Firehouse Talk: Tales from the Fire Service

Firehouse Talk: Tales from the Fire Service

Firefighters Byron Temple and Creston Whitaker - Life in the Fire Service

Following their long careers as firefighters with the Dallas Fire Department, Byron Temple and Creston Whitaker join me, Mike Otto and Rett Blankenship to talk about their experiences.

Visit www.firehousetalk.com for more information

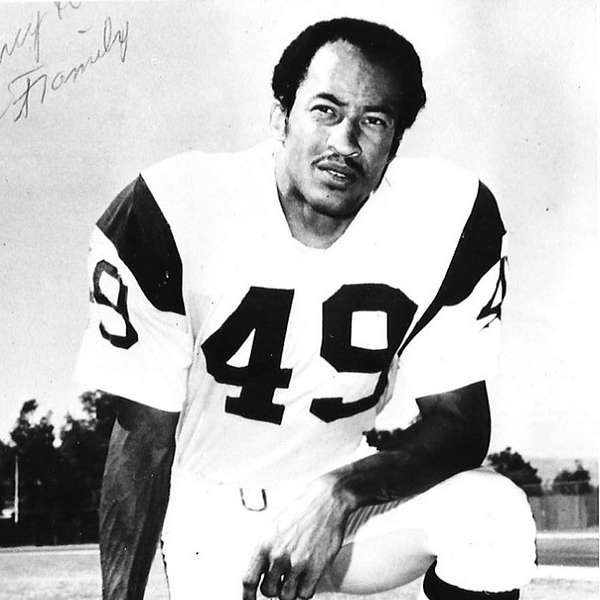

Hello everybody and welcome to Firehouse Talk. I recently invited Byron Temple and Creston Whitaker two retired Dallas firefighters to join me, my co host Mike Otto, and retired DFD. Captain Rett Blankenship for a cup of coffee down at the Dallas Firefighters Museum. While we were there, I captured a little of their personal stories on tape. We'll get to those stories in a moment. But first a little background. Both Byron and Creston joined the department in 1978. Byron was a highly respected paramedic who rode 711, one of the busiest ambulances in the city for an almost unheard of 25 years of his 37 year career, much longer than most paramedics of that era would serve in that capacity. His medical skills were exceptional, but he's probably best known for his personality and keen sense of humor. Perhaps it was that ability to keep it light and see the humor in things that allowed him to avoid the burnout that so many paramedics experience. Creston had an unusual background in that, although he didn't play college football, he did play in the NFL before joining the fire department. We'll hear a little about his years as a multi sport athlete, as well as his distinguished Fire Service career. Now on to our conversation. So Crest, what made you want to be a firefighter? How did this happen?

Creston Whitaker:Well, actually, I was trying to develop a real estate business. And I had a cousin in Illinois, who was a firefighter. And I had no experience with the department as far as knowing when the shifts, shift hours were or whatnot. I just noticed that every time that I would go to Illinois, he was off work and and I asked him, I said, Well, why are you what kind of work do you do? And he says, Well, I'm a firefighter. And so that opened my eyes initially to it, because I felt that, again, initially, I would like to have preferred profession where I could have extra time to spend on real estate or other activities. And I say initially, because I found out soon enough, when I joined that, that I had the love for the department and the off time was actually secondary.

Chuck Hampton:Were you living in Texas at the time? And is that how you came to apply with Dallas? or How did you end up choosing Dallas?

Creston Whitaker:Yes, I was in Dallas at the time. And we just to go back for family reunions, or visit different relatives, but I just couldn't help but notice he was always off work. He never was working when I got there.

Chuck Hampton:Now, before you joined the fire department, you had been an athlete in college, right? Yes. And what was your sport?

Creston Whitaker:Well, actually, I participated in two sports. I participated in basketball at University of North Texas and also in track. And, and I was honored to be inducted into their Hall of Fame for basketball and track in the middle 90s. I believe it was.

Chuck Hampton:And so after you left UNT, did you continue with sports for a period of time?

Creston Whitaker:Yes, I did. I played four years of professional football in the NFL. I know it seems strange for people that knew me and knew that I played basketball and ran track in college, but I was a little discouraged. Because in basketball, the Milwaukee Bucks had indicated that they were going to draft me and when they finally were able to attain some guy name, I think his name was Lou Alcindor. And they paid him a record about amount or what have you. And so we weren't able to come to any kind of terms. So I decided that I might consider football and a AllPro safety with the LA Rams again, by the name of Eddie metter lived in Denton at the time and he had heard that I was going to try out with the Dallas Cowboys. And so he contacted the Rams organization and George Adam was the coach at that time. And they sent a scout down. And one thing led to another and I was able to, they offered me a contract. And so I spent two years with the Rams and two years with the New Orleans Saints.

Mike Otto:Interesting.

Chuck Hampton:So after after that, you got on with the Dallas fire department that would have been what year?

Creston Whitaker:I joined the Dallas Fire Department in February of 1978.

Chuck Hampton:And then after rookie School, where did you get assigned?

Creston Whitaker:My first assignment was at three fire station. And I'll never forget coming in first day as a rookie, and I've got all my equipment on my shoulders and carrying everything I can. And no sooner than I got in the door, the bell hit. And so I was a little stunned. But Captain Wachsman was the captain and they were all going to the apparatus. I was in the apparatus room and he turned to me and he said, "Get on something".

Mike Otto:Sounds like Richard Wachsman.

Chuck Hampton:So your initial experience at the fire station was it an adventure or intimidating or what was it like it? Your first days there.

Creston Whitaker:I think initially, like most rookies, I was a little bit intimidated, just by the various challenges and things we would be faced with. It took a while to understand the mindset of many of the firefighters the agitation and things that go on. But at that particular station, which threes was extremely busy. Within three months, I think I had participated in first, second, third, fourth and fifth alarm fire in three months time at the station, and the fifth alarm fire was the at that time was the highest rated fire that you could have.

Chuck Hampton:And then paramedic school sometime within that first year or two?

Creston Whitaker:No, actually. Well, I had initially gone to paramedic school, but I had a death in the family. And so I I had to leave paramedic school and I returned probably about two years later. Which the significance of it was that our rookie class was the first class that had signed the waiver, the mandatory waiver indicating that you must go to paramedic school and you must pass paramedic school. If not then you were terminated from the department. So there was a lot of pressure on people when when they went into into paramedic school.

Chuck Hampton:A lot. So, where did you get assigned to at a paramedic school?

Creston Whitaker:My first station? I believe it was 20 No, excuse me. It was a six fire station. And again, at that time, it was it was the number one or the busiest station in the city. And I felt that it was a big challenge. And one of the unusual things that took place there was that we were at the table eating dinner one night and we looked out the dining room window and we saw the ambulance. The rescue as we call them now. Going down the street, hardwood Avenue and now all of us were sitting at the table. So somebody's stolen the ambulance And sure enough, they had, we got to the engine call the police. And after about 25, 30 minutes later, we were able to, they were able to apprehend the person that had taken it.

