Drayton Hall

Drayton Hall

Drayton Hall House Tour

0:00 Introduction

· Welcome to Drayton Hall. I’m Amber Satterthwaite, Curator of Education and Museum Programs, and today I’ll lead your experience through Drayton Hall and provide information about the people who lived and worked here during the 18th and 19th centuries.

· Before you leave the visitor center area, I want to remind you that no food or drink is permitted in the main house except bottled water. Please dispose of other items in the wooden trash receptacles located in the center of the breezeway area.

· Since you’ve seen the introductory film, we can jump right in. Turn so you’re facing the main house. Begin your journey by exiting the visitor center and moving towards Drayton Hall, taking the gravel path to the right. Pause when you reach the brick circle at the end of the path, and I’ll let you know when to continue.

· John Drayton, the original owner and likely designer of Drayton Hall, died in 1779. A few years later, his oldest surviving son, Charles, purchased Drayton Hall from John’s widow, Rebecca.

· Charles and his wife Hester Middleton moved in with their children in 1784. But it wasn’t just the Drayton family who lived here.

· Charles Drayton was trained as a physician, but like his father, Charles was also a planter and enslaver. Not only was the Draytons’ fortune accrued from the exploitation of slave labor; the entire economy of South Carolina—where the primary cash crop in the late 18th century was rice—was dependent upon slavery, with laws in place to protect the institution. Other important commodities grown or produced by enslaved people in South Carolina during this time include indigo, cotton, and salted meat for export to the Caribbean.

· From 1784 until his death in 1820, Charles Drayton kept detailed diaries about life at Drayton Hall and numerous other plantations he owned. In those diaries, he mentioned over 190 enslaved people by name, sometimes providing details about their relationships, personalities, and jobs. Charles referred to enslaved people by their first names only, and sometimes he used occupational names, such as Quash Carpenter, to identify a person based on their job.

· The 190 people Charles mentioned did not all live at Drayton Hall. The number of people living on this property fluctuated depending on where Dr. Drayton assigned workers according to growing seasons, agricultural needs, and the opportunity to lease skilled craftsmen such as blacksmiths and carpenters for hire. Those who worked in the main house likely lived in the main house. Others lived in a complex of wood frame houses which we’ll discuss in more detail later.

· One of the most prevalent themes in Charles’s diaries is movement: specifically, the movement of enslaved people across a network of plantations and the work they performed on those properties. One person who traveled constantly was Will. He is the most frequently-mentioned enslaved person in the diaries.

· When you’re ready, begin moving across the grass towards the main house. As you look at the house, you’ll notice a couple of landscape features that we’ll discuss later. For now, imagine that the circular mound in front of you is not there and the driveway you came in on today extended all the way to the front steps of the main house, which was flanked on either side by two-story brick outbuildings. You’ll see an image of this shortly.

· As you picture this scene, imagine Will riding up the drive on his horse. Will probably lived at Drayton Hall, and part of his job was to act as a messenger for Charles Drayton. But anytime he brought news to Dr. Drayton, Will also had news to share with the enslaved workers at Drayton Hall. They likely looked forward to hearing from Will, who had greater access to information than most enslaved people who lived here.

· Your tour today begins in the cellar of Drayton Hall—the busiest part of the house, and where many enslaved individuals lived. You’re welcome to take pictures or sip bottled water inside, but we ask you to assist us in preserving the building by not touching or leaning on any part of the house. There are benches throughout the house for you to use.

· Please enter the cellar through the central door with the wrought iron harp gate between the front steps. Feel free to pause the recording at any time if you need a few seconds to enter a space or ask a question. Trained interpreters and curatorial staff members are inside to welcome you and answer your questions.

5:01 Cellar (central area)

· Charles Drayton wrote about a servants’ hall, which was likely located in the cellar. He stated that an enslaved man named Quash—one of the people he wrote about the most—and a team of carpenters made “large tables for the kitchen and servants’ hall.” The servants’ hall may have served as a place for enslaved people working in the house to eat, meet, work, or wait for assignments.

