Drayton Hall

Drayton Hall

Landscape Audio Tour

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

INTRODUCTION (0:00)

Welcome to the landscape of Drayton Hall. I’m Amber Satterthwaite, Curator of Education and Museum Programs, and I’ll lead you across the landscape today.

Take your time and feel free to pause the recording whenever you’d like to look around, take pictures, or stop for a break. I’ll be describing things to you as you walk, and I’ll reference your landscape map, which will keep you on the tour path. Your map also includes some images to enhance the tour and assist with wayfinding. I’ll refer to some of those images as you walk. Watch your step as we tour the grounds.

When you’re ready to begin, start walking on the gravel path to your right. Shortly, you’ll see another path, on your right, between two black metal markers. Turn onto that path. Stay between the markers as you walk, following the route on your landscape map. Stop walking when you reach the Grand Oak tree at the end of the path, labeled part one on your map. While you walk, I’ll tell you about the site’s early history.

This area was occupied by Catawba, Cherokee, Creek, Kiawah, Kussoe, and Yamasee prior to European contact. Archaeology performed onsite has recovered pottery and other evidence confirming the presence of Native Americans as long as 800 to 1400 years ago. Its location on the Ashley River made this an excellent place for fishing, and Ashley River Road, which you drove on today, was a well-established Native American trail by the 18th century.

Native Americans were forced to adapt to rapid changes when English colonists began to settle here, bringing enslaved Africans with them. Wars, European and African diseases, and enslavement combined to quickly reduce the Native American population, and major changes occurred across the Lowcountry landscape. To understand the extent to which this particular landscape was modified, let’s briefly discuss the early years of the Carolina colony.

It was 1670 when English settlers established Charles Town on the Ashley River, and the city was moved to its present location between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers a decade later. Tracts of property outside the city were sold or granted to colonists. Many of Charleston’s early residents came from the Caribbean island of Barbados, another English colony. Charleston retained strong ties to Barbados—slave laws in South Carolina were even modeled on strict Barbadian slave codes. Charleston became the primary mainland port in the transatlantic slave trade. By the early 18th century, this had become the only mainland colony in which the Black population was greater than the white population.

Europeans and Africans first inhabited this property around 1680. About the same time, the Drayton family established a plantation next to this one, known today as Magnolia Plantation. John Drayton’s mother, Ann, was still living there when John purchased the plantation that he named Drayton Hall in 1738. Some of the earliest enslaved residents at Drayton Hall included the Bowens family, whose descendants resided on the property through the early 20th century. I’ll introduce you to members of the Bowens family in more detail later.

PART ONE: GRAND OAK (3:20)

By now, you’ve reached or are nearing the Grand Oak. As you admire it, look around you. This landscape was developed for inland rice cultivation in the late 17th century. Rice, a staple crop in many West African cultures, became a key cash crop for Lowcountry planters, who benefited from enslaved Africans’ rice-growing expertise. Knowledge of rice cultivation was so important to enslavers here that it became common for them to seek out enslaved people from areas of Africa where rice was culturally significant. Enslaved Africans from diverse backgrounds and cultures who were brought to this area developed a language known as Gullah or Geechee, which blended African and English linguistic influences. Gullah was one of the languages spoken at Drayton Hall.

The swampy terrain of this property and its proximity to the Ashley River played a key role in rice production here because growing rice required the ability to routinely flood and drain fields. For this purpose, enslaved Africans constructed ditches, reservoirs, and embankments, and some of them are still visible today. The labor-intensive work of planting and harvesting rice, irrigating fields, and maintaining the plantation’s manmade environment was done year-round. In short, labor associated with rice production required specialized knowledge and skill.

By the time John Drayton purchased this plantation, inland rice cultivation was falling out of favor, and more planters focused efforts on tidal rice cultivation. This motivated planters like John Drayton to purchase vast amounts of land along tidal tributaries.

The ponds you drove between on your way in to Drayton Hall were components of the inland irrigation system. When John’s son Charles took ownership of Drayton Hall, he wanted the ponds turned into piscatories and had them filled with fish to catch. Enslaved men used large nets called seines to catch trout, bream, and warmouth, which Charles called by their colloquial name, mawmouth. You’re welcome to walk the perimeter of the ponds, but be careful because this is a natural habitat for native alligators and many species of snakes.