Chuck Hampton:So, during your time on the fire department, did you have any close calls at an incident where you felt like maybe your life was in danger?

Creston Whitaker:Yes I did, again, probably had been on the department about two years. And when I was at three station still, we got a call for a one alarm fire initially. And when we arrived, of course, we saw the smoke, we can see the flames coming out of the building and, and coming up the sidewalk was this lady saying the proverbial somebody is in there. Well, that caused me to probably react a little differently than I probably should have and what I was trained to do, because immediately, I jumped off the apparatus. And of course, back in those days, we rode on the tail board, so I was on the tail board and I didn't realize that when I got off the apparatus to go into the building, I didn't have my, my mask, my SCBA but I had made the commitment to go and she had shown me where where to go. And so I was on second floor, I got up at the top of the floor, and I wasn't able to see anything because of the smoke. So I dropped to my knees, which is symbolic. And I saw this foot sticking up. And so without the mask or anything, you know, I just went ahead and had my prayer while I was there on my knees and went on in and I was able to to get the citizen. However, as I just as soon as I got in the door, the backdraft caused the door to blow shut. By that time, fortunately, my captain and one of one of the other firefighters that was with him, they had seen that I had had gone up up the stairs. And so they were following me and I heard them calling my name. And, and so I mumbled and tried to make as much noise as I could and still, you know, obtain obtain my oxygen. And when they realized that I was in which apartment I was in and they kicked the door in, and at that time, I had the citizen on my shoulder and came on out and was able to carry him just to the top of the stairs and then that's when I was relieved. And I took the time to regurgitate and that was a Fortunately, my captain Oh guy named Dirty Trimble, and Dirty called my wife that night and told her what had happened. And when I got home that next morning, my three year old son met me at the door. And he asked me says Daddy, Are you brave and that was a greatest reward I could have could have ever received I did receive the Distinguished Service Award for that. But that reward from that three year old who now is a captain currently with the Dallas Fire Department was very special.

Chuck Hampton:One of the other gentlemen with us today is Baron Temple who joined the department in 1978. Byron What led you to career in the fire service.

Byron Temple:It was funny I started off on the police side. It was while I was at North Texas. I quit the basketball team and somebody told me about the cadet program with the police department, and it's a boy 20 hours a week and to get half the salary scholarship. So I started doing that. And then I turned over became a police officer. But I was 21. And they gave me Monday and Tuesday night off working Midnight's you. And I was a party and Monday, Tuesday and I saw my brother was working at the airport DFW Airport. He said he'd come out here, get dual train, police and fire, and then try to go into what I wanted to be a sky Marshal. And that's okay. I like that. So I left Dallas went out the airport got trained. We'll do a cat, another Academy. And after that came out, that's when they came out with the magnetometers. And they will he had to go through the metal detectors and they got the cameras and everything. So they got rid of the sky marshals. So now I'm at the airport and I'm hating it out here. And we'll be Cornell. He left the airport one to Dallas fire departments may think about being a fireman, fireman this man you work 10 days a month I will then the light bulb came home. Waiting 10 days a month is everyday going is Friday. I said good. I went ahead and went and talked to a wilts Bailey. Two and a half weeks later, I was hired on

Chuck Hampton:what rookie class were you in? 182. Okay. And where did you go out of rookie school?

Byron Temple:24s. Oh, yeah. I mean, I was petrified. I didn't know any. I mean, I got over there. And we had a fire right off the bat. And I heard him on the radio pulling up. We got two ducks in the pond and I didn't have a clue. And that was his you know, he always had an acronym for a two alarm, Three alarm fire. Yeah. And so he would come out with saying the alarm office knew what he was talking about. And I was like, what's going on? Yeah, he was. He was some character.

Chuck Hampton:Ducks on a pond. Yeah. Wow. And so were you there long before you went to paramedic school?

Byron Temple:No, I was only there for about a month and I sent me 55's. And it was like, night and day. I went from being super busy to, 55s where I think my first five shifts we didn't make a run.

Chuck Hampton:Yeah. So who would have been the officer at 55? March? Okay, March.

Byron Temple:It's March. Yeah. Yeah, he was great guy. Wait, I mean, I had back then they were big into playing cards. Oh, so my job was to stay up front. answer the door. answer the phones. Because you know, that's all I do.

Chuck Hampton:They played cards while you were doing that.

Byron Temple:They did.

Chuck Hampton:there wasn't any money exchanged in those card games was there?

Byron Temple:It was big time card games. And his wife would call 50 times a day and disrupt the game. I mean, Marsh told me cuz I played a bunch of basketball back then he said, I'll tell you what. Anytime you have a game on, you stay up there all day and answer that phone and tell her that he's out on the run. She finally caught on and said wait a minute, he can't be on that many calls. She was hot.

Chuck Hampton:So after being at 55s a while, I would imagine paramedic school?

Byron Temple:It was funny because it was a Friday evening and the mainline rings and cap answers it and then he said okay and he hangs up and says be at EMT school on Monday. I asked him where and he said "I don't know". I'm going out there to you know, they told me to park over there with the clinic was Yeah, you know, cross street. And I was all over the hospital trying to find that letter supposed to be I finally found it. And as man this is crazy and they told Okay, you go to primary school, then you go back to the station. I said okay, I can I can deal with that. So what paramedic school we got through now, EMT school, we got through that Friday again. They told us as we're leaving to be back Monday for paramedic school, as well so much for going back to the station. We went through all everything just right through.

Chuck Hampton:And so where did you end up right in the ambulance?

Byron Temple:Went two shifts to 34 I never saw the ambulance didn't speak to me nothing. I mean, he just told me to your on this and he just you know whatever. Wow, let me so I was in my little corner and just, you know, just a to myself and it was horrible. And at that time you got your vacation by how much time you had on you take you five shifts. So I came out got over there. In February, and when I came in that third shift is where you're on vacation. I Li go home, all five shifts to come back from five shifts. And they said, Well, now you've been transferred. Nobody called me. Wow. And they transfer me to elevens. So, I'm leaving from 34s and get to 11s.

Now it's about 07:15 and King Carl is eating my ass out for being late. As a recap, I said, I went into the station over there. They didn't even tell me until a few minutes ago that I've been transferred. Nobody told me nothing. They had to call you. I'm telling you cafe nobody called me they didn't tell me anything. And so, or he, he rode me for about two years. I mean, I could do nothing right. But that was everybody. I mean, that was one thing. He was not prejudice.

Chuck Hampton:Yeah, he hated everybody, equally.