· As you walk into the center of the cellar, you’ll notice a very large fireplace on the right wall. This space functioned as the kitchen. While it was common, especially in the South, to have a separate summer kitchen for the hotter months, it was not unusual to have a kitchen in the main house. There is no evidence or documentation that there was a separate kitchen building associated with this house.

· A number of enslaved people worked in the kitchen, and their work was directed by a cook, such as Dumplin. Scullery maids washed dishes, cut vegetables, scalded and plucked poultry, and descaled fish; spitboys tended fires and undertook many other food-related tasks. One cook, Toby, was responsible for butchering larger animals.

· For cooking, there was a large, iron swingarm in this fireplace. Pots and kettles hung from the swingarm. A cooking surface called a grid iron may have been set directly over the fire. Small-scale baking could take place on the floor by using special covered pots called Dutch ovens.

· Dumplin and the other cooks not only had to be very skilled at preparing food, they also needed to be detail-oriented, not to mention strong, and no fire was left unattended under their watch.

· The kitchen was an active, noisy place filled with the smells of smoke and food in various stages of preparation. When designing the house, John Drayton wanted to ensure that the noise and odors of the kitchen stayed here in the cellar. Doors and plaster ceilings muffled sounds and controlled odors.

· There were two staircases in the cellar. The first is in the back left corner, where you’ll notice a stair leading to the first floor. At the top of that staircase is a door that not only controlled access to certain areas of the home, but also acted as a shield for the work taking place in the cellar. Feel free to pause this tour and go take a look if you’d like.

· The second staircase was located closer to the center of the cellar. Stand with your back to the large fireplace. This staircase began in the passage across from you.

· The staircase was tucked behind the corner and was contained by a wall and a closing door.

· Having a door at the bottom of the staircase again helped cut down on noise and odors making their way to the first floor of the house. A termite infestation in the early 20th century necessitated the removal of the first flight of these stairs, but if you look at the plaster walls, you’ll be able to see markings where the stairs were once located. They functioned as just one of several routes for enslaved workers to move through the house as they completed their daily work. You’ll get a good view of this staircase in the Dining Room on the next floor.

· Now, move towards the back of the cellar and we’ll explore some other uses of this space.

· As you near the back door, you’ll get a glimpse of the landscape and the Ashley River. While the Draytons and their guests typically did not travel by boat, the Ashley River was a busy thoroughfare for boats carrying supplies and enslaved people to and from Charleston and from one plantation to another. The enslaved men who worked on boats owned by Charles Drayton were supervised by a man Charles called Patroon Jack. Patroon is a title for an enslaved boat captain.

· Turn so your back is to the river. If you look into the room on your right, you’ll see that an archaeological excavation recently took place. This room is unlike the others because it doesn’t have a tile or stone floor—only dirt. The room regularly has a higher level of moisture than the others, and archaeologists wanted to identify the source of the moisture, the historic uses of the room, and whether there was evidence of historic tile, brick, or stone flooring.

· The excavation revealed that there had been a brick or tile floor in the room historically, and a trench, pre-dating Drayton Hall, is a likely source of moisture issues in the space today.

· Investigations also identified evidence of human occupation on the site hundreds of years before the first European colonist ever arrived in South Carolina. Now, let’s move to the room directly across from this one and walk inside.

