'll want to hire you back when we we go back in production. And I was trying to find work, you know, to keep uh, you know, the roof over our heads, and someone said, Well, why don't you try um Ruby Spears? They're a struggling young company and they're trying to get scripts written. So I you know contacted Ruby Spears. I forget who the story editor was at the time, but um I had uh they gave me the the show Bible on um I think it was Dingbat in the Creeps. I may be mistaken. It might have been Mighty Man and Yuck. Might have been Mighty Man and Yuck. But in any case, they gave me a Bible that said, Come up with some ideas. And so I came up with a couple of ideas and they said, Okay, this one will work. And they bought it from me, and I wrote it as a freelance script. And they said, You got any more? And I said, Well, give me give me a chance, and I wrote a few more. I think I wrote around three or four as a freelancer, and then they said, Well, you know, we're gonna be gearing up soon for regular season production. Do you want to come on board as a a you know, staff writer? So I agreed, and then Lou called me and said, uh, you know, I'd like to have you come back. And I said, Well, you know, Ruby Spears is offering me this much money. Can you meet it or beat it? And he said, No, I can't do that. I'm sorry, you know, best of luck. And he, you know, let me go, which is unfortunately for Lou what happened with a lot of his talent. Um, you know, they used to say filmation was where, you know, it was for people on their way in or their way out of the industry. It was it was either newbies who were learning the ropes and who would soon go on to bigger and better things, or it was old guys who were burned out, and that was the best they could do. Um, anyway, I I ended up on staff at uh Ruby Spears. I think the first staff writing I did was for Mighty Man and Yuck. Uh, I met Steve Gerber there because they brought Steve Gerber on board. Steve was in the middle of his lawsuit against uh Marvel Comics. He was trying to claim ownership of Howard the Duck. And Steve was doing a comic book called Destroyer Duck, which was um uh one of the earliest self-funded independent black and white comics. Excuse me, it wasn't black and white, it was full color, my goodness. I'm I'm misremembering here. It was a full color comic, and uh he was using that to fund his lawsuit against Marvel. And Steve, and I'm not I'm not speaking ill of him here because Steve and I were great friends, but the truth is Steve frequently had deadline problems, and on more than one occasion, he would call friends up and say, Can you help me out and you know, move things down the block? And he he said to me at one point, he said, I've got to finish the script for this issue. And we've got Jack Kirby, you know, drawing it. I need you to write a two-page fight scene for Jack to draw while I'm finishing the rest of the script. Um, you know, and so I go, okay, sure. I write a two-page fight scene, and uh I I tell people my first job in comics, I was I I wrote I wrote something that Jack Kirby illustrated, and it's been downhill ever since. But no, I I I wrote this thing for Jack, uh, didn't meet Jack at that time, but I wrote it for him. And then um, excuse me, strike that. I had met Jack at that time. I had met Jack. I'll tell that story in a moment. Okay, in any case, I'm I'm on staff. Uh we're developing ideas, we're writing scripts. Um somebody came up with the idea of Thundar the Barbarian. Just just somebody, I love it. Well, here's the thing. Um Joe would say very concretely, I came up with the idea. And I believe Joe probably had the germ of the idea. Steve would argue, no, I came up with the the general shape of it. Once we decided to do a barbarian in the future story, I crafted it as to what it would be with input from people like Marty Pasco and Marc Evanier, who who all had been in the room when the development was going on. Marty was the guy who contributed the name Ookla for Yes, Ookla, yes. Yeah, because because when Marty was in Paris, um young Parisians kept asking him, well, where do I get an OUCla shirt? U-C-L-A.

SPEAKER_01:That's the origin for Ookla. I had no idea.

