Montana Voice

Stories and more. Season 3, with original music, is a reading of 'The Lie and the Aether,' an early version of what became the popular novel "Paper Targets" by Steve Saroff. Other seasons include stories that were originally traditionally published, interviews, and other interesting listening materials — highly recommended.

Montana Voice

11 - Luke's

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

Pascal tells a story about a drunk ballerina and an arsonist, and Luke's bar in Missoula. Enzi realizes that he is also going down a bad road. Then Enzi visits Kaori in jail.

Visit MontanaVoice.com for more information and to listen to additional episodes.

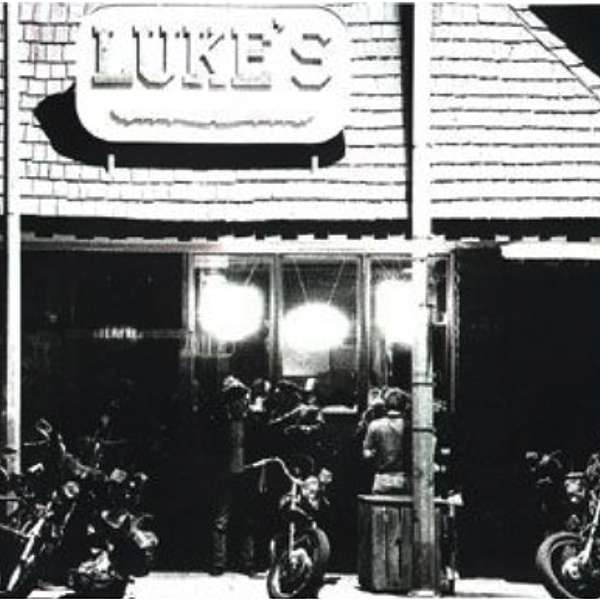

Luke’s from the novel, The Aether and the Lie by Steve S. Saroff

Tsai ordered me to Seattle and then hung up on me. I was tired of the aether and the wires. The networks and the phones. I wanted to see her again.

I drove to the jail, parked, and went to the front door. There was no window, only a locked door in a brick wall. I rang a buzzer, and a voice from a speaker in the wall above me asked me what I wanted. I talked to the speaker, told them Kaori’s name, and said I wanted to see her. The voice told me that visiting hours were only on the weekends unless I had a court order to visit with her now or unless her lawyer accompanied me.

I went back in my car and drove downtown. I turned off Front Street and drove into the large parking lot by the river, where I had seen Pascal’s truck several times. It was there, and I saw Pascal sitting in the front seat, reading a book. He smiled and nodded when he saw me. He got out of his truck and said, “Haven’t heard from a Fella in a while. Wondered about him.”

I told him that I was looking for him and guessed he would be parked down here.

“Only leased lot downtown,” he said, “land that no one wants, yet. Probably be a hotel soon.”

I asked him what he was reading, and he held up the book. “If Not Now, When,” by Primo Levi.

“Good?” I asked.

He shrugged, “Words,” and he tossed the book into the cab’s back seat and asked, “What is a Fella thinking about now?”

I asked him if he knew anything about Kaori, about what was going to happen next.

He said he didn’t know anything other than what he had read in the paper.

I told him that I had stopped reading the news.

He said the newspaper hadn’t written anything that we didn’t already know.

I told Pascal that I wanted to talk with her, and had just been to the jail, but they said I would have to wait until Saturday to see her, or go in with her lawyer. So I asked him if he knew who her lawyer was, and Pascal told me that he assumed that it was one of the public defenders, and he told me where their offices were.

We were both standing and leaning against Pascal’s truck, looking towards the back of the buildings on Front Street. Pascal pointed to a new building close to us, the back of a restaurant. He said, “That used to be Luke’s bar. Before it was burnt. A fella remember the place?”

I told him no.

He said, “Luke’s. There was a pizza place in the back. The newspapers said that a grease fire started in an oven.” Then he asked, “A Fella want to hear something never told before? A Fella want to share a secret?”

I answered, “Sure. I’m already holding a few of them, one more won’t hurt.”

Pascal nodded, then said, “It wasn’t no pizza fire. It was someone hiding in the back closet, and then he piled up cardboard pizza boxes and empty beer cases in a corner, and he lit it.

