Talk About Cancer

Talk About Cancer is a podcast of stories from cancer patients, survivors, caregivers, and family members. The host, Serena Hu, talks to her guests about their emotional journeys with cancer and what happens to the relationships in their lives after a cancer diagnosis. They sometimes explore how culture and faith shape each person's experience of cancer and grief. You will find diverse perspectives, honesty, and wisdom in these stories to help you deal with cancer and its aftermath. http://talkaboutcancerpodcast.com

Talk About Cancer

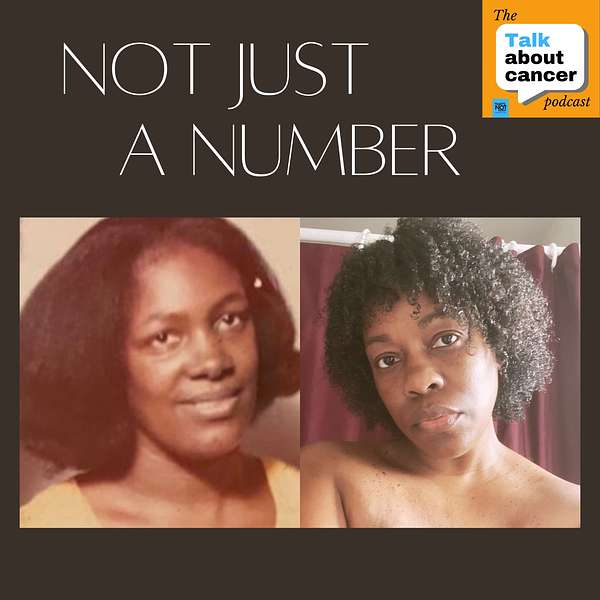

Not just a number

Shoni gets vulnerable and candid about her mom’s and her own experience with cancer and why her voice as a Black woman, matters.

You can connect with Shoni on Instagram @brsuga and learn more about For the Breast of Us on their website.

Please follow the podcast if you are enjoying the show. Would also be awesome if you can leave an honest rating and review so I know if I am serving the interests and needs of you listeners out there.

Have topic suggestions or feedback about the show? Contact me on Instagram or email me at talkaboutcancerpodcast@gmail.com.

Thank you for listening!

++++++++++++

My reflections on the conversation:

After our recording, I thought a lot about Shoni’s experience with the receptionist at the oncologist’s office. It’s the kind of experience that is so familiar to those of us who have had to navigate the healthcare system to get care for complex medical conditions. But it is even more stressful when you know that by speaking up, you will be labeled and dismissed with a negative stereotype, like the “angry black woman.”

These kinds of stressors, even if seemingly minor in isolation, add up over time, and not just in healthcare, but across all kinds of important areas in life, such as education, work, and housing. It’s therefore not surprising that minority groups have less positive health outcomes - living with cancer is completely overwhelming as it is, so some days you just may not have the energy to get over the extra hurdle thrown at you. But that sometimes can make all the difference in your trajectory.

A big shout out to Shoni for bringing to life what we read about in research papers and textbooks. You are not just a number, and we thank you for helping us see you.

Hey everybody, welcome to episode 25 of the Talk About Cancer Podcast. This is Serena. If you've enjoyed listening to the show, don't forget to take a moment to hit that follow button on your podcast player. Also, I'm looking for more people of diverse backgrounds to share your cancer experience with our listeners. Please visit TalkAboutCancerPodcast.com to get in touch with me if you're interested or have suggestions for guests. In today's episode, Shawnee gets vulnerable and candid about her mom's and her own experience with cancer and why her voice as a black woman matters. Let's dive into her story now, and I will check back in with you at the end. So welcome to the Talk About Cancer Podcast. Let's start with a quick intro and have you tell us a little bit about yourself, who you are, where you're from, and anything else you would like to share with our listeners.

SPEAKER_03:Hi, my name is Shawnee Brown. I am a cancer survivor thriver. I am from New York, actually from Long Island, New York. Um, and I'm actually coming up on my um five years cancer-free in about another two months or so. So I'm excited for that and a little nervous at the same time.

SPEAKER_00:What's with the nervousness?