As I mentioned, when John Drayton bought this plantation, the property had previously been developed for two earlier European owners. It was advertised as having “a very good dwelling-house, kitchen, and several out houses, with a very good orchard.” Archaeologists located a portion of that earlier plantation house underneath the northwest corner of Drayton Hall, which is the front left corner from your current vantage point. During John’s lifetime, Drayton Hall grew from 350 to 660 acres and functioned as the home seat of his vast commercial plantation enterprise. I’ll explain this a little later.

The features you see on the landscape today reflect many time periods. When planning the landscape in the mid-18th century, John had modifications made, but he decided to retain some trees that were already growing, including this Live Oak.

Let’s continue this discussion as we move toward the mound in front of the main house.

PART TWO: MOUND (6:53)

Begin walking toward Drayton Hall and the raised mound in front. Stop when you reach the mound.

As you walk, the reflecting pond is on your right. In the late 19th century, the Draytons had this pond created, which perfectly reflects the façade of Drayton Hall on the surface of the water. It’s a great place to take a picture. The mound where you’re headed was built from the spoil dug to make the pond.

On your left, you’ll see a well. It’s a 20th-century addition to the landscape that fed pump heads next to the main house and the privy, but there were many wells on the property over time.

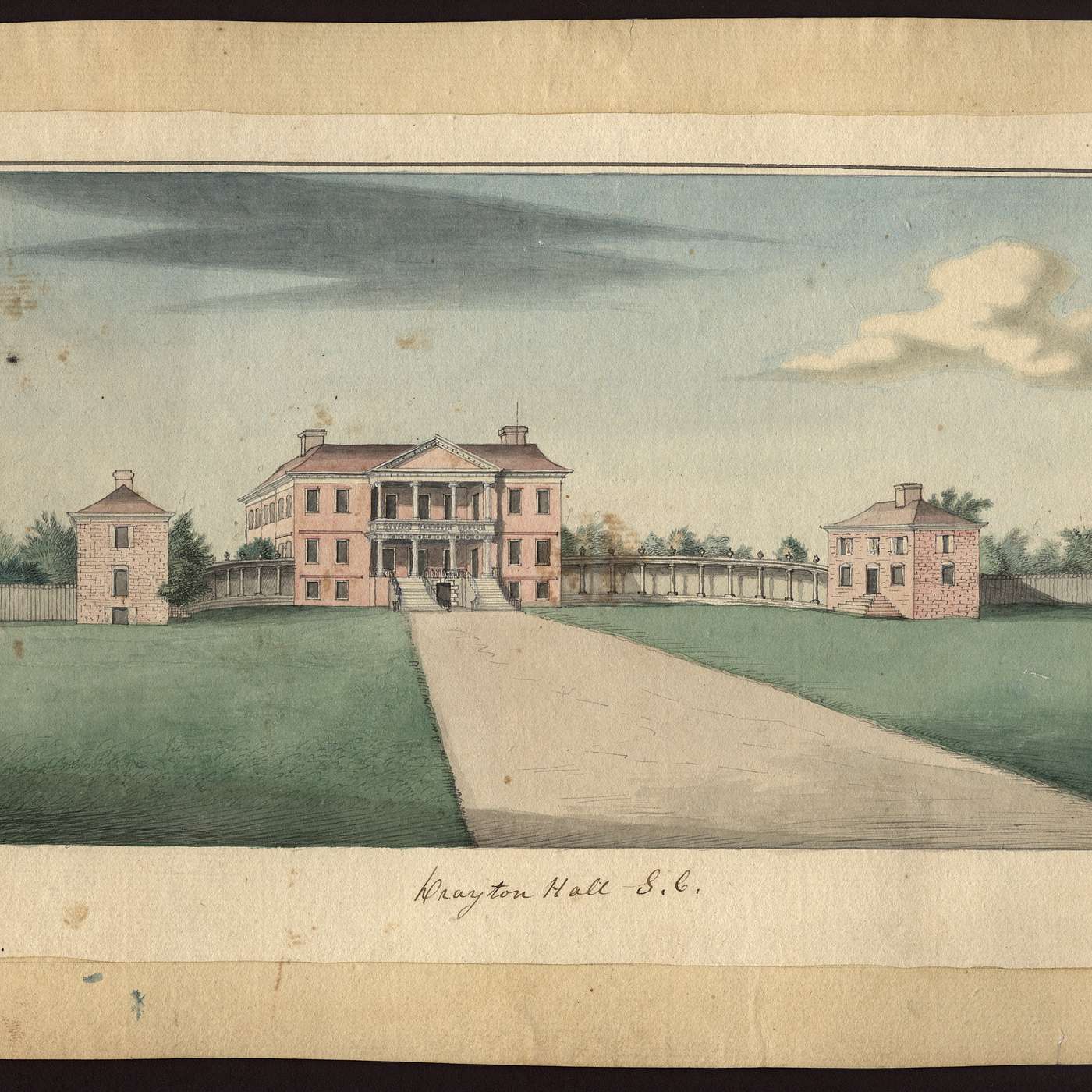

Look at the watercolor painting on the front of your map. Drayton Hall was built as a 5-part Palladian-style villa, with two-story brick buildings, which we refer to as flankers, on either side of the main structure and connected by colonnades. The main house, along with its slightly angled flanker buildings and concave colonnade, created a dramatic, theatrical view. We don’t know exactly when the colonnades were removed, but it may have happened during the Revolutionary War when British and American forces occupied the property and the house.

The flanker buildings were taken down around 1900, but their locations are outlined in brick on the landscape. As you can tell from the photograph in image C in your map, the flankers had fallen into a state of disrepair. That may be a primary reason why they were dismantled.

In the 20th century, members of the Bowens family recalled their ancestors Caesar and Ellen Bowens living in the flanker that stood on your left side following the Civil War. Caesar was born into slavery at Drayton Hall and lived on the property his entire life. The Bowenses had 14 children.