“I found out ’cause last year he got busted for a repeat DUI. A family member called me from someplace, my number in google search, and then wired me money, had me bail him. Sad case. At the hearing, they sent him to Warm Springs for 60 days of treatment, and he hung himself there. I figure I can tell a fella what he told me.”

Pascal pointed back to where Luke’s had been, and he went on, “I used to go there all the time. Live music most nights of the week. You sure you were never in there?”

I told him no.

“A Fella missed the best part of Missoula. Anyway, Luke’s looked like a tough place. Harleys in a row outside. Barmaids with tattoos. Spit on the floor, that kind of place. But it wasn’t bad, it was music and great dancing. Ace Wheeler’s talent show case. Banjo Bill Wylie. Eric Forrest. Good dance place.”

I asked him if he brought the Norway girl there, and he laughed and said, “Luke’s was way before ‘Nordsky’s time.”

“Anyway,” he said, “College girls would come with their boyfriends. And all these old-time, broke-down cases, they would mostly stand by the bar watching the girls. Quiet, hard-drinking. You see memories drowning in their eyes.”

He looked at me and continued, “Client who killed himself, he tells me that he was at Luke’s every night drinking until he couldn’t hardly walk. Then he would get in his car and drive and get his DUI’s. He tells me, though, that he didn’t use to drink at all. He tells me that the first time he walked into Luke’s, nearly twenty years ago, a girl asks him to dance. He said she was, as he put it, ’a perfect beauty.’ You must understand that my Client is what I would just call ’a perfect ugly.’ Twisted, pitted, face. No ‘sim-it-tree.’

“And this ‘perfect beauty,’ was a blind-drunk-drinker he tells me. He tells me a story. Tells me that she was fired from some big-city ballet that was doing a performance at the ‘U’. Fired for being drunk. Fired and then she goes straight downtown and picks up my Client. She even tells him that she wanted to know what someone with a ‘rough face’ was like. Tells him that she was tired of ‘pretty people.’ She tells him that. But he doesn’t care, ’cause now he is in love.

“He had a job, and a rented place, and she stayed with him for a while. Each night the two would go to Luke’s. Dance, and drink. He said she loved dancing almost as much as she liked her drink. But then, no explanation, she dumped him. Then he finds out that she was shacked up with someone else. Then a while later, someone else again. She stayed in Missoula, though, and she kept going to Luke’s. She kept dancing and drinking. My Client said he also kept going there, to Luke’s, sitting at the bar, and would stare at her and whomever it was she was dancing with. Said he was waiting for her to come back to him. He said he even kept an unopened fifth on the bathroom counter and a full ice cube tray in the freezer said she liked drinking whisky with ice in the bath.” Pascal shook his head, and continued, “Then, my Client said, she stopped coming into Luke’s, and that he never saw her again.

“Anyway, she was gone ’bout twenty years, but my client kept drinking every night up there,” Pascal waved his arm towards where Luke’s used to be, “said he kept going into Luke’s each night, sitting, and watching the girls. Said he if he drank enough, he would see her face in all their faces. See the strangers become his ‘Beauty.’

“Then he burnt the place down. And he didn’t get caught. Told me that he had to do it to save his life. But it didn’t help, he kept drinking and told me he kept seeing her face even when he slept. Probably saw her face too clearly when he was taking treatment at Warm Springs. Finally, ended it all with torn bedsheets and a light fixture.”

Pascal sighed, “I figured he gave me his life story. Gave it to me alone. Now I’ve shared it with you.”

Then he added, “Guy walks into Luke’s his first time, and a friggen Ballerina falls into his arms. His first mistake was meeting her, and his second was thinking it would happen again.”

Pascal looked at me and asked, “Is that going to be your story? Gota say, a Fella has the same look. Haunted. Looking for more of the same bad....” but before I could answer, he smacked the side of his truck and said, “Hell. I see the same look in my eyes when I shave. Same look in most everyone’s eyes. Looking for lost chances.” Then he pointed at me, his finger lightly touching my chest, and said, “A Fella just happens to have his one locked in the slammer for keeps. That must hurt. Come on, let’s go find out which one of the lazy snakes is hers. Your turn to drive.”

Pascal got in my car and gave me directions to the public defender’s offices which were nearby. We went inside. The receptionist knew Pascal, and the two talked about the weather for a while and how cold the coming winter would be. Then Pascal asked the receptionist if he knew who was handling the ‘Japanese artist murderer.’ The receptionist answered, “Clint Eulichol, for now. You want to talk with him? I think he was about to go visit with clients, but you might be able to catch him if you hurry,” and he pointed upstairs.

