Comic Book Historians

Bill Stout: Illustrator and Creative Architect part 1 with Alex Grand & Jim Thompson

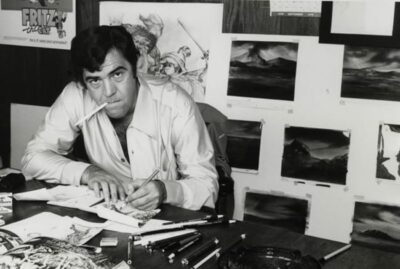

Alex Grand and co-host Jim Thompson interview comic artist, fantasy illustrator and creative architect Bill Stout, discussing his early work in the comic fanzines, bootleg album covers, record label designer, his apprenticeship to Russ Manning on Tarzan and also to Harvey Kurtzman/Will Elder for Little Annie Fanny, Movie Posters, production design and storyboarding for films like Raiders of the Lost Ark. Edited & Produced by Alex Grand. Images used in artwork ©Their Respective Copyright holders, CBH Podcast ©Comic Book Historians. Thumbnail Artwork ©Comic Book Historians.

Alex Grand and co-host Jim Thompson interview comic artist, fantasy illustrator and creative architect Bill Stout, discussing his early work in the comic fanzines, bootleg album covers, record label designer, his apprenticeship to Russ Manning on Tarzan and also to Harvey Kurtzman/Will Elder for Little Annie Fanny, Movie Posters, production design and storyboarding for films like Raiders of the Lost Ark. Edited & Produced by Alex Grand. Images used in artwork ©Their Respective Copyright holders, CBH Podcast ©Comic Book Historians. Thumbnail Artwork ©Comic Book Historians.

Alex Grand: Welcome again to the Comic Book Historians podcast with Alex Grand and Jim Thompson. Today, we’re really excited to have illustrator extraordinaire, Bill Stout, fantasy and dinosaur illustrator, theme-park designer, comic artist, movie storyboard artist, production design artist, the list goes on and on. Bill, thank you for joining us today.

Bill Stout: Hey, glad to be here.

Jim Thompson: Hi, Bill. You are an L.A. guy originally, correct?

Bill: Yes, I was born in Salt Lake City, Utah on the way to L.A.

Jim: Oh, I see.

Bill: My parents were visiting my dad’s family in Idaho and then they started heading back and I popped out in Salt Lake City. Then I was there for a couple of months and then after L.A. Even though I lived all over the world, I have always kept an L.A. base. I would always maintain an apartment or something even when I was working in Europe, or in Canada, or in Mexico.

Jim: And you live in Pasadena now?

Bill: Yup. Pasadena, known for its beautiful craftsman architecture. In fact, I live in a 1913 craftsman house.

Jim: Oh, nice. So, where did you go to school here in L.A.?

Bill: I grew up in the San Fernando Valley in a town called Reseda. It is the hottest part of the San Fernando Valley. In fact, one day, Reseda was the hottest place in the entire world. I think it was over 120 degrees and so I asked my mom for an egg because I always hear about it being so hot you could fry an egg on the sidewalk. So, I fried an egg on the sidewalk.

Jim: I charge extra when I have to go to the Van Nuys Courthouse. It’s terrible.

Bill: So, in the 5th grade, actually, I was in the very first, what they called the gifted program. It was an experiment in California schools, separating out the quicker learners. I learned to read when I was about three and so, I was in the gifted program all through elementary school. One of my favorite teachers was a guy named Elliot Wittenburg. One day, he caught me drawing in class when I should have been listening. Instead of punishing me, he said, “Do you have any more drawings like that?” And the kid next to me said, “Oh, you should see it. He’s got a whole book full of them monsters and dinosaurs.” He asked me if I would bring that book in.

It was like a little cub scout scrapbook that I filled with pictures of monsters and I was just relieved I was not in trouble. So, I brought it in, the next day and he started to assign me extracurricular work involving drawing. He knew I wanted to be a doctor. So, he would say, “Bill, you know I think our class needs a chart of the human muscular system. Could you draw that out for us?” I said, “Yeah, sure.” I would draw that up, the human skeleton, a cross-section of the ear, a cross-section of the eye, and what I didn’t realize is I was teaching myself anatomy. It would have been much easier for him to just punish me, but instead, he made this time investment in me. It’s the reason I dedicated my first book, my dinosaurs book to him.

Alex: Wow. That is a great story.

Jim: Wow, that is great.

Alex: Yeah. I think–

Jim: And that is fascinating about early features, I’ve heard that story.

Alex: You know, a lot of these old medical textbooks from the ’50s, it takes a true illustrative art form to put those together and that is awesome that you basically had a crash course in that. That is awesome.

Jim: So, what comics were you reading at this– when you started being able to read. When did you start reading comics and what were they?

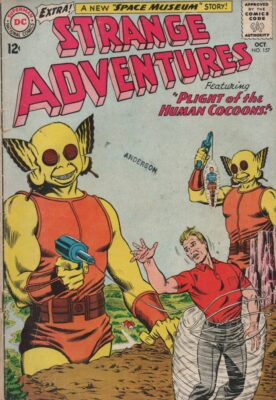

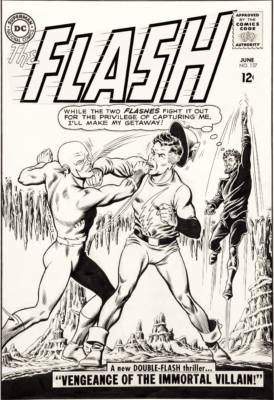

Bill: I started reading comics when I was, I think about 8 years old and I was reading Classics Illustrated because they were the good “safe” comics, you know. And then, we spent one year in El Segundo then moved back to Reseda. I became friends with the guy who had this gigantic trunk full of old comics. I believed it was the trunk that eventually got his bookstore bought and started their whole little mini-empire. But by then, I was reading Archie comics because I like the humorous stuff. I had another friend who had a big stack of Archie comics, but he likes to read superhero comics. He likes Superman and Superman Family and basically, I sort of slowly started to begin reading those, and then I got swept up in the silvery stuff with Flash and Green Lantern.

It was really affected by Carmine Infantino’s work and Gill Kane’s work, and Murphy Anderson’s inking. Around the time I was 14, I believe I met this guy, Fred Romanek in an old bookstore. I was going through boxes of old comics. Then he said, “Hey, do you like comics?” I go, “Yeah!” He lived a couple of blocks away. We went over to his place and he showed me my first fanzine. I have never seen a fanzine before. I think its Rocket’s Class. He proposed we do a fanzine together when he found out I like to draw. He liked to draw too and so we did a mimeo scene called Comics Past, Present, and Future. Put it out and sold all 50 copies.

Alex: Around what year was that do you think, Bill?

Bill: That was, let’s see. Around the early ’60s.

Alex: Yeah. Okay. So, you are about like maybe 14 or 15 years old at that time.

Bill: Well, it is ’62 or ’63, I think.

Alex: Yes. That is great.

Jim: So, what was the subject to the fanzine? What were you guys talking about?

Bill: Oh, it is stuff like should Spiderman join the Fantastic 4? Any kid stuff.

Alex: That’s controversial stuff right there. Yes. Right.

