Climate Confident

Climate Confident is the podcast for business leaders, policy-makers, and climate tech professionals who want real, practical strategies for slashing emissions, fast.

Every Wednesday at 7am CET, I sit down with the people doing the work, executives, engineers, scientists, innovators, to unpack how they’re driving measurable climate action across industries, from energy and transport to supply chains, agriculture, and beyond.

This isn’t about vague pledges or greenwashing. It’s about what’s working, and what isn’t, so you can make smarter decisions, faster.

We cover:

- Scalable solutions in energy, mobility, food, and finance

- The politics and policies shaping the energy transition

- Tools and tech transforming climate accountability and risk

- Hard truths, bold ideas, and real-world success stories

👉 Climate Confident+ subscribers get full access to the complete archive, 230+ episodes of deep, data-driven insights.

🎧 Not ready to subscribe? No worries, you’ll still get the most recent 30 days of episodes for free.

Want to shape the conversation? I’d love to hear from you. Drop me a line anytime at Tom@tomraftery.com - whether it’s feedback, a guest suggestion, or just a hello.

Ready to stop doomscrolling and start climate-doing? Hit follow and let’s get to work.

Climate Confident

From Leftovers to Energy: Synthica's Circular Solution

This episode is only available to subscribers.

Climate Confident +

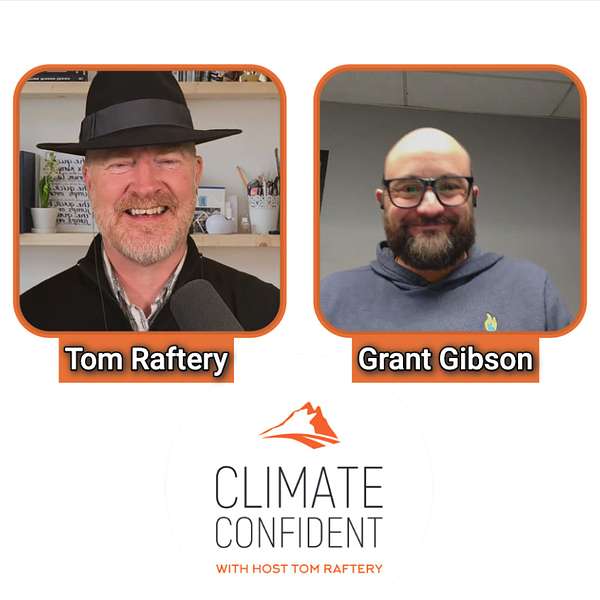

Get access to the entire podcast's amazing episodesIn this insightful episode of the Climate Confident Podcast, I had the pleasure of chatting with Grant Gibson, Chief Development Officer at Synthica Energy. Synthica is at the forefront of transforming industrial by-products, specifically from the food and beverage sector, into renewable natural gas through anaerobic digestion. Grant shared the intriguing journey of Synthica, from its early days founded on a shared passion for the environment and sustainable solutions, to its current status as a key player in the renewable energy market.

We delved into the nitty-gritty of anaerobic digestion, exploring how Synthica's approach not only provides a sustainable alternative to conventional natural gas but also significantly reduces carbon emissions. Grant highlighted the challenges and complexities of setting up such facilities, including zoning, utility negotiations, and the intricacies of managing waste streams.

One of the standout aspects of our conversation was the emphasis on the circular economy. Grant elaborated on how Synthica creates a closed loop of energy production, transforming waste into valuable resources, thus contributing to a more sustainable and environmentally friendly energy landscape.

Furthermore, we touched on the importance of community engagement and education. Synthica is not just about converting waste to energy; it's also about inspiring the next generation and showing them the possibilities within the green energy sector.

Don't miss this episode if you're interested in the intersections of sustainability, technology, and business. Grant's insights provide a fascinating look at the potential of anaerobic digestion to change how we think about waste and energy.

For more details about Synthica and their pioneering work, visit their website at www.synthica.com. Join us in exploring innovative solutions that are not just good for business but are also vital for our planet's future.