The exact purposes of the flankers are undocumented, but they were designed with careful attention to detail. Measurements show that despite appearing to be perpendicular to the main house, each flanker building was angled outward by 4 degrees, creating an optical illusion that made them appear to be at perfect right angles to the main house. Their designer, very likely John Drayton himself, understood that if they had been constructed at 90-degree angles, they would appear to turn in slightly. A similar knowledge of optical illusions was used on the portico columns, which bow outward slightly to create the illusion that they’re perfectly straight.

PART THREE: HISTORIC PATH (9:39)

Now, let’s move toward the back of the main house. Follow your landscape map to walk around the right side of Drayton Hall. Stop when you reach a magnolia tree with benches underneath. I’ll share more details with you as you walk.

Commodities produced at Drayton Hall over time included lumber, cattle, and pigs. Most of the woods on the property today were cleared fields in the 18th century. Charles Drayton, the plantation’s owner from 1784-1820, recorded the production of crops including corn and cotton, but most of his wealth was generated by rice production undertaken by people enslaved on other plantations. The Draytons hired overseers and additional white employees who directed and supervised work performed by enslaved laborers on all their plantations, including Drayton Hall. Those employees lived on the property with their families.

Remember, when you reach the benches under the magnolia tree, stop and listen a few moments.

Referring back to the watercolor painting of Drayton Hall, you’ve now entered the part of the property behind the flankers and colonnade—an area that people approaching Drayton Hall could not see from the front lawn.

During the American Revolution, John Drayton fled from Drayton Hall ahead of British troops who were moving through the area, and he died not long after leaving his home. Just before the Siege of Charleston, thousands of British soldiers convened at Drayton Hall and camped on the very ground you’re walking on now before crossing the Ashley River and moving toward the city.

By the end of the war, Drayton Hall had served as a headquarters for both British and American soldiers. It’s possible that John’s widow, Rebecca Perry Drayton, was living at Drayton Hall with their young children during a portion of that time. We hope future research will reveal more about how Rebecca, the Drayton children, and enslaved people here were impacted by military activity on the site. After the Revolution, Rebecca sold Drayton Hall to John’s son Charles.