Jim: Oh, that is great. Now, did you only later go back and discover EC Comics, or was that something you had or may add or any of that at that time?

Bill: Well, there is a kid I knew who collected comics at my junior high school and he asked me if I had any EC. I said, “Yeah, I’ve got loads of DC Comics.” He goes, “Not DC. EC.” And I go, “What are you talking about? I’ve never heard of it.” But the name stuck into my mind and then my friend Fred Romanek, I think he showed me my first EC and I was not impressed. It was a special flying saucer issue of either Weird Science or Weird Fantasy or Weird Science-Fantasy. Because it was the special flying saucer issue, it was sort of documentary-like. It’s almost like a news report. And so I end up, “What’s the big deal?”

You know, later I saw more true ECs with the twist ends and all that stuff. Boy, that really hit me. Fred also showed me my very first piece of original comic book art. He had a page, I think it was a Batman page by Jim Mooney who was living in LA.

Alex: Oh, cool.

Bill: And I was blown away because, for one, I had no idea they did them so big. I thought they drew everything in actual size and here are these huge pages. And then, the sleekness to the quality of the inking was just extraordinary. It is the first time I’ve ever seen brush inking close up. I think the inking I was doing back then was probably a ballpoint pen. And so, that changed me. Then, Julius Schwartz used to give away original art. If he liked your letter and Fred wrote a letter to Mystery in Space and he got the most incredible Adam Strange story, I think, they ever did together – Infantino and Anderson. So, I got to see those originals and that really blew me away.

Alex: He sent the whole story. Wow.

Bill: Yes, the whole story. And that was a story that took up, I believe it took up the entire book and it had a one-page that was an absolute classic which was Alanna, Adam Strange’s girlfriend. Full-figured, dripping wet.

Alex: Wow. Beautiful stuff.

Jim: That is just amazing.

Alex: It is.

Jim: So, at what point did you start thinking, “Maybe this is something I’d be interested in doing?”

Bill: That was not until my very last semester of high school. I was a science math major all through school. I was definitely intent on being a doctor. But– which is about 45 minutes north of L.A. and the school system there was horrible. I was not learning anything. In fact, they had a mandatory school spirit. You had to attend the pep rallies. Well, I would ditch the pep rallies and go to the library and try to teach myself because I knew I was not getting taught anything in my classes. But it was sort of like Sisyphus trying to roll that boulder up the hill.

So, my last semester I decided, “Well, you know, you’re going to graduate. You are going to be two years behind everyone else in college. You better think about doing something else.” And I go, “Well, I’ve always liked to draw.” So, I changed my major to art, and then my family was dirt, dirt poor. There is no way they can even send me to a community college. But fortunately, I got perfect scores on my SATs and because of my financial condition and the perfect scores in SATs, the State of California gave me a full scholarship for four years to any university I wanted to go to in the United States. My friends thought, “You can go to Harvard, you can go to Yale, you picked an art school? Are you out of your mind?” Well, I went to California Institute of the Arts, CalArts, which I think at that time was probably the best art school in the country. The head of the music department was Ravi Shankar. The head of the fashion department was Edith Head who won more Oscars than any other costume designer in history.

Alex: Yes. Sure.

Bill: The head of the Illustration Department was Hal Kramer. He was the very first president of the Society of Illustrators. The head of the Animation Department– well, the Animation Department was being taught by Disney’s Nine Old Men.

Alex: Yes, that is right. Those guys.

Bill: Oh, my God. You couldn’t find a better education and so I was really lucky I benefited from that. It was my first time on my own. I lived briefly with my dad. My parents had gotten divorced. So briefly and quickly with my starter jobs, I was making enough money to live on my own, so I moved to Hollywood and have been living there and going to school from Hollywood.

Jim: And those summer job, that was–

Alex: And those Nine Old Men use to make convention appearances toward the end of their lives. I wish I could have caught that.

Bill: Yeah.

Jim: Those summer jobs you had, that was at Disneyland?

Advertisement

Bill: So, yes. I was working in New Orleans Square painting watercolor portraits. We got paid on commissions. So, the more portraits you painted, the more money you make. I was doing over 80 parker to date, just cranking those babies out. It was a fascinating place to be, a fascinating time.

Jim: And while you were at CalArts, did you have any teachers or classmates that we would know that were memorable mentors or partners?

Bill: Let’s see. Well, there are these folks I just named plus, let’s see. My best friend at art school was a guy named Chuck Roblin who did comics for a while. He did comics called Tex Benson.

Jim: Oh yeah. I remember that.

Bill: He turned me on to Heinrich Clay which, boy, that was an eye-opener. Most of the comic stuff, they did not really teach comics at my art school. I was learning all that stuff on my own. But they had a great policy in the Illustration Department. I was an Illustration major. The policy was that if you got any real work on the outside, you can turn it in in lieu of your homework. In my last year and a half of art school, everything I was turning in was a real job. So, I made the transition from academia to the real world absolutely seamless. It is just great.

Jim: Were you still reading mainstream comics, or have you shifted your attention to underground things and stuff like that?

Bill: Let’s see. Oh, gosh. Around 1969– no, no. It was around 1971, I had been doing a lot of artwork for a band. This guy who manages different bands and he also coordinated festivals and built stages for rock festivals. I did a lot of freebie stuff for him and he wanted to pay me back somehow. So, one night, he came over with this fellow he introduced to me. He said this guy was producing a gigantic rock and roll festival, a 5-day festival in Louisiana. And so, they were there to determine what my job would be at that festival.

They fired up a huge fat doobie and about ten minutes later, my friend said, “I know. We need a guy to sit on stage and draw the rock stars while they are performing. Can you do that?” I go, “I can do that!” And so, that was my job. They wanted to do another Woodstock and eventually, the gates came crashing down. The fences came down and turned into a free festival, but it was one of those festivals where it was 24/7. There was not a time when there was not somebody on stage. They played all through the night and all through the day. And I have to meet a lot of fantastic musicians and it was an extraordinary experience. Then I hitchhiked back home from Louisiana up to St. Louis, Missouri, and then St. Louis to LA.

Alex: That’s kind of the rock and roll version of a court illustrator right there.

Bill: Yes, yes. It was cool.

Jim: So, Alex?

Alex: All right. So then, you were talking about the fanzine that you did when you were younger and before ’71 which is where we were kind of at, you also did a Pulp magazine cover called Coven in 1968. How did that come about?

Bill: Oh, yes. We had a job in the bulletin board at art school, and one day there was this posting looking for an artist to do horror, The Fantastic, which is werewolves, vampires and stuff and they’re having a contest to do the first cover for this magazine called Coven 13. So, I submitted three pieces and one of them that was chosen is to be the cover. Their editorial offices were just two blocks from my school. So, I went over to deliver the painting to be shot and I said, “Let me get doing the interiors.” They said, “Oh, our art director is doing the interior.” “Oh, can I see them?” Well, the art was horrible. It looked like elementary school drawings. It was just awful. I said, “How about if I do the interior illustrations, too.” So, I did the covers and all the interiors for the first four issues of the magazine.

Alex: Oh, nice, so you did quite a bit of interior and it is for four issues. That is a lot. And that sounds like it was a natural extension of just your location of the school and the bulletin board.

