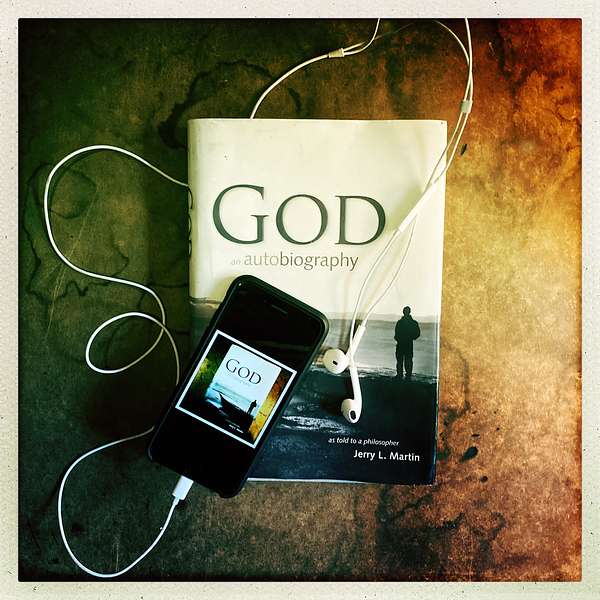

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

249. Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue – The Summons of Love and Life’s True Calling

In this wide-ranging conversation, Jerry and Abigail pick up where last week’s episode left off, turning from the idea of swadharma — one’s unique calling — to how that calling actually plays out in a real life.

Jerry reflects on the Bhagavad Gita’s teaching that it is better to follow your own duty, even imperfectly, than to live someone else’s well.

Abigail shares what it feels like when a fight “has her name on it,” telling the story of the battle to save Brooklyn College’s core curriculum and how that reluctant fight brought Jerry into her life.

They discuss the courage it takes to give up security for meaning, Jerry’s choice to twice walk away from tenure, and the role prayer plays in guiding his decisions. Abigail recalls a formative past-life memory of her death in 1930s Germany and how it shaped her lifelong commitment to confronting evil, writing about the nature of evil, and standing up against antisemitism.

The conversation turns to the “summons of love,” romance as co-constitutive with divine calling, and the serious work of keeping the romantic quest alive over a lifetime. Abigail explores the challenges of being a woman philosopher, the tension between femininity and academic culture, the dangers of free love, and the need for modesty and discernment.

Together they hold love, moral courage, and spiritual purpose in dialogue, seeking a way to live fully in history — with God as partner.

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

The Life Wisdom Project – Spiritual insights on living a wiser, more meaningful life.

From God to Jerry to You – Divine messages and breakthroughs for seekers.

Two Philosophers Wrestle With God – A dialogue on God, truth, and reason.

Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue – Love, faith, and divine presence in partnership.

What’s Your Spiritual Story – Real stories of people changed by encounters with God.

What’s On Our Mind – Reflections from Jerry and Scott on recent episodes.

What’s On Your Mind – Listener questions, divine answers, and open dialogue.

Stay Connected

- Share your story: questions@godandautobiography.com

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 00:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, a dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography as Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions and God had a lot to tell him.