In the late 18th century, French author and educator Francois-Alexandre-Frederic duc de la Rochefoucauld-Liancourt wrote that Drayton Hall’s landscape was “better laid out, better cultivated, and better stocked with good trees” than any other he had seen. He continued: “In order to have a fine garden, you have nothing to do but to let the trees remain standing here and there, or in clumps, and to plant bushes in front of them, and arrange the trees according to their height.”

Historian David Ramsay wrote during Charles’s ownership of Drayton Hall that the gardens here were “arranged with exquisite taste.” Most of all, Ramsay was impressed by the “elegant and concentrated display of the native botanic riches of Carolina, in which [Charles] has succeeded to the delight and admiration of all visitants.” Ramsay also mentioned that Charles’s daughter, Maria, was a capable student of botany.

From your vantage point, you have a view of the area they were writing about. Much of the landscape has changed, but as you continue your walk, I’ll point out what’s left of the landscape they saw.

Now, make sure you’re facing the back lawn, with your back to the benches under the magnolia tree. Begin walking to your right and walk toward the woods. When you get closer, you’ll see what remains of a historic path.

As you’re walking toward the path, I’ll remind you to watch your step as we make our way across the landscape. You’ll encounter some tree roots and potentially uneven ground. You may also notice artifacts on the ground surface, especially if it’s rained recently. Help us protect the site by leaving artifacts in place. Please do not pick them up. Instead, take a picture of the artifact and let a staff member know where you saw it, and we’ll let one of our site’s archaeologists know. We appreciate your help protecting the archaeological record.

By now, you’re approaching the remnants of the path I mentioned. It will be on your left as you face the woods. Let’s start walking toward the river.

Look at the 18th century map in image D in your landscape map. You’ll see that this path was here even then. Let’s start following the path.

As you walk along this serpentine path, you’re walking on an elevated terrace, placing you above the woods and vegetation on the right side. Since the enslaved labor force had cleared the woods for agriculture or construction, this path granted the Draytons and their guests a pastoral view with the Ashley River in the distance.

PART FOUR: HA-HA (14:20)

You’ve reached part four on your landscape map: the ha-ha. The ha-ha, which looks like a ditch, will be visible on your left as you approach it. When you pass the palmetto tree, you’re almost there. If you aren’t quite there yet, you can pause the tour until you’ve arrived.

A ha-ha like this was intended to keep animals away from gardens without disturbing sight lines. Ha-has were key in picturesque English landscapes when sweeping, uninterrupted natural views were desired. The term ha-ha comes from the exclamation “a-ha!” and was coined by 18th century landscape designer Capability Brown. This ha-ha has been present since at least 1791 and was featured on a map made that year (image D in your map).

When you’re ready, continue walking the path.

You’re nearing a large oak tree. Because the walking path goes around the right side of the tree, we believe this tree may be one of those John Drayton chose to retain on the landscape. Not far from it is a red buckeye, one of the trees Charles wrote about in his diaries.

Keep walking along the tree line toward the river. You’ll pass some exotic and fragrant shrubberies likely planted during Charles’s period of ownership.

Charles Drayton was a product of the Scottish Enlightenment. After completing studies in England at Oxford, Charles studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. There, he took classes taught by John Hope, a Scottish physician and botanist. Hope’s botany class emphasized hands-on examinations of plants, and Charles’s thesis focused on poisonous plants.

Charles remained interested in botany for the rest of his life. He established friendships with other men who shared this interest, including French botanist Andre Michaux, famed for his studies of North American flora. Michaux owned property on the other side of the Ashley River where he kept a botanical garden, cultivating plants that he sent to France. Charles mentioned visiting Michaux’s garden in his diaries, and he received some plants from him, like gardenias, paw-paw, and mimosa trees. Charles experimented with growing tea and enjoyed exotic flowers such as yellow anise. Many of the plants mentioned in his diaries are still here today.

Since we’re walking toward the river, let’s discuss the importance of the Ashley. The commercial significance of the Ashley River for Drayton Hall and other plantations cannot be overstated, but the Drayton family and their guests preferred to travel by horse or carriage, because land travel was actually the fastest way to get to Charleston. There were several ferries along the river that assisted with the journey.