SPEAKER_00:And um uh uh I was I was there, but I wasn't involved in the immediate genesis of Thundar. But once the the general idea was developed, and once they got to go ahead to do more formal development on it, uh Joe had a big meeting, all the writers came in, the the heads of the uh storyboard and design departments came in, and um we're we're discussing the show, and Steve said, I know a guy who would be perfect, you know, to design the show. He said, Let me let me call him and I'll bring him in and we'll you know get him involved. And so we had a meeting scheduled for the next week or a few days later, uh, a big meeting where we were all going to get together and just hammer out all the details of the show. So uh when the meeting comes around, I come in and into the conference room, and John Dorman, who was the head of the storyboard department, was already in the conference room and he's talking to this little old man. And I tell people, uh, you heard the expression that somebody's eyes were twinkling. This is the only person I've ever met whose eyes literally were twinkling all the time. I mean, just you could see like ideas sparking behind them. And so I come in and John doesn't introduce us, you know, to each other. And I figure, well, you know, when the meeting starts, we'll probably all go around the table and introduce ourselves. So I didn't get, you know, uh, I didn't get uh, you know, concerned about it. And gradually, one by one, everybody drifts in until finally uh Joe shows up and we sit down and there's no introductions. Everybody just, you know, starts contributing to the meeting. And the little old guy and I struck it off really well because I could tell right away he had great ideas. He was plussing stuff, he was developing, you know, just verbally developing stuff and showing how you could expand things and this and that. And uh I recognized, wow, this this is gonna be a really cool show working on it with this guy because he's he's really on top of things. And so the meeting goes on for about an hour or so, and then uh, you know, Joe says, Okay, well, the the writers will go and start developing scripts, and uh, you know, you guys in the art department, you go start designing stuff, and we'll meet again next week and you know continue from there. So I went into Steve's room after Steve's office after the meeting, and I said, you know, I I'm really fired up about this show. It sounds like it's gonna be tons of fun. I said, but who was the little old guy in the room? Nobody ever introduced us. And Steve said, That was Jack Kirby. Wow. And if I had known it was Jack Kirby, my contribution to the meeting would have been I, you know, this was back before the internet, and I I knew Jack Kirby by reputation, had no idea what he looked like.

James Duke:So Jack Kirby is somewhat responsible for the look and design of Thundar as well.

SPEAKER_00:He is responsible for like 90% of the design. Uh Alex Toth.

James Duke:I had no idea.

SPEAKER_00:Alex Toth and Doug Wilde did the initial designs on the characters. And uh you can you can find their stuff online, you'll look at it, and and both of them did Thundar, Ariel, and Ukla in their personal styles, but you know, you can tell it's the same character. Jack came on board and started doing all the incidental characters, all the backgrounds, all the the supporting characters and weapons and vehicles and everything else. We did a a um script where in one scene um I had I had written that uh Ariel, Ukla, and Thundar cross a river on a raft ferry. You know, you've you've seen these in Western movies. Somebody makes a raft, they've got a rope strung across the river, and you just pull your way across. And so I describe a raft ferry, and Jack designs it. He comes back with the deck of an aircraft carrier on top of a raft of sequoia logs. And I took one look at this and I said, no, we are not wasting this as a throwaway background detail. I'm I am building an entire script around this this uh this vehicle here, and that became the genesis of a script called Treasure of the Mocks. Wow. Because uh, I put a pirate captain and her crew on it, and they're looking for the mock treasure, and they're going up and down the river. I mean, it was you know, Jack did this all the time. You'd ask him, uh, yeah, give give the guy, you know, some weird weapon, and he would come back with something that was just like mind-boggling, and he just knocked this stuff off. I mean, it was just astonishing. Um, in any case, Ruby Spears, for about a three-year period, had what was widely regarded as the best story department in the business. And I'm not saying this to brag uh because I was part of it, but we just had top-notch people. We had uh Steve Gerber as story editor. There was myself, there's Gary Greenfield, um Norman Maurer. I mean, there was just a lot, excuse me, not Norman Maurer, Norman was a director, uh, Michael Maurer, his son. Um we just had a lot of really good people working there, Jack Anyart.

James Duke:Um and you guys would all do multiple shows. So when you say this when you say the story department, uh just give us a rough idea. How many shows was that story compart story department contributing to?

SPEAKER_00:It depended on it depended upon the season because some seasons we would have shows that might have three different segments, and so instead of 13 episodes, you're really writing 39 segments because each one was independent of one another. Um, other show, other seasons we might have only two shows on the air, and you'd only do a handful of of episodes.

James Duke:Um, like you wouldn't, so uh I'm trying to remember. Was Thundor a 21, 22-minute show, or was it like an 11 to 11 minute show?