Scott Langdon 01:13: I'm Scott Langdon, your host for this program, and this week on the program, Jerry and Abigail return for another intimate dialogue. On last week's episode, Jerry shared with us what God explained to him about swadharma, one's personal calling. What do we find when we look more deeply into our own personal calling, the calling only we ourselves can hear and heed? In this week's edition of Jerry and Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue, the husband and wife philosophical duo share personal stories and reflections on what it means to look deeply into our personal calling and how we relate to God and God to us in the discovery and execution of that calling. Here now are Jerry and Abigail. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:02: Hello sweetheart, this week we're kind of picking up where I left off with my last From God to Jerry to You recording. I was talking about swadharma. Dharma in India meant one's duty and the norms of social life largely, and one's duty often defined by role. You know family relations, you're a wife, you're a husband, you're a father, you owe something to your parents and so on, and to neighbors and so forth, or to stage of life. So the student has a different set of obligations than the retired person who has a kind of spiritual vocation at that point in life.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:54: And what drew my attention was the part of the Bhagavad Gita, section 35, that talks about swadharma. You add that little swa onto dharma and you get something like self-dharma, one's own personal calling. And the passage in the Bhagavad Gita says better to do your own calling, even if you don't do it well, than somebody else's calling, even if you would know how to do that better. But you've got to follow your own calling and I think in that recording that I did, I think I quoted you, sweetheart, because I can remember you sometimes say something like: this task has my name on it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 03:49: And I remember one context, it was this fight has my name on it. Somebody asked over dinner you were talking about what you're engaged in. You'd seen an injustice. You were trying to rally people to resist that injustice and the person at the meal asked you know, there are many injustices in the world. Why this one? Basically. And you just said this had my name on it, has my name on it. And what does that mean to you and how do you know? How does it come to you? Could it be kind of situational? It doesn't seem to be only a kind of deduction from your situation.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 04:33: What comes to mind to explain my saying such a thing is I tend to look behind me, hoping somebody else with a different name can do it better, or standing there, and if somebody needs to take up the fight, and to my chagrin, that other person isn't there. And I'm the only one there who knows about the fight and has some free arms. You know I could take it up if I put down some other stuff. Then I have to step forward. It's kind of… it's almost an invariably very reluctant perception. I remember the Brooklyn College fight to save the then beautiful core curriculum. Few colleges had it, we had it. It was something that allowed the entering student from the interesting multicultural borough of Brooklyn to get immersed in beautiful texts covering a wide range of fields and topics as the introduction to higher education. It was very important and it also acculturated our incoming students, who often came from ports all over the world. And there was a new president who wanted to replace it with a new curriculum focused on the borough of Brooklyn, which was the last thing our students needed to learn about. Usually they knew more than their teachers and it was not of general use.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 06:56: So I would have loved it if somebody else had been there to take up the cudgels, but there was only a professor in the history department and me. So you know we met at the grad center, discussed what we could begin to do to man the fight, if that's the right verb and also admitted that we both thought we would lose. And I asked my colleague do you pray? And she said daily. And I said good, because that's the only thing we got going for us. And we went out, you know, to carry out the fight, in the course of which I happened to meet you, Jerry, darling, and find love and happiness, but that wasn't why we entered the fight.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 07:58: Right, no, that was a happy circumstance. I still have the note from the day you called me in my office. I took notes about the issues and when I moved offices I thought, oh, I still have that note from Abigail's first call, and I now have it framed because it was a momentous day in my life, more than I realized, of course, at the moment and if you ask how it was that I came to be in a role such that you called me and I said, yes, I was running a small higher education nonprofit in Washington DC dedicated to issues of academic excellence and academic freedom and so forth, and someone suggested call Jerry Martin in Washington and I picked up the phone and we went from there. But if you ask how I got into that role, it's really kind of typical of how I've led my life, up until the God experience when it got a little more strange, you might say. But at any given moment I've thought what's the most valuable thing I can do with my life right now? I've twice given up secure positions, academic tenure once, tenure in the senior level of the civil service the second time.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 09:17: But in each case I thought, ah, there's something else I can do with my time that seems more important, more valuable, more meaningful to me, maybe in terms of my own priorities and values. And I often quote this, I don't know if it means anything to anybody else, but the line from TS Eliot where he says every moment is the moment of death and death is the moment of a summation of your life. This is what it comes to. You know you don't have more chances after that and every moment is the summation of your life. You're creating its meaning, and that doesn't mean you can't go to the seashore or the movies or, you know, enjoy a frolic of some kind, because that's also part of a total life. And when you're doing that at the right moments, restoring yourself, then that also is contributing. That's a perfectly fine thing to be doing at your moment of death, if it's part of this balanced life. But each time I would always ask is there something better, in the sense of not happier or more prosperous, but something like more meaningful, more important in the world? Not just more important to Jerry, but more important in the world in reality, of course, as perceived by me through my values and experience, and that's not a bad way to live life.