Nevertheless, there were many Drayton-owned boats that traveled the Ashley River regularly. In his diaries, Charles mentioned at least five boats of varying sizes, and the names of twelve enslaved boatmen are found in primary documents. Their knowledge of Lowcountry waterways and skill at sailing and maintaining different types of boats made these men crucial to Charles’s plantation business.

Not surprisingly, the boatmen and the boats they worked on appear hundreds of times in Charles’s records. Two enslaved men in particular, Patroon Jack and Captain Tim, worked in a supervisory capacity. The title patroon, and Charles’s writings about him, tell us that Jack served in a role similar to that of a foreman. He was one of the people Charles wrote about the most in his records. In fact, many of the most-frequently mentioned enslaved people in Charles’s diaries were men who worked in similar supervisory roles.

The boatmen’s working songs, led by the patroon, were likely a familiar sound to people on this landscape in the 18th and 19th centuries. Boatmen’s work occurred day and night, year ‘round. Tides, wind, and the unpredictability of Lowcountry waters often hindered their work. Charles described numerous occasions when work was delayed or people were unable to travel because of tides or weather.

These factors made the boatmen’s jobs difficult and frequently dangerous. Charles recorded multiple accidents involving boats. One night in February 1799, two enslaved men, Joe and Toby, were knocked overboard when working on one of the boats. Charles wrote: “Joe and Toby were knocked overboard by the sloop’s boom last night. Poor Joe could swim, and he was drowned – Toby could not, and saved by catching hold of the canoe. Neither skill nor wisdom can avail destiny!”

The primary function of the boats was to transport crops, produce, goods, and enslaved laborers from one plantation to another and to the markets of Charleston. The sloop could convey at least 89 barrels of rice and may have been capable of carrying over 20 tons of cargo.

PART FIVE: ASHLEY RIVER PROSPECT (19:44)

You’re approaching a modern columbarium for the contemporary Drayton family. It’s located close to the edge of the walk, just beside the river. The Draytons who lived here historically were interred in various church graveyards, such as nearby Old St. Andrew’s Parish; however, an African American Cemetery, which you’ll pass as you exit the property, has been in use since the 18th century. You’re welcome to visit the cemetery.

When you’re ready, turn so the Ashley River is on your right, and we’ll walk beside the river to our next stop. Pause when you reach the benches at the main allee in the center of the lawn. There are some things there I’ll point out to you.

As you’re looking around this area, you’re seeing some historic trees, but most of these plants are less than 100 years old. You’ll probably also see or hear many types of birds and other wildlife. The property is home to squirrels, armadillos, deer, feral pigs, and many other animals. There are important habitats here for migratory birds, and since the Ashley is a tidal river, you may see dolphins.

PART SIX: MAIN ALLEE (20:50)

You’re now nearing the benches at the main allee—the tree-lined path that looks toward the main house. If you haven’t, pause the tour until you get there.

As you look toward the main house, you might notice that the ha-ha is completely invisible, serving its purpose without disrupting your view.

Now, turn and face the river. Have a seat on the benches if you need to take a break while I tell you about this area. The benches are located on a bump-out into the water. This artificial feature, and a good deal of Drayton Hall’s shoreline, was secured by the US Army Corps of Engineers in a revetment project in the mid-1990s to control erosion.

Looking across the river, you’ll notice undeveloped wetlands on the other side. In the 1750s, some of the land you’re looking at was advertised for sale with a very specific selling point: “From this house you have the agreeable prospect of the Honourable John Drayton, Esqr’s Palace and Gardens.” John Drayton purchased the property and sold it again a few years later.

In the late 20th century, plans emerged to develop the higher ground on that side of the Ashley. Drayton Hall and the National Trust for Historic Preservation wanted to preserve the land and protect Drayton Hall’s historic view shed and environment. Fortunately, through membership contributions, we were able to permanently protect the land by purchasing it. The land will remain undeveloped, and an easement is held by the Lowcountry Land Trust.

In October 2021, through collaboration with other conservation and preservation organizations, Drayton Hall Preservation Trust acquired another significant undeveloped piece of property in the Ashley River Historic District. The Oaks plantation site, just a few miles upriver, which features a freshwater maritime forest and saltwater wetlands, will also remain conserved and undeveloped. Your support enables us to preserve and protect Drayton Hall and these other important historic and natural resources.