10:19 Brick Floor Room

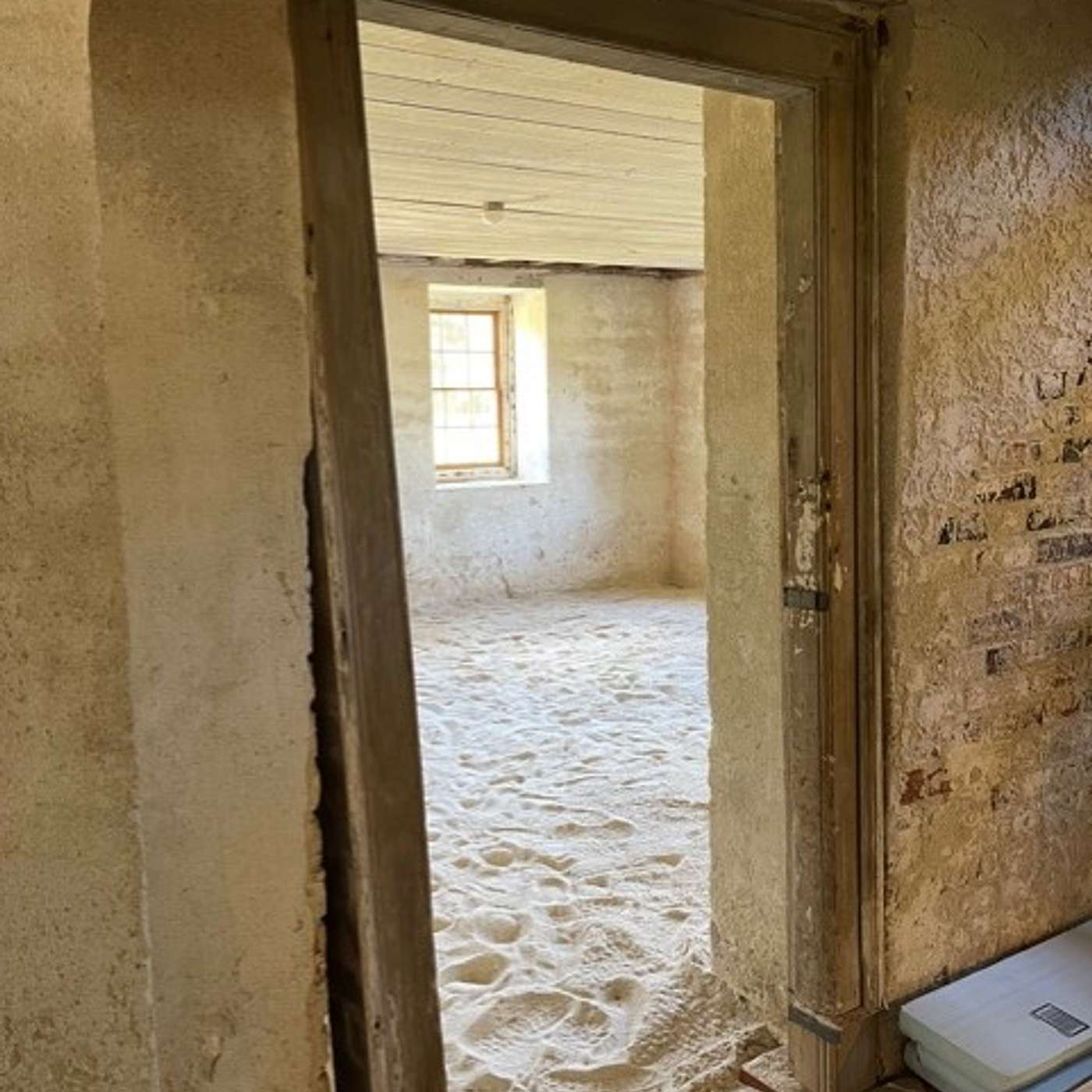

· This room, like the one you just saw, does not contain a fireplace. Nevertheless, both rooms likely served dual purposes as storage areas and living spaces for enslaved workers.

· There are no records of who lived in which room, but we know people lived in this room at some point because there is evidence on the door jamb of a makeshift lock being created and used from inside.

· Exactly what type of furnishings were used in these rooms is unknown, but multiple people likely shared each space.

· The only glimpses we get of enslaved people’s personal lives are through the stories Charles Drayton felt were worthy of recording in his diaries. On occasion, Charles wrote about important events in their lives, but we only see those details through his eyes, because enslaved people did not leave written records of their own: it was illegal in South Carolina for them to learn to read and write.

· One fascinating story about Dumplin sheds light on funeral customs within the enslaved community at Drayton Hall, but it also raises many questions for us as researchers.

· Dumplin, who worked as Charles Drayton’s cook, was an integral part of this community. Charles wrote about Dumplin observing a West African funerary tradition of sitting up all night with the body of an enslaved man named Jack Groom following his death. Charles recorded it in his diaries because Dumplin became sick and died soon after. He wrote: “Dumplin the cook, returning home after sitting up late with the corpse in a draught of cold air, was seized with a congestion in the head, which terminated in Palsy of the right side.”