SPEAKER_00:It was it was uh a half hour show, it was in a half hour slot. It may have gotten trimmed down at some point and reruns so they could squeeze an extra public service announcement in or something like that. But it was it was always meant as a half-hour show when we were writing it.

James Duke:Okay, and you would break it out as uh with commercials, would that be like a five-act? Yeah, yeah. Were all your shows written in five acts? Uh no, three acts, three acts. You would do three, so you you wouldn't cons consider them between each commercial break, you would just be each there were only two commercial breaks.

SPEAKER_00:Um I seem to recall that we had three commercial breaks. I know definitely in the Sunbow material we had three commercial two commercial breaks, three acts, two commercial breaks separating the acts.

James Duke:Okay, okay.

SPEAKER_00:Um, I I now you got me wondering. I can't remember if Thundar was two acts separated by a commercial or if it was uh three acts separated by commercials. But basically, you knew you had only X amount of time to tell a story. And with animation writing, at that time we were doing what was called directing on paper, where the writer would break the scene down for the storyboard department, literally movement by movement. Uh, camera goes in, camera comes out, the this character does that, uh, uh and and call every shot close up on this, far angle. And you literally had to visualize the entire story in your head and and break it down for the the storyboard department. So our scripts would be twice as long as a uh live action script of similar length. If you did a um half-hour action adventure show in live action, it would have run about 22, 24 pages at that time. Thundar scripts typically ran about 44 pages.

James Duke:Wow. And and explain to our audience what was the animation process back then? Like how long from the by the time you turned in a script to the time it aired on television, what was the what was the time um that took?

SPEAKER_00:When when all cylinders were firing smoothly, we could get a show back in six weeks' time.

James Duke:Oh wow, six weeks. Okay.

SPEAKER_00:But this means we already had a lot of um same as animation, even in Thundar, you'll notice they jump over the same tree every episode.

SPEAKER_03:Yes.

SPEAKER_00:Uh, we had a lot of same as animation. We had a lot of of stock animation that we could reuse again and again. Um we had a good design team that could uh you know design characters, we had a great storyboard department. I can't I cannot overemphasize John Dorman ran one of the best storyboard departments I've ever seen anywhere. And and John John was a wild man. Let me explain this. I mean, it's it's when you when you realize how good the stuff was and you realize how chaotic the office, the the storyboard department was. But uh Jim Woodring, who is is now famous as a um you know alternate comics guy, you know, he does the the Frank books. Uh Jim Woodring was a friend of John's, and he and he worked with John in the storyboard department. We had guys like Kurt Connor and Dan Reba, uh just tons of people working there. And I was one of the few writers who actually went down and talked with the storyboard artists and found out from them what made a script good for them. Because a lot of times people would write stuff and then the storyboard artists are going, Oh crap, how are we gonna how are we gonna draw this? How will we depict it? Um, and I went down and I would say, well, what what do you guys need? What makes your job easier? And they would give me advice. Yeah, write scenes that we can do this instead of you know a more difficult and cumbersome way of doing things. Um I'll I'll jump ahead a little bit. I'll tell you a story about um a show called TurboTene.

SPEAKER_01:Yes, TurboTeen.

SPEAKER_00:I totally I I dodged the bullet on that one.

James Duke:I I was on Turbo Teen for all the 15 minutes and and Joe just so people who don't know, and I'm sure there's some people out there, I know a couple of friends of mine that that we joke about TurboTene. TurboTeen was uh literally a show about a teenage boy who would transform, was it because of waters? I can't remember what he would transform into a a race car, basically. And uh yeah, very interesting concept.

SPEAKER_00:I I this actually the the the turbo teen story actually tries ties into Transformers, but specifically for John. Uh I went over to see him one time for lunch, and he and the storyboard department were just sitting there glowering. And um I'll I'll clean up the language here a little bit, uh, and I won't mention the name of the person responsible, but John went Joe Blow, and they all started pounding their desk, you know. Joe Blow had written a turboteen script where turboteen as a car climbs up on a high diving board, jumps up and down on the board as a car, executes a jack knife, dives into the pool, swims over to a rowboat in the pool as a car, climbs into the rowboat as a car, and they were expected to draw this. And that is why they were cursing Joe Blow for having written such a script. Um because nothing had been drawn like that before.

James Duke:So everything.