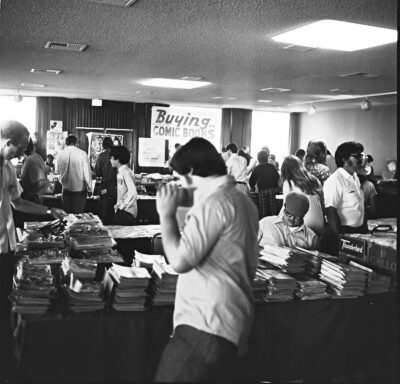

Bill: The location of the school, my passions, my interests, and then that affected me in an interesting way and while I was doing watercolor portraits at Disneyland, I had samples on my easel, each artist did his own samples so the public could say, “Oh, I want that artist,” or “I like that artist’s style.” And so, I was working on a portrait and I hear a voice behind me reading the signature on my portrait. She goes, “Stout. Huh. By any chance are you the Stout that does the illustrations for Coven 13?” I was sort of shocked to be recognized. I turned around and it was a teenage Scott Shaw.

Alex: Oh, wow.

Jim: Wow!

Bill: Scott said, “Would you like to be a guest at the Comic Book Convention in San Diego?” I go, “Sure.” And so, that is how I went to my very Comic-Con.

Alex: Oh, that is cool, yes. ‘Cause Scott Shaw was already part of the early Comic-con. Yes.

Bill: I am one of five people who has been to every single Comic-Con.

Alex: Oh, that is awesome. So now, around the same time, 1971, one of your main mentors in life you would meet him and assist him, Russ Manning, on the Tarzan of the Apes strip. So, how did that come about? How did you meet Russ? How did you get into being trained by him and assisting him?

Bill: I am always a big Edgar Rice Burroughs fan and I have a subscription to this great fanzine called ERB-dom.

Alex: ERB-dom.

Bill: And I began to submit drawings to ERB-dom and an unpublished Burroughs book was found called, I Am A Barbarian. It was the story of Caligula as told by Caligula’s personal slave. So, I was really excited that there’s going to be a new Burroughs book out and Jeff Jones illustrated it. I got my copy and I decided I would do my own version of the illustrations. I did each one in different styles. I did one in the styles of Infantino and Anderson, one style of Frazetta, one style of Krenkel, one style of Wood. Williamson printed for a new assistant and he was a subscriber to ERB-Dom and he saw these pictures. He saw that I was relatively local. He lived down in Orange County which at that time was not that bad a drive. It is about a 45-minute drive. Now it will probably take you a couple of hours. But he called me up and asked if I would meet with him and he asked me if I was interested in assisting him. I was. I was already a huge Manning fan from both this Tarzan comics and Magnus Robot Fighter. And so, I began to drive out, I think, three or four days a week to Russ’s studio down in Orange and I would ink the strips. Everything except the figure of Tarzan himself and I would also color on Sundays. And then, we did three graphic novels together as well.

Alex: So, what sort of technique did you learn from Russ while you were doing that?

Bill: Well, one very important thing is that Russ– when he was in the Navy, that’s where he first got Japanese friends and they have been a gigantic influence ever since. Plus, I always loved Russ’s work and he taught me the importance of meeting deadlines. I loved the way he would create three dimensions within the strip where he placed his blacks. I learned an enormous amount from him plus he also turned me on to– I would say something about how wonderful Burne Hogarth was and he stopped me. He went over to his big flat box. He started showing me all these incredible Hal Foster cards and some Prince Valiant and I was like, “Whoa!” Totally blown away. And so, Foster became a gigantic influence. Whenever I get together with Al Williamson, we’d always joke about how in our work where I was trying to do new breakthroughs and do things people have never done and every time we did something like that, we’d go back to Foster and Foster had done it in the 30s to the 40s already.

Alex: Yes. That is awesome.

Bill: That’s incredible.

Alex: I have read all of the Foster Prince Valiant stuff. I am pretty amazed by some of it. It feels like cinematography like when he is getting attacked by pterodactyls, he is hiding under giant ribs. There is some pretty impressive stuff there.

Bill: Yes. Right.

Alex: So then, now, would you consider your relationship with Russ like a friendship, or was it more like a boss, or was it like a mentor-student?

Bill: It was all of the above. I mean, besides the work, the thing I am most grateful to Russ for is him showing me how to be a good dad. I watched how he interacted with his two kids and I learned so much about being a good parent from watching Russ.

Alex: Wow! That is awesome! So, he had a good demeanor about him.

Bill: Oh, yes.

Alex: Patient demeanor. That is awesome. And then you had–

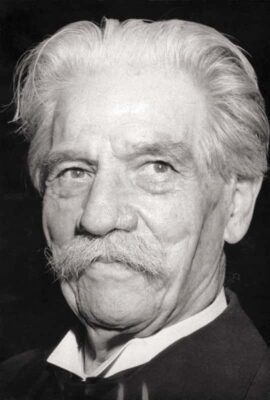

Bill: He also had a sort of Albert Schweitzer-like quality to him, too, in that it pained him enormously to harm any living creature. I remember, I showed up in the studio one day and there is this big line of ants going right across the floor of the studio, and Russ would not spray them, would not do anything. He literally could not even hurt an ant. One time he got termites and it just pained him incredibly to have to kill the termites.

Alex: Yes, that is interesting. So, even to insects, that is a huge amount of compassion. I have to admit. Now, why did you end up leaving Russ? What were the circumstances of not working for him anymore and then going to your next thing?

Bill: Well, I got this job working at a rock festival.

Alex: Oh, the rock festival. There you go.

Bill: So, I was gone for a few weeks and I was young and dumb. I just kind of sprang in on Russ that I was leaving for a while and he was like shocked. He’s like, “Wait a minute. I’m not going to have an assistant for a couple of weeks?” So, it started him looking for someone else. But I came back and I continued to work on it but by that time, I started doing my own stuff. I was working for a Cycletoons and Cartoons doing comic book stories for Petersen Publications.

Alex: There you go.

Bill: And then my illustration career started to really hit, and I started doing movie posters. At that time, that was the biggest money you could make in illustration was movie posters.

Alex: There you go.

Bill: And so, Russ and I separated–

Jim: I wanted to ask you about– in ’72, you transitioned over to working with Kurtzman too on Little Annie Fanny. Is that right?

Bill: Right, yes.

Jim: So, tell us a little bit about that. How that came to be and your relationship with Kurtzman and with Elder.

Bill: Sure. I became a huge EC fan due to Frank Frazetta. I was collecting every Frazetta comic I could find, and I found out that he did several things for EC inking Williamson and did a story on his own and did the incredible Weird Science-Fantasy 29 cover. So, my goal was to buy every Frazetta comic and so I got every Frazetta EC. When I get the Frazetta EC’s, well, look at this great Williamson stuff. So, well, now I had to get all the Williamson ECs, and that was taking me– I was acquiring a lot of science fiction EC – Weird Science and Weird Science-Fantasy and Weird Fantasy. So, I sent all these great Wally Wood stuff like I got to get all the Wally Wood stuff. Well, you can see how the collection expanded to the part where, “Well, I think I need a dozen more issues now that I got all the EC New Trends.” So, one of the latter things that I was turned on to was Mad and Panic, and Willie Elder stuff. Willie Elder had this incredible ability that is so rare which is he can do a drawing that will make you laugh even if you do not understand the context of the story. It is just funny art.