· Some of the questions we have are: where was Dumplin coming from? Was there a relationship between her and Jack Groom? Where did Jack live, and where was his body when Dumplin returned home? We may never have the answers to those questions.

· Now, when you’re ready, head back out into the main room and immediately turn left and walk into the passage.

12: 28 Passages

· The passages off the main room of the cellar housed additional storage spaces with decorative shelving. Exterior doors in both passages provided many ways for people to enter and exit.

· Despite their status as pathways and storage spaces used by enslaved laborers, these passages received some interesting architectural treatment, including red paint on some details and scalloping on the shelving.

· Some of these shelves were covered with locking doors. It’s possible that George, the butler, managed the keys or otherwise controlled access to the locked spaces, since Charles Drayton mentioned giving George keys to other storage areas on the property.

· The society that everyone at Drayton Hall lived in in the 18th and early 19th centuries was highly stratified, and a person’s life and opportunities were, in many ways, determined by their social status. At the top of the hierarchy was the gentry class, to which the Draytons belonged. There were middling and lower classes, and enslaved people were at the bottom of the social ladder.

· In a gentry household, the butler was generally the highest-ranking person on staff and often had access to certain locked areas. Even though George was enslaved, he was still at the top of a social hierarchy that existed within the enslaved population working in Drayton Hall.

· When you’re ready, walk back into the main room and towards the front of the cellar.

14:12 Room with Door

· As you approach the front of the cellar, enter the room on your right. The free-standing door displayed here is the door that originally separated the room from the main area of the cellar. Every room in the cellar had doors like this one. It’s significant because it shows us once again that even here, John Drayton was very aware of formality: the side of the door that faced the large, open room you just came from has raised panels and was painted from the time it was installed. But the side of the door that faced into this space used by enslaved workers was not nicely finished. That side was never painted, and the door was used for a very long time before whitewash was applied to it.

· Just like the rooms you saw in the back of the cellar, the two front rooms functioned as both storage and living spaces. Unlike the other two rooms, the front rooms have fireplaces, and paint analysis has revealed that cooking took place in both chambers. Also, both of the front rooms have exterior doors, so the rooms may have been pass-throughs for other workers attending to their daily tasks, meaning there was little privacy for anyone living in the cellar.

· One of the people who may have spent time in this space was Billy, who Charles referred to as his waiting boy. Billy was one of several people who was highly visible on the main floors of the house and here in the cellar. He had some skill as a tailor, so he may have helped care for Charles Drayton’s clothing, work which could be done in the servants’ hall or under the supervision of a laundress, such as Beck.

· When you’re ready, exit this room and head back out the front door of the cellar.

· As you leave the cellar, you’ll notice some sections of columns on the floor. Those are pieces of the original columns from the lower portico. They were replaced under Charles Drayton’s direction in the early 1800s, and they have been stored in the cellar since at least 1875. Charles wrote that it took 27 men to take down one column.

· Once you’re back outside, walk towards the mound in front of you, then turn back to look at the front of Drayton Hall so we can discuss the architecture of the building. Pause the recording if you need to.

16:44 Mound

· After purchasing this property in 1738, John Drayton had a home built that fit the lifestyle he wanted to live and the image he wanted to project. Drayton Hall wasn’t a plantation for producing cash crops—it was his home, and the headquarters of a vast plantation empire totaling over 76,000 acres of land.

· While we have very few written records from John, we believe he visited Europe as a young man—perhaps he was educated there. He may have seen grand villas designed by Italian renaissance architect Andrea Palladio.

· We believe he was drawn to Palladian architecture and collected books on the subject for his library. Eventually, he designed this home utilizing Palladian design principles.

· Palladianism allowed John to display his wealth and intellect as well as his power over other people. A villa like this is a beautiful place that exists to create and maintain wealth and power, and that was accomplished by the dominance of some people over others. Not just a home, this Palladian villa embodies John’s investment in the concepts of order and hierarchy—ideologies that prevailed in the world in which he lived.

· Palladio, and likewise John Drayton, utilized architecture to compartmentalize people based on their social status and controlled how they entered the home, how they moved through it, or whether they even entered at all.