We went up a flight of stairs to a small office with an open door. Inside was an albino man. His hair was typing-paper-white, and his eyes were red. He looked up at us as we knocked on his door, recognized Pascal, and said hello to him. He glanced at me and then spoke to Pascal, “Don’t be asking for specialized exceptions. I am booked solid in an extravagant manor.” He said this with pauses between his words like he is fishing with worms for big ones.

Pascal answered, “Aw, Clint, this is just a friend,” and he introduced me and said, “This Fella is the sorry-assed fool who bailed ‘Kaori Y’, double murder, out the first time. He was hoping you could spend some of your valuable time with him.”

The lawyer looked at me and then at Pascal. He shuffled folders on his desk, then looked up at a clock and said, “There isn’t truly a purpose, a point. She doesn’t want representation. She has presented no defense in any manner. However, being that we live in a death-penalty state, she must have council.” He sighed and said, “I am yet temporary. There will be someone from Helena taking her files from me soon. Besides,” and he looked up at the clock again, “My entire day is orchestrated by obligations. No time at all for un-scheduled encounters.”

I explained that I just wanted to talk briefly with Kaori and had been told I would have to wait until the weekend unless her lawyer accompanied me. So I asked him if there is any way to get me in that afternoon. “Any chance at all?” I asked.

Eulichol again looked at the clock. Then he looked at Pascal and said, “In private practice I would be able to charge for breaking my schedule.”

Pascal asked, “What would a ‘private practice’ lawyer be able to charge for such a thing?”

Albino answers, “It would be a three-hour disruption --- and lawyers who handle capital cases get at least three-hundred an hour.” He sighed again, shuffled more folders on his desk, and then said, looking at me, “But then, I am simply a ward --- if you will --- of the state. Much the same as all our clients become. I must be off.”

Eulichol stood up, put on a heavy coat, and turned the collar up to go above his ears. He also took a large, felt cowboy hat from the coat rack and put that on too.

We left his office and went downstairs with him. He paused by the steps and put on a pair of dark sunglasses, and said, “I’m heading out towards the jail...” and he paused.

Pascal looked at me, then back to the lawyer, and said, “This Fella here might be heading out that way too. Tell you what, wait for him just a tad before you buzz yourself in. Fella might just be interested in talking with you then.”

The lawyer nodded, then said, “I have realized that I have forgotten something of need. I will be about ten minutes delayed,” then he turned and went back inside.

Pascal touched my shoulder and said, “Come on,” and we walked back and got in my car. “Is it worth nine-hundred bucks for you to see her today?” Pascal asked, “Mr. Sleaze is giving a Fella the chance to get to the bank. I know. He does things like this. It is the reason he still works for the city. He makes money doing almost nothing at all.”

I told Pascal that I didn’t need to go to the bank, that I had enough cash, and yes, it was worth it. Pascal nodded, then said that I should give the money to him and drive to the jail and wait. Pascal told me that he would give the nine-hundred dollars to the lawyer.

I took ten one-hundred-dollar bills from the wad of money in my coat pocket and gave them to Pascal. I said, “Keep one.”

Pascal removed one bill from what I had handed him and put the rest into his coat pocket. Then he handed me back the extra hundred and said, “I never take this sort of dirt. Reason I am broke all the time. I might facilitate it a bit, but I don’t want to profit from any of Eulichol’s sleaze. He would be hiding from the sun even if he did have pigment. The freak show shines right out those eyes. Bleak.” Pascal got out of my car and said, “I will walk back to my’ Office.’ A Fella can drop by later.” Then he headed back towards the public defender’s office.

I drove to the jail. Second time in one day. The road was spotted with ice, and the sky was the color of depression. At the jail, I went and waited by the door with the buzzer, and after a few minutes, the lawyer’s car pulled into the lot. He got out and walked up to me, whistling. I just nodded at him, and he said, “I examined my schedule and found I am actually supposed to visit one K Yamaktoo today.”

“Imagine that,” I replied, and then I said, fast, “I want to be alone with her. You understand that, right?”