Alex: Yes. It is funny, anyway. Yes.

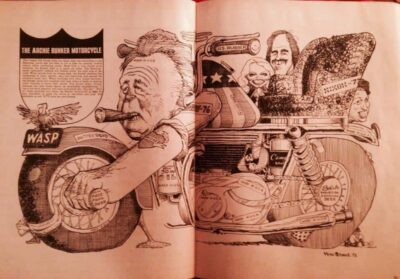

Bill: Yes. It is funny, anyway. And so, I did a story for Cycletoons that was a tribute to Harvey Kurtzman, Wally Wood, and Willie Elder called Motorcycle. When it was supposed, I sent off copies to all three guys. And I got a letter back from Kurtzman asking me if I would like to come back to Houston to work on Little Annie Fanny with him and Elder.

Advertisement

Alex: Nice.

Bill: I was like, I was just through the moon. It was incredible.

Jim: Wow.

Bill: So that was the first time I ever went to New York and it happened to coincide– that was 1972 so it happened to coincide with the very first EC Convention. So, I got to meet all of my heroes in that one weekend.

Alex: There you go.

Jim: So, speaking of your heroes, which ones, out of the EC artists, which ones really spoke to you? What were your favorites?

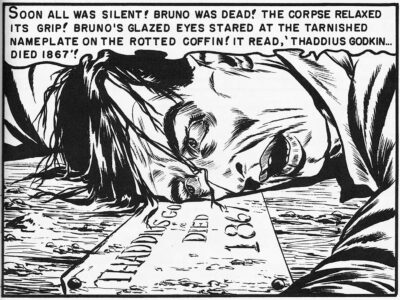

Bill: Frazetta, Williamson, Wood, eventually Graham Ingels. Graham Ingels had this extraordinary ability to even his so-called normal people look like there is something wrong with them. Just really. It sort of gets into your spinal cord, the creepiness of his stuff.

Alex: It does.

Bill: I learned a lot about storytelling from Krigstein. George Evans became a good friend of mine. Williamson and Krenko were good friends. Reed Crandall, a big influence.

Jim: Oh yes. He’s great.

Bill: I got to meet Reed when he was working in Al Williamson’s studio. Al invited me to spend the weekend at his place. He was sharing a studio with Reed Crandall. I got to meet Reed Crandall. That was pretty awesome.

Alex: So, this was all around that convention in ’72, that EC convention that you met all these guys?

Bill: Yes.

Alex: Wow.

Jim: What about Davis?

Bill: Oh, Jack Davis? Jack, I came to his stuff later in life. I liked his comics, but I wasn’t nuts about him. When the things that really knocked me out by Davis was when he drew the Universal monsters and those monster trading cards. That stuff is just extraordinary. I still got all that stuff. Oh, and his album covers were phenomenal. I was also really impressed by him because I had read that he was making over a million dollars a year and I said that – “That’s a worthy goal.”

Alex: Yes. A nice goal for sure.

Bill: So, my first thought was, “Okay, how does he do it?” Well, for one thing, he works fast, “Okay. How can I teach myself to work really fast but maintain a high quality of the work?” Work fast but not losing quality. And so, that became the real goal of mine. So, I became a very fast artist and I was doing a Jack Davis.

Alex: Yes, because you can draw an ankylosaurus in five minutes. Yes, for sure. That is awesome.

Bill: The first thousand are the hardest.

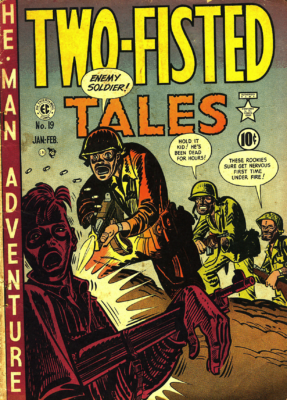

Jim: That’s really fascinating. All of those EC influences. Were you into the Kurtzman war books too? The Sovereign and all of the people that were doing those?

Bill: I was definitely into Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat. Those had a big influence on me. They were the very first war comics that were anti-war. They were realistic. It did not glorify war and that was an extraordinary thing plus it was also happening at the time we are still involved in the Vietnam war, too. When I was working for Kurtzman, research became essential. I remember I was working on a Little Annie Fanny page that required a fire hydrant. So, I just drew a fire hydrant in there. He goes, “Bill, how do you know that it looks like a real fire hydrant?” And I go, “Why? I just kind of remember it.” He says, “Let’s go outside.” We went outside and we found a real fire hydrant. And I saw everything I have drawn wrong. That became this thing with – I caught the Kurtzman curse. It really slows me down because I got to research everything because I cannot have anything that is not accurate. But I think it pays off at the end. You end up with stuff that is set at just a higher level of quality than you would have if you just made everything up.

Alex: So that attention to like realistic detail comes from Kurtzman and then the push for other mediums and to draw fast comes from Davis, right? These are like various elements that you absorbed and that is great.

Bill: Yes. Definitely.

Jim: Was Kurtzman– was he hard to please?

Bill: I would like to– I like all that Elder–

Jim: Was he hard to work with in terms of that?

Bill: No. He was– I mean, he was really demanding but, you know, I was used to that, working with Russ. Russ was demanding and it was always for a higher end. It is always to do the best possible work. There is no harm in that.

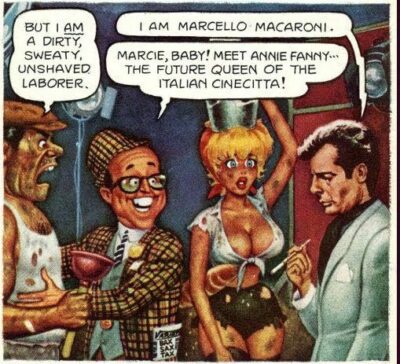

Alex: What was the main function for Kurtzman and Elder that you did, and did it help them save time? What was the successful assistance that you gave?

Bill: Okay, so, the reason they hired me is Kurtzman saw that I could duplicate styles. So, he figured I could duplicate his and Willie Elder’s style and Hefner was complaining that they were not producing enough Annie pages each year. And so, the idea was I would be slipped in between Kurtzman and Elder. The way it would work is Harvey Kurtzman would write three stories and then he would draw them up on 8 1/2 x 11 sheets and then send them off to Hefner. Hefner would approve one and it would come back and then Harvey would– let’s see. He would begin drawing the pages full size.

One thing that really shocked me was I had not realized how incredibly tight Harvey’s pencils were for Annie as I was used to seeing his finished work which seems deceptively simple and this was anything but simple. They were really detailed, and he would do that in a series of layers until, finally, the final layer was the last pencil page. Then he would give that to me. I would make a home-made carbon paper because the carbon paper that you would buy in the art supply stores had a residue that we did not want. And so, I would just take a soft pencil and take a sheet of paper and cover it with a soft pencil.

Then I would use that to transfer Harvey’s pencils to a nice, clean sheet of illustration board. And then I would redraw everything that Kurtzman had done and corrected any anatomical errors I saw. And then while I was doing that, Kurtzman was taking Xeroxes of the story pages. And then he water-colored them. So that gave me my color schemes. Then using those, I would start to build up transparent color on the penciled art. And when I was about half-finished, then I would take it over to Will Elder. And Elder would do the finishes. And when the page is finished, it would go to Kutzman. And Kurtzman would lay a tissue over it. And he would make 300 corrections–

Alex: Oh, no.