· The control exerted over people who entered the house was constant, but its nature was dependent upon a person’s social status. While white gentry guests followed a formal social path through the home, which was determined by the formality of architecture in each space, enslaved people did not move through the rooms based on architectural orders. They were controlled in a much more direct way.

· When you’re ready, let’s head up onto the portico and pause for a moment. There are a few more things I want to share before we head inside.

19:05 Portico

· Drayton Hall was constructed by teams of enslaved, free, and white craftspeople. The wood used in construction was local, and the bricks were made onsite, but John Drayton ordered expensive building materials from Europe, including stone columns, stone tiles, marble, and very large windows, with panes the same size and shape as what you see today.

· One of the most unique features of Drayton Hall is this front portico. When he designed the house and landscape, John Drayton intended for this to be the front of his home. In fact, he intended for his family and guests to always arrive at Drayton Hall from the road, rather than from the Ashley River, which is behind the house. The road to the house that you drove in on extended all the way to the portico, so this was very much the focal point. This portico is unlike any other in the world because of three things: it recedes into the structure, it projects out of the main structure, and it’s two stories tall with stacked columns.

· The earliest known image of Drayton Hall is on an easel for you to see here. This copy has been blown up; the original painting is much smaller. Here, you can see several things that are no longer standing today.

· The purposes of the two flanker buildings are unknown, but they may have served as work or living spaces for family, guests, or perhaps some enslaved workers. By around 1900, the Drayton family decided to take the flankers down, perhaps because they were in poor condition.

· The flankers were originally attached to the main house with a colonnade, as you can see in the image. You might also notice that on either side of the house complex is a large, tall fence or palisade. Not only does this all look imposing and powerful, but it controlled what people saw when they arrived on the property. John Drayton didn’t want people to be able to see the private areas in the back of the house. Only certain guests were invited to experience the formal gardens that were located there. Remember, the entire design was meant to create order and control.

· Take a look out on the landscape. Aside from the drive being different, there are a few other modifications from the 19th and early 20th centuries. The tiered mound in front of the house was built in the late 1800s as a decorative feature.

· The woods on either side of the road that are thick today were cleared fields in the 18th century, and a complex of houses, which is no longer standing, was visible and could be monitored from this spot.

· In the cellar, you saw the homes of several people. There were many other enslaved people who lived at Drayton Hall, but they lived in a separate complex. A map, which appears to have been drawn by Charles Drayton, indicates that their homes were located close to the African American Cemetery.

· That complex consisted of ten wood frame houses that were built side-by-side. In 1804, Charles wrote that the houses, which he called tenements, were being “walled and roofed, though not divided,” so they may have been divided into two rooms later. Every house in the complex had a garden plot associated with it. There was also a separate home designated as the Driver’s house.

· On Charles Drayton’s plantations, he named one enslaved man the Driver. Drivers had many responsibilities: they assigned daily tasks, ensured work was completed on time, and assisted a paid white overseer with administering punishments. Drivers reported directly to Charles Drayton and did so on a regular basis.

· The area I just described was probably visible from this portico. Those houses were not preserved like other buildings on the property, but we hope future archaeology will reveal more information about how people lived within that complex.

· Archaeology plays a crucial role in our understanding of how people lived here—especially people who did not or could not leave behind written records.

· Before we go inside, I want to briefly introduce you to our preservation philosophy. Drayton Hall was owned by a single family for seven generations. The house was never wired for electricity, and plumbing was never added.

· When the Drayton family sold the house and property to the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1974, the decision was made to conserve the building instead of restoring it to reflect a particular time period. Today, the property is still owned by the National Trust, and the Drayton Hall Preservation Trust is responsible for stewardship of the house, its surrounding landscape, and its diverse collections.

· Walk inside when you’re ready. Remember, if you have a question, feel free to pause the recording and take time to talk with a staff member. You’re welcome to sit on the benches inside, but please do not sit on the window seats, and be careful when going through doorways.

24:24 Main Floor

· Here in the Great Hall, you’ll see some examples of how our preservation philosophy works. Look up at the ceiling. This is the third ceiling in this space. We’ve preserved the ceiling by reuniting sections of plaster that were separated over time using a special epoxy. This technique does not make the ceiling look pristine as it did when first installed, but it does help save the original material so we can continue to appreciate it and study it in the future.

