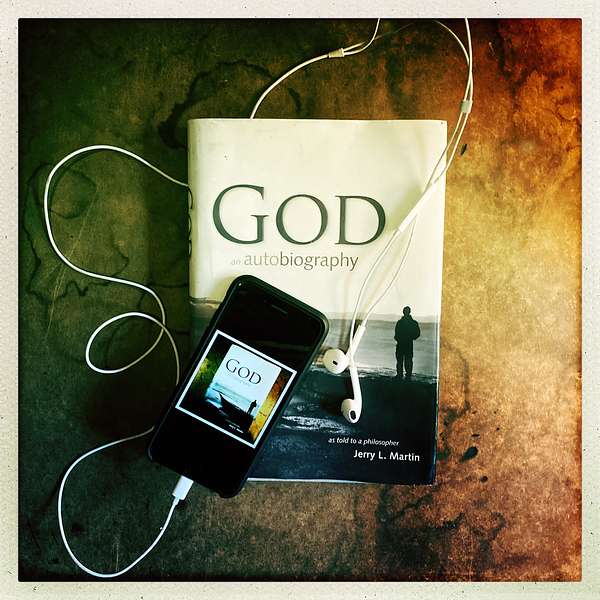

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

252. From God to Jerry to You- Hearing God Speak: An Agnostic Philosopher’s Awakening

What happens when a lifelong agnostic philosopher prays for the first time—and God answers? In this episode, Jerry L. Martin reflects on the experience that transformed his life and inspired God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher. Through love, gratitude, and trust, Jerry moves from intellectual doubt to an intimate conversation with the Divine.

He shares how falling deeply in love opened him to the reality of spiritual experience, leading to his first authentic prayer and an unexpected vision beside the Potomac: a shimmering fountain and a voice saying, “I am God … the God of all.” From that moment, Jerry’s understanding of knowledge, faith, and revelation changed forever.

Join host Scott Langdon as he explores themes of spiritual discernment, intuition, and calling—how we learn to trust what speaks through love, insight, and inner peace. Whether you call it God, Source, or higher consciousness, this episode invites you to listen more deeply to the voice within and discover meaning in the experiences that call your name.

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

The Life Wisdom Project – Spiritual insights on living a wiser, more meaningful life.

From God to Jerry to You – Divine messages and breakthroughs for seekers.

Two Philosophers Wrestle With God – A dialogue on God, truth, and reason.

Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue – Love, faith, and divine presence in partnership.

What’s Your Spiritual Story – Real stories of people changed by encounters with God.

What’s On Our Mind – Reflections from Jerry and Scott on recent episodes.

What’s On Your Mind – Listener questions, divine answers, and open dialogue.

Stay Connected

- Read the book: God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher at godanautobiography.com or Amazon

- Share your questions and reflections: questions@godanautobiography.com

- Subscribe and listen free wherever you get podcasts

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon [00:00:16]: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast — a dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered — in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him.