Podcast subscribers

I'd like to sincerely thank this podcast's amazing subscribers:

- Anita Krajnc

- Cecilia Skarupa

- Ben Gross

- Jerry Sweeney

- Andreas Werner

- Stephen Carroll

- Roger Arnold

And remember you too can Subscribe to the Podcast - it is really easy and hugely important as it will enable me to continue to create more excellent Climate Confident episodes like this one, as well as give you access to the entire back catalog of Climate Confident episodes.

Contact

If you have any comments/suggestions or questions for the podcast - get in touch via direct message on Twitter/LinkedIn.

If you liked this show, please don't forget to rate and/or review it. It makes a big difference to help new people discover the show.

Credits

Music credits - Intro by Joseph McDade, and Outro music for this podcast was composed, played, and produced by my daughter Luna Juniper

Renewable natural gas is very similar to natural gas. When you put it, one unit of renewable natural gas side by side with conventional natural gas burns the same, has the same heat value. The big difference with, with renewable natural gas is that you don't have the carbon emissions that you do with conventional natural gas, so,

Tom Raftery:Good morning, good afternoon, or good evening, wherever you are in the world. This is the Climate Confident podcast, the number one podcast showcasing best practices in climate emission reductions and removals. And I'm your host, Tom Raftery. Don't forget to click follow on this podcast in your podcast app of choice to be sure you don't miss any episodes. Hi everyone. And welcome to episode 164 of the climate confidence podcast. My name is Tom Raftery, and I'm excited to be here with you today, sharing the latest insights and trends in climate emissions reductions. Today, I'm talking to Grant Gibson the chief development officer with Synthica Energy. And in upcoming episodes, I'll be talking to Johan Pretorious and Paul Rowatt from Carbon is Money, fascinating episode coming up next week, week after that Daniel Lawse from the Verdis group and the week after that Julia Saland from EcoVadis, but back to today's episode. And as I said, my special guest on the show today is Grant Gibson from Synthica Energy. Grant, welcome to the podcast. Would you like to introduce yourself?

Grant Gibson:Yeah, thanks, Tom, for having me. I'm Grant Gibson Chief Development Officer with Synthica Energy.

Tom Raftery:Fantastic. And who or what are Synthica Energy, Grant?

Grant Gibson:Yeah, so Synthicate Energy is a developer of anaerobic digestion facilities focused in various markets across the U. S. We use different types of what I call industrial byproducts off of food and manufacturing. Food and beverage manufacturing to where we use the byproducts from those processes and then run them through the anaerobic digestion process. And on the backside of our plant, we end up producing renewable natural gas. Renewable natural gas is very similar to natural gas. When you put it, one unit of renewable natural gas side by side with conventional natural gas burns the same, has the same heat value. The big difference with, with renewable natural gas is that you don't have the carbon emissions that you do with conventional natural gas, so,

Tom Raftery:Yeah. I mean, chemically, it's the same thing.

Grant Gibson:exactly. Yes, it is.

Tom Raftery:Great. Yeah. It's just how you, how you create it. Yeah. Cool. So walk me through a little bit, Grant, through the origin story of Synthica Energy, because as far as I understand, you're also a co founder, right?