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 10:50: Once I had the God call, then, of course, God is speaking to me, that's very different, and when I pray I often get this very distinctive answer, often in a voice, not always, sometimes before the prayer is over. I kind of know what the answer is and I think a lot of praying people have that experience. This is not unique to my more intense experience of having received a somewhat full-scale revelation, but any praying person, you pray and you kind of get an answer. You know after you pray what you're to do? And so that's one way to do it. But I've described my way. You've described what happens with the fight. It's a fight you don't like to fight. You rather prefer harmony. And everyone you know, let's all get along.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 11:47: Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 11:48: And have a good time together, just do our work. But if they're about to destroy something of immense value to these students, like this wonderful core curriculum is celebrated nationally, then you're going to stand up, even if it looks hopeless. But this swadharma conception is way more personal than that. And one thing that comes to mind in your life, sweetheart, is you had a kind of what presented itself as a kind of past life experience, and I sometimes feel you write in your column too often about anti-Semitism, but then I remember that vision of a past life experience that seemed to in part define your mission in life. Can you just say something about that experience?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 12:49: Sure, I don't now remember exactly when it came to me, funnily enough, and I don't concretely remember specific incidents that up to a certain point supported the vision, and once the vision had sort of locked in so that it became something I accepted, all those little experiences that pointed me toward it sort of sifted down and faded away from my memory. So it's an odd kind of constitutive, self-constituting memory with, you might say, a mind of its own. But the memory goes like this: I'm a young German Jewish woman in the early 1930s. Perhaps Hitler has just come to power. There aren't yet concentration camps and trucks are used. People are bundled into the backs of trucks which are then sealed and filled with carbon monoxide so that it's a rapid mass murder, but it's nothing like the murder factories that were set up later under the expert supervision of Eichmann, I guess Adolf Eichmann above all.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 14:39: Anyway, I was in hiding or semi-hiding, staying indoors, not venturing onto the street, with some other people who were with me, perhaps family members or friends, German Jews. Someone must have informed on us, because one day there was that heavy pounding on the door and in came some kind of military arm of the regime and without ceremony, walked us maybe halfway down the block and bundled us into the back of such a truck and sealed the truck and pumped it with carbon monoxide so that, without the ability to protest or much delay, we died. And my memory is more of leaving my body and rising up above it with curiosity to try to ascertain just how widespread this murderous hatred of Jews was. And for a while I was so high that I could see the curve of the planet, but then descended enough to get something like an answer to this question that I was curious to know the answer to. And I saw that it was almost planet-wide. It was very widespread, only having taken concrete form of a plan with an execution in Germany, not because Germany was worse about Jews than other countries, but because it had gone through certain economic, military and other crises. Its democracy was frail, relatively new, its social system, its currency very unstable, very weak, and so it was vulnerable to… it did not have internal resistance, and so it became the focal point for killing Jews. But it was not the only place where that could find support. Not at all. And looking at it, planetary-wide looking, I remember that I resolved to come back and fight it, and that's odd.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 17:51: I haven't been, you know, like Simon Wiesenthal or some other well-known Nazi hunters, engaged in that as a profession. But I have done what I could. My book, I was interested in the problem, philosophic problem, of evil. What is evil? Why does it attend human life? How deep is it? Discovered a bit to my surprise, that there isn't much material on it in the whole history of philosophy. They write about it as if it's the deficiency of good, it's some kind of a defect, whereas I knew it to be a very positive in the sense of internally strong, intelligent, motivated force, and that philosophers had done little about it, had little to say, although they have a love of wisdom and want to understand the constituents of human life. So I set out to write a book about it in which several chapters are devoted to the Nazi phenomenon, and so that's one thing I guess I've done. In the column I now write I often reference the problem of evil, but you know I'm not a well-known Nazi hunter or anything like that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 19:36: Yeah, but it has in some way defining your life mission. That may be too narrowing a term, but a kind of auspices almost of your life, a kind of backdrop, reality and sense of purposefulness. I mean something important to do, to the extent you can do it. It obviously does not crowd out other callings, because we were talking about this other fight that I was alluding to, some injustice that had been in the public press. It had nothing to do with anti-Semitism at all…