Jim: Wow.

Bill: On that one page.

Jim: Wow.

Bill: Then it goes back to Elder. Elder would make the corrections. They would go back to Kurtzman. Kurtzman makes a 150 and more corrections. Go back to Elder. Elder makes the corrections. Go back to Kurtzman. Kurtzman makes about 50 more corrections.

Jim: Wow.

Bill: Elder would do those. And then the page was finished except for going to the letter. And I said, “Harvey, my God. No one’s going to see these little corrections. Why on earth do you that?” He said, “If I didn’t do it, Hefner would.”

Jim: That’s what I was going to ask you. Could you have any interactions with Hefner? And what did they think about working with Hefner?

Bill: Whenever Harvey would visit in LA, he would take me to the mansion. So, I would meet Hefner at the mansion. But it was frustrating for me because Hefner did not understand Harvey’s sense of humor. Often, Hefner would rewrite Harvey’s dialogue, because he did not understand Kurtzman’s penchant for catchphrases. And he would replace it with really stupid, dumb dialogue and really killed the humor. But Hefner was a frustrated cartoonist. And this was his way of expressing himself as a cartoonist.

Kurtzman really wanted to work in films. And the way that Hefner kept sort of Kurtzman dangling, he kept promising him he could direct a Little Annie Fanny movie. Every time Kurtzman was threatening to leave, Hefner would bring that up.

Jim: Ah, I never heard that. Had you heard that Alex? That is interesting.

Alex: No. Uh-uh.

Jim: But it never happened?

Bill: So, I was only on this trip for a couple of stories. And Kurtzman took me aside and says, “Bill, you’re too creative for us. We’re not getting any speed by having you working between us.” In my arrogance, I was adding jokes, and I bought cakes and stuff instead of just doing the job. And they needed just somebody to do the job and be invisible. And that was not me.

Alex: Yeah.

Jim: But it was a big influence working with you in the future after leaving that job, right?

Bill: What’s that?

Jim: I said Kurtzman was a big influence on the work that you did after you left that job. You could see a lot of Kurtzman and Elder in the subsequent stuff.

Advertisement

Bill: Oh, absolutely. And, in fact, I think my first or second day of working with Kurtzman, Harvey said, “Bill, you’re going to learn a lot here. You may not realize it at that time. But years from now, it will bubble up when you go.” “Oh, yes.” And, boy, was he right. I’m just still doing stuff now where I go, “Oh, yes. I can see Kurtzman–”

Alex: I see some of that influence of Kurtzman-Elder in the book you did with Leonardo DiCaprio’s dad. I feel a lot of that. But it is like your Rock ‘N’ Roll essence is in it, obviously. But I can see their influence, I feel.

Bill: Yeah.

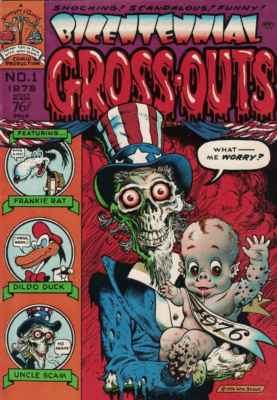

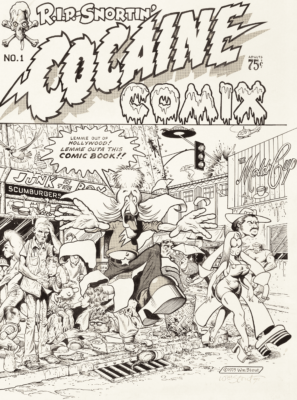

Jim: Well, in all those covers that you did, shortly after that, some of the underground stuff, the Fear and Laughter cover and Weird Trips and Cocaine Comix, you see a lot of that humor and a lot of the kind of echoing back to Mad and to Kurtzman and to general. But talk a little bit about that period, what you were doing in terms of the underground comics.

Bill: Sure. I mean, one of the things I really connected with Kurtzman and Elder is we both have a subversive sense of humor.

Jim: There you go.

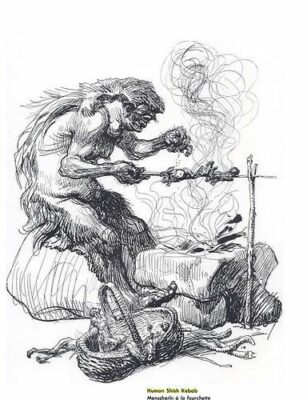

Bill: And that tends to run through almost everything that I do. Even some of my Antarctic paintings, I will put in little things that just should not be there.

So, I think it was Jim Evans who– I met him. He was the designer of that rock festival in Louisiana. And then he was the guy who showed me my first Zap Comic, my first underground comic. And I think it was the one with Joe Blow, the Robert Crumb story. And it just blew my mind. I read that, I said, “Oh, my God. Comics can do anything now. Anything.” Oh, it was wide open. And it was a revelation. It was just, absolutely, incredible stuff that Crumb was doing, Griffin, Robert Williams – all those guys – Spain Rodriguez just blew me away. And I knew that I had to be a part of that.

And so, I started drawing my own underground comics. Initially, I did some stories for Jim Evans. He used to put out an underground comic called Dying Dolphin. But my stuff, it just really did not fit with the theme of the book. But I kept the pages. And, eventually, these were printed elsewhere. But, yes, the underground, that really did it for me.

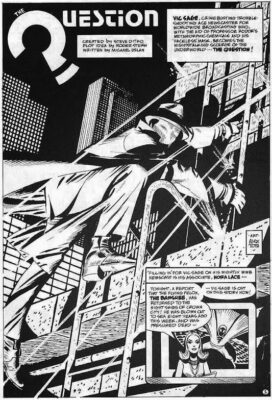

Jim: Oh, that is great. Before we move on to Alex and talking about some of the Rock ‘N’ Roll and Heavy Metal, we were talking about EC artists. There is one that I wanted to ask you about that didn’t do very much with EC. But I know he was a favorite of yours. What about Alex Toth? Any thoughts? Did you know him?

Bill: I knew Alex really well, went to his house a lot. I was introduced to Alex by Bob Foster, at that time he was probably, Alex’s best friend. And in my early day in doing comics, I kept hearing about storytelling and how important that was. And I had no idea what people were talking about. And they kept saying, “Yes, one of the best storytellers in the business is Alex Toth.” So, I just started to buy his stuff and look at it even though I didn’t understand what was going on. Through osmosis, I began to pick up some of his storytelling techniques and stuff. And so, he became a really important influence on me even though at the time when I first discovered him, I had no idea what I was looking at. I was much more impressed by the guys with slicker-inking styles back then. But eventually, Alex’s work hit me like a ton of bricks.

Jim: He’s a favorite of mine.

Alex: And that is interesting, the use of blacks because Dan Barry with that slick New York line and you have Alex Toth which is a little more rugged. But the storytelling and the shading that Noel Sickles influenced, it is a really different usage of blacks. So, it seems you really keep an eye on that, on the use of blacks.