SPEAKER_03:Um because it isn't here yet. So it's it's like it's hard to celebrate something that hasn't happened, and I don't know when it happens if I'm really going to be able to fully absorb that it's happened, because I know a lot of people who got into their literally their five-year mark and reoccurrence was like right at the door. It just like opened the door as soon as that door closed, and you know, it it's scary, even though it should be a time where you say, Okay, this should be okay, but there's never an okay time frame because it could be 15 years from now, and I still could get a recurrence because that's just what cancer does.

SPEAKER_00:And can you tell us a little bit about how cancer entered your life?

SPEAKER_03:So I would start with my mom at the age of about 21-ish. Um, my mom had already been s like sick for most of my childhood um with just a lot of gastric issues, and so when I was around 21, I was graduating from um college, and and my mom started to not feel well. And she went from doctor to doctor, and it was a total mess because they just completely dismissed the fact that she was not feeling good. I saw the gut-wrenching pain in her face when she sat there and told doctors that her stomach hurt, and they just wanted to give her like pepsid or some kind of like here, it's like giving a tic-tac to, you know, when you have a painkiller instead. It's it it just was it was mind-boggling to me, and it was just across the board. It was just door after door of doctors just dismissing her, and it was hard to see as that's being my mother, and you know, being this young also, because they also dismissed me because I you're young, you're dumb, you don't know what's going on, and they also like basically talked over us and only to my dad. And that was hard because I was with my mom a lot. I went with her doctor's appointments between my sisters and I, and it was just hard that they didn't understand that we weren't stupid and we didn't get it. And I feel that a lot of the times when it comes to medical professionals, they don't let themselves be as transparent as possible because they think that they're saving feelings or saving your hurt. No, I'm still gonna hurt, but I'd rather know the truth. I don't want you to sugarcoat it, just feed it to me exactly how you need to, and I can process it the way I need to. And so it took them probably about a year or so to really diagnose her. And by that time, she was already metastatic and the cancer had spread. So I went through taking her to um chemo, and that really didn't do much for her because all it did was the side effects it gave her were worse than what she was already feeling. And my mom already had what's called sarcadosis, which is an autoimmune um disorder that presents itself as um almost like welts on the skin, it looks like it hurt, but it for some reason the chemo made it come out and and it was more active at that time. So dealing with cancer and the sarcadosis, and it was a lot of it was has to do with the breathing, and it was just a lot for her. Um so they just after a while it was okay, so let's try to remove the cancer from the pancreas. But because the pancreas is such an interesting organ that people don't realize that there's so many um blood vessels that are involved, and if it is anywhere near a blood vessel, they're not going to remove the tumor because then it it would cause bleeding and so many other things that would happen, and that's exactly where it was. It was right where it didn't need to be, and um that's what happened. They opened up and had to close her, close back up, and I feel like that also progressed it. So it was like from that time on, it just was like lights just flashed and it started to go downhill. Um, where they started to say more things like being comfortable instead of this is she's she's dying. And then they eventually just said, you know, she's has got six months or so to live, and she's like, No, this is not gonna be it for me, not six months. Um, she made it around to one more of everything except for my birthday. So that year, it was 2003 on March 5th, about two weeks shy of my birthday and lost my mom.

SPEAKER_04:And I don't think my life has ever been the same.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah. It's really hard to hear. Also to your point about just being so young at that time, and then to all of a sudden have your mom, which is, you know, at that age is still everything. Absolutely. You still expect them to be the rock, you know, that you lean on for what else is to come in life, right? So just having gone through that process with your mom, how does she talk about that with you? Was she sort of trying to protect you and be like, it's okay, right? Or was she also just being very transparent? Like, this is such BS.

SPEAKER_03:She was transparent. She was she was scared, I could tell, because she's just like, I know something is wrong, but I don't know what it is. And at that time frame, pancreatic cancer was not something they talked about. And I kid you not, it must have been that year later on that I saw like commercials under the sun, like everything was pancreatic cancer because they were now starting to realize that this is like a silent killer. And we did talk about things like as far as you know, she told me when she was tired. I knew it when it was time. Um, to be honest, I did. I didn't want to hear it, um, because I just really wasn't ready to let go, but I knew she was ready to go.

SPEAKER_00:Did you tell her that you weren't ready? Or did you kind of keep that to yourself? Because you were trying to honor the fact that she was ready.