Byron Temple:Two years later, I could do no wrong.

Mike Otto:I'm curious. You mentioned 34's those first couple shifts, and nobody's talking to you. I mean, literally?

Byron Temple:no talking. They told me what I was riding. And that was it.

Mike Otto:Interesting. What was your perception of that? At the time? If you don't mind me asking him he just was he just, this is the way we treat our rookies around here.

Byron Temple:Well, after I got to looking around, I found out only I was the only person of color on all three shifts. I kind of figured out what that was. You know, but I wasn't going to lose sleep over it.

Mike Otto:Right. Right. Right. Okay. Interesting. I just wondered what your perception was.

Byron Temple:No, I knew they were not very happy for me to be there. And they told me that I couldn't ride the ambulance.. Unless, you know... That's fine. You know, that's what you say. But, okay.

Chuck Hampton:Okay, so you ended up over at elevens with King Carl. And did you end up staying at elevens very long?

Byron Temple:I only stayed there 25 years.

Chuck Hampton:So, did end up being a pretty fun place to work.

Byron Temple:Oh it was great. Yeah, it was. I mean, super, super busy. I didn't realize how busy and how tired I was until I left there. Yeah. And I went to fourteens. And we didn't make runs after seven eight at night. And I was, you know, cat can tell you we and Mike too. We had a little pot gone. Putting $1 a day. And then whoever had to watch when nobody went out. Yep. You know, until that next morning after 10 o'clock. Yeah, you got all the money. And we bought all kinds of stuff with station because nobody ever got that

Rett Blankenship:happened like the first week a guy got it. And then it didn't happen again for years.

Byron Temple:Yeah. I mean, we had a lot of money stored up.

Chuck Hampton:Yeah, because on a typical night and elevens you're going up and down those stairs, up and down, everybody. Yeah, everybody.

Creston Whitaker:What did elevens have a reputation for? rookies or people for the first time coming to that station that there's a window up above the entrance and seemed like a lot of people would get doused as they came in from the parking lot.

Byron Temple:The thing was, it was more than one window. People just always they call it the Phantom. Nobody ever saw what happened. They probably knew. I never would have seen doing it. At one time. I even got up in the bed of the truck. I was laying down in the in the latter bed. When the engine came back in and got to God he was still looking upstairs looking through the bucket on and I was off the top of the truck. Yeah, we had a ball. It was it was a great stage. That's good.

Mike Otto:Great. gazzard jc Anderson, man.

Byron Temple:We got some tasty Anderson stories.

Rett Blankenship:And the water fights were legendary before the remodel. When they remodeled it. Everything was new. Yeah. But it used to be you know, pulling off cross lies and just pulling them up.

Byron Temple:stairs. Oh, yeah,

Rett Blankenship:water just pouring through the pole holes. Because the station was already like 75 years old and disrepair. And everybody thought well, what what's a little water?

Chuck Hampton:So as I understand it, you were paramedic of the Year in 1994. Right? Yeah. Was there a particular incident that you think resulted in that it was just kind of an overall it work ethic?

Byron Temple:Probably overall, because they would send me most of the time some of the worst interns down

Chuck Hampton:so there was a little extra help in order to be able to pass their interns Right, yeah.

Byron Temple:And someone that could, I could work with just about just about anybody you know, you know, so they knew that I was just gonna, you know, blow him off. And you know, I'm gonna give him a fair shot. And I, you know, I enjoyed rotten apples because yeah, I always told him that if you go out, and if you're nice to people don't care if you do something wrong, they're not gonna complain on you. If you treat them right. You'll never have a problem. So if you don't know about a problem.

Chuck Hampton:Also, you worked off duty actually teaching paramedic school or

Byron Temple:another funny story? Yeah, Milan rings, I pick it up. It was a female. And she says Debbie case and Barnum were talking about, you know, would you like to become an instructor? And I hung up as nurses come out, we give them hell at stake. Yes. Yeah. I mean, we wouldn't do anything wrong, you know, but they always, you know, they always thought they were so much better than us. And we will prove them, you know, you know, you're good in the classroom, and we get out in the streets, you know, and then we can really show you some Yeah. So, and then when she called, she had a chief call me and say for me to call her really, you know, for I believe it? Because that's an ain't no way they were asking for me. But once I got there, I enjoyed it. You're trying to help the guys and everything? Yeah, they had some instructors out there. You know, y'all came through. I mean, they just, they could treat you like dirt, because they knew that you had to pass. Are you gonna lose your job? And, you know, I didn't, I didn't like that. So they're trying to help.

Chuck Hampton:So you were actually a paramedic for how many years? 25. And hell, so delivery babies during that time? Batman, is that right? Yeah. That's That's a lot. I understand. Crest may actually have your record of beaten though, how many babies to do the liver crest,

Creston Whitaker:I delivered 16. Well, I think what what was unique back in that time was that women didn't have the type of prenatal care that they have now. So it and I'm sure, Byron you agree that it was wasn't unusual for a baby to be delivered every week, you know, within the Dallas Fire Department somewhere. But one of the unique things about it was that after I had delivered this one particular baby, and if in fact that was in in the bedroom of their house and wasn't even in the ambulance, you know, it was time but at any rate, the hospital Methodism, Colorado, unlike any other time before said that I had to sign the birth certificate, because normally the doctors you'll they'll do D and C, whatever. And they'll sign it. And they cure that birth certificate out to the fire station. I signed it, they gave me a copy of it. And I have it to this day on my wall. But because the fact that I haven't I retained the birth certificate. I knew the name of the little girl 13 years later, when I was substitute teaching at a junior high school, I saw this name. And after the class, I called the girl up, and I asked her I said, Where were you born? She said I was born in home the paramedics I'm a paramedic and to this day, we have main contact. She is a mother now and she has forged a web app she has a grandchild now but but that was really special and cherish that moment that all because they required me to sign the bursted. I've never I've never had it happen to me before until that one particular time and they they carried out to this fire station. So that was pretty special. Yeah.

Chuck Hampton:So what about on the trauma side of things? A lot of shootings and stabbings phone 711

Byron Temple:Oh yeah. It was therefore a stretch probably in the 80s Every weekend, there was a shooting or stabbing all of them down maple. We had two sets of projects that we answered also. And it was what was unique about 11th you have some of the richest people in the scene along with two sets of projects and within about three miles and it's just, it's just unique. You wouldn't ever say that you got out of Turtle Creek and they got houses with wooden garages, I mean with the elevator, and then you can go right across 75 right there and projects.