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 20:45: Another phrase you have used when we first fell in love, we set the context for that already. You called me and I fell in love with you on the phone and from that moment I had not yet laid eyes on you. I just lucked out that you were so good looking. But I fell in love with you sight unseen and from that moment on on the phone I was interested in no other woman. They all just dropped out. I was interested in one and only one woman, and then that's defined my life ever since. But at that moment, unfortunately I don't know, I would have been in bad shape had you not responded to my interest in you.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 21:27: But in fact you spoke. It disrupted your life totally. You're a professor in New York City, tenured great apartment, Upper East Side, the neighborhood you knew, and you lived your life. You know, your father was a professor in Manhattan and I took you out of all that. I took you out of all that. They took your apartment away, you know, because the rent, control and everything, if you're not living there full-time, they snatch it from you. It's totally disruptive. But in that context, you spoke to me of the necessity of responding to what you called the summons of love. The summons of love, and that's a striking phrase.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 22:19: It's a funny thing, I don’t know if other women friends with whom I've shared a lot of personal life, have that particular concept and I'm not sure how it got itself instilled in me, but I'm far from exemplary practitioner of the arts and drills of being Jewish, but I'm very… a friend of mine said I have the Jewish essence, I just don't have Jewish existence. Well, all right, but for me, part of the Jewish essence was contained in biblical narrative and I was early struck by the fact which forms an essential piece of the Bib;cal narrative, in the book of Genesis, each founder, each patriarch, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob each felt that he or knew that he could not go forward without the right woman at his side.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 23:50: Remind us it's Abraham and Sarah.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 23:52: Abraham and Sarah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 23:53: Isaac and who? Jacob and Rachel.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 23:57: Rebecca. Jacob and Rachel.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 24:00: The romance seemed to me who was sort of alert to those little phenomena. The romance seemed co-constitutive with the divine voice of their respective callings and I just noticed that, you know, a little girl wants to know what happens when you grow up. What am I supposed to do? Since I'm a girl, not a boy, and it seemed to me, I perceived early that these partners to the trio that founded God’s call to a covenant were loved women married to the patriarchs, who heard the call, And so it seemed to me that this heterosexual erotic adhesive was part of the highest part of spiritual calling that is grounded in spiritual experience, it doesn’t float upward to merge with the absolute, you could do that too, and I've tried sometimes. I'm not particularly good at mystical merger, but I did give it a go, but I thought no, no, no my particular angle on life seems to evolve out of and have a linear connection to the Jewish story, the biblical story and post-biblical story on the ground, on the horizontal, with God partnering the story, giving clues, sometimes intervening, but not replacing the story with some kind of strictly sealed-off intimacy that has a vertical prior dimension rather than this horizontal one.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 26:46: But how would you apply that to your first love? I always hate to let my mind go there, but your first love, which you've written about in your book Confessions of a Young Philosopher. Now the first love seems to have been a love, but doesn't quite fit the biblical model. And it doesn't fit what you and I now have. It did not seem, I don't know if you would have used the term the summons of love then in that relationship? Maybe you would have…