SPEAKER_05:Even though she was. You know, no the hell it's not. You know, I'm gonna keep fighting until I just can't do it anymore.

SPEAKER_03:And it was probably like I wanna say the week that week of I was in my like one of my last classes because I was um finishing my teaching um certification and everything like that. So I was you know, my professors knew what was going on, but I was still going to my classes and you know, visiting her. At this point, she was in um hospice, and I didn't really know what hospice meant at that time either. So that's one thing that they were not as transparent as they should have been until I looked it up after the fact when she was there, and I'm like, okay, this is what this means. Um and she was fine, she was talking and she was coherent and understood who was there. And the day that she told me that she was tired was probably the week before that, and I had been still coming to just literally after class, I was at the hospital, and one day I didn't go, um because I was just so tired and I felt like I'd been in the hospital for months, because it had been like two months at least. And like I for years beat myself up because I didn't miss that day, because that was the last day that I could have spoken to her when she knew who I was and then the next day she was gone. But I feel like she knew that like it was her best friend was with her in the hospital, and um, you know, all of us were going to work and school and everything like that, and this was our best friend that she had traveled with and everything like that, so I think in a sense she knew it was easier for her to let go then than in front of us.

SPEAKER_02:Yeah.

SPEAKER_05:So like I can remember down to the color of the hallway of the hospital, it was yellow. And the room was just like ugly mustard kind of yellow color.

SPEAKER_00:Hospitals.

SPEAKER_03:Yes, it was just this weird, and it was a weird hallway that was leading to nowhere but there. And it was like a dead end. And normally you come in the hospital and you're like, oh, there's like so many wines in here and all that was just one path on its own in that space. And I just remembered that that path I walked and I would make the right down the hallway and keep going until I got to the room. And it was just that yucky yellow color.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah. I know what you mean. My in my culture, in my family in particular, there's a big thing about not being a burden on, you know, your family members when you're ill or when you're getting older, and people in general are not good at talking about what's gonna happen when someone is dying, and just that whole end of life process is very somber. Um and for both my dad and my grandmother, they left in the wee hours in their sleep. That was just how it had to go, right? Nobody's around. And so now's the time. So yeah, I I get what you're saying. Maybe that was easier, right?

SPEAKER_03:It was. I and and and I honestly I don't think she even would wanted her friend to be there, but that's just really what happened. And I think she realized that her friend could take that better than we could. Um 'cause I don't really know what I would have been able to do if I'd been that person. And I honestly miss being there like that. Because something happened that held me back in class that did not get me there. Oh gosh. On time.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah.

SPEAKER_03:Literally. 'Cause I was on my like, and this is you know, obviously cell phones are now a bigger thing at in 2003. So I'm on my way and somebody for the house like at home is calling me and I'm like, why? And then I'm like and I was like, I know I should have rushed. I should have been there already. And I literally was like a few minutes away. Because I was one of the first to get there. I actually we all they said just come to the house first, and then we all like kind of bundled in the cars and went. Um and then I remember that hallway, like it was like you know, when it's like the twilight zone and you feel like the hallway just looks like it kind of zooms in and out. That's what it felt like walking down that hallway. Because I knew what I was walking to. I just had never lost anyone. So I that's that was my first experience with like with death in itself, too.

SPEAKER_04:So it was a lot.

SPEAKER_00:I could see it in my head, even though I haven't been there. I think it's just like for family members who's been through that experience, it's like those hospital scenes, right? Like it just just like based on your description of the colors and the hallway and how it turns. Like, I actually feel like I totally know what you're saying.

SPEAKER_03:I literally couldn't even watch, like, because I was a Grey's Anatomy fan, and that was like a big time for me watching Grey's Anatomy. I couldn't even watch it because I felt like it literally is right after that they started talking about cancer, like somebody had cancer in the show, and then I was like, No, and everything I turned to somebody had cancer and died, and cancer and died, and I was like, I just have to turn T T V off. I had to like everything had to go. It was it was crazy.

SPEAKER_00:How did you move forward from there?