Mike Otto:And so it's interesting. Nowadays, you know, the city of Dallas is homicide rate has been hovering at a little over 200 I think for the last several years give or take up and down a little bit. But that 80s that you refer to when we were actually setting homicide records. We have over 500 homicides within the city limits of Dallas for several

Creston Whitaker:years in

Byron Temple:a row posse was here to the big game. Remember making a posse when they came drone In fact, you remember when he got into shoot out the leader of them and killer and then they took put them in Parkland. And remember they came storm the hospital to break them out. And that's when they finally went ahead and got gone to officers in Parkland because of that. They came into shooting I mean, David was shooting them out trying to get them out the hospital. But I mean it was every weekend. Yeah, they would. It was a violent city, it would make examples out of people. Like if you did them wrong with the drugs. Like I remember over in South Dallas who made that one wrong. They stacked about seven of them in the bathtub. And one of them was alive. He played there. And we know we were just taking bodies off. And then you know, he kind of opened his eyes and it scared me like I don't know what but he was alive. Wow. But they and then we had one over projects over off kings. He was a friend of one of the running backs of SMU and they met to kill him. He had a 300 zx shot on 16 times but it was his buddy wasn't him. Oh, wow. SMU kept saying that he was leaving the team for personal reasons and stuff now they were hot. They come running back he came in right after.

Chuck Hampton:Where did you mostly ride down Blitz crest.

Creston Whitaker:Primarily threes and sixes. Okay.

Chuck Hampton:And I calls it which are always like neck and neck. Oh,

Creston Whitaker:yeah, they were they're always up there. And again, back at that time, I'm sure you can relate to that. It was a lot of lot of trauma calls anyway. But but there wasn't any automatic dispatch of the police. You know, if you needed the police, you would call them. And I can recall an incident where we had a man had that had been shot. And he was on this. He was on the sidewall. And so the My partner and I rolled up, and of course, there's always a crowd of people, you know, for shootings, stabbings, things, or maybe 5060 people, you know, standing around waiting on the cameras and wave is in. But at any rate, we went up to the patient, and sure enough, he had been shot and my partner went back to get the stretcher and, and the patient was conscious. And he was talking and I was trying to find out what had happened or and he said well in it, we just did it all of a sudden and we just kind of disoriented but which I could understand. And this guy kept coming up to me that was on the sides. And is he going to live is he going to live you know and say please, you know, please stay back and give us a chance to assess him and is he going to live is he going to live and after the third time, you know to get the gaff my back. I said I think he's going to make it. The guy pulls out his gun shooting. He was the guy that had originally shot him and he finished him off. And from that moment on, and once we reported that incident, they started dispatching police, police for shootings and stabbings and things automatically. And I was the sixes at that time and and it really because when that incident happened I immediately you know of course called for the police and started backpedaling myself and the guy didn't do us any harm at all. In fact he laid the gun down and remain there until the police arrived. Wow, he just wanted him day.

Chuck Hampton:That was actually my next question was do we know why he wanted? He may have had a good reason

Creston Whitaker:for that. I didn't know but Mission accomplished.

Rett Blankenship:Biron Is it true that I wasn't that elevens when they started the random drug testing, but I heard that you weren't too thrilled about it happening, that they come in there and wanted you to give them a sample and you came back with something different than what they wanted. Is that true?

Byron Temple:It wasn't that I was not happy. They were trying to kick somebody at our station. And they wouldn't admit it, because they just kept coming back. And you know, like, some stations might get tested once. And they came to our stations like four times in four months. Hmm. And you know, who they were trying to get? Yeah. So she told me that, you know, go give her a sample. So I went, I bought some mountain dew. And so I went to the bathroom. And I got a little pebble. And I dropped it in there. And I came out I was shaking. So I think I just did a stone that she looked at the color board and she was hot. Go back in and go into my regular. So much we even knew the first night. Wow.

Chuck Hampton:So you rode for 24 years 25 you rode for how many years? I was

Creston Whitaker:a paramedic for 13 years.

Chuck Hampton:13 years. Okay, we just still quest, especially at that time was a pretty long time, I would think.

Creston Whitaker:Yes. Yes. I fortunately, I promoted out when I, you know, made Lieutenant then.

Chuck Hampton:And did you go to a 780 job or what was your first lieutenants position?

Creston Whitaker:My first lieutenants position was at at a fire station itself. And, in fact, it was doubted 40 threes. And and again at that time, lieutenants were not shift officers themselves. Every station had a captain and a lieutenant even if there's a single company house. And I was blessed to have a great, great Captain that kind of schooled me along. And and I think that that training was was was very, very important and a key to do me developing the confidence and things because I don't we mentioned earlier not but when Byron and I both first came on in in 7879. Long in there. I mean, there were no black officers on the department. And there were a few when when when when I became Lieutenant but but at at that time while I was at 40 threes, then they decided that they were going to allow lieutenants to go to stations and actually be the shift officer. And if it's a single company house within there be one captain and two lieutenants on the other shifts. And so I had the opportunity to go to 50 ones and, and I was a shift officer. And that was a real gratifying, challenging situation. Certainly, though, as a lieutenant.

Mike Otto:So grass there a minute ago, you mentioned captain of 40 threes, it really mentored and helped you as a young officer when you just made lieutenant. Could you tell us who that was? Yes, that

Creston Whitaker:was Captain Gary level. And he really spent a lot of time with me. And I'll never forget that when when I left 43 and that was the time when I was assigned to 50 ones a station as the shift officer and I would be responsible to manage the shift or supervisor shift. And I remember Gary turned to me and he says question. Now when you go over to that station keep in mind that that station was running fine before you got there. That was the best advice I could ever receive him, you know. And, of course, what he was saying is don't try to reinvent the wheel or anything like that, you know, just make changes that are needed. But But, you know, just be practical about how you handle things. And when you do make changes that that they are necessary changes. And anyway, I certainly appreciated that advice. I've never forgotten that.

Rett Blankenship:You mentioned him being or helping you out a lot. For both question for both of y'all is, who did y'all find his good mentors in the department people that you really looked up to? Who, who impressed you and gave you some good insights on how to survive in the fire department or bored words of wisdom or,

Byron Temple:for me, people won't believe it, but it was actually was King Kong. I mean, they will people on the department that if they could, they would kill that man. I mean, they hated him. And when I worked there at first, you know, there's no way I you know, I hated them, too. But I learned so much from them. And from what I learned from him, I knew what I couldn't what I couldn't do. And that's what you know, I knew, like I said, if I went somewhere and I wouldn't treat it, right. I knew how to get around it. You know, I could do all the way up to that point where, you know, I'll keep me from getting in trouble. But now, you know that I know what you're doing. You know, so I mean, he, he really helped me a lot. I mean,

Rett Blankenship:anybody else that comes to mind? You're good? Oh, no, no, no. We got more than one person. I don't mean.