Grant Gibson:Yes, I am. I'm a co founder. So my business partner, Sam and I started it back in 2017. Sam and I've known each other for 20 plus years. We've been friends, share love for the outdoors, rock climbing, backpacking, you name it. We reconnected as friends, as many people know, when you have kids and sometimes you part ways with friends and then you come back to the middle of the road and you reconnect and you find out what they've been doing and then they find out what you've been doing and vice versa and, and etc. So, we reconnected as friends back in late 2016, early 2017 and, and we really got together and said, hey, look, you've worked in businesses with me and I've worked in your businesses as well and we, we really just agreed that we wanted to build something cool. And I literally jokingly said, oh, we should build a digester. And he said, well, what's that? And I'm like, well, and I explained it and I said, no, it's a terrible idea. Literally, that's what I said to him because it's a tremendous amount of work, complex, et cetera. and we actually started down the path of reaching back out to customers that I had from a past career in commercial composting. And from there we started to continue to work more and more on it. He already had a the brand Synthica sitting around because he wanted to do something in, in really synthetic fuels. So the name Synthica was around and we got to a point where we both said, all right, we kind of need a brand name for this. And he's like, well, I got this website parked. It's called Synthica. What do you think about that? I'm like, yeah, that sounds fine. Let's use it. And so then fast forward we, again, more and more work was put into it. We raised some seed money to get the the permit to install from the state of Ohio EPA for a Cincinnati facility. And then we went through and formed a JV with a natural gas utility out of Pennsylvania called UGI that helped get the Cincinnati facility up and off the ground. At that point in time, we said, wow, could we really, could we do this across other markets, meaning Atlanta, Houston, San Antonio other markets across the U. S. And and the answer was yes. We ended up finding out there was a big need for the, the type of service that anaerobic digestion provides. And so we started working in other markets and going after permits and and yeah, that's a little bit of the story. And through today, we recently became we did a big equity investment with Goldman Sachs last August which really has allowed us to grow the company, not only people wise, but also fund the projects that we have on deck to be built this year and into next year.

Tom Raftery:Fantastic. Congratulations.

Grant Gibson:Thank

Tom Raftery:why why anaerobic digestion? I mean, that's not one that, you know, instantly comes to mind. What was it that interested you in anaerobic digestion?

Grant Gibson:Yeah, so during my career as a commercial composter I met folks at Procter Gamble and during that time when we got to talking about the feedstocks or the waste streams that I was composting, and when I talk about composting, I was doing it at a commercial scale, we were taking in on our peak, 250, 300 tons a day of all different types of food byproducts, paper sludge, yard waste, and so, they came to me and they said, Hey, you've got these feedstocks that are coming in the door that you're managing and composting. We've got a business center up the road. We'd love to build a digester on your compost site. And then use the same feedstocks to power the digester, feed the digester, and then we'll pipe the gas up to our business center pipe the renewable natural gas up to our business center, and so that's really where the idea was born. It didn't come to fruition obviously but that idea stuck with me and then that's when Sam and I reconnected and the idea was kind of lingering in the back of my mind of what is something that that is pretty darn cool at the end of the day that we could build together. When he and I started on that journey, we really, it, it was truly just a pipe dream. I mean, we didn't really think it was going to take off to where it is today.

Tom Raftery:And, when you initially said to him it was a terrible idea, why did you say that?

Grant Gibson:I, I joke and I say we're, we figure out some of the most complicated puzzles that could ever be put in front of someone. Because with an anaerobic digester, you have to figure out and, and we learned a lot from touring other digester sites in the U. S. And so when you take the complexity of learning what's worked and what didn't work for other digesters across the U. S., and not to mention that there's not a large number of anaerobic digesters across the U. S. So, in comparison to, say, for example, in Europe, where when you look at the complexities associated with anaerobic digesters, we set out, and when I say we, Sam and I set out to, to locate these digesters in heavy industrial areas, and so when you couple that with finding the right zoning, finding an area where you can, a, a, a property that you can inject the renewable natural gas, and then also have access to industrial sewer. So we do produce a wastewater on the backside. So, so zoning an interconnector where you can inject the gas industrial sewer, and then concentration of, of nearby food and beverage manufacturing. And then not to mention also just the ability to the access of basically truck traffic getting in and out of your location. You take all of those and you say, all right, how many properties do you have at your fingertips or what's available? It becomes a very, very, very small number. And so, figuring out all those parts and pieces, then not to mention the fact that most utilities that you approach and say, Hey, I'm going to build an anaerobic digester in your footprint. And oh, by the way, I want to inject this thing called renewable natural gas into your natural gas pipelines. And they say, hold on, time out. This is a first of its kind project in our footprint. We're going to have to think about that or go ask 50 different advisors and consultants and you name it in order to say that, okay, as a utility, we're comfortable with it. A lot has changed in the last, call it five to seven years as far as utilities being comfortable with it. But again, there are so many complexities associated with locating in a heavy industrial area to where it's convenient for food and beverage manufacturers to where they're not driving their byproducts or their waste long distances. So, yeah, that's where I joke and say it was a terrible idea. We, I said it's a terrible idea because just the number of complexities associated with that type of facility.