SPEAKER_03:The way I do everything, I just pick up and keep going. It I didn't I didn't process it because uh nobody else was processing it either. But what the crazy part was is I'm the youngest, but I was the one I picked up my mom's dress and you know, I made sure that everything was okay before like, you know, the viewing and stuff like that. I even down to like they literally put some like I want to say whorish red lipstick on my mother. She liked red, she liked red on her nails, but like this lipstick they put on her, I was like, I can't even believe you put this here, and I literally wiped it off. Like I was like, I could like I can't let you have my mother look like this.

SPEAKER_00:They usually ask for a photo game.

SPEAKER_03:They do, but this person.

SPEAKER_00:But they just didn't pay attention. Ugh, that's all.

SPEAKER_03:It was just like it was the red was just like really too much. Like you can do the red, but not like uh I feel like she should have been like prostituting with that red that they put on her lip. And I was and I was never a red fan. Now I'm like, I I'm a signature red lip girl. And um, yeah, I mean, honestly, it did take me a long time to think about what had happened. Um but because of I I wanna say also my dad is uh West Indian, Caribbean, so they do not process these things, they don't talk about these things. So it was we're not talking about this, you're just gonna kind of move on from it. And I felt like even the family disappeared, and I once once it was just a week after, everything got so quiet that it was like, where did everyone go? All these people who showed up to supposedly show their love for my mom didn't even call the house to see how her children were doing. And I started to get angry about stuff like that. Um and I vowed I would never let somebody I love or I know go do that also. Um, so even later on, having other family that I knew, I was that one that I was like, Are you okay? Do you want to talk? I'm still here, I might not be there in physically, but like I know that it feels empty when that person is missing, you know? And it was like you had we just had to keep on going on with our lives, like like her room wasn't still there, you know, and that my dad didn't still sleep in that same room. And it was just like it was very awkward at times.

SPEAKER_00:What about your siblings? Did you talk to your siblings about it or they're the same as your dad?

SPEAKER_03:They were the same. Nobody talked about it. Like it was so weird and and still weird that no one still really talks about it. Like I made it a point that was my way to like really honor her, is to tell stories about her, even to people who didn't know her.

SPEAKER_04:Um and to even friends of mine, it's funny, like friends of mine that have known her, she was the cool mom.

SPEAKER_03:You know, we were the ones that were able to drink at beer in the house at like 17 and 18, and my friends are like, Are you gonna tell my mom? And then she's like, No, if you just drink it here and don't try to go home, you know, drunk, I'm fine, you know, that kind of thing. Or like literally She's the smart mom.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, because that's how she's gonna keep you guys out of trouble. He's drinking in parking. Yeah.

SPEAKER_03:But even like high school, um, it was funny because one of my friends, this he was one of these kids that like everybody knew, but he would after school um or during lunch or whatever it was, this is high school too. Like, he would go to my mom's car if she was coming to bring me lunch. He's like, Mom, can I have lunch next time? And she would bring him lunch. She would bring like six or seven other, like, she would bring enough McDonald's for seven other people. And my friends were like, Your mom is awesome. They would want to come home with me. Literally, people wanted to always be at our house. They're like, Your mom's so cool. And I'm like, you know what? It's you're right. And I knew what I had, and I knew what she was. I knew that she was that person that was a gem that you don't find often, you know. Even um just the things we did as kids, we played like literally manhunt with water guns in and out of our house, water on like hardwood floors, and it was just okay, we'll clean it up later. Yeah, okay, sure, mom, you know. And my dad would probably like he's having a fit because it's like, why are we having water guns in the house kind of thing? But she was just like, it's not that serious, it's just water.

SPEAKER_04:And she was right. It was just water, and we were having fun.

SPEAKER_03:She was the best, and I will never veer from saying that. And I've always said I wouldn't be a mom like her.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah. Thank you for sharing that. Because I I see what you describe about her and you. There's that kind of spunkiness, you know, that practical thinking, cut to the chase, um, being very realistic about what really matters. Yeah. Right? No BS type of wisdom.