Byron Temple:Good. And, but a lot of them tennis came to 11th. And we had some great lieutenants. I mean, Otto was good. David Kenny. And we had some some some great guys come through. And what was funny about David Kenny was he couldn't stand don't cheat, don't cheat, because she thought and Won't you know, he was the smartest man in the world. So it wasn't candy want him to think he was a Thomas man. He came over to do something just crazy. We had a balding lab.

Chuck Hampton:David getting's good. At some point, you made a transition and went to communications.

Creston Whitaker:Yes, I. But Ronan Gamez was the deputy I think at that time, and seems to be that that's when the alarm office change their shifts from three until four, four shifts. So the firefighters in the alarm office, were working toward me for hours, and they would be off 72. And, of course, that appealed to me. And so I remember calling chief gammas and expressing my interest. And he said that, well, there were a few things I would need to do and provide him with the resume, which I did. And about four months later, I was assigned to the alarm office, and I was the first African American officer to work in the alarm office. And that was challenging, because, as you know, Chuck, you work down there, yourself. Anybody that goes into the alarm office, whether you're a captain or are or a non officer, you're at a loss for four weeks or maybe months while you're down there. You know it it is so challenging, and thank God, David Henry, and probably others too. But I know David Henry told me it takes at least a year to get halfway comfortable with this and at least two years to really get good at it. And I think that was true. There's no question about it and David was down there and help assist me in what I was doing and, and and then, probably about six months after I had been down there. The captain that was on the shift I was unable to work and they didn't replace him. And so I was the only officer on the floor during our shift at that time for about a year. And that was was pretty challenging. But that was probably the best tour of duty that I had with the fire department because it gave me the type of insight within the department that I never really had. Except for rookie school. But, but even then it reinforced that because you can see the practical aspects of why an engine goes with an ambulance or, or how calls come in, or why an ambulance doesn't show up on time or, or the confusion on the telephone when people were calling in, you get a firsthand experience in that and so that that really helped me tremendously throughout my career.

Chuck Hampton:Yeah, if you really want to know how the fire department works, that's a great place to see it from the inside out.

Byron Temple:Yeah, I should have been there when there was no Bartell memory, the fire department ran to 87 and living room that they were sitting in. They got eight hour shifts, they leave an alarm office come to the hospital. Yes, a little room, and we call them to them. You know, that was 287 that's what that was. Call Number four. Okay. And yeah, they call it they call them let's calls.

Chuck Hampton:Wow, I remember in paramedic school, going out there and see and there's a dispatcher out there named Glenn Robbins. Do you remember good Robins there was some nurse that was being real nice to me. And kind of cute and glinted, stay away from her. That's the one that got all them guys in trouble. Down in City Hall. Man man

Rett Blankenship:that was back in the days when we didn't get there was no gloves on the ambulance except what was in the kit. So whatever blood or whatever you go back to Bobtail there been a bunch of paramedics sitting around with blood capetonians drinking a cup of coffee.

Byron Temple:If you got bloodied up, it was like going into fire and get smoked. I mean, you were exactly that. Well, that's exactly true. Yeah, it was a sign right that you were real medic. Yeah,

Rett Blankenship:I clean up or anything. Yeah,

Creston Whitaker:I had gotten to the point where, you know, I, the blood and guts was was a problem for me. You know, it used to be you know, a lot of guys, you know, man that that shows your honor and all that stuff. And so I started wearing gloves before the department, you know, administered them. And I had these dishwashing gloves, you know? And it was never time that I'm going into the hospital that those nurses and things why are you wearing gloves? Why are you wearing and I did that happen for a better part of the year? I remember. And then all of a sudden it did. You know he might auto start where you

Chuck Hampton:were ahead of your time? Yeah. the AIDS epidemic. Yeah.

Creston Whitaker:It just you know, cuz I had that thing about I didn't like being in blood and guts and all that stuff. And then I'll never forget that that day. Everybody, the doctors, nurses, all of you. How come you weren't close? You know? And

Byron Temple:the station had the big bang where we do all the Oh,

Rett Blankenship:o da news, the grossest thing Oh, far too far. Yeah. And pretty bad. As they were phasing in gloves. Remember, they bought us every puzzle, or they bought autopsy gloves, but you shared them. They were kind of thicker and bigger than you would like, once you use them, you wash them out and then right? Yeah, leave them for the next year. That way, I didn't have to buy like single mocks. Well, I'm

Chuck Hampton:gonna go back to something you said a minute ago, you're talking about, you know, you'd started wearing gloves before other people did before the AIDS epidemic didn't really like the blood and guts and all and that made me think, you know, as far as you know, people were like, what you know, did did the blood and guts bother you and stuff and to me? It really didn't, but was always eerie to me worse, like, imagine what people's last moments were like. And I'm thinking of like, where I've got somebody a stabbing victim and you see the defensive wounds where their hands are cut into, as they were holding their hands up to try to fend off the knife. And I'm thinking, you know, what was this person's thoughts at this point in time, and I've wondered since y'all both rolled the amulets for a long time. Was there anything that really bothered Did you? Was it the blood and guts? Was it some or something like, you know, seeing children or imagining like I did what their last moments was like, was there anything that ever caused you to lie in bed at night a little bit? And the thinking thoughts instead of getting back to sleep, for me, it

Byron Temple:would be for one kids. That was the hardest call if you had a trauma, or any kind of call on a kid that didn't make it that that's the hardest one. And the second would be if somebody you knew, and we've had I've had to work on fireman, what's his name from threes? I got hit that time, but Oh, yeah. Russell Jones. Oh, we, uh, he took his last breath. And we invaded and brought him back. And he fought us all the way to you know, we got him intubate, he fought us all the way back to the, to the hospital, and those kind of calls that you always remember. And it was before we knew about PTSD. Yeah. And once we started getting that training, right, I didn't think it was really any good until I started, you know, listening to what they were saying. And then I started thinking about some of the stuff that I went through. And it's Yeah, that's true. And it really happens, you know, you think about it. made a call, Keaton rec got thrown out, look just like your son, same age, everything, he couldn't ride them anymore after that, I mean, it really messed him up. So those those two really bother you. And then the other part, you kind of get immune to it and it is bad because you see it so much it doesn't even bother you just go on is like going to Kroger and picking up meat, you know, is it doesn't bother you. And then you bring it home and you know, your wife cut a finger and you look

Chuck Hampton:at that is not this response.

Byron Temple:But you get program like that, you know, he's all you know, just run some water on you know, I need some attention, you know, transport

Rett Blankenship:an open fracture, donate, right? I'm watching.

Byron Temple:Even in high school, we'll play we're playing ball coach told you if you're not bleeding, you ain't hurt. Yeah. And that's how you know we will train.

Chuck Hampton:That's true. That's true. Chris, did you have anything you wanted to add to that?