· We’ve taken a similar approach with paint on the walls. You can clearly see paint loss on the walls throughout the house. The wood grain is not supposed to show through. When the paint was applied it looked just as you would expect a new coat of paint to look—an even, solid color across the entire surface. But, the last time this room was painted was 150 years ago.

· Instead of repainting, we’ve borrowed a technique from the fine art conservation world: we’ve applied a special invisible solution to the painted surfaces that helps re-adhere the paint to the wall. You can help us preserve Drayton Hall by being careful not to touch or come into contact with these painted surfaces.

· Historically, this room, like so many in the house, was a multi-functional space. It could serve as a place to greet guests—especially gentry-class ladies and gentlemen. That may have been part of George’s responsibilities. George, who I mentioned in the cellar, worked as Charles Drayton’s butler. In a gentry household, the butler had a very important job. He managed schedules, supervised other workers, and was highly visible to guests.

· In his diaries, Charles Drayton made it clear that he sought and trusted George’s opinion on matters as simple as counting supplies or as delicate and complicated as determining the future of another enslaved individual.

· Billy, a young man who also lived here in the main house, had run away after Charles accused him of stealing. As a waiting boy, Billy worked very closely with both Charles and George. When he returned after running away, Billy asked Charles if he could hire himself out—if he could live in Charleston and work odd jobs. He promised to pay for his own lodging and clothing, and he said he would play Charles $300 per year.

· Charles wasn’t sure it was a good idea, and he discussed the matter with George, who was concerned that Billy might leave again. Charles wrote, “George thinks, as I do, that he would make an excellent driver.” And soon after, Billy was indeed sent to work on another of Charles’s plantations as a driver—a supervisory position that came with a great deal of responsibility.

· Charles’s diaries present a significant yet complex relationship between him and George, all from Charles’s point of view. When George died, Charles wrote about the loss, calling George “a long-timed deputy” and saying that his death created “a blank in our routines in life, not soon filled up.”

· When George’s daughter Fanny died a couple of weeks later, Charles wrote, “She too leaves a blank,” indicating that Fanny may also have had a very visible role in the main house.

· Now, turn so your back is to the fireplace. You’ll be facing a wall with two doors. Go into the door on the right.

28: 17 Dining Room

· Charles Drayton identified this as the Dining Room, a formal space for meals with family and guests.

· In the cellar, we observed a missing staircase that provided one way of passage for people moving through the building. Here, in the corner next to the fireplace, you have a good view of what this stair looks like. Note the lack of a handrail and lighting. You’ll also probably notice how narrow, steep, and uneven the stairs are.

· The door to this stair was generally kept closed so enslaved people using the stairs were neither seen nor heard by the Draytons and their guests.

· Throughout the day, people were carrying laundry up and down the stairs. Chamberpots from the Draytons’ bedchambers on the second floor had to be carried out and emptied. And food was brought up from the cellar by way of this stair.

· Perhaps Fanny was one of the women who brought heavy trays of food from the kitchen up to the dining room.

· This was the only staircase in the house that went from the cellar all the way up to the attic—it’s still the only way to access the attic. The attic was a storage space, but it’s unlikely anyone lived there.

· Another interesting feature in this room that might draw your attention is what appears to be a bricked-in doorway on the other end of the room. In fact, there was never a functioning door here. This is called a sham door. The brick that you see is part of a load-bearing interior brick wall. In the 18th century, it was covered by a fake door. Its only purpose was to maintain symmetry in the room. There’s a door on the right, so in order to balance the room esthetically, a sham door was installed on the left. Later, some of the Draytons decided to remove the non-functional door.

· One of the things that’s really interesting about this doorway now is seeing the interior brick wall. For example, look for part of a diamond shape of bricks in the upper right section of this wall. This shape is referred to as a diaper pattern. Since the wall was never meant to be seen—it was always covered by the sham door and the wooden wall panels—we’re not sure why this decorative pattern is here. Perhaps a mason was practicing the technique.

· The bricks used to construct this building were likely made onsite by enslaved children and adults, and some of the bricks bear their fingerprints. One set of fingerprints is visible in the brick just above the lowest corner of the diamond.