Bill: Yes. And the way he would spot the word balance too. That was really incredible. And the way he would even spot the sound effects. If there was a throbbing engine sound, that would go crawl across the bottom of the panel. It’s just amazing. I learned a lot, a lot, from Toth.

Alex: That’s awesome. Okay. So, then, all right. Now, you mentioned Jack Davis who made a lot of money and was very successful. And one of the things he did was he went beyond comics and to other mediums. You, of course, did the same. Tell us how you got into doing the covers for the bootleg albums. So, there is Trade Mark of Quality record label. There is some very famous, easy style Who covers you did. Tell us how you got involved in that.

Bill: Sure. Well, I am a huge music collector. I have got, I think, over twenty to thirty thousand albums and many thousands of CDs and stuff. And there was Capitol Records in Hollywood. On the first Sunday of each month had a record swap meet in their parking lot. And people would sell used albums. This is pre-CD. So, this is all vinyl and stuff.

I had a favorite record shop called Record Paradise on Hollywood Boulevard when I was living in Hollywood. I always checked in with them. And there was this new phenomenon called Bootleg Record Albums. I think the first one I saw was the Great White Wonder. It was a Bob Dylan bootleg. And then the second one I saw was Liver Than You’ll Ever Be. It was a Rolling Stones bootleg. And these were White Album covers with the name of the albums stamped in blue up in the corner. So, there was no art or anything involved. And you could buy these on the street from people. Or you could buy them, actually, in some of the record shops as well. And that Rolling Stone reviewed Liver Than You’ll Ever Be because it turned out it was a better live album than the official released by the Stones. It is an extraordinary show.

And back then it was a lot looser. You could go to a concert and bring a Sony tape recorder and tape the entire show if you wanted. You could get right up the stage, take photographs with the players. It was all a lot looser back then.

So, I’d just been to a Led Zeppelin concert and I saw all these people taping the show. So, I knew, probably, there is going be a bootleg of that concert. And that was one of the best concerts I have ever seen. So, I was waiting every day and checking at Record Paradise to see if a bootleg was out yet. And one day I walked in, and there it was. And I looked at it. And the art was so crappy. And out loud I said, “Oh, man, the band deserves better than this. I wish somebody would get me to do a bootleg record album covers.” And a guy tapped me on the shoulder. And he said, “You want to do bootleg record album covers?” I go, “Ah, yes.” He goes, “Okay. Meet me at Salem and Las Palmas, Friday night, at 6 o’clock. Be alone.”

Alex: I love the shifty stuff. Yes.

Bill: Yes. So, I thought, “Well, that’s interesting. That is already a seedy part of Hollywood,” really horrible part of Hollywood. So, I showed up at six o’clock, Friday. And this coop drives up with smoked windows. And the passenger window side goes down a crack and a piece of paper comes up. And I take it and it says, “Rolling Stones Winter Tour.” And there is a list of songs. And a voice inside says, “See you in two weeks. Same time. Same place. Be alone.”

Alex: I love that.

Bill: I did my first album cover for them. It was sort of a tribute to Robert Crumb’s Cheap Thrills. I love the idea of each song having its own illustration and also having caricatures of the band members on the cover as well. So, I did that. I remember the bootleggers so they could trust me that I could meet them in person and stuff.

The name of the company was Trade Mark of Quality, TMQ. And so, I began to hold them to that name. I kept pushing for more and more quality in the product that they are producing. The first bootleg record album covers were printed on 8 1/2 x 11 sheets. And they were slipped in between the cover and the shrink wrap. So, they were not actually printed on the boards themselves. Eventually, I got them to print the covers on the actual boards of the album covers. And then I pushed them and got them to do the first color cover which I think was a Bob Dylan Melbourne, Australia cover where Bob’s hanging in a kangaroo pouch.

So, it just kept expanding. And one of my favorite bands in the whole world was The Yardbirds. And they wanted to do a The Yardbirds bootleg. And I found out that Keith Relf, the lead singer of The Yardbirds, was living just over the hill from me because he is putting together a new band called Armageddon. And so somehow I got his phone number and called him up and said, “Look. We’re doing a two-album bootleg of really rare Yardbirds material, live recordings, European B-side, stuff like that.” I said, “If we paid your rent for this month, would you consent to do an interview?” Basically, the interview was I would play the album for him and he would just free-associate whatever came to his mind and what was going on when they are doing that back then.

So, we did it, it was a long interview, but we made semi-legitimate bootleg album cover. One of the bootleggers was with me. And he took photos of Keith. And those photos appear on the back cover. And then the front cover, I did a sort of Arthur Rackham style illustration of the Yardbirds where each guy was a different bird sitting on branches of a tree. The Yardbirds had the extraordinary good luck to have as their first lead guitar player Eric Clapton, their second lead guitar player Jeff Beck, and their third lead guitar player Jimmy Page. I got to see the very last Yardbirds concert. It was in L.A. at the Shrine Exposition Hall. I got backstage and I got to meet Jimmy Page, Keith Relf, Chris Dreja, and Jimmy McCarty. And I found out, Jimmy told me, he says, “Well, the band’s breaking up.” I went, “No. You are my favorite group in the world. You can’t do this.” Keith and Jimmy McCarty formed the group called Renaissance. And then Jimmy Page, he kept the Yardbirds. And they changed into Led Zeppelin.

Alex: Nice, yes. That is right. One quick question before I go to the next question. Did Graham Ingels ever say that Arthur Rackham was an influence on him? Did it ever come up in a conversation? I have wondered that because there are some similarities I feel when I look at both of their stuff.

Bill: Yes. I have never heard that anywhere.

Alex: Yes. Just my–

Bill: If I had, it really would have stuck in my head, too. Because Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac were both huge influences on me. Still working what I call a Dulac-Rackham style.

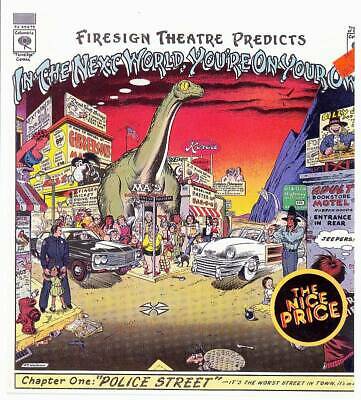

Alex: Oh, that’s right. So now, we were talking a little bit before the show that when you did a couple of the Firesign covers that that got you into the more legitimate album cover work. And one of them had the Next World, You’re on Your Own, had a big dinosaur right in the middle. Tell us about that stage of your life there.

Bill: Sure. There was a–

Jim: And about Firesign also ’cause people may not know what that is, about Firesign Theater.

Bill: Sure. Yeah. Firesign Theater were four guys. And they have made comedy albums. But their comedy albums were like no other comedy albums you have ever heard in that you could play them over and over and hear new stuff each time. They are really heavily layered with comedy and information, I call them an oral version of Kurtzman and Elder’s comics. Kurtzman and Elder would have what I recall eyeball kicks. It is a little, tiny jokes filter all throughout in addition to the main story that was being told. The Firesign Theater did the same thing but orally. They had heavily layered sounds. And, oh, gosh, almost throwaway lines and stuff that you go back later, and you listen to it again. And, oh, there’s always new stuff to find.