Creston Whitaker:Yeah, I will always remember the first run that I had as a certified paramedic, and we arrived, and it was a, a small child, probably 12 months, 14 months or so. And the parent had taken the screwdriver and stuck it through, it was actually through the eyeball of that baby. The father had done that, and him and the mother were arguing or fighting and for whatever reason, he chose to do that. And, and I remember riding all the way to the hospital, trying to deal with the to keep the screwdriver from moving any more than necessary. But of course, those of you that are written in ambulances realizes how rough they ride anyway. And that baby was just in so much pain and drama, that I really began to question if this was the profession that I wanted to do or not, because that took an awful lot out of me. Fortunately, the baby lived. It was blind, then in that I of course, but it just was so sad. And to to experience something of that nature. Of course, we had to call the police and they came out and arrested the guy and I think he's still in prison. But some of those type of incidents and as Byron was saying, can make you catalyst in other aspects of your life. But but that's something that I've always made me even more partial course, small children.

Mike Otto:So gentlemen, I've got a question for you. As we mentioned earlier, when Chuck did the introductions, you guys are a couple of African American gentlemen that were some of the first to be hired on the Dallas fire department and I'm some Buddy that is really interested in history and civil rights is something that's always intrigued me, you know, because a lot of that stuff was going on when I was growing up gi man. I know that both of you are very involved with the black firefighters Association, I think crashed you were actually the president of the BFA for a period of time. I think a lot of people are always wondering why why do we Why do we need three labor organizations? Because we have the Dallas firefighters Association, which is the largest employment or employees group, and then we have the Hispanics firefighters Association, and the BFA. And, you know, a lot of people feel I give the three would unite, which I think probably the three do unite on certain things. But if you were to to be able to speak to some of these people that wonder why, why was there a need to form a black firefighters Association? And maybe you could address that, and maybe you could then address some of the advancements that were put into place? Or they were enabled people's careers to prosper? What do you want to be like to speak to that?

Creston Whitaker:Yes, I'd be glad to do share. My my feelings regarding what I felt was the need for that. And to give an analogy, my daughter, and I had a, I have a daughter. And as she was growing up, my wife insisted on her having a black now, which were not on the retail market. It was very, very difficult to find a black Now, of course Barbie and gain and all the doubts that we're not have cover. Now, one who is not of cover might ask the question, well, what difference does that make? It The difference is in the fact that it's important to see yourself in something to progress. When Barack Obama became president, the significance of a African American person saying an African American president provides the type of confidence to move forward and to be as outstanding as you can be. If you grow up, and if every time you turn around, you don't see anybody that looks like you that is successful, then that makes a it makes it very difficult for that person to overcome some of the obstacles that they're faced with. And I think that with the fire department, I think I mentioned before that we were the one of the first classes to have mandatory paramedic school we had to pass. But we were also one of the first classes and Byron you can probably vouch for this, where the city of Dallas had made the decision to hire in in all hirings. At that time, half of the class 50% of the class had to be minority. And either Hispanic or African American or Asian, or whatever the case was that theme female. That half of the class had to be made up of minorities, for the very reason that there was such a shortage within the Dallas Fire Department, police department as well, but and it took decisions and ran procedures of that nature in order to allow people such as myself, who I'm thankful that I had the opportunity where I might not have had the opportunity had there not have been a certain amount of pressure that was put on the city. And this pressure comes from organizations which can promote the benefit of their own. And therefore, organizations such as the black firefighter Association, is as going to address sensitive issues to African American firefighters. And it's just for lack of a better term, it's a necessary evil, you know, to people that aren't of color in this, possibly but but those of us who are African Americans can truly say that organizations like that have allowed us to be able to accomplish and do the things that we were able to do.

Mike Otto:What do you think? Yeah,

Byron Temple:well spec to my experience. I mean, I know guys that might have gotten in trouble, and go to the local 58 and ask them for assistance. and nine times out of 10, they will turn them down. I mean, they just they will not their form. I mean, we were paying money, just like everybody else. And I've seen some guys did some horrible stuff. And they backed them all the way. Then ask them guys do some minor stuff, and they refused, you know, to help them then you're out there on your own. And aggressive alluded to earlier when we hired on, there was no such thing as a black officer. Yeah, it was nobody you could turn to and it was very few people you can go to just ask for you know, any kind of, Hey, you know, what did you do in this situation? What did you do in that situation? You know, you had to learn on the fly. And so if you were the type that couldn't stand, the pressure they put on you, then you're gonna get in a lot of trouble. I was blessed with the ability docket, I was taught my way out of anything. All right, you know, if I want to make you mad, and you're trying to make me mad, I guarantee you, I'll get to you before you get to me. And that helped me a lot through because I went to some stations where I came into situations where I mean, they will just be an outwardly racist. I want to threes one time serving for I'm Sherry Wilson. I mean, how are you? So for each other, went back to school. And that first I got in that morning, and man and samples, he swung in. And I saw the guy walk around asking everybody in the station, how do you want your eggs never came to us. So when they came to eat, when they go eat? And so I picked up a plate, he's way You didn't tell us what you want us, you didn't ask me. I said, I ain't got no invisible ink on me. So those are my eggs. Not right now. These are mine. Just you know, stuff like that. Where was nobody I could go, Hey, you know, they're doing this to me doing that. You had to do it on your own. Now, these guys, they have associations that they know that they have their best interests at hand. And that's why I feel like every association that you know, if you're black, and you're going to an association that doesn't have your best interests. And they think that what you're saying is, you know, there's really nothing, you can't get anything done from that. So that's why I feel like the black firefighter Association for me. Well, I didn't have to use them. But I was used by them to help other people. And I'm appreciative of that. Well, it's,

Mike Otto:it's interesting, I appreciate both your perspectives on that both of you guys. You know, I've known Byron for years, you know, and, and I've known of graston for years. And both of you guys have, you know, stellar reputations, you know, amongst all your peers in the in the fire department. And I think, for the listener that that maybe had never considered those perspectives. I think it's a hopefully, it's eye opening, you know, to sit back and try to look at things through somebody else's field of view.

Chuck Hampton:Chris, before we started the show today, and before we had turned on the recorder, you had answered a question, I think read it asked you, you were in it spun off into a story about something that happened to you once involving a noose. And I thought that was interesting, as wondered if you could recount that story for our listeners.

Creston Whitaker:Sure. Early on in my career very early. I was at a station and having been there for maybe two shifts or three shifts. In fact, what was what really struck me as being strange is that the captain of that station never spoke to me for three shifts. It was it took three shifts before he ever acknowledged me. He never said hello or what have you. But at any rate, I had gone to to my bed and on my bed was a hangman's noose. Now, when I saw it a year ago, I had to to try to think it think it through because my first reaction it made me very angry. But then I got to thinking that well, maybe I can use this as a learning experience not only for myself But for the people involved in, so what I did is that I simulated a hanging with that news with the chair and I made it look like I had hung myself so that when they came back to the bedroom, the first person that saw me was screaming and hollering and ran over and grabbed me in hopes that he could save my life. And of course, as he was touching me, and then the others were coming back to the bedroom, then I was laughing as well. And that moment was so special, because they realize that it was not good judgment on their part to do that. And, and we became best friend from that point on. And I think that they learned a lesson from that. And the lesson I learned is that if sometimes if you take the high road that you can resolve a situation much better than then just allowing your bitterness to, to take over the situation.