SPEAKER_00:I gotta I gotta say, uh John, I I I loved him like a Brother, he was one of the original wild men of animation. I mean, he was he was bonkers, I gotta be honest. But he was brilliant, he did great storyboards. Um, but but he and his crew were frequently chemically enhanced, and I think for shows like TurboTene, that was a necessity.

SPEAKER_01:That was a necessity for Turbo Teen.

SPEAKER_00:I mean, even as a kid, I'm watching TurboTene going, this is ridiculous. All right. Some of the episodes are on YouTube, and I I I invite people to try to watch an entire one because you get about like five minutes into it, and you're going, nothing in this makes any sense at all. Yes, thinking up.

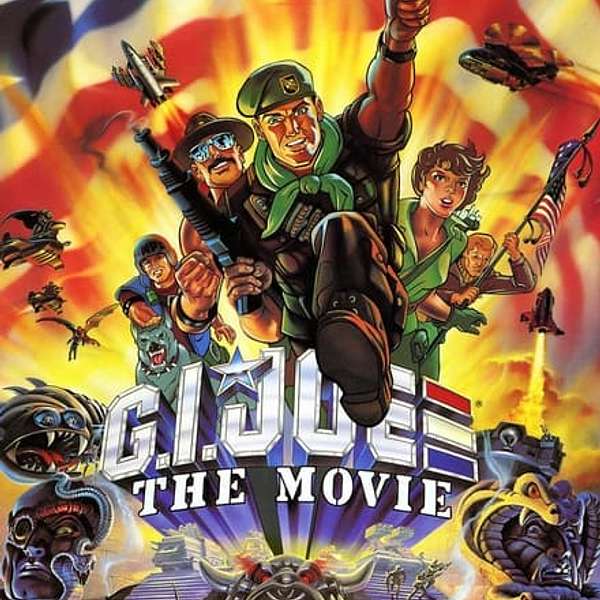

James Duke:And I and I remember thinking of that as like a 10-year-old or however it was I was, yeah. Um, okay, you've done so many shows that I love. Um, I mean Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Mr. Alvin the Chipmunks. So there was this um uh but okay, so there is this transformational kind of moment in the 80s. Uh and I know you know so much of the backstory of all this stuff because you were part of it. That's why I want to I want to pick your brain on this. And there's been some now, there's been some documentaries, and there's been some stuff that's kind of come out. So I'd love to just hear your perspective. So Transformers, so for me, it was like 1A, 1B was my favorite shows were Transformers and G.I. Joe, and they were back-to-back uh uh weekdays. And I you know memorized half the episodes of all of them because you know, back then they just went on repeat. And so um uh for people who are familiar with the Transformers, they decided to make a movie. And you know, back they were all, and just a reminder, all cartoons are back back then and even now, but they're all about selling toys, right? They're all about moving merchandise. And so Transformers wanted to they make a movie, and uh I've I've watched a little documentary on the making of it, which is hilarious because the director, I don't know if you've seen it, Buzz, but the director of the Transformers, the movie, uh, is like this Japanese guy, and he um like to him, it was like a paycheck, and he does not understand, even in the documentary, you can tell why am I being interviewed about this stupid movie that I did that in his mind wasn't even that good. And you can just tell that he is like, why am I? But you know, it's a all these shows are so beloved now, my people. Um, well, so there was a controversy for us fans. I was there opening weekend, I forced my sister, my older sister, to take me to the movie theater and watch the Transformers movie, and we all were shocked when Optimus Prime dies. Spoiler alert alert there. And um, and literally, like all of us kids are why why would you do that? And and the Transformers show just bombs after that. It just has a huge effect on it because everyone's like, why would you do that? So, in the meantime, I know that G.I. Joe is talking about making a movie, and then they see the response. So, take us back to because you were connected to all these people. So um, when the Transformers movie came out, so my first question to you is when the was there already talk of doing the GI Joe movie before the Transformers movie came out? Yes, and and and talk a little bit about uh so that's the thing too. Yeah, you're not you're you're the writer of the GI Joe movie, but your credit, and you can tell that story later too. Your credit doesn't necessarily reflect that, but you're the writer of the GI Joe. So talk a little bit about the connection between the Transformers movie and the G.I. Joe movie, and then I'd love to talk to you about the specifications.