Tom Raftery:okay. And walk me through then what it is you guys are doing. You're taking waste products from industry, digesting it anaerobically, creating gas, plus, as you mentioned, water, plus there's obviously some solid matter left over at the end. Who are the customers for those, I don't know, one, two, three products? And who is it you're typically buying the stock from, feedstock?

Grant Gibson:Yeah, so I'll start with that, that last piece first. In the U. S. it's a little different. We actually get paid to take, we actually have a tipping fee for the waste streams. So, a little different there where let's say if you're a beverage producer, let's say a brewery, and you have a spent yeast waste stream that comes off of your brewery. Not necessarily the spent grains because spent grains are typically going out for animal feed. Or it's the spent yeast, so it's like the yeast, the hops, water, other byproducts of the brewing process. The brewer is actually able to send that to us in a tanker truck where They offload it straight into the process. We get paid a tipping fee per gallon. Now, if we look at the back, what I call the backside of the plant, to your point, Tom, around So, when there, when the, the, the waste, I'll call it a heavy waste water comes out of the plant. And when I say heavy, meaning it's mixed with, to your point, solids we call it a digestate. So, it's a solids and a liquid mix, so it's a slurry almost where it comes out. We've harvested all the energy off of it anaerobically to where we're left with this super high nutrient digestate. We actually take it from there and, and centrifuge out the solids. And that's again what I mentioned earlier about learning a lot of lessons along the way with all the different digesters. We centrifuge out the solids, so we spin it out, think of it like your washing machine where it's spinning, sending all the liquid out, keeping your clothes inside. We actually take the solids from the centrifuge. And then send that out to beneficial reuse. Everybody from composters to soil manufacturers, that kind of thing. So it's a a much smaller volume. More dense, more of a solid kind of, we call it a cake. To where we're able to send that out for beneficial reuse. Then the liquid fraction, what we call the effluent. We have on site pre treatment, so we take it from a, call it a higher strength, and we knock it down to what I'll call household sewage strength, and then from there we discharge straight to sewer. Sewer districts don't like super high organic loaded waste streams, liquid waste streams. So through our process, we're knocking down that high strength organics all the way down to very, very, very small numbers. And then also we knock it down from a higher strength in a different sense to where it's more that household sewage to where the local sewer districts absolutely love that type of material, that waste coming down the drain. So that's how we, we offload that, that solid fraction of the digestate, the liquid fraction, and then the gas piece of it, we generate two different, call it products there. One is the actual physical gas, the molecules. So, we send it out to whether it's a marketer, whether it's a marketer of natural gas it's traded just like traditional, what's in the pipe today, natural gas, a marketer, a utility can buy it, whoever. Then we also have a piece, what we call some folks refer to it as a renewable thermal credit. Some other folks call it like renewable energy credit. It really is all the same thing to where if you're a, and we focus on customers for the environmental attribute piece of it, we focus on customers that say, Hey, I know that I'm not required by regulation to buy these environmental attributes to reduce my emissions, but I'm going to go ahead and do it anyway, so it's what's called the voluntary market. And so we sell into the voluntary market. So it could be utilities that don't necessarily have a federal or any kind of regulatory requirement to buy environmental attributes. It could be a utility, it could be a private corporation, a large corporation that wants to lower their emissions based on buying those environmental attributes. It's a whole wide range of different customers. We don't focus on what's considered a low carbon fuel market out on the west coast of the U. S. We do focus heavily on the voluntary market. So, that's kind of, like, again, where the solid liquid fraction goes, and then physical molecules of the gas, and then also the environmental attributes.