· Now, use the door to the right of the fireplace to move into the next room. You’ll pass through a small hall-like space. There’s shelving here, perhaps for dishes or linens, and it functioned as a workspace for individuals like Fanny who were doing jobs here on the first floor.

31:21 Library

· Charles referred to this room as his library. A library could house a collection of books, which Charles certainly had, but the term could also be used to describe a gentleman’s office.

· The books in Charles’s collection, which were stored in furniture rather than on shelves, included architecture books that his father had probably used when designing Drayton Hall.

· The wide array of topics represented in his library demonstrated Charles’s education, his ability to purchase books, and the leisure time he enjoyed to pursue reading and other hobbies.

· When you’re ready, we’ll walk directly across the Great Hall and pause in the room across from this one.

32:18 Growth Chart Room

· While the historic purposes of this room were not recorded, most of the spaces in the house likely had very flexible uses in the eighteenth century. You may have noticed both the library and this room have exterior doors that allow people to enter directly from the portico without having to go through the more formal Great Hall. Remember when I mentioned how John Drayton’s plan for the house dictated which people had access to certain spaces? This is an example, typical of Palladianism, providing direct access to a less formal room that would further allow John Drayton to maintain that control.

· In the late 1800s, the Drayton family began keeping track of their children’s growth by creating a family growth chart. You can see it on the right side of the exterior door, and if you look closely, you’ll notice that it was used through the 20th century. In fact, some of the Drayton family members still use it today.

· On the left side of the door are some other measurements. That’s where Charlotta Drayton measured her pet dogs in the early 20th century. Charlotta was interested in historic preservation and wanted those concepts applied at Drayton Hall.

· When Charlotta owned the house, she sometimes used this room as an informal dining room. Her nephew, Charlie, recalled eating bologna sandwiches and having afternoon tea in this room in the 20th century.

· Now, we’ll move through the passageway on the right side of the fireplace to access the next room. Keep in mind that these small passageways, though not architecturally outstanding, were important parts of the house where many of the activities necessary to perpetuate the Draytons’ lifestyle in the 18th and 19th centuries were taking place.

34: 23 Drawing Room

· As you look around this room, you might notice it has more architectural details than the previous one. In fact, this is one of the more formal rooms in the home, architecturally speaking, making it ideal for gentry entertaining.

· The ceiling in this room is a hand-carved plaster ceiling and is one of the only original ceilings surviving in the house. The other is under the main staircase, which you’ll see in a few minutes. This ceiling is the oldest of its kind in North America.

· You’ll notice there was another sham door in here that the Drayton family removed later.

· This room, the drawing room, was a place for formal daily entertaining—kind of like the modern-day living room, but perhaps more flexible in its uses. This was a room where Mr. and Mrs. Drayton entertained guests with refreshments and conversation. Imagine an enslaved woman such as Peggie serving tea to the Draytons and their guests here.

· And imagine the conversations that must have taken place in this room. During the Revolutionary period, the stakes were high for powerful, politically-active landowners like the Draytons.

· John Drayton’s oldest son, William Henry, a patriot, was very influential as an orator and politician during the Revolution, and he was a member of the Second Continental Congress.

· While Mr. Drayton and other gentlemen spoke of personal freedom and the nation’s independence from Britain, their wives listened on, knowing that many of those new freedoms may not apply to them.

· Meanwhile, enslaved people working in the house listened intently but wondered if the outcome of the war would have any impact on their condition.

· William Henry Drayton was a signer of the Articles of Confederation, the nation’s first Constitution-type document. The Articles left all decisions regarding slavery in the hands of the individual states, and in South Carolina, where the economy was completely reliant on slave labor, many laws were already in place to control the lives of people enslaved here.

· Charles Drayton’s diaries reveal that many enslaved individuals at Drayton Hall desired freedom and power over their lives. He often recorded over the years that despite the dangers, people who he enslaved ran away, sometimes taking family members or children with them, and there are many other references to resistance attempts in the diaries. From standing up to overseers to destroying barns where harvested crops were held, or even flooding rice fields, many people were willing to take risks and openly oppose their condition and attempt to change their lives.