SPEAKER_00:Well, if if you don't mind, we're gonna backtrack to uh Ruby Spears, because Ruby Spears is where the first domino starts falling that leads to Transformers and GI Joe. Um, what had happened was in the 1960s there was a show called Hot Wheels, and uh a parents group complained to the FCC about it, saying it was just a half-hour commercial for the toy. The FCC agreed and they issued a ban that there could be no toy-based cartoon shows. You could have a cartoon based on a literary property, but you couldn't have one based on a toy. Um jump ahead about 15 years, and the Smurfs reach American shores as these little tchotchkis, keychains, good luck charms, stuff like that. They were popular.

James Duke:There was a woman at my there was a woman at my church who had an entire root, an entire room in her house of little smurf figures. It was crazy. Yeah, they were huge.

SPEAKER_00:Nobody in America knew their origin, nobody knew where and how they were created. They were they were actually called, I think, strumps or something like that. They were a Belgian comic book. But the toys hit America and they boom, big, huge, profitable thing. And I think it was NBC said, gosh, if only we could do a a Smurfs cartoon show. And someone said, Well, it's based on a Belgian comic book. And they said, Oh, really? So they put the show into production. The FCC goes, You can't do that. And they say, Oh no, no, look, Belgian comic book. See, it originated here. The FCC goes, Okay, all right, fine. You know, you're allowed to do it. So now other people are looking at their properties, and the strawberry shortcake people say, Well, does greeting cards count as literary property? And the FCC goes, Well, printed on paper, yeah, okay, sure. They count as printed property. Well, all right, now we got strawberry shortcake. So they do the strawberry shortcake series. Um, and at that point, Mattel and Hasbro both go, oh, all it takes is a comic book. So Mattel approaches DC and they do the He-Man Masters of the Universe comic, a three-part uh mini-series which bears no resemblance at all to the show that got on the air. But at least at least let them say we've we've got a comic book it's based on Marvel. Um uh Hasbro went to Marvel, they got Larry Hama to create the G.I. Joe series for him at Marvel, the comic. I forget who the uh team was behind Transformers, but they got Transformers going. While all this is happening, Hasbro is also coming out to Los Angeles and talking with every animation company because the end game is to get a Transformers and G.I. Joe TV series on the air. And I was at the time the giant robot bug, you might say, because every studio I work for, I was championing, you know, we got to do a giant robot show. They're they're big in Japan, they've they've got huge followings. We've, you know, this is something kids will like giant robots. And everybody buzz your nuts, shut up, go away. So, anyway, Joe calls us into a meeting, Joe Ruby, and the Hasbro guys are there, and they've got this suitcase, and they open it up, and it is filled with transformers because they had they had bought the licensing rights to like three or four lines of transforming toys in Japan. And they were gonna mix and match them, and they were gonna rename them and all this stuff, and they just had this suitcase full of transforming robot toys. And I'm sitting there trying to keep from bursting out with excitement, you know, and they're talking with Joe. And uh in the end, they, you know, they the meeting ends, they close the suitcase, they walk off with it, and they are barely out of the building when I say to Joe, we have got to do this show. It is gonna be huge, it's gonna be great, it's it's gonna be tremendous. You have got to get this show. And Joe goes, Nah, I got a better idea. We're gonna do a show about a teenage boy who turns into a car. And uh, as I said, I I lasted about 15 minutes on that show because when when Joe got a Bible developed for it, he called us in for a writer's meeting, he gave us all copies of the Bible. He said, Go back, read the the Bible, and then start developing ideas. I got about halfway through the Bible, I tossed it in the trash can, I came back to Joe's office and I said, Joe, I'll develop ideas for you, but you got to explain a few things to me. If the kid is a car and they take the wheels off, if he turns back into a kid, is he missing his hands and feet? If the kid is a car and they take the battery out, if he turns back into a kid, is he uh missing his heart? If the kid is a car and they put a suitcase in the trunk, when he turns back into a kid and Joe goes, I'm putting you on another show. So anyway, we are gonna jump ahead now. Um we we uh Ruby Spears, as I said, had what was regarded at the time as the best story department. But for reasons not related to Joe and Ken, they lost that storyboard department in about like three weeks' time. They they had somebody who uh worked under them who managed to piss off the entire story department in in a single afternoon. And we were like all on our phones calling our agents, you know, get me a gig somewhere else. So this person basically hamstrung Ruby Spears by uh by alienating all the writers in it. But that's a different story for another time. Anyway, Steve Gerber ended up working on um Dungeons and Dragons. And I said to Steve, because we were friends, I said, Can I can I pitch to the show? And he said, Well, you know, they they seem to be closed. Um, I don't think you can get in, but you know, here's the person to contact. So I contacted them. And as a courtesy, because I, you know, had been working in the business, as a courtesy, they they let me come in and pitch a story, even though they were full at the time. And I pitched a story called Quest of the Skeleton Warrior, which personally I regard as a turning point in my own writing, because it was the first time I wrote about a villain who was a sympathetic villain who had an understandable motive. And um, you couldn't hate him. You you you go, well, we got to oppose him, but we understand perfectly well why he's doing this. He's not acting out of selfish, irrational reasons. And they liked it so much they made space for it in the uh original series, and um, I ended up, you know, being one of as a result, ended up being one of the writers on the original Dungeons and Dragons show.