Tom Raftery:Okay. And the, the solids that you're giving out for beneficial use, is that you're giving it away or you're selling it or it's, or which?

Grant Gibson:Yeah, I would love to say that we're selling it. It's one of those things where we try to do low cost, no cost but we do have a cost associated with offloading it because there's transportation associated with hauling it from our digester location to a compost or a mulch manufacturer you name it.

Tom Raftery:Okay. Fair enough. Fair enough. I was speaking recently to a pharma, a pharmaceutical company. And we were talking about their emissions and one of their big sources of emissions is obviously industrial heat. So I can imagine for industrial customers, I mean, lots of different industries use fossil fuels for that, for industrial heat, not just pharma. Is that a, a market you're chasing? Is, or is that, is that market chasing you?

Grant Gibson:That's a great question. So I would say, yes, it's a little bit of chasing us because that pharmaceutical company, that, that's a great example of the voluntary market. They say, hey, our, our biggest emission is, is heating, right? And so, within the anaerobic digestion market in the U. S. and, well, more so around renewable natural gas market there is a tremendous amount of demand, but the amount of supply is just nowhere near coming close to meeting the demand. So, supply being small, demand being really big. I would say that when I look at the, and if you notice, I didn't really mention it being part of the complexity of that big puzzle that I talked about earlier where offloading, having an offtake for the environmental attributes piece of it and the, and the physical molecules. That's the easy part because there's so much demand for it. It's Oh, here's a term sheet. Here's a term sheet. Here's a term sheet from all these different providers. And it's just a matter of Okay, who do we want as a customer? On the offtake side who are they, are they going to be around in 10, 15, 20 years, that kind of thing. So, yeah, demand is really high for, yeah, absolutely chasing us.

Tom Raftery:Nice, nice. Does that mean you can charge a premium for renewable natural gas versus regular fossil fuel gas?

Grant Gibson:Absolutely, yeah, it, when it comes to the environmental attributes piece, you can. The physical molecule gas just gets traded at a, called a commodity rate, and sold at a commodity rate to where, but the environmental attributes is really where that big premium comes in. If you look at, call it, it's probably, if you said in the U. S., the commodity rate right now for natural gas is, traded at, I'm going to round up and say $3 for the environmental attribute piece of that, you're probably looking at a a 7 to 8X on that, so you're at 21 to 24. per unit, per environmental attribute associated with the, with the RNG. So, yeah, it's definitely a premium. Do I ever see it leveling out and going down? Maybe. It's possible. It just depends on what the industry does over the next 10 years.

Tom Raftery:hmm. All right. And Sourcing your sites, how, how do you go about deciding where to build your digester? Is it, do you, do you build them in your customer's backyard or, you know, or do you build it where it's most convenient for you and then get the gas from there to your customer by tanker truck, by, you know, whatever else means by piping, whatever?

Grant Gibson:Yeah, so we try to, we try to locate in an, a region where there's a high concentration of food and beverage manufacturing. We've looked at what we call co locating. Like, in a, on the same property of a, of a large food or beverage manufacturer. That tends to get pretty sticky just because of risk, liability, you name it, on both sides, both our side and their side, so, it's interesting because I, I never thought in a million years that I would be using what I went to school for, which is geographic information systems. I went to school for that at a high university in Ohio, and I never thought that I'd be using that one day to cite digester locations. So, a lot of mapping, a lot of geospatial analysis, you name it. And so, that helps us really whittle things down, the options down pretty fast, so I can overlay. And we've got team members that do that today where they will overlay dots on a map that show concentrations of food and beverage manufacturing, they'll overlay the zoning, they'll overlay pipelines, they'll overlay all these different layers, and it, again, as I mentioned, it'll really whittle down the options that we have when it comes to property. So, yeah, I mean, we, we try to do it pretty quick to where we can give it a quick pass or fail and then we can move on to the next property kind of thing. If we find a property and we say, ooh, that looks good, it meets all the criteria before we even put boots on the ground. So, yeah, it's again, I never thought I would be using it, what I went to school for, how many ever years later 21 years later that I'd be using it to, to site anaerobic digesters across the U. S.