Byron Temple:I have come across some guys that I've became good friends with. And once I got to know them and start talking to them, finding out that they've never worked with a black person, and they've never gone to school with a black person. And it was totally different for them. And I come from army background, my dad was army I was used to, you know, integration. So I didn't see that. And but they still some of them to this day, you know, they still look down on you, like, you know, I'm still better than you. And you know, I kind of it kind of bothers you, when you really looking at the weight right now I trained you, but you better than me, you know, and you have to look at them and you just shake your head. But if some of them, they just they're oblivious. They don't they don't have a clue that

Chuck Hampton:they are and they may be oblivious, because of that lack of integration. But I think also maybe, in some cases, a lack of education. And I'm going to tell a story on myself in that regards. Mack Otto and I were in rookie class two or three together. And there was an incident where a white member in our class made a noose, I think probably out of that rookie rope or something. And then one of the black members in our class got offended. And so these two were, you know, having a big verbal fight nearly came to blows. I didn't understand why I didn't understand what the issue was. I didn't understand why a hangman's noose would be offensive to anybody. And that was literally a hole in my education, you know, the ad just literally didn't have any understanding of the cultural background and issue there. So. So unfortunately, we've got a lot of history to learn.

Creston Whitaker:I think, if I could mention, Chuck, that one of the the reasons that has allowed me to possibly be more objective than then maybe a lot of African Americans might be because growing up in Illinois, I had always gone to integrated schools. The first time that I had an African American roommate was when I came, went to college and came to Texas to go to college yet, because I was always in an integrated environment. In high school, I was the only African American on the football team. And we went and played this other school out of town. And after the game, went to the restaurant, and the restaurant owner told the coach that he couldn't serve me in the restaurant, the coach without batting and I said, Well, if he can't eat in here, none of us will. And the whole team got up and left now have that had that have been handled differently. That would have affected my life in a much more bitter way. But even though it was a hungry ride home the fact that all of my teammates came to me and put their hand on my shoulder and told me that dog honored it's worth it. You know, that, that the guy was wrong to do that. And then, I guess to this day, and he's probably recognizes that just how negative there's something like is, but I've, I've always remembered that and how I failed. And I just try to imagine how I would have failed. And I have eaten on the bus and the rest of the team have eaten in there. At my 50 year reunion, I went up to that coach, and told him how much I appreciated him handling it, as he did. And him and my classmates all remember that very vividly. It was a lesson for everybody.

Mike Otto:That's exactly what I was just sitting here thinking that it was a lesson for anybody that wanted to learn a lesson that day, you know, and I think there's good people out there, you know, and they're all they come in all, you know, colors and shapes and sizes. And we have to keep that in mind. And a little empathy goes a long way. And in trying to, as you I'm sure your teammates did put themselves in your situation. Wow, wouldn't that suck, you know,

Creston Whitaker:and we're at such an impressionable age, I was 15 at that time, you know, and, you know, teenager things, and that's an impressionable time in a person's life, trying to find out who you are, and, and I just, I thank God every day for, for that experience. And that's what allows me to simulate the hanging and that type of thing if I can teach somebody else or show them or find a way to come together,

Rett Blankenship:yes. Was this an Illinois or text? Now this was in

Creston Whitaker:Illinois. Yeah. And even though we, like I said, we, our school was integrated and things but I mean, there were issues and you know, I had some some experiences that were unfortunate, but but as far as on the surface, as far as going to school together, and working together and things that it was an integrated society. But I didn't go to a lot of the parties for some of the people that weren't gonna

Byron Temple:tell him where you're from Otto?

Mike Otto:Oh, I'm from Indiana. And, yeah, we've got we had our issues. Yeah. Well, my grandfather pointed out to me, and of course, this isn't about me. So I'm only this I'll just be brief. But he, he showed me as a young man, he showed me the township charter in which I lived in which blacks were only allowed to live on this street between the railroad tracks on the east and Thompson road on the west. And, and when I was in high school, I realized that's exactly the way it was, it was still that way in 1976. And that's something that really got always got my wheels, churning, you know, and thinking about the things of course, leaving through the 60s and and MLK his assassination and the civil rights struggle and, and Bloody Sunday and whatnot. Anyway, I don't want to get off track here. But I know that it's a significant part of you guys's lives and legacy. So I just felt like it was something that, you know, you might want to just comment on, and that the listener can walk away from possibly this podcast has looked at things in a different person.

Creston Whitaker:Thank you for that.

Chuck Hampton:So looking back over your career and the things you learned, sir, any words of wisdom you'd like to pass on to maybe the new guys that are just coming on the job?

Byron Temple:Yeah, um, probably the two most things that I regret. One was, was applying myself and studying. And that was my fault. Because I was, I mean, I had so much fun in 11th. I didn't care about making you know, also my second driver. I was good day, I just had a ball. Wish I had studied and applied myself for promotion. And second thing was, I would tell everybody, as soon as you come home, as soon as you can max out your 401k. I mean, because, I mean, I didn't do it till about my last 15 years, and it was good. But I've seen some guys that did it 2025 years, and they have more than four one they'd have to drop in and reminisce. This is one thing I wish you know, other majors want the party and didn't care about anything but that day Couldn't you just force in that? Those are two things that I really wish I'd have done different. Yep. But other than that, I mean, it was, it was it was a great run. I mean, I didn't come in thinking that I was gonna enjoy it. I came in because the days off to tell you the truth. But then I found family. And it elevens man, we I mean, we will. I mean, we will close. We did everything together. The new guys now coming on, they don't do stuff like we did. If we went out, like, we're going to go party, everybody went, we'd have picnics together. I mean, we did everything together in the guys now, the more like the police department where they just come in and just leave. And that's one thing I did learn about on the police department. What's so hard about that job is the public that like police, firemen, and policemen don't like each other. I mean, you don't see groups of policemen just hanging like you will fireman, have you ever noticed that? You won't say I'm doing that. And they just, and that's what I just, I was just blessed that I did become a fireman. And I really enjoyed it. I had a great time and learned a lot in undergrad and a lot of great people.

Chuck Hampton:That's great crest, any, anything you'd like to pass along?