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 27:28: From my parents and the biblical prototypes I've referenced, I got the message that feminine experience is very serious, very consequential and significant in its own right. In the Anglo-American let's say broadly culture in which, being born here, I was raised, that did not seem to enter in in adolescence. Girls who could be tomboys, act like one of the gang and not overdo the feminine part were valued, and those ideas which I had picked up early were not entertained. Nobody spoke about them as positive. Femininity itself was, I don't know if anybody talked about it. There were novels you read. They had to do with big sex breakthrough, DH Lawrence, Hemingway, the earth moves, but they didn't value as such femininity and I didn't know where else to go to find it. But there were European women who modeled it in my period of growing up, so I knew it was real.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 29:20: Now, when I had this Fulbright grant to Paris, it was clear that the feminine was highly valued and in a sense I felt at home there for that reason, as many of my fellow Fulbright women did not. They felt out of place

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 29:44: But I recognized what was going on, though the myth, the French myth about Tristan Iseult, where they don't live in history, they live in impossible romance, was different from the biblical model, but it was part, it was at least a fraction of what I had grown up believing in, so that when I met this young Greek philosophy student and he went through some of the steps of courtship that I had known about from my childhood and these European women who modeled femininity for me, I responded.That he meant seduction, that seduction was dangerous, that he meant that he was a communist, that he had values that were antithetical to the commonly known ones.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 31:08: It was as if it started right and went off track. But by the time it went off track, I had been already something that couldn't happen to a young American girl: seduced, you know half with physical force, and I didn't know how I got there, but I knew it was intensely dangerous. At the same time, it contains some of the fragments of the ideal I had taken seriously, and he seemed, and perhaps did, for that season, which, in the French view is always, by that time, brief, there's a brief season for the stroke of lightning, for the sudden impact of violent, all-encompassing romance.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 32:14: So love comes and then quickly goes.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 32:18: Yes, it goes. In the model Tristan and Iseult, they both die. These medieval lovers, Dante and Beatrice, don't have any relationship on Earth. Romeo and Juliet both die. So these violent, all imperative, demanding romantic strokes of lightning are allowed to happen, but they are not allowed a historical future.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 33:04: In the French culture, this French erotic culture.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 33:08: And perhaps European romantic model has this in varying degrees. You know, you think of Dante. He doesn't marry Beatrice, they're both married elsewhere. They live, they will live together in heaven after they die. The English Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, they don't live, they don't have to face his parents, her parents. They don't have to negotiate with two families who are not getting along. They don't have to do real things, simply have an overwhelming passion for each other, which they both live to its demise, to its tragic ending. So on the one hand, I thought the Europeans are right to take romantic love with full seriousness, but they can't be right to make it unlivable in history. The Anglo-Americans that I knew of were wrong to deny that there is such a thing, though they do live pragmatically on the plane of real life. So I found myself neither in one cultural milieu comfortable nor in the other, and sort of dancing on the head of a pin in the aftermath of this romantic...