SPEAKER_03:Absolutely. I remember a story, which is totally off topic, but I remember a story. My sister and I were out, we were waiting, it was like 5 a.m. She literally was at the door. My sister and I were turning the key, she was opening the door, and she this excuse my language, but she was like, Y'all lost your fucking minds, right? We was like, I couldn't I didn't even know what to say or do. Like, she literally like was at the door and opening it for us as we're trying to my key was stuck in the door. So she didn't wouldn't have mind if it was like 11, 12, 1, but it was five o'clock in the morning, so that's why she got upset. It wasn't anything else that it was that late. We had her her cell phone. We didn't use it to call her, so she got upset. So eight o'clock in the morning, she decided she was going to clean. So we had to get up and help clean at that time too. So that was a lesson learned. You got cell phone, you cell phone.

SPEAKER_00:It's a cool mom. Yeah. Yeah. So what what would you say to someone who may be going through something similar right now?

SPEAKER_03:You don't forget it will get easier, but it's never going to go away. Because like you see, that when I talk about her at times it just hits me. But I can talk about her and be happy as well, because I remember so many good things, and that's how you honor the person that you lost, um, is by telling their story and keeping their memory alive and not you know, like a lot of people say, like people lost their battle to cancer. She didn't lose. She went down fighting.

SPEAKER_04:And it also taught me that my voice matters too.

SPEAKER_05:Because if she didn't voice her opinion and tell people or the doctors that this is not okay and I don't feel okay, I think I'd have lost my mom a lot faster.

SPEAKER_04:And I wouldn't have learned how important it is to speak up for myself.

SPEAKER_03:Um Yeah, I would just kind of say that it doesn't necessarily get easier because I don't want to lie and I'm not gonna sugarcoat it, but being transparent, it there's a there are hard times. There are times when it's like when it comes around to the day that she passed. Um sometimes I don't want to get out of bed because I know or I don't want that day to come and go because then it's real still. But sometimes it's okay, but now dealing with my own having dealing with my own diagnosis of cancer, I have to remind myself that every day above ground is a day to be grateful. And she wouldn't want me to just wallow and not acknowledging her presence, you know. So I try to do what I can. Sometimes it's just doing something that I know she liked on that day, you know.

SPEAKER_00:That's lovely. I've never thought of that. I'm gonna do that now too.

SPEAKER_03:She was just a silly person, so like little things that like I knew I got my quirkiness from her. Like I knew that just even you sitting and watching old cartoons that which we used to do. Even just going or talking to her old friends. They would talk about old times that they had with her, or I just, you know, remembering the stories that she told and you know, playing songs that she likes. Even though some of them make me sad, there's sadness that just fills me.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, it's something that I've been thinking about, especially after I started this podcast and I talked to more people about their experience losing, you know, someone very close to them. And um my dad died in 2017, so it's gonna be four years this August. For my mom, it's like going to visit his site, and because I live farther away and sometimes the lands in the middle of the week, I end up just like not doing anything, and then the day just passes. I don't feel great about that because it kind of feels like you're forgetting the person, but they matter still, right? But I haven't but yeah, I haven't fully thought about like what is a ritual or something that I can do so that he's not forgotten. There's a weird kind of guilt or something um when I don't actually spend the time to really remember him. So I I love what you said about them. I'm gonna steal it.

SPEAKER_03:That's quite alright. I mean, there's a lot of times that I did have that guilt also because I wasn't able to process it properly to say what can I do that even though it might may make me sad, how am I still honoring this beautiful woman?

SPEAKER_00:Yeah. How do you think having gone through that experience with your mom impacted your own experience with cancer?

SPEAKER_03:I think it actually groomed me to be that person that knew that I needed to have a voice and to be able to say what I needed to and when something was wrong, or even if it was right, just to be able to acknowledge that. Um because as soon as I found my own lump, honestly, um, I knew something was wrong. Because I added all of the things that I had been feeling before that, that something was wrong. And I knew fatigue was a very big um part of cancer. But it was funny because I thought the fatigue prior to finding the lump was me just getting back in my groove of exercising that I was tired because I hadn't found the balance of sleep and working out, um, because I was running like three to four miles a day. Wow. And I thought it was just wearing myself down.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah. Yeah.