Creston Whitaker:Yes, much, much like what Byron was saying. My initial reason for joining the fire department mainly had to do with the time off. But it didn't take long for me to realize that. That this was going to be one of the best decisions I've ever made. And now that I'm retired, I can confirm that it was the best decision that I ever made regarding my, my career and in my life.

Unknown:The

Creston Whitaker:fraternal relationships and amongst each other, is just so special. And I think that as a, as I did promote, it gave me an opportunity to, to learn as well as, as to lead. I always wanted to lead and provide leadership but but one of the things that I think is extremely important to learn, and that I learned is that rank and rank and intelligence don't run parallel. I think that you, you have to realize that just because you're a an officer doesn't mean that you can do something that private can't do. And I think that's is a great lesson for any environment to realize that you have protocol and paramilitary organizations, but ranking intelligence don't run parallel. And but I'm thankful for the experience and so thankful that that I was here in Dallas, and the friendships and even the the the negative experiences that turned into positive such as think I mentioned earlier that this Captain never spoke to me for three shifts. The first three CSR was there. But around the fifth shift, when we had a fire, he grabbed me and said, stay with me, son, I got your cover. And that's that's what it's all about is that? Well, we have the Brotherhood or sisterhood that we have within the department is so so very, very special. And I'm thankful that I experienced.

Chuck Hampton:So tell me tell me what happened on October 29 2019. I

Rett Blankenship:wouldn't I wouldn't like

Chuck Hampton:it was a bad

Creston Whitaker:rule in my heart stopped beating three times. They revived me three times. I was going to work out at the Y over on Hampton right down from 40, nines and 40s. And I went in there and I felt a little queasy. And one of the trainers it's there, you know, because I go in there I'd go in or three times a week but he said that he said question you're right. And you know I mumbled something. And next thing I knew I was sitting in the ambulance they went ahead and called the ambulance because I had started to pass out or vomited. When I was in the ambulance was just in there long enough conscious to, to say, can you get my keys out of the locker and then boom, that was it. 14 was ambulance that pick me up, and they transported me to chart Methodist, which was the closest hospital when I got into the emergency room a heart stock. They had CPR and and I survived that. They've sent me to the cath lab cath lab. And after 12 hours in the cath lab, my heart stopped again. They CPR. Wow, Robbie back. They sent me to ICU. And by that time, the doctors had told my wife and said, Well, we don't think he's gonna make it. And heart stopped again. Third time. And then mysteriously the what came to the doctor's mind. And even even he and she the the two doctors that were there, acknowledge that it was it was a deal that state credit for the Lord, you know, he was he was controlling this. But he had this thought, why don't we get a bigger pump heart pump. So they, they didn't have one in the hospital the size that they needed for me. And so they sent all for one and Baylor gave them this gigantic heart pump. You know, it was a biggest drop Methodism ever put in a patient? And I asked him as well, why was that? You know, I mean, I didn't ask him at the time.

Chuck Hampton:after the fact, yeah.

Creston Whitaker:Yeah. And, and he had said, he said, My heights had a lot to do with him, you know, being so tall or what have you, but I'm sure there's taller people than me. They had heart attack. But anyway, when they installed that, you know, my heart's been ticking ever since. And, of course, that has become my testimony is the fact that the good Lord just said, Well, I'm not ready for you yet. Chris. Uh, you know, you got some work to do, you know, and that's what I've been doing. And I share that story with with everyone that that I come in contact

Chuck Hampton:with. That's amazing. How are you feeling now?

Creston Whitaker:I feel great. I've started working out again, you know, I can't do what I used to do, but able to do to work out. And 40s had a fire department coordinate with them and things that they had a kind of reunion for us to come together. Which is really nice. So you got to

Chuck Hampton:see the paramedics that Oh, yeah,

Creston Whitaker:yeah. All the the ones that were on the call and the engine groups.

Byron Temple:And we did at the time and say your son's late 40s.

Creston Whitaker:Yeah, yeah, he was at 41 his shift. But he was at 40s. At that time.

Chuck Hampton:What a twist, you know, from all those years on the ambulance, well, yeah. Created by a fire department.

Creston Whitaker:Well, that that was the point that I was making is that I've been on the other side of it for so long. Yeah. Now I found out what it's like to be on the receiving end, and how important it is and and it was from those guys in handling me like they did. Yeah, because you know, when CPR hit by the time I got to the emergency room, you know, it? Obviously they prolonged it enough to where I can make it to that, but

Rett Blankenship:did they know you were a firefighter at the time I retired?

Creston Whitaker:Yeah, they knew when they saw my name and things because my son was even though we have same name, then they they realize that and wow, I just, you know, just so thankful for that opportunity. And no, my wife passed away. Last year, on Mother's Day. And my daughter Chelsea is the one that founder because I had left left the house for something and she was bringing flowers and food over to for Mother's Day. Yeah. And my wife was was in the bathtub, you know, unconscious or she passed away. And and my daughter who is a undercover officer with the Dallas she works the US Marshals

Byron Temple:basketball player. Yeah, really. I know. She is pleased. Yeah, okay Miss Bailey Yeah,

Creston Whitaker:yeah. And and got her all agree this past December one last good friend and she told me she said Daddy, I thought I'd seen it all but I you know it in Jen she's been undergoing therapy and things you know from that and of course my wife was there when I had the heart attack and things and of course she's a strong Christian woman anyway so, you know God was ready for her but but I think the key is that you have to true believer has to accept God's will. Yeah, without understanding, you know, we're not we're not going to understand those things until deal that day that we're there you know, when when when we go home, and but to be able to accept things that you don't understand is true, is the true challenge.

Chuck Hampton:I'd like to thank Byron and Kristen for joining us today and sharing their stories. It was one of the great privileges of my career to be able to work with so many great men and women that I really consider just the salt of the earth. These guys certainly fit in that category. A couple of notes. For those wondering why there was laughter when Kristen mentioned at the Milwaukee Bucks signed Lew alcindor instead of him. Lew alcindor is better known as Kareem Abdul Jabbar. Also, I want to stick a Do not try this at home warning label on this episode for all you young and still working. I refer specifically to tamper with drug tests, which will get you fired faster than who'd a thunk. And also be careful about going overboard on waterpots. And for Pete's sake, don't gamble at the station. In fact, don't gamble anywhere and you'll be better off. Apologies for taking a parental tone. But it comes naturally because for most of the years of my life now I have either been in the role of parent of children or in the role of Chief, both of which are frankly, exactly the same thing. As always, there's more information on the website firehouse talk.com, including photos of today's guest. And if you'd like to reach out to me about a story idea, you can send me a message there or on social media. For those who don't know, the Dallas firefighters museum is open, check out the museum's website at Dallas fire museum calm for current operating hours and other information. We've got some great docents. We'll be happy to give you the grand tour. Until next time, y'all stay safe out there. That is all kk in 377 fire departments city of Dallas.