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 34:58: So it was an unsuccessful love, in the sense that he was not really worthy of you, is how I would see it. And you, of course, moved on because you're not a fool. You were in love, you felt all of that, but you're not a fool either. And you were back in the States at a certain point. You didn't hear from him again. There's a little more to the story than that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 35:41: One of the things you've often said, sweetheart, is that you did not become cynical. You didn't think, ah, this love stuff you know, you've just given a kind of critique of this French version of romantic love that's just a bolt from the sky and can't be lived out in real time, in life. That just sounds like, oh well, big mistake, people, men are all cads, you know that kind of thing. And just give that up. Or you settle down. You just think, oh well, I'll just marry a guy who will bring in an income or maybe be an appropriate father for my children, or something like that. You just make a pragmatic decision. But you've always told me that you kept the romantic quest alive in your own life even as years went by.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 37:00: Yes, well, I'm both a philosoph, a philosopher, a person on a quest to understand life, to perceive and get hold of as much wisdom as life allows, a real life allows, and at the same time a woman. So that combo doesn't have a lot of recognition. There are people like, say, Augustine is a classic case of a confession where it's a man taking his life as the occasion for the research into the meaning of life and he won't quit until he's got an answer. And for him the answer will be to become a founding father of Christianity. So I also wanted an answer to the question of the meaning of life. But I was, and I am a woman. So the question would have a very different context, the context of real life, and in that context, if the person asking the question, the Augustinian question: what is life all about? Never mind, you know what I could do to make a dollar, what I could do to get by, what I could do to cope with all my weaknesses and mask them adequately and become a success. Those were not the defining questions for my life. The defining question was and is what is life, a human life, about? How do you best live a human life, wherever you're positioned to live it?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 39:07: And the one asking the question in this case was not a man like Augustine, was more of a woman like me, and so the constraints, the disadvantages, the ladder to climb was quite different from his. And one of the differences was, if I was motivated and to some extent perhaps gifted, to be a philosopher, to work in that field, that wonderful love of wisdom field, how did a woman proceed? And the answer I was given in the department which seemed most interesting to me at Penn State was you proceed as if you weren't a woman and you need to destroy your femininity. That was said to me openly by the Straussian, who was perhaps the most interesting member of that department, and I didn't resent his saying what he obviously believed. But I couldn't honestly agree with him because I had these other models, the European women who were not philosophers but were good at being women, as if there was an art to it. They were good at it. I knew you could flunk womanhood 101, but they didn't. And then this European model and also, in a very different register, biblical model, a woman was very important in life if she played it right, if she played her hand that she was dealt right. The very feminine presence could be of utmost importance.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 41:29: But I didn't have a way of putting those ingredients together. It was not.. There was no model that put it all together. There was Jane Austen, but what she was supposed to do with that was make an advantageous marriage or not, remain a spinster. And I don't know. There was the Bronte sisters, but that seemed a rather special case. They didn’t pose the question in the same way and you couldn’t replicate their particular romantic lives. I didn’t see someone who had posed the question as worth posing and then had gone forward to try one thing after another.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 42:31: And when the feminists came along at a later point in American and European history, what I knew of their personal lives, their personal lives were a disaster. Their personal lives were flops. I mean, I won't go into gossip, but I knew enough of these women to know, no, they've got a masthead and they've run up a flag, but they haven't solved it themselves. And de Beauvoir, who wrote the second wave classic, The Second Sex, she only said that a woman was a sort of social… femininity was a social contrivance, something made up. She had from Sartre, her true love, the idea that you could make yourself up. Her personal story was less liberated than that of any woman I know personally. Her personal story was a disaster. So I didn't have a model or a rationale for this pilgrimage toward a resolution, a resolved answer to the question how should one live one's life as a woman?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 44:23: I mean, it sounds as though there's a kind of romantic sense of direction to life, you know, and a feminine sense of direction to life, and I don't know what else. There are other elements you've talked about. You know, you've become a philosopher, so there are other elements in one's life than these two. But you don't discount that romantic urge and yet you're fully aware of its dangers.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 44:56: Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 45:03: And that's a lot of the drama of a person's life, and especially, perhaps, of a woman's life because of its vulnerabilities and so on.