· While the Draytons did not live on this property full-time after the mid-19th century, there was an African American community at Drayton Hall until 1960.

· After the Civil War, the Drayton family leased the property to a series of phosphate mining companies, which employed a number of African Americans and also leased some African American convicts from the state to work as laborers in the mines.

· In the meantime, a house was built next to Drayton Hall to serve as a home for a full-time caretaker. That home was occupied by several African American families over time and is still standing today inside the Visitor Center complex. It now houses an exhibit about what happened at Drayton Hall and how people lived on the property following the Civil War and well into the 20th century.

· Now, we’ll move to the Stair Hall. When you exit this room and head back into the Great Hall, you’ll immediately turn right and walk through the open double doors.

38:34 Stair Hall

· Here in the Stair Hall, John Drayton’s ability to afford the best building materials is demonstrated again. The staircase is made of mahogany, a very expensive wood. Mahogany is workable and ideal for intricate carvings if one could afford it.

· When selecting finishes for the home, John was married to his third wife, Margaret Glen, a native of Scotland. One of them may have been fond of the color red. Upholstery on the furniture they purchased for the home was red, and this beautiful mahogany stair was accented with a bright red, vermillion-based paint, another expensive selection. Some of the paint is still visible today where a couple of the mahogany brackets on the side of the stair have been removed. You can see that if you stand with your back to the back door and look up to your right.

· The remarkable red staircase led guests to a formal room on the second floor that functioned as a ballroom and formal entertaining space.

· One of the jobs enslaved house workers had was to move furniture as necessary based on how the Draytons wished to use a room, so any room could be used for practically any purpose.

· The layout of the second floor is nearly identical to the first floor, with some of the rooms functioning as bedchambers. There is no documentation regarding who used which room.

· There’s a secondary staircase in this room as well, but it’s tucked away in what looks like a closet. If your back is to the back door, it’s the closet on your right. You probably remember seeing this staircase when you were in the cellar earlier. It enters here, situated below the main stair.

· Enslaved workers also used the main staircase if they needed to, based on where they were headed and what task they were performing. For example, Charles Drayton wrote about a woman named Affy who cared for his children. Affy may have used the mahogany staircase regularly while escorting the Drayton children to different areas of their home.

· Affy was the most frequently mentioned enslaved woman in Charles’s diaries. She was so integral to the children’s lives that she may have even shared a bedchamber with one or more of them, and when Charles’s daughter Charlotte Drayton Manigault gave birth to her first child at her residence in Charleston, Affy traveled there and spent two weeks with her.

· On the other side of the room, you’ll notice another closet that functioned as a storage space, but also as a place for prepping dishes or other items being taken to the second or first floors. If you peek into the closet, you’ll see marks on the walls where there were once shelves and a countertop, so this was definitely a workspace. Perhaps George decanted wine here, or food being taken to the second floor may have been plated in this space before serving.

· The graffiti on the door to this workspace is mysterious and old. It looks like someone named Simon signed his name near the top of the door, but for now, his identity, and the reason why the graffiti was never painted over, is unknown.

· Your tour of the main house concludes here. When you exit the back door, you’ll be entering an outdoor space that was once the setting for formal gardens. Charles Drayton wrote about over 30 outbuildings that were located on the landscape, including a pigeon cote, barn, stable, poultry house, wood cellar, and potato house. Many, if not all, of these structures were built by enslaved carpenters like Quash and his team. Hopefully, future archaeology will allow us to find the locations of some of these buildings. Near the Ashley River, on a small terrace, you’ll see the foundations of a garden house that was used for entertaining on the private, formal 18th century landscape.

· The discoveries that enable us to share these stories with you are made possible by the Friends of Drayton Hall. If you’re interested in supporting continued research and preservation at Drayton Hall, we hope you’ll consider becoming a Friend. Please take a brochure to learn more about how your philanthropy can impact our work.

· Before you exit Drayton Hall, there is an interpreter stationed in the Great Hall to answer any questions you may have about your experience today. Please feel free to engage them in conversation—they welcome your questions.

· We hope you enjoyed your tour, and we thank you for visiting and helping us to preserve this special place and its many stories.