SPEAKER_03:And I was like, I'm just tired, I'm not eating properly. But I literally was to the point where I couldn't walk up the stairs without being like winded, but then I could run, but I didn't understand that. Like it just was not making sense. And that day that I got in the um bathroom and went to take off my sports bra, and I literally put my right hand like on my armpit, and I felt that lump and I said, wait a minute, that wasn't there before. I I I replay this in my head because I pushed it like this is not here, like this doesn't exist. Let me push that back in. And the more I really tried to not feel it or to manipulate my breasts, it pronounced itself even more. And I was like, how was I not how did I not feel this? Maybe the way that because I did have a larger breast. So um I said maybe that's why I didn't feel it. And that day I got in that shower right after, and it felt like like I was talking about that hallway. That time in the shower felt like it was an eternity. I don't know how long I was in there, but I'm sure it wasn't that long because I wasn't I had a time frame of when I needed to go where I was going. When I was finished with the shower, I just got up and went about my business, still knowing in my head when I get home, I still got business to take care of. And almost didn't go and do what I had to do, but I said, let me just go do this and come back and figure this out. And from there, it was like resource, resource. What can I find? Where can I go? Because I knew I was too young to really go get a mammogram. And I knew that I was going to have to call whatever numbers and look up whatever I can in order to find something. So uh it just was from I guess seeing so many doors slammed in my my mom's face that I knew that I was gonna get the same thing. Um, I just felt like as a black woman, I knew there was gonna be a struggle. It wasn't gonna I've never had anything just come to me easily. So I knew when this came around it was going to be a fight and um that I was gonna win because I wasn't going to be ignored, I wasn't going to feel like I was inferior because of like me not having insurance or because at the time I wasn't insured. You were going to give me the same that anyone else has. And if you don't, then I'm still going to keep pushing for it because I know that I deserve it. Don't get me wrong, I probably didn't get what I everyone else got, obviously, because I did see that I really saw the difference in what I was provided, and someone of a white kind of part was her um was provided because I had the same oncologist as another woman, and I we literally had the same path almost, and I was just like, something is not right here. I felt like the whole um dynamic was off completely, but I knew that I was still going to try to get as close to the best care as possible, you know, and that's all I could do.

SPEAKER_00:It's exhausting.

SPEAKER_03:It is its job.

SPEAKER_00:Cancer by itself is exhausting. I mean, you were basically, as you said, primed for that, you know, that you have to advocate for yourself to really get the care that you need and deserve. But it's just a whole nother layer of stress. Yes. Right, on top of a already a very stressful situation. How did people respond to you when you pushed?

SPEAKER_03:For the most part, um I did get a lot of resistance. I did. Because even coming down to um once I did get the you know, scripts for mammogram, sonogram, I called the doctor's office and And the woman that I called, well not the doctor's office, I called the imaging center and I got resistance on the phone. She's like, name, date of birth, and she's like, You're not old enough. And I was like, tell the lump in my breast and tell that to the doctor that just gave me the script. So are we gonna have this fight or are you just gonna make the appointment and you do your job and leave me be? Like, your job is to make the appointment, not to have this conversation with me. Um, and then I had resistance also because the GYN that I saw, she had already given me a number to a um surgical oncologist because from her feeling the lump, she was, I guess, sure that it was something as well as I was too. And I called and made the appointment, and the um, I guess his secretary or assistant, whatever she was at the time, said to me, Well, you don't know you have cancer yet. Do I need to wait until then? The appointment you're giving me is already a month out from here. Now, if I wait until that date when I'm going to get this, whether it's a yes or a no from the San Own Mamo, that's another month out of there from there. So that would be two more months away. Why am I gonna wait two months instead of you just making this appointment, make it tentative, and then if I don't need it, God bless me, because then I can get that canceled. How about that? And she felt really like you I can hear the quiver in her voice that she just was like, Did she just read me? And I'm like, Yes, I did, because you need to mind your business, make the appointment. I was already, you know, basically referred to him for a reason. And if I don't have cancer, even if I do, the lump still probably needed to be removed because it was big enough. It was literally the size of like one of those gumballs that you'd get out of the machine, like those little bouncy balls, like it's big enough that I felt it. You could literally have felt just rubbed past my breast and felt it at one point. Um, and I just was I I didn't understand why it was it was like it was as if she was the gatekeeper. And I didn't understand it. I was like, well, you know, nobody wants, I don't want this appointment. Can we understand this part? I don't want this, but I'm making it in case I need it so that I'm not pushed further back and that I'm not waiting because who wanted to wait another month to figure out what's going on? Because it literally took me from September to January, is when I actually got the miscectomy. So all of that in between was times of testing and biopsies and MRIs, literally months of it. It was it was a lot of fighting, and I didn't understand why I had to fight to prove to you that I needed the help that should be there. Why was there resistance? Why wasn't it that as a woman I'm telling you, and we just went through all the avenues and everything is in front of your face? It's like you've got the platter, but yet you're telling me, hmm, I don't know.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah. It's losing the forest for the trees. You know what I mean? It's like they just get stuck on checking the boxes and the dates and the criteria where it's like this is someone's life. Exactly. And there are other things at play that they're balancing. Um, so I I don't know. It it's unfortunate that I think a lot of times in the medical field that's just the case for a lot of the people you have to interact with all along the medical process because they're generally large bureaucracy, so they have these very specialized people who just handles a very small part of the whole process. And yeah, they don't see the forest at all. And to them, they're doing a good job. Yeah, right? They're doing their job.