Tom Raftery:Okay. And is there anything particularly unique about your anaerobic digesters versus anyone else who's doing anaerobic digestion.

Grant Gibson:So, we do not, we don't use anything proprietary. We don't have any proprietary technology. We use commercial off the shelf equipment, whether it's blowers, tanks, mixers, receiving equipment, you name it. It's all very very, very standard stuff. Where the big differentiator for us is one is the convenience of where we're located. If you look at If you compare us to other developers of digestion facilities. Typically has been further out in more farm or rural settings. We don't, we do not digest, we do not take in manure from whether it's cattle or, or swine. So that's a big differentiator right there. The second to that is the fact that we have the ability to offer up our offering to a customer that says, Hey, I want to give you 20, 000 tons of this particular waste stream and yeah, I'm going to pay you for it to get rid of it. What do I get in return? We have different offerings that we're able to provide to that customer to where it's more than just an outlet. Because we know and we've learned over the last couple of years that we have to be more than just an outlet for them, for that manufacturer to say, Oh, I send it to a digester. Yeah, it's great. Everything's merry. But for them, really, what's a true compelling reason for them to go through, I don't want to say the headache, but just the, the exercise and the commitment to say, okay, we're going to send it to Synthica versus sending it to, whether it's land application or sending it down the drain or even landfill, right? Because truly, yeah, economics are a big driver. Are we cheaper than the landfill? Sometimes yes, sometimes no. Are we cheaper than the sewer department or the sewer district for sending a waste, a liquid waste down the drain? Sometimes we are, sometimes we aren't. It really just becomes a, an exercise of, okay, where are they sending it today? How much are they paying today? Meaning the manufacturer. And then from there it's, okay, if you send us 20, 000 tons of waste, we have these other offerings that we can provide kind of call it call it conversion as a service. Where we're acting as infrastructure or even infrastructure as a service to where we have different things that, different products that we can offer in return outside of the, what I mentioned earlier, so.

Tom Raftery:Okay. And are you thinking at all of maybe licensing the technology for other people to use, so you build a digester and license someone to use it or sell them the, the blueprints so that they can create their own based on your model and charge them a fee or just as a way to scale.

Grant Gibson:No, we really haven't thought about that. I guess the, the primary reason for that is because we because if you look at the markets that we're in, that we're building in, San Antonio, Texas, Houston, Texas, Atlanta, Georgia basically, we're going to be south of Louisville, Kentucky. We're going to be right outside of New Orleans, Louisiana. If you look at all those markets, there's no infrastructure at all. And so, we are experiencing some, call it, we are experiencing first mover advantage in, in purely the organic space, and when I say the organics, meaning we don't take in manure, we don't take in treated sewage from municipal wastewater treatment, we're focusing 100 percent on food and beverage or industrial byproducts. So I haven't really thought that way just because there's no real infrastructure right now as it stands. So we're saying, hey, look, let's just, let's do it ourselves. Let's go out. Now are we building them on our own? No, we're, we're bringing in contracting firms to do all of that. Because in order to scale, we don't need a construction arm. There are plenty of design build firms out there that can help scale, help us scale pretty quickly.

Tom Raftery:Okay. And why not manure and why food and beverage?