Scott Langdon [00:01:00]: Episode two fifty-two. Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, I’m Scott Langdon, your host. And this episode marks the latest in our very popular series, From God to Jerry to You. What would cause a lifelong agnostic to suddenly have the desire to pray? For Jerry, that answer was pretty simple. At least he knew the answer in his particular case. It was love. His deep love for Abigail caused him to be full of gratitude. And it was that gratitude that led to a desire to pray—to offer thanks to, well, to whomever. Love, gratitude, prayer, awakening to God’s presence. Can I be of service somehow? Here’s Jerry Martin. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:02:16]: You know, I’ve often asked myself, since my remarkable experience of hearing God’s voice speak to me, and of then finding that God was willing to answer my questions—leading to an entire book filled with (85–90% of it is) God speaking to Jerry. And what I wondered about is: why me? Why on earth me? It seems I don’t have any of the qualifications, you might say, any of the characteristics that God would look for in somebody to give this kind of extended revelation to.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:03:29]: I wasn’t religious, I was philosopher and that counts for something I suppose, we study the great wisdom traditions mainly of the Western side, but beyond that as well, but I did not have an interest in religion, I didn’t have a belief in God, I didn’t even have a question about God. In other words, I wasn’t pondering whether to believe in God. I know I’ve had friends who couldn’t believe, but very much wanted to, and yet God seemed incredible to them, or something of that sort. But no—philosophy gave me plenty of wisdom, and I was happily going along with that. And so I didn’t know much about religion. I knew what just anybody who goes to college—you pick up a lot if you do a liberal arts major—and that was about the level of understanding I had. So why me? And then I look at other personal qualities. You watch the movies about religious figures, and they’re always kind of larger than life and have, you know, hair that’s electrified and so forth. They have great personal charisma that we feel even today across the many centuries—maybe since some early figure appeared—yet they are still compelling figures to us and to those who follow in their tradition. So anyway, it just seemed that if this were a job opening, I would not be well qualified for it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:05:10]: And so I look back at the first episodes of God: An Autobiography to see, well, what was going on? What did I bring to the situation, you might say? Stop thinking about it in terms of a personal résumé—as if I were applying for a job—but what was going on that prepared me for the assignment I ended up being given: to tell God’s story? Well, the first thing that happened, I think relevant to this question, is that I fell in love. And I hadn’t really believed in romantic love, but I fell totally head over heels in love. And I thought, what is this? So I went and read the relationship books, and I found that what they tell you is: don’t trust it. It’s all projection; it’ll fade in about six months. You think this person is perfect—that’s you projecting some image on them—and that image isn’t true. By six months the bubble will burst, and then you’ll move on. Maybe by then you’ve discovered you’re compatible, and so you stay together for that reason. Anyway, they’re all skeptics, and I kept reading these, wondering: haven’t any of these people ever been in love? At least not in love the way I was in love.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:07:00]: And when I look at that phenomenon—what I was going through—retrospectively and reflect on it, what strikes me is that I held steadfast. I trusted the love. The love was a phenomenon that appeared to me in experience. It manifested itself; it was right there, overwhelming me. And I believed in the phenomenon. Rather than discounting it—they all teach you to discount it, put it in big brackets, put an asterisk that “this fades away”—I didn’t do that. I said, let’s go with this. And I never had any doubt from day one that what I was going to do was marry Abigail. Now, I’m a cautious person, and I made a point—as a matter of policy—to wait six months before popping the question. But that was a mere arbitrary device, just because I knew people can be wrong. I’m not a fool, I know one can get carried away, but I didn’t believe that is what happened here. When I paid close attention to this experience, to the phenomenon of love, it commanded respect and it earned trust. And so, anyway, I trusted it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:10:14]: I trusted it so much that I felt the gratitude of being in love—a love having come into my life, not earned by me. Abigail phoned me one day out of the blue, and it went from there as we got to know each other long distance. I fell in love on the phone before I ever met her. And so from that day that I fell in love with her on the phone, I was never interested in any other woman. There was no other course to my life except pursuing this love. And so I felt so grateful for this having come into my life that I—well, I suppose you’d call this a kind of trust also—I had a feeling of expressing gratitude. Now, I didn’t believe in any object of the gratitude—whom I would be expressing this gratitude to—maybe just to a benign universe, a lucky day, thanking my lucky stars. Whatever it was, I felt so profoundly moved that I literally fell to my knees and said an earnest prayer of thanks to whomever, or whatever, had brought this love into my life. That happened a time or two more.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:11:18]: At some point—she was in New York with a full-time job; I was in Washington, D.C. with a full-time job—we didn’t want a commuting marriage. What were we going to do? And so I prayed about it. We were sitting—it was the summer, August, late on a Saturday—on a park bench facing the south side of the Potomac, where you see the Lincoln Memorial across the river. And I just prayed for guidance. My beliefs had not changed. I still didn’t believe in God or anything else, but it just seemed natural to pray. And I did—without forethought, without expecting anything—just a spontaneous thing in my mind. I didn’t say it out loud, but I prayed for guidance. And first thing, as I recount in God: An Autobiography, a kind of vision appeared. What in the old days they would call a vision—it was kind of like a hologram, a few feet in front of me: rising, sparkling, multicolored fountain. I took that to be a kind of answer to my question—something very reassuring. And then a voice spoke, and I knew it wasn’t me speaking, and so I asked, “Who is this?”

“I am God.”

I knew enough about religion to know there are a lot of them, and therefore, in a sense, a lot of gods. So I said—going back to my Judeo-Christian tradition—“The God of Israel?”

“I am the God of all.”