He shrugged, said, “I shall ask the jailor in private to determine the appropriateness of your private request. I shall pass on the information you have indicated that you have personal affairs to discuss.” Then he pressed the buzzer, and he and I were inside in an air-lock room that stunk of unwashed feet and guilty sweat. Then we were buzzed into a long hallway that was blocked by a security checkpoint. The albino talked briefly and quietly with a jailor and filled out some paper. Then we both emptied our pockets. Keys and wallets, and phones went into envelopes.

We walked through a metal detector and were escorted by the jailor Eulichol had spoken with. We were led through another electronically locked door and into a hallway lined with metal doorways. I had assumed that the jailer would have us wait in some kind of meeting room and then would have seen if Kaori had wanted to see me, but instead, we were brought straight to her. While we were walking, the lawyer explained that he would wait out in the hallway while I visited with Kaori. The jailor said, to Eulichol, “While she is in this place, you make most of the rules, I’m just an escort. I’ll be outside the door.” Then he added, “She’s on suicide watch anyway. Camera sees and hears everything. The desk will be watching and recording anyway.”

We stopped at a numbered door, and the jailor used a pass card key, something that looked like a hotel keycard, and opened the door. He didn’t knock. He didn’t ask permission.

Kaori was alone in a cell about five feet wide by ten feet long with a high, ten-foot ceiling. There was a bed, a sink, and a toilet built into the wall at the end. Kaori sat on the bed, cross-legged, hair in front of her face, sketching in a notebook. She didn’t look up. The jailor motioned me in and said, “Mash this button if you need attention. Otherwise, I will be back in fifteen,” and he pointed to a big black button near the door, and then I was locked in, alone, with Kaori.

For about half a minute, I stood quietly and didn’t say anything. She was wearing a jail uniform that looked vaguely like bright pajamas. She was also wearing slippers like the ones she had on the night I bailed her out. I could hear her uneven breathing, a quiet gasping which was in time with the motions of her arm. She was crosshatching and filling in an area in her sketchbook with a rubbery-looking felt tip pen. Finally, I said, “Hello, Kaori.”

She stopped drawing and looked up. I had expected her to be angry or indifferent, but instead, she happily exclaimed, “You!” and dropped the pen and pushed the notebook away. She jumped off the bed and came and hugged me. She said, “You visit me!” She stepped back and asked, questioningly, “You take me out? You bail me?”

I shook my head no. I said that she could not be bailed out. I explained that I was just there to see her and that we didn’t have much time.

She nodded and pointed up to a small, recessed video camera that was mounted up by one of the ceiling’s corners and said, “They watch all time. I know. So shamed. Light never goes off.”

I touched her hand and said we should talk. I stepped around her and sat on the bed, but she stayed standing. She saw the discoloration that was still across my face, the bruising from where she broke my nose, and she asked, “Face hurt? So sorry. Not you I hit. Not you.”

I answered, “I’m fine.” Then I said, “No, I am not fine. I am, how did you say it once, ‘I am so Sad.’ “

She said, “You remember everything. But must not be sad for me. I be sad for me. Me my own lonely. Me my own time.” Then she clapped her hands together and said, “I have idea. Play game. I tell you happy word. You tell me happy word.”

I asked her what she meant, and she replied with, “Plum. So good. Dark plum.” She closed her eyes, she moved her tongue slightly out of her mouth, over her lips, she said, “So --- how you say --- dee-lee-us.” Then she opened her eyes, looked at me, and said, “Now you. Give me happy word.”

“Delicious,” I said, “Yes, plums are delicious.” She was looking at me, honestly waiting for me to say a ‘word,’ a single word. Again, like the first time I had seen her, I had no idea what to do or say. I was not even sure why I was there. I wanted to confess to her about the money I had buried. I wanted to tell her about Tsai. Or I wanted to ask Kaori about herself, about everything that I would otherwise never know about her. Sweet drink. Plum. A game. A child. No good word. No single word. I picked up the sketchbook, another school notebook with lined paper, and I asked, looking at her, “Do you need other notebooks, ones without lines?”

“No!” she answered, “Those not happy words. Game is happy word! Then I talk.” She came over and took the notebook from me and held it. “Say happy word now. Give me happy word.”

I was quiet for a few moments, and then I said, “Moon.” She smiled, and I said, “Full moon on a clear night.” I looked at Kaori, and she was still smiling, so I went on, “Stars. No city lights. A clear sky.”

“And day will be clear too?” She asked, nodding, “Day good like night?”