Grant Gibson:Yeah, so. A couple things. One is, as I mentioned earlier around the location. Typically on farm digestion, those digestion facilities are either paying for the manure or they're taking it at no cost. And so when you look at their top lines of revenue, we have two, call it three, where we have tipping fees, physical molecule gas, and then environmental attributes. And then we don't rely heavily on the the low carbon fuel markets in the West Coast. So, we, over the last, the first few years that Sam and I were putting Synthetica together is that We said, look, the low carbon fuel market is pretty risky. The market, the credits that are available through that market are can shift with political winds. And so, at this, I joke and say, at the stroke of a pen, those credits that are associated with a low carbon fuel market can change overnight, and if you're relying heavily on one revenue stream just from that low carbon fuel market, your business can take a can have that that can have a major impact on the digestion facility from a livelihood perspective. So We've strayed away from manure. It is what I call relatively saturated. All the big dairies and all the big, most of the large swine farms are, are spoken for. They've been producing renewable natural gas for a number of years now. Now developers are out scrambling around trying to connect dots between a bunch of small ones to make a larger one. Call it larger production of RNG. So, we really haven't gone after that because we want to be. We want to build, we, we both agreed, Sam and I both agreed that we wanted to build the infrastructure in, call it the urban areas, where it's really, really needed versus having to haul waste further and further out to those on farm digestion facilities, so.

Tom Raftery:Okay. That makes sense, I guess. Yep. Yeah. And looking forward, are there any particular innovations in anaerobic digestion technology or processes? That you see as kind of game changers for the system.

Grant Gibson:Yeah, so capturing all the tail gases associated with when you, in the last step of anaerobic digestion, you produce raw biomethane, and then from there you have to upgrade it. So you're stripping out moisture, CO2, hydrogen sulfide, reducing oxygen content, you name it. And so, those are all considered tail gases, and so being able to capture all of the CO2 at a, at a rate that makes sense, meaning from an equipment CapEx versus return. So that's one that we're doing right now that, that should add a lot hopefully. And then and then even as you start to build larger facilities potentially, that rather than sending out your cake for beneficial reuse, are there ways that you can run That cake through pyrolysis or different types of thermal treatments to where you can basically create a syngas and then send that syngas back into the It, you can run that syngas into the upgrader and then help produce even more RNG. So, yeah, there's a couple different avenues that we're working on right now that can really I don't know if I'd call it game changers, but it definitely helps us a lot because we do want to capture everything that we produce and make sure that we're not creating additional burden. We're actually decreasing burden on the earth on the, in the, from environmental perspective. So, yeah, I would say that those are the two big ones for us. I don't see anything. Like monumental in the next couple of years changing for us, but I mean that could all change with the way technology is advancing.

Tom Raftery:Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. And what are you doing with the tail gases?

Grant Gibson:Yeah, so we're working right now actively to capture all those tail gases. Because with our first facility in Cincinnati, it'll come online here later this year, and we hope to have that ready to go by the time it's by the time it comes online. So capturing those tail gasses, specifically the CO2, so it's not a large volume, but it's a, it's a volume large enough to where it makes sense to spend the time, the effort, and the money on installing equipment and partnering with a company that does that.

Tom Raftery:for what end?

Grant Gibson:Yeah, so you can capture the CO2 and you can actually create. You can actually, because our tail gas, our CO2 tail gas is like 98. 9 or almost 99 percent pure so you can actually produce food grade CO2 from that. So for carbonating, you name it.

Tom Raftery:right, right. Okay. And what about any policy changes or incentives? I mean, the IRA was just, as an Irish person, I shouldn't be saying IRA loosely, but the, the infrastructure act in the U S or the

Grant Gibson:Yeah, yeah.

Tom Raftery:act are there any policy changes? Has that helped, for example, or are there other policy changes that could or should be made that would help?

Grant Gibson:there are more, there seems to be more and more states adopting a renewable fuel standard. I know New Mexico just adopted one. I think Michigan is pretty close. I think a few states on the East Coast are close. I think the more states that adopt a renewable fuel standard will encourage more and more RNG production. But again, it lends itself back to the credit market where you have renewable fuel standards out west that are part of that, that are that low carbon fuel market to where again, you want to make sure that you foster growth and adopt an alternative fuels. But at the same way, same time, you have to make sure that you don't have. Catastrophic market events whether it's a shift in policy once the RFS is set up, and then if you have a major shift in policy that that can again create a catastrophic event, but I think the more and more that states adopt renewable fuel standards I think that'll help a lot I mean, yeah, and then we'll see what, I know that more and more large truck, large truck engine manufacturers are coming out with them. Engines more geared towards compressed natural gas and I mean you can do the same with RNG pretty easily It's the same it just instead of just CNG. It's our CNG. So, Yeah, we'll see what happens I mean from the equipment standpoint and then also on the on the policy side at the state level I think those will be some those will provide additional growth areas for the industry as a whole