From that day on, I had a relationship with God.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:15:09]: I never doubted. It was strange. I’m an epistemologist. What we’re trained to do is to doubt. The basic question of epistemology is: do you know what you think you know? We, as human beings, do we know what we think we know? And if so, how? There are all kinds of reasons for posing skeptical questions about every category of human knowledge. And in spite of that, here again I was presented with a phenomenon in experience—God speaking to Jerry—and the voice was too real (as real as talking to Abigail on the telephone), and benign, and somehow authoritative for real doubt. I just could not actually really doubt. I knew how to go through the exercise of doubt, much as I’d gone through the exercise of waiting six months before proposing to Abigail. But I did due diligence. I couldn’t actually doubt, but I know that I’m fallible, everybody’s fallible. There are no infallible moments. So I went and read the literature. In fact, I called a friend who I thought would know more about this, and he said, “Oh, that’s the question of spiritual discernment.” And there’s literature on how you know it’s the real thing when you have an experience of the sort I had—some kind of voice, vision, or other epiphany coming to you. How do you know it’s the real thing? The religious (often Christian) literature even asks: how do you know it’s not the devil pretending to be God? They say Satan is a very good imitator, a very good mimic, actor, con man. So you go through a lot as you check out the instrument. The instrument of receipt of revelation is the human being—the human person. And so you kind of check yourself out. A big danger signal is pride: if you think, “Hey, God is talking to me, therefore I’m the boss of the universe. I get to tell everybody else what to do and believe.” If you get carried away—yeah—probably not God. That seems a lot like Satan or just your own inflated ego welling up. I did have one moment like that. I thought, “Wow, this is really special.” And as soon as I felt a kind of welling up of pride—of feeling special—the line went dead. Before, I’d felt the presence of God more or less all the time. And here it was literally as if someone had cut the wires while I was on the phone and the line just went dead. So I said, “Ah—don’t do that.” I look at the pattern here: it’s a pattern of encountering something real in experience—something real presenting itself in experience: the love presenting itself, the divine voice presenting itself—and then trusting that. You probe it; you question it. Trust should never be blind trust, but you don’t have to give up the trust.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:19:45]: As we thought more about these questions in life—Abigail and I were discussing the other day—how does a person know what their calling in life should be? What should I be doing today, this year, in the course of my life? What should my priorities be? Abigail often says of a task, “It has my name on it.” Well, how do you know it has your name on it? A lot of life is lived by something like intuition—gut feelings, intimations. Something’s here; something’s presenting itself. A road is opening; a door is opening that I should go through. A friend says something; you think, “Oh, this is telling me something.” There too, you have to start with trust. You trust your intuitions; you trust what presents itself in your experience. You ponder whether what a friend says is a tip-off to meaning in your life—is it a way that God has of coming to talk to you? And you take any experience—it can be feeling a certain way as you look at the trees in the spring—and that feeling is somehow telling you something about the nature of reality and maybe its ultimate meaning. I had a friend on a trip up the Amazon—a great lover of nature—and the little boat they’re chugging upriver on was one with a sleeping cabin in the center. She got restless in the middle of the night, went up to the little deck, and looked up. The sky was so full of stars—in a way that in urbanized environments you never see because it’s not dark enough. There’s nothing going on except you and the jungle around you—not even sounds except the little murmurs animals make—and the sky empty except for the vast Milky Way in which you are immersed: thousands, millions of stars. I told her: go write that down, because it will fade over time. You can think, “Well, this was quite a moment seeing that beautiful sky,” but it could be the universe disclosing something about its profoundest nature to you. It could be a rare moment of the presentation of ultimate reality, or the profoundest aspects of reality, being shown to you. So take your experiences in; probe them; see what they have to teach you. And if they seem right upon reflection—and test, as I was saying: your human self (including your body) is the instrument of revelation or divine communication—see how it feels upon reflection. It should perhaps feel like harmony, a kind of peace of mind: everything in right order, not out of order. And if you’re reaching, that’s a bad sign. But if you have this subtle feeling of something profound presenting itself in your experience—it could be love; it could be a divine voice; it could be an ethical intuition (“this is wonderful,” or the opposite: “this is something I should be protesting”)—you don’t act out of ego. You take it in, probe it, let it settle with what I call a clarified soul, and then trust it. If you trust an experience—an intuition—you might just learn something. But if you doubt them all, you’ll never learn anything. Well, keep that in mind.

Scott Langdon [00:20:08]: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with Episode 1 of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted — God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher — available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God’s perspective — as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I’ll see you next time.