As you take in this area, consider the amount of expertise, skill, and labor necessary to develop and maintain this landscape. Some of the enslaved men who performed tasks related to the gardens and landscape were July, Emanuel, Exeter, Hercules, Prince, and Toby Cook. Charles recorded purchasing tools for some of them, as well as three women named Diana, Sess, and Sue, whose primary work may have been related to agriculture.

Charles sent some of those individuals to work at other plantations on occasion. For example, when Exeter learned how to mow with a particular type of scythe, Charles had him travel to a nearby property, called Savannah, to mow hay with Emanuel and Toby. The three men worked together somewhat regularly. On one occasion, Exeter and Toby brought Emanuel to Charles for medical attention after he was bitten on the ankle by a spider. Though he experienced pain and other symptoms, Emanuel survived the ordeal.

Now, let’s continue walking in the same direction with the river on your right.

Charles Drayton’s diaries reveal that his plantations utilized a task system of labor in which enslaved individuals or groups were assigned a task to complete within a specified timeframe. One example involving the gardeners was recorded in November 1793 when they were assigned to dig a double-sloped ditch—possibly a ha-ha. The daily task was 16 feet. The ditch was finished in December.

Charles repeatedly referred to enslaved people as “taskables” in his writings. Once their task was completed, individuals returned to their homes to tend their own gardens, perform housework, mend clothing, and take care of their families. The enslaved community at Drayton Hall was constantly monitored by men such as the white overseer and enslaved driver, and a watchman kept guard at night to ensure no one was outdoors after bedtime. This was recorded in an undated documented entitled “Plantation Rules.”

Another white man who served in a supervisory role was a gardener named J. McLeod, who lived at Drayton Hall with his wife for at least five years in the 1780s and ‘90s. McLeod performed and directed agricultural tasks, sowing and harvesting corn and potatoes alongside enslaved laborers. Like other white employees at Drayton Hall, he held authority over enslaved people working on the landscape. In 1794, Charles recorded an incident when Emanuel, Exeter, Toby, and Prince left Drayton Hall because of what Charles called “McLeod’s threats.” He did not record what McLeod had said to them. When July died, Charles held McLeod partially responsible because McLeod had sent July to fetch wood while it was raining, which Charles believed had contributed to July’s illness.

Now, we’re approaching the site of another building I want to tell you about.

PART SEVEN: GARDEN HOUSE (26:14)

Around 1747, John Drayton had a Garden House constructed near the bank of the Ashley River. Have a look at the site of the building while I describe its uses.

Based on a drawing by Charles Drayton’s grandson Lewis Reeve Gibbes, the Garden House was a brick building with large windows facing Drayton Hall. You can see it in image G of your map. The rounded bricks that you see in the ruins of the building were ornamental. These embellished bricks were rubbed to create their rounded shape, and the Garden House itself was constructed on an artificial terrace, which allowed for impressive views. The ornamental façade facing the main house featured an inscription with the date 1747, and its site on the landscape made it visible from the main house.

The Garden House likely functioned as a social space originally, and Lewis Reeve Gibbes referred to it as a conservatory in his sketchbook. As the Draytons and their guests enjoyed a turn, or walk, through the garden, they might stop here for conversation, Enslaved house workers such as Fanny and Judith may have prepared refreshments for them, bringing stemware and wine bottles from the main house. Archaeology reveals such objects were used in the Garden House. Sometime after the 1840s, the building was destroyed by fire.

As you stand in front of the site of the Garden House, facing the river, turn to your left and you’ll see a canal. Walk toward the canal until you’re standing beside the palmetto trees next to the Garden House site.

This canal was part of the elaborate ditch system I mentioned earlier. The plantation’s historic commercial area was on the other side of the canal. Before rice and other commodities from Drayton plantations were taken to market, they were shipped to Drayton Hall to be weighed, packaged, counted, and processed.

There was a wharf located between Drayton Hall and Magnolia Plantation, farther up the river. There were storage buildings close to the wharf where much of the work I just described took place. George, who Charles described as the butler in the main house, often gathered information about incoming and outgoing shipments for Charles’s record-keeping.