Tom Raftery:Fantastic. There's a lot of talk these days, Grant, about circular economy. And what you're doing with anaerobic digestion is. Obviously circular, particularly if you were taking a food waste in doing the digestion and then selling the gas back to the companies from whom you bought the food or food waste or who you didn't buy it, who you accepted the food waste from is that A, an angle you're using in selling the, the gas, or in marketing what you do.

Grant Gibson:Yes, absolutely, I mean that's where I was alluding to that earlier around just part of the, what makes us different is that we're able to offer different products in return. So when it comes to the environmental attributes piece of it. So if a customer, a manufacturer says, Hey, I want to send you 20, 000 tons a year, then we're able to create that circularity to where the waste can come to us, produces the renewable fuel, and then from there, We're able to send back not only physical molecules being the get the RNG, but then also the environmental attributes as well. So, yes, absolutely.

Tom Raftery:Okay, cool. We're coming towards the end of the podcast. Now, Grant, is there any question I did not ask that you wish I had or any aspect of this we haven't touched on that. You think it's important for people to be aware of?

Grant Gibson:I mean, not, not off the top of my head. I mean, I think one of the things that we have been doing a lot of recently is community interaction when it comes to When it comes to working with different community organizations to where one of the things that we want is, we want people to understand that, hey, there is this thing called anaerobic digestion and then you could also have a career in it. That's one of the things that we've been partnering with different organizations and across the across a couple of different markets we're in because we want to provide educational tools to where that youth can go and tour and understand, oh, hey, This is what an anaerobic digester does, this is what it produces, and that there is this potential career for me. And, and, and it's much different than anything else that's out there. So, yeah, we've been doing a lot of that. I think that'll just become more and more important to us as we advance our facilities in the different markets. Because one, we want to, We always want to be a good neighbor and a big part and contributor of the, the local community because not only from a jobs perspective, I mean, we're not a large job creator as far as the number of people that will have employed at each facility, but when it comes to the education piece, I mean, and it's just like when I go, when I look back at what I did in commercial composting, I mean, I felt like I was doing like, When the weather was decent out, I was doing a tour almost every single day during the week. And the same applies to our facilities because we want people to understand that hey, there is this way to not send waste, whether it's down the drain, to the landfill, for land application, whatever it may be, that we can actually capture the energy from it and produce this renewable fuel in a way that really just makes sense for everybody.

Tom Raftery:nice, nice, good, great, great. Grant, if people would like to know more about yourself or any of the things we discussed in the podcast today, where would you have me direct them?

Grant Gibson:Yeah, we'd have everybody go to our website, which is www. synthica. com, so S Y N T H I C A dot com.

Tom Raftery:Great. Grant, that's been fascinating. Thanks a million for coming on the podcast today.

Grant Gibson:Yep, Tom, thanks, greatly appreciate you having me on.

Tom Raftery:Okay, we've come to the end of the show. Thanks everyone for listening. If you'd like to know more about the Climate Confident podcast, feel free to drop me an email to tomraftery at outlook. com or message me on LinkedIn or Twitter. If you like the show, please don't forget to click follow on it in your podcast application of choice to get new episodes as soon as they're published. Also, please don't forget to rate and review the podcast. It really does help new people to find the show. Thanks. Catch you all next time.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.

Resilient Supply Chain

Tom Raftery

Buzzcast

Buzzsprout

Wicked Problems - Climate Tech Conversations

Richard Delevan

Climate Connections

Yale Center for Environmental Communication

The Climate Pod

The Climate Pod

Climate Action Show

Climate Action Collective

The Climate Question

BBC World Service

Energy Gang

Wood Mackenzie

Climate Positive

HASI

Climate One

Climate One from The Commonwealth Club