James Duke:I remember that show really well because it was uh it was a late. Okay, so this is once again, this is what you get when you're someone like me who watched way too much. Is you could watch the pattern of the shows on Saturday morning, they would get the later in the Saturday morning it would go, it'd be more for older kids. Exactly. And um, and Dungeons and Dragons was on CBS, and it was their it was their late show that would, I think they paired it with uh the CBS um uh storybook time or whatever that eventually went over to ABC, uh, which was usually more uh tween, tween or teen themed or whatever. Dungeons and Dragons was good storytelling. It was also really good animation, with slightly different animation than uh even the earlier shows, too. The quality of animation and the quality of the of the writing, I distinctly it stood out to me as being. I don't know if I want to use the word more mature, but it definitely had a different uh quality to it. Would that be the correct way to say it?

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, absolutely. Um it it was a step up in quality all the way around. I was very happy to be involved in it. And as I said, it it I view it as a personal stepping stone where we move, I moved up as a writer, one notch in being able to write uh stories about characters who are a lot more complex than the typical you know supervillain that you encounter. Um, in any case, from there, I I freelanced around a little bit, and Steve ended up being hired to story edit uh the G.I. Joe TV series. Now, by this time, they had already done the two, uh, the first two uh mini-series that Ron Friedman had written. And uh, as I mentioned, Ron had a really good agent. The um animation writers were not protected by the writers' guilt. And as a result, uh there was no arbitration on final credits. And Ron, by the way, Ron is a wonderful guy. We're friends, I have no animosity, don't read anything into this, please. Yeah, Ron's agent got him a deal where if he wrote the first draft of something, his name would be the only name on the script. And you know, that agent did exactly what an agent is supposed to do, represented the best interests of his client. So I, you know, I I'm not blaming Ron for anything. So please don't read anything into that. But Ron wrote two, uh, the first two um miniseries, and I had seen them on television. And if you remember, these are the ones where you know tanks are split in half by jets swooping down and slicing them with their wingtips, and you've got sergeants giving orders to colonels and things like this. And when Steve got assigned the story editor position, I uh I contacted him, and Steve said, Well, you know, we've we've already staffed up, we've already got uh staff writers, and we're not taking freelance submissions right now. Um said, But if if I could, would you look at a couple of scripts and just give me some feedback? Because he knew I had been in the army for six years. So I looked at him and I gave them, you know, read them over and I made some notes and gave them back. And and basically I said, Well, you know, the the people writing these don't understand how a military unit functions on a day-to-day basis, they don't understand the chain of command. Uh, there's a lot of technical stuff that is really wildly wrong in what they're doing. Um, you know, and but you know, best of luck. I hope, you know, I hope it works because they got some interesting characters. Steve called Sunbow and said, uh, you know, we really ought to hire Buzz as a technical advisor because he was in the army, he knows animation, he, you know, he's a good person to have on this. And they said, Well, we don't have any budget for um a tech writer, I mean a tech um advisor, but we could squeeze in another staff writer. So I got I ended up becoming a staff writer and the de facto um assistant story editor almost immediately. And almost every script that was written there, you know, passed through my hands just to make sure you know there were no egregious mistakes in it.