One night in 1794, a storage building near the Drayton Hall landing was burned. Charles wrote: “It does not appear to have been other ways done than by design.” He believed an enslaved man named Timee had started the fire. This is only one dramatic example of possible resistance to enslavement Charles recorded in his diaries.

When you’re ready to continue your walk, turn so your back is to the river and the canal is on your right. Begin walking, following the path that leads between the canal and the large azalea bushes. This path will lead you into a smaller garden space surrounded by bushes with a single camellia planted in the center.

This camellia was planted by Richmond Bowens, Jr. in the 20th century. His paternal grandparents were Caesar and Ellen Bowens. Mr. Bowens was born and raised at Drayton Hall, and his family resided in the Caretaker’s House, which I’ll point out to you in a few minutes. During his lifetime, he recorded oral histories and shared his knowledge of the post-Civil War communities at Drayton Hall. His recollections are invaluable to our understanding of life here in the 20th century.

When you’re ready to proceed, exit this small space and immediately turn right. You’ll see a bridge going over the ha-ha we saw earlier. Walk over the bridge when you reach it. Please avoid any bridges that are roped off.

PART EIGHT: HISTORIC LAWN AND GARDENS (30:12)

Unlike the front lawn, the back lawn and garden at Drayton Hall have seen many changes over the years. The gardens located here during John Drayton’s ownership may have included a woodland feature with meandering paths.

Now, after you’ve walked over the bridge, pause for a few moments so I can tell you a bit more about the landscape you’re viewing.

In an undated inventory, Charles Drayton recorded a list of books on many topics, with several related to gardening, garden design, or water features. Some of the notable titles he listed include Phillip Miller’s Gardener’s Dictionary and Gardener’s Calendar, Richard Bradley’s New Improvements of Planting and Gardening, and Stephen Switzer’s An Introduction to a General System of Hydrostaticks and Hydraulicks, Philosophical and Practical. These books, and many others in the inventory, were published in the early- to mid-1700s. We don’t know for certain, but some of them may have belonged to John.

Archaeology will tell us more about John and Charles Drayton’s gardens. Not all archaeological research requires digging; ground penetrating radar, or GPR, is used to gather data about different depths underground, while Light Detection and Ranging, or Lidar, is used to examine the ground surface. Archaeologists can use GPR and Lidar to detect features such as foundations and soil disturbances as well as artifacts.

Some landscape features constructed during Charles’s period of ownership still exist, such as the ha-ha we’ve seen. Over time, the garden had walking paths, ornamental statues and fountains, and a bowling green, which July was responsible for mowing. The bowling green was a social space where the Draytons and their guests played games like lawn bowls, a popular English game similar to bocce ball. There was a kitchen garden, and primary documents reference over 30 outbuildings, including a barn, stable, dovecote, and storage buildings. Perhaps archaeology will reveal the location of some of these features.

Let me direct you now to our next focal point: the privy. It’s a small brick building between the main house and the Visitors Center complex. From where you are, with your back to the ha-ha, the privy is partially behind the trees in front of you. While you’re walking, I’ll tell you about an accident that occurred during the construction of a barn at Drayton Hall.

In his diaries, Charles described the construction and maintenance of some buildings on the plantation. Many of those diary entries contained references to enslaved carpenters, who were often led by a foreman named Quash. In October 1804, the carpenters were erecting a barn when one of them, Toby Carpenter, fell from up high and, according to Charles, was “greatly crippled and bruised so as to be incapable to walk.” A couple of weeks later, Charles said Toby “hobbled” to the barn and began to work again. Less than a month after the accident, Charles wrote a final entry about it: “Toby ascended to shingle the barn roof.”

When you reach the privy, the small brick building, feel free to step inside. And if you’re unfamiliar with the word “privy,” perhaps you’ve heard the terms “necessary” or “outhouse.”

PART NINE: PRIVY (33:32)

The 18th-century privy was likely constructed by enslaved bricklayers. Carolina, the foreman of a group of bricklayers, was another enslaved man Charles Drayton wrote about the most in documents. Carolina attempted to achieve his freedom on multiple occasions, but either returned on his own or was captured, jailed, and brought back each time. He may have led the construction of this building. As you look inside, you’ll see a drawing of what the interior looked like in the 1840s.