“Yes,” I answered, “Sleep in the day,” I pointed at the narrow slit of a window up by the ceiling at the far end of the cell, “With sun from the window to make your dreams bright.”

She said, “You not so good with one word, but you ok with more. I say my next good words. Two words. Game sister and I played. Now two words. Watermelon. Round.”

As I looked at the folds of her prison clothing, no happy words came to me. I was remembering her feet and her hands and remembering her breath on my face. I asked, “Kaori, do you need me to help you understand anything? I saw your checkbook once. Your money, does it come from your family? Does anyone in Japan know you are here? You should let someone hire you a good lawyer.”

She looked at me with panic. She said, “This not good words! Bad words!” But she went on, she said, “Tell no one. My shame.” She bowed her head, then she said, “You look.” She opened the notebook in her hands. She showed me drawings, turning the pages one at a time, not saying anything. All were beautiful. None were violent. I asked again about the lined paper, and she shook her head no. She said, “No bars here,” she motioned to the walls and to the door which had no doorknob, to the slit of a window, “They tell me this jail not real one. Other jail will have bars. Paper has bars. Bars are right. Lines are bars,” and she moved her hand along the lined paper in the notebook.

I tried to explain that she had not had a trial yet, but that after the trial unless she were innocent, she would be moved to the state prison.

She said, “I know. I had my trial with knife. I failed.” She looked up at the video monitor and said, “You tell them I no kill self. You tell them nothing to see. You tell them I failed.”

I started to talk again, but she interrupted me and said, “No. Now you just look.”

I find moments without looking. Memories. Like books on a shelf, there is a scattered chronology, a disjointed stratum. Storms followed by windless gray. But then there are the peaks – a soft evening rain in a bright sunset sky with a rainbow arching over the darkening east. Then the rainbow doubles, the new colors reverse, and the center of the partial circle becomes connected with a perfect and invisible line from the sun behind my head. Does it matter that she was a chance moment? Do the thickness of the spines on the cluttered shelf matter? Do the physics of light explain the beauty of color?

We have no choice other than to become veterans of time, but is it wrong to hold onto the sparks even if they still burn?

I can say, “On this day, I woke up, worked, ate, and slept.” I can say, “During this month, it was the same as the last.” But can I ask, can I say, “I want more?”

Kaori said, “One love.” Did she sleep with me to burn her memories? Her “one love,” whom I never met and who is now dead. She used me. I knew. I know. I didn’t care. I don’t care. I want more.

“You just look. You no touch.” I remember her saying this to me in New York. I was kneeling next to the hotel bed, and she was lying on top of the covers. She had turned crosswise so that she faced the wall of glass and the city-scape night. She said, “You just look. No touch.”

Then, in the jail cell, I was paging through the notebook that she handed me. In the drawings, her hands were always touching him. His shoulder. His arm. His face. And she was always looking at him. In those drawings, though, he was never looking at her. He was looking away. He looked down, or he looked past the steam rising from a cup of tea.

She had killed her ‘one love’ when he no longer would touch her, and she had also killed the person he had been touching. And she used a jailhouse felt-tipped pen and on ruled paper --- with lines that were the bars that her cell did not have --- and showed me images that were already becoming the sparks that would keep burning.

I pointed to a sketch with the teacup, which had a Kanji character underneath it, and I asked, “What does this say?”

And in the jail cell, while Kaori knelt on the floor next to where I was sitting on the bunk, she put her hand on mine. Then fast, she took it away. She looked up into me --- right into me --- and said, “Spring.”

Then she told me, “Met in Spring. I seventeen. He soldier. He visit Tokyo. We Karaoke. I go visit in Okinawa. Train all night. Morning I make tea for him. He tell story about home in Montana. Says come to Montana.”

I closed the notebook and tried to give it back to her. But she said, “No. You take. You look. You understand art.”

Then the door to the cell opened, and the jailor was there telling me I must leave. I stood up and tried to hug her, but she turned and faced the back wall of the cell. She said, “No touch. Ever again. Everything gone. You go now. Forever.”

Walking through the hallway lined with the numbered doors, out of jail, Eulichol, the albino lawyer, nodded towards the notebook I was carrying and asked, “You get your money’s worth?”

I said, “Shut up,” and he smiled like he was used to hearing people say this to him all the time.

Luke’s from the novel, The Aether and the Lie by Steve S. Saroff

© 2021 Steve S. Saroff