James Duke:So would that have been would that have been what season would that have been?

SPEAKER_00:Because I know first season.

James Duke:So they did uh I'm trying to remember the mini-series. Was it like the weather machine one or something like that? So they did a couple of those, and then that's when you came in. Okay.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, and then I I was I was doing uh, I think we did 65 half hour episodes. We did not write down, we never wrote down to to our audience. And I think the reason Ruby Spears had a reputation of having the best story department was that we were we were striving to write up. And and frequently our stuff would be edited down by somebody, but we were always writing at a at a higher level than uh than the studios required.

James Duke:This was my I completely agree. This was my theory as a as a fan, right? So as a fan of the genre of animation that you were at at its peak, right? I I used to me the reason why transformers and G.I. Joe worked was because it worked at two different levels as opposed to He-Man. He-Man, which I also watched, He-Man uh worked at a toy level better than it worked as a show level. Um trans both both Transformers and G.I. Joe had something over He-Man, and that was their toy lines were super impressive, but and and diverse and really interesting, and you you could get really excited about the characters that they were creating in the toys. But then the shows themselves, separate from the toys, were just also fun and great to watch and engaging and had a depth of storytelling that was different. Did am I am I off base here?

SPEAKER_00:But you were absolutely right, because one of one of the blessings in disguise for GI Joe was that when Marvel got the gig to do the G.I. Joe comic book, they handed it over to Larry Hama and they basically took their hands off. They just went, Yeah, this is this is just bread and butter money for us. You know, we're not expecting anything of it. Yeah, do whatever you want. And uh ironically, I think there was another show. Um uh not uh something about gem, not not our gem, but uh Amherst or something like that. There was another uh mini-series that Marvel did with um a female magic character in it that was like really well written, and it was because, yeah, nobody's paying attention. It's this is just uh a side gig, it's not our characters, we don't care. They hand it to Larry, and Larry also was a military vet, and Larry brought a level of sensibility to it that would not have gotten there with any other writer. And Larry was also an artist, so that he could he could block these stories out, he could show how they should be done. And Larry just did a great job with the the G.I. Joe comic book. He also wrote the character bios that appeared on the backs of the cards. Oh, yeah. What you see on the back of the card is about one-third of the actual bio that that uh Larry would write. We lucked out because Hasbro sent the full bios to us in in um the show Bible. And so we had the these insights onto this wide diversity of characters that Larry had created. Then, on top of that, we're bringing our own sense of. Into it, our own experiences. Um, and everybody um everybody had a chance to use their own voice. We we had a wide diversity of episodes because we had a wide diversity of writers. We had people with different interests, different points of view. Once we got the series underway, um, we had Transformers going 65 episodes, we had G.I. Joe going 65 episodes, we had at least one other show we were doing, which I think was a weekend show that was doing like 13 episodes. My little pony got introduced at some point in the proceedings. Wow. We at one point, I remember we just totaled up the number of episodes that we had to do in a specific period of time, in like a one-year period of time. And I think it was something like 160 episodes. And we were writing these things fast. Uh, Flint Dilly, who was was more of a Transformers writer than a Joe writer, though we did write several Joe episodes. Flint said Flint said, you know, you fix the two things in a script that you hate the most, you put a bow tie on it and you kick it out the door. Um, every every day on on whatever series you were working on, every day a finished script had to go through the door. It, you know, I I likened it to a slow-moving freight train. Every day, every day an open boxcar came by you and you had to throw something into that boxcar. And um it had to be finished. If it was good, that was even better, but it had to be finished.

James Duke:Now, how many of you? So, out of a hundred, how many people are writing 160 plus episodes that year?

SPEAKER_00:It's it's hard to say because despite having a staff writing pool, we ended up using a lot of freelancers. I'm sure, yeah. We had a few guys get burned out. Yeah, we had a few people who were in production positions who would write scripts on the side as necessary. Um, frequently, if you were writing for one show, you would get called to do another one. I mean, I did I think my name is on three Transformer scripts, but I'm pretty sure I contributed to many more than that. I mean, at least at least six scripts I wrote or rewrote for Transformers. And my name isn't on them because my my point of view has always been if I'm a story editor, it it's not my place to put my name on somebody else's script.