So, my pal, Dave Gipson, he was a comic book dealer and an original art dealer. And he put out the very first Spirit reprints. And then he got permission to put out a collection of a Firesign Theater fanzine called The Mixville Rocket. It was something that they produced for their local neighborhood. And so, I did the cover for that and the guy saw the cover. And it is so reflected the kind of humor that they were doing. They started wanting me to do their album covers.

So, the first album cover I did for them was, In the Next World, You’re on Your Own. Now, I was fighting Columbia, though. Columbia, their record label did not want to have me do a cover. For one, they had never heard of me. I was a total unknown to them. They did not know if I could meet deadlines. They did not know if I knew anything about the proper way to design an album cover. But after I turned in, In the Next World, You’re on Your Own, they were so delighted they began to give me lots and lots of work. That was my introduction and breakthrough into the legitimate record album world.

So, In the Next World, You’re on Your Own, I designed it. So, I’d had two front covers. No matter which way it was in the bin, you were looking at the front cover. And the record company loved that. They were delighted that I was smart enough to know, to always put all your information, the title of the album and who does the album at the very top. Because these records are in bins and as people are flipping through, the only thing they could see is the very top. And so, I had already done that. They were relieved and began a great relationship with Columbia and CBS.

Alex: And then from ’75 to ’77, you were Art Director for a Rock ‘N’ Roll magazine named Bomp! Is this all kind of part of the same involvement in the music world as it just kind of grows into this?

Bill: Well, that was sort of an up growth of the bootlegs. Greg Shaw was the original publisher/editor of bootlegs and magazines in a way that was more contemporary, it was hipper, more visual. He contacted me. We had worked together. He had supplied me with some of the rare records for like Who’s Who which was a double album of The Who with really rare B-sides and singles and stuff like that. In fact, John Entwistle who saw a copy of that album had not realized how much unreleased Who stuff there was. And he put out a legitimate version called ODDS & SODS. And then when they did the CD version of ODDS & SODS, The Who contacted me to license one of my Who bootleg record album covers as the picture disc for the CD. So that was pretty awesome.

Alex: That is.

Bill: Yes. So, let’s see. Oh, the other thing with the Firesign is I did my very first movie with them. They did an album called, Everything You Know Is Wrong, and they decided to make a film out of it. And so, it was sort of the reverse. Usually, you shoot the film and then you dub everything later. They already had the soundtrack. So we just mimed to the soundtrack. And I built the props for the film and was an extra in a party scene. And that was my first intro to filmmaking.

Alex: Oh, that’s awesome. And then one more question before Jim does the next section. So how did you go about contributing to Heavy Metal magazine around this time, the mid to late ’70s?

Bill: My regular publisher, Byron Preiss, had commissioned me to do a story for The Illustrated Harlan Ellison. And I did this story called, Shattered Like a Glass Goblin.

Jim: Sure.

Bill: To promote the book, The Illustrated Harlan Ellison, Byron licensed my story to Heavy Metal. And so that maybe one of the first, if not the first, American contributor to Heavy Metal. I was getting Heavy Metal in its original form, Métal Hurlant, the French Magazine. And so, I was really super well aware of what the European cartoons were doing, because I had a monthly subscription to that magazine.

Alex: Oh, that is great.

Jim: I know you are a Moebius fan, Giraud fan. But who else were you really interested in, in that period?

Bill: Oh, gosh. In that period, oh, Victor de la Fuente. He did Mathai-Dor and some other stuff. He turned out to be a close friend of Williamson’s. When I was in Spain working on Conan the Barbarian in Madrid, every Friday at six o’clock, all the local comic book artists would get together at Totem, a local comic book shop. The owner would lock the doors and we just hang out and chat and stuff for about an hour. Then we go down the street or block. There was a café where the owner was nuts about comics. He had a big table for us and he served us free hors d’oeuvres and drinks all night long. It was, absolutely, incredible. There I got to meet Carlos Gimenez who I consider the Spanish Eisner. I mean, this guy’s-

Jim: He’s great.

Bill: His stuff is so compelling that I had a book called Paracuellos and another one called Barrio. And I translated them word by word because the images were so compelling, I had to know what the story was. But Carlos is an amazing, amazing artist.

Advertisement

Jim: Oh, that is great. Alex, anything else on that? Or we are ready to move on to–?

Alex: Yes. Let’s go to Bakshi.

Jim: Okay.

Bill: Oh, and I should also mention Richard Corben, gigantic influence. One of the guys, he probably had the greatest technical knowledge of any comic book artist work in the business. He bought his own machine to make his own color separations, which is enormously expensive.

Alex: Wow.

Bill: But that way, he was able to doctor the coloring at the most intense color which is what he wanted for in his comics.

Alex: I see.

Bill: Yes. I met Richard. I had a funny experience meeting Richard. There was a guy working on Conan the Barbarian before I was working on Conan named Bob Greenberg. He called me up, he says, “Bill, do you know Dino De Laurentiis has just hired Richard Corben to do the storyboards for Conan? And they put me in charge of showing him a good time and entertaining him while he is in L.A. Can we come over to your studio?” I go, “Richard Corben? My studio? Hell, yes. Bring that guy over here. I want to meet this guy.”

And so, he brought Richard over. I began to pull every rabbit out of every hat, “Hey, check this out. This is a Peruvian Mummy Head I have got. Here is an Egyptian Mummy Hand I’ve got.” If I can get more than two words in a row out of him, I was being really successful. He was just sort of standing there while I am showing him all the stuff. He is got a big smile on his face. He is got his hands in his pockets. And he is sort of rocking back and forth on his heels. And then after about two hours, I ran out of stuff to show him. And I thought, “Well, I guess, we just didn’t connect, ’cause he never said anything and stuff.” And they took off.

Two months later, I picked up the latest issue of Creepy magazine and there is this mummy story by Corben in it and Corben wrote a little intro. He said, “I was recently hired to storyboard, Conan the Barbarian Movie. It didn’t work out, in fact, I had an incredibly miserable time in Los Angeles except for when I got taken to Bill Stout’s studio. That was the best day of my life. That was absolutely fun. Oh, my God. I had so much fun. He showed me all this really cool stuff. He showed me this mummy head. And that’s why I created this mummy story.”

Alex: Yes. Well–

Bill: I was like, “Right. Could have knocked me over with a feather.” I had no idea.

Alex: That’s funny. I guess he contained it and expressed it on the paper. Yes.

Jim: That’s a great story.

Bill: I remember I asked him and I said, “Do you ever your wife as a model?” He goes, “Nope. That’s too small.”

Alex: Yes. He definitely knows his art definitely. Yes.

Jim: So, let us talk about your work with Ralph Bakshi. You did the poster for Wizards. Did you do anything else with that or just the poster?

Bill: Well, at that time, I was working for this little ad agency in the west Los Angeles part of L.A. They called me up to say, “We got something different for you this time. It’s a movie poster for an animated feature.” I said, “Oh, great. Are you going to show me the film?” “No. You’ll do a nicer poster if you don’t see the movie.” And I thought, “Well, that doesn’t speak well of this film.” Anyway, I came and take up the job. And I think I did 12 roughs. And they picked one. And I went to finish on that. And that became the poster for the film.