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 45:11: The vulnerabilities are defining. The lie, the deception in de Beauvoir's book, the Second Sex is that by thinking differently you can be less vulnerable. Oh, no, no, no, no, no, no. I remember on 86th and Lexington and I see a girl waiting for the bus to cross town. It's night, she's wearing a really short skirt and maybe fashionable boots, and she's asking me. I cross the street, she's a foreigner, she's English. Is this the way to go to the West Side? I say yes, and then she says is this the right skirt for New York? I said it's a little short, honey, it's a little short for New York night.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 46:27: The vulnerability? No, there's no pretending otherwise, Hell, you can get pregnant, you can get knocked up. What are they talking about? Free sex, it ain't free, it's very expensive and it's different for a woman than a man. And what was a disaster worth considering drowning myself, the loss of virginity, then, now, if you're carrying virginity into your 20s, that's supposed to be a disaster. Listen, you can't win. These are not good frames for a woman trying to figure out within, trying to ask and answer the question within what frames can I and should I live meaningfully so that my life is not a mess, is not something I regret.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 47:48: Is there some general answer to that question, or is it a question for each woman simply to navigate through her own life?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 48:02: Well, one helpful feature, which I don't think we have as yet, would be to clear away some of the misleading pseudo-encouragements. There's no difference between a woman and a man, there’s no reason for modesty, for privacy in the bathroom, in the bedroom where you sleep, in the shower, no difference, just get in there and keep punching a little fella. No, there's a hell of a lot of difference. You can get pregnant. You can get raped. You have a shorter period for having children than a man does. You are still on the receiving end of sexual preference. You can't strong-arm a man into an erotic relationship, above all, not one that is protective of you. If you get left, you're more likely to feel more used than a man might. Women much younger than me tell me that the fate of a woman, of this woman, my story, deployed in Confessions of a Young Philosopher, draws recognition from much younger women. I suspect that if you cleared a lot of myths away, a lot of fashionable misunderstandings away, it would be a darn sight easier to make your way as a woman than it is today.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 50:22: Yeah, and you often report, after conversations with women younger than you, a kind of confirmation that what women across the generations and eons you might say really want is love from the right love, and love with commitment, like marriage and so forth. Not fly-by-night love, but love with commitment and with caring. You know, and as you know, I practically think the woman deserves to be worshipped. You find the right woman and it's the best thing that can happen in your life and you shouldn't let it slip by and slip out of your grasps. A lot of men have a good woman and take her for granted or even wander around, you know, as if they're in a field of daisies or something and you can just go pick flowers. But no, it's more serious than that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 51:27: And if you have the right woman for you, hang on to her, do everything to make her understand and feel daily that you love her, that you love her and, as I say, practically worship her. Well, you don't have to be as gaga as Jerry happens to be, but it is a kind of ultimate value in one's life. They're totally different. Live a loveless life, a life alone or a life with someone you love, what a difference. That's everything. That's everything.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 52:03: Yeah, it is everything. And I come back to the biblical model, these three founders of what will be a covenantal relation with God through time, through chronological history, not history with fireworks, but step by step, by step. Yesterday is earlier than today, tomorrow will be later. That history, chronology, what are you doing with your time? Has God an influence, a factor? How are you making sense of your time? Where are you? Those three patriarchal founders of the covenantal relationship each one, before he can get started or as a condition of his life, has to have the right woman. That seems to me better than Tristan, Iseult or Dante and Beatrice, all of which do not live step by step in chronological time. Hamlet and Ophelia no, Mr Prince of Denmark, marry the girl. Stop being horrible. You know, maybe she can help you. She's not that stupid. Maybe she can figure something out about who killed the king, and so forth. I think a lot of people feel this and think this, and it's unsayable, it's taboo, it's considered foolish, romantic and foolish. It's intelligent, there's emotional intelligence here, and if it's peculiar to one culture or some rare moments in a culture, it doesn't have to be. You know, there are lots of things that we have from one culture that we don't feel shy about saying hey, I can use a bit of that coffee. We have it from Vienna, which got it from its mortal enemies, the feared opponents. Hey, it's great, I wouldn't be without it. Coffee, so true love, it's as good as coffee. I recommend it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 55:00: Well, you often tell me, I don't drink coffee. I don't like the taste or the smell, so I'm unusual. But you often tell me coffee is the meaning of life. So there, that's one element, in fact, to be enjoyed, to be prized, you know to be given its place in one's life.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 55:19: Ah, it's a beautiful thing.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 55:22: Maybe on the wonderful meaning of coffee is a good place to conclude, and we all agree to that proposition.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 55:33: In varying degrees.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 55:34: So thank you very much, sweetheart.

Scott Langdon 55:59: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.