This privy had seven seats and may have had social uses for the Draytons. That might surprise you, but consider that the social concepts of privacy and personal space that we have in the 21st century really didn’t exist in the 1700s. And keep in mind that there were also chamber pots used inside the main house. Archaeological evidence suggests that enslaved house workers emptied chamber pots here in the privy. In fact, a few mostly-intact chamber pots were recovered here by archaeologists.

When you exit the privy, turn to your right and round the corner to stop under the window. Look down at the ground where the wall of the privy meets the earth and look for an arch in the bricks. As I mentioned earlier, a series of ditches was constructed around the property, and they were linked to the Ashley River. A partially subterranean drainage system was built to flush out the privy. You can see a picture of it taken during an excavation in Image K.

When you’re ready to continue, begin walking back toward the Visitors Center and I’ll tell you about the phosphate mining period here. You’ll walk through the open gate to enter the Lenhardt Garden.

PART TEN: LENHARDT GARDEN AND CARETAKER’S HOUSE (35:30)

The Draytons’ use of Drayton Hall diminished over the 19th century, but enslaved residents remained on the plantation and continued to perform agricultural labor. By the Civil War, the Draytons had not utilized Drayton Hall as a primary residence for decades, even though there was an enslaved population living and working here. The reasons why the main house was not damaged or destroyed during the Civil War are unclear, but there are some theories you can read about in the Caretaker’s House. I’ll tell you how to get there in a minute.

After the Civil War, newly emancipated people looked for paying jobs. Some individuals who’d been enslaved at Drayton Hall left the property, while others remained nearby. Meanwhile, the Draytons sought new ways to produce income. They decided to lease Drayton Hall to a phosphate mining company.

This area is rich with phosphate, a marine mineral deposit used in commercial fertilizer. The phosphate industry became a substantial source of income for many landowners in the Charleston vicinity in the decades following the Civil War.

The mining company that leased Drayton Hall hired many Black laborers and leased some incarcerated African American men from the state. At the beginning of the Jim Crow era, laws called Black Codes were enacted to limit the freedoms of African Americans. Accused violators were frequently sentenced to hard labor in state prisons or were rented out to private citizens or companies where they were often treated as they had been when enslaved. This practice continued throughout the south well into the 20th century.

During the phosphate mining period at Drayton Hall, a railway was constructed on the property to easily transport phosphate from place to place. Many buildings were constructed too, including storage and processing facilities, a company store, and additional housing. The Caretaker’s House is the only one of the those structures still standing today. During the same period, modifications were made to the privy, and it became used as an office.

The phosphate laborers lived on the property, utilized the company store, and formed a community that survived through the Jim Crow era. In the Caretaker’s House, the red wooden house inside the Visitor Center courtyard, you’ll learn more about that community, where buildings were located, and how people lived on the property in the 20th century. I encourage you to visit the Caretaker’s House when you finish this tour. A brick path will lead you there from the Lenhardt Garden.

In 2018, the Sally Reahard Visitors Center and Lenhardt Garden opened at Drayton Hall. The Lenhardt Garden features native and imported plants, including some that Charles Drayton wrote about in his diaries, like camellias, foxgloves and Stokes’ aster. Seasonally, we enjoy the lovely light pink blossoms of Champneys Pink Cluster Rose, believed to be the first noisette rose, which originated in Charleston. John Champneys was an acquaintance of Charles Drayton, and Charles visited his garden on occasion.

The Live Oak, underplanted with garden ferns, in the center of this garden was likely planted during Charles’s ownership of Drayton Hall in the early 1800s. The allees on opposite sides of the garden are created by white crape myrtle standards. The quadrants, lined with Japanese boxwood, contain beds of some perennials and annuals mentioned in Charles Drayton’s diaries.

In some of his reference notes, Charles Drayton wrote: “there are many sources of pleasure in landscape gardening,” and “places are not laid out with a view to their appearance in a picture… but to their use, and the enjoyment of them in real life.” That, Charles felt, constitutes a landscape’s true value.

Thanks for visiting Drayton Hall. Your support is vital to the continued preservation and research of his property, and we’re pleased that you chose to take a walk around the landscape.

Enjoy the rest of your visit.