And then four days before the release of the film, I got a panicked call from the ad agency. He said, “The studio thinks your poster is too scary. It is going to scare kids and they’re not going to come to see the movie.” And I said, “Kids love scary. What are you talking about? Kids, I think, scary is great.” And he got, “No. No. You got to redo the poster.” I go, “The film’s coming out four days from now. What do you mean to redo the poster?” He said, “We have our printer waiting for you. All you got to do is do the new art. And get it over that printer.” And I said, “I’ll do it today.” I made all the changes and stuff. I took the skulls and bones out and the flies and then replaced it with mushrooms and flowers and stuff like that.

Alex: You sweetened it up a little bit.

Bill: Yes. And believe it or not, I finished it that day, got it over to the printer, and they had that in the theaters for the release of the film.

Alex: Nice.

Jim: Did you go see the film after that?

Bill: I have never seen the film.

Alex: Oh, really?

Jim: Oh, that is interesting.

Bill: Yes.

Jim: You weren’t curious at all. That’s fascinating.

Bill: It is a lot of people’s favorite film. It is also a lot of people’s most hated film. But as I aged and as I grow, the people who hate that film have sort of disappeared. There is a whole batch of people who are just nuts about that movie.

Jim: So, you never met Bakshi?

Bill: I did not meet Ralph until after the poster was published. He wanted to meet the guy who did the poster. So, I drove over to his studio and that was the first time I met Ralph.

Jim: Ah. What did you think of him?

Bill: He’s a character, bigger than life character. I had lots of friends who had worked for Ralph. They had some pretty wild tales about the guy.

Jim: Alex?

Alex: Yes. So, out of curiosity, is it that you didn’t see it because you felt like, there’s a lot of Wally Wood and Vaughn Bodē influence but they weren’t credited? Or was there some reason that you still have not seen it to this day?

Bill: Um, let’s see, how can I say this in a nice way? Well, I am not a huge fan of Bakshi’s films. I hated Lord of the Rings. It is two hours of talking heads. So many people had warned me against seeing Wizards. Ralph gave me a copy. I have got it on Blu-ray. But I just have not had the interest.

Alex: The interest – a lack of interest. Okay. So now– and this is a little bit more of some musical stuff. How did you come about designing the original Rhino Records label in 1978?

Bill: Oh, as I said I was a big Yardbirds fan. I think it was like a local free paper. There was an article written on The Yardbirds by Harold Bronson. I knew of a Fred Bronson who was involved in comics fandom stuff and I got them mixed up. I thought Harold was Fred.

And so, I wrote this really nice letter praising The Yardbirds article that Harold had written. And Harold wanted to meet me. And we met. He was going to UCLA. And he was working as a clerk at a shop called Rhino Records in Westwood along with his pal Richard Foos. And Harold and I hit it off because we are both The Yardbirds fans. Then I got a call from him a few months later. They thought it would be a great idea to see what would happen if they made one of their own records. So, there was this freak character named Wild Man Fischer. He was hustling you on the streets of Hollywood. And he says, “Sing a song for a dime.” And if you get him ten cents, he would make up a song on the spot for you. Well, they have got Wild Man Fischer in the backroom of Rhino Records with recording machines. He spontaneously came up with the song called Come to Rhino Records. And I think he did one of the songs that ended up on the B-side.

Harold calls me up and says, “We’re going to put out our first record and see what happens. But we need an image for the label. It is called Rhino Records. Can you do us a label drawing?” And so, I created Rocky Rhino. That was on the very first rhino record. To their amazement, their record sold out. So, they did another one. They put together a group called the Temple City Kazoo Orchestra and they did Led Zeppelin’s Whole Lotta Love all on Kazoos. They put that out, that sold out.

Alex: Nice.

Bill: That was the launch, the seeds– the very seeds of Rhino Records which became the best-re-released company in the world. And eventually, Harold and Richard quit Rhino, the records, the shop because they’re having– they went full time with the record company and eventually, Richard bought this old record shop that he used to work at. And then had me redesign it.

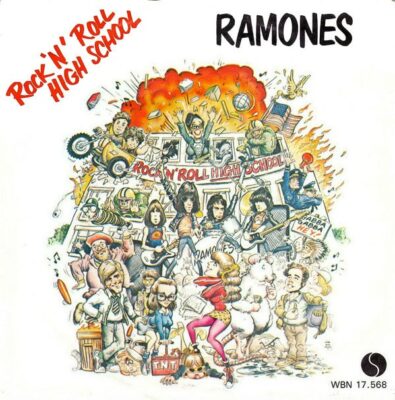

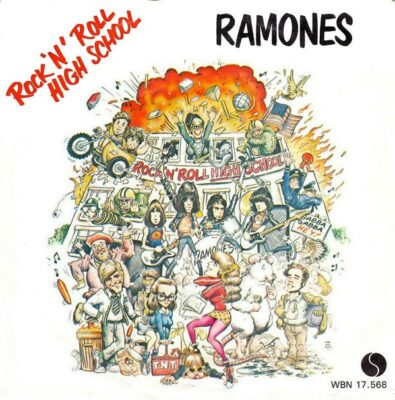

Alex: Oh, nice. So, now you did the poster for a Rock N’ Roll High School with the Ramones in 1979. The Ramones themselves were big comic fans. Were they involved in the idea of you doing the poster? Had they given you feedback on the poster? How did that come about?

Bill: That came about because let’s see, I was doing movie posters, that was my main gig back then and well, I’m trying to think if Rock N’ Roll High School was my first– I think Rock N’ Roll High School was probably my first poster for Roger Corman. I love working for Roger because typically when– the agency I did the most posters for was Steininger & Associates, Tony Steininger. And typically when I worked for Tony, a film would come in and I’d do a couple of dozen roughs, then I do a few comps, black and white comps. I do a color comp. So, by the time I finally got to the final poster, I had drawn it about 40 times. But that is the thing that the public is going to see. That is where all of your energy and juice has to go into.

And, it was really difficult to not be burnt out from all of the redrawing and everything. Well, Roger Corman did not want to pay for all those roughs and stuff. I could show him a sketch in my sketchbook and he said, “Oh, Bill, go to finished.” And it was great. So, I could put all my energy into the finished art without having to redraw it 20 times. I am not sure why they chose me for Rock N’ Roll High School. Maybe they had seen my Firesign Theater stuff. I am not sure. But I got the call and I showed Roger my rough. He said, “Go to finish.” And at the time, the film was being edited by Joe Dante and the film’s director Alan Arkish at a little street that was just a few blocks from my apartment. So, I came in to see them and to get photographs of all the people in the film because I wanted to put them on the poster. And walking into that room was like walking in on two kids who’d just been given the keys to the candy shop. They owed each other working in the film business and making movies and stuff. So, I picked up a whole bunch of reference photos from them and then did the poster. Roger did give me one instruction. He said, “Bill, you can do anything you want as long as it looks like Animal House.”

So, I drew it. It looks, basically, like the poster for Animal House. And they are still making the film while I was doing the poster and stuff. Well, it turns out that my favorite taco and burrito place was also the favorite taco and burrito place of the Ramones. So, I run into them all the time whenever I go to have lunch or dinner. So, I met the guys that way. I told them, “Yeah, we’re doing a poster for your movie and stuff.” They are fine men. They are cool guys.

© 2020 Comic Book Historians