James Duke:Yeah, but you're you're you're you had your hand on all of these scripts that were coming in and out as GI Joe, yeah. Story editor, yeah, for G.I. Joe. Yeah.

SPEAKER_00:Um, okay. So we we move ahead to the the year that they did the the My Little Pony Transformers in G.I. Joe movies. And Hasbro had struck a deal with Dino DiLorena's Productions that uh Dino promised um you will have three shows on Saturday and two shows on Sunday if you do an animated feature. So Hasbro thought, well, that's you know, we can live with that. We can that'll that'll be good enough. Hasbro wanted to introduce new characters to My Little Pony, Transformers, and G.I. Joe. And in retrospect, they recognized it's a mistake to introduce new characters in a feature film because people coming to the feature film are coming to see the characters they already know and love. They don't want to be introduced to a brand new bunch. Introduce new characters in a regular season.

James Duke:You don't we don't want you to just indiscriminately murder Ironhide, one of my my favorite. Don't even give him a chance to say a line and replace him with all the yes, yeah. Sorry, I'm not bitter or anything, I'm not bitter. It's been 30 years.

SPEAKER_00:So we, you know, you had the problem with G.I. Joe because uh I I think um Major Blood is in the opening credits and he's in the background in one scene, and that's it. And I had to fight tooth and nail to give shipwreck even a few lines. I mean, they were adamant they did not want to use shipwreck, and I just I just hammered him in as hard as I could because I wasn't gonna have a G.I. Joe movie that didn't have Shipwreck in it. But um, what had happened was they they had started three different scripts. Um I I forget I should have looked up who wrote the um My Little Pony script. But um Ron wrote the first draft of the well, Ron wrote a first draft for a G.I. Joe movie. And Hasbro through Sunbo contacted me and said, uh, you know, your story editor, um, would you first would you take a look at the My Little Pony script and give us some feedback? And basically, I just pointed out places where you know it would be good to have a song here about this sort of thing or that sort of thing. I mean, my my contribution was small. Um, I almost tied in My Little Pony with Transformers and G.I. Joe because at one point the little ponies are looking for help, and I wanted to have one of the little ponies fly to the Transformers base and ask them if they could help. And no, sorry. And then I wanted one to fly to G.I. Joe headquarters, and you know, um shipwreck would be on the rear porch of the barracks drinking beer, and this little pony flies up. Gee, mister, can you help us? And you know, he's just looking in shock, and then as the pony flies off, he throws the beer away and takes the the pledge not to drink again. Um and they shot that seed down. I I, you know, didn't get a chance to tie it in. But anyway, I I gave some feedback on the on the My Little Pony movie, but I really I no major contribution other than to suggest where songs could go. They gave me the G.I. Joe movie and said, Would you we want to talk with you about it, uh, read it on the airplane, flying to New York, and then we'll have a talk here in New York. So I get on the airplane, I read it on the airplane, I have the meeting with them in New York, and they say, Well, what do you think we can do to fix this? And I said, I'll be brutally honest, I would advise throwing it out and starting from scratch. And I'm not saying this is a slam against Ron, but it it just didn't capture what the series had evolved into. I think Ron was writing from what he remembered the show being when he was doing the miniseries. Uh, it had changed obviously by that point to something different.

James Duke:Now, did his version even address or deal with the origins of Cobra, like the eventual film?

SPEAKER_00:I cannot recall. Okay, I do know that one character he created, Nemesis Enforcer, was a big hit with everybody. And they thought, well, if we're gonna salvage anything, salvage salvage nemesis enforcer, the guy with the wings and the I love uh buzz.

James Duke:I love Nemesis Enforcer. I yeah, I that's like a term of endearment in my household, like with my kids. I know Nemesis and especially merited saying it.

SPEAKER_00:That's Ron and give Ron all the credit. It was it was a good imaginative character, and um uh he came up with it, but anyway, they they asked me to come up with um a script for it. Now, again, you gotta forgive me. I'm gonna backtrack a little bit here. After the first season of G.I. Joe, it was picked up for a second season of 25 episodes, uh, and then they would just rerun the previous season's episodes.

unknown:Yep.