SPEAKER_03:It's like, no, there's a bigger picture that you're missing.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah.

SPEAKER_03:You know?

SPEAKER_00:Yes. Do you think when you have those types of conversations with people, do you think it actually it actually registers in their mind? Absolutely not. I'm laughing because you're shaking your head. Because I guess my my question is we talk about sort of the racial disparities in terms of patient care across, you know, not just cancer, but all types of illnesses and diseases, chronic conditions. And while I would like to think that it's important, obviously, to have your voice and being an advocate for yourself and getting what you need, I like to romanticize and think that that somehow can also get people to see the bigger picture and also like how they're kind of contributing to that process. So in your experience, like, did anyone sort of come across and say, Oh crap?

SPEAKER_03:Have that aha moment? Yeah, like like I was kind of being a jerk and I was I had no one that admitted that basically that they were standing in the way and and you were just looked at as like a difficult patient, basically. Yeah, I was I was that combative woman that like, oh, here comes the angry black woman again, and I really was that person because it was I um and I didn't care. Because, you know, for the first time in my life, I was okay with being that angry black woman because you were gonna give me what I just what I needed to get done. And there's no way that, and not to mention, like, there's no way that I could have proved that if you didn't you're standing in my way from me getting what I need to, and this causes me my life. Am I gonna be here to argue that with you? No. So I'm gonna keep on pushing, and you're gonna stand there, or I might have to push you over and go to the next person. I've learned that I had to do that too. I figured out even when I had certain doctors that I spoke to just were very lackadaisical, and I'm like, this is my life. What are you doing? Like, do you not see me here? Like, do you not see me? And that I think is also what it was. They did not see me. A lot of them just saw, like, okay, this is just a tumor here, or this is like it was so technical that I was just like, there's a person, I'm not a piece of meat, like I'm a person. There's like even when it went came down to the mastectomy, I felt like my surgical oncologist was so worried about the breast. And I'm like, but are you forgetting that I'm also telling you, and I'm this is also a woman um who is in the childbearing age, who you know, I'm I have large breasts, so it was you lose the breast, it's gonna I'm you're gonna lose your nipple. And I'm thinking, then I'll never breastfeed, I'll never all these things are like floating through my mind, because even when I'm talking to him and we're discussing what my options are, I said to him, and I stopped real quickly, and I said, So if this was your mother or your aunt or your grandmother or your sister or your girlfriend or fiance, what would you tell them to do? And he told me that wasn't fair, and I think that's the first time that he realized that I was a person I could be his sister or his somebody he knew, that he put that attachment there, and I think in the medical field they try to detach themselves from that because they don't want that emotion to take away what they can medically do for you, and I understand that, but then they also have to have in I think in the oncology field in itself more empathy. You have to have that little bit more empathy than the other average doctor, just because you know that this is dealing with someone's livelihood. They could this could make or break my life. It could be me being here next year or not, or next month, and not, because we don't know how aggressive this is. So it did it did take a while. There were a couple of doctors that I want to say that, and I I honestly want to say the doctors that I probably felt like that saw me were people of color. So my um plastic surgeon, I feel like he saw me. He is Filipino, and we were okay. So that I was like, we are cool, we're good because we both understand that there's a lot of stuff that goes on that's not okay. And we would even have discussions about it, and you know, just even a lot of the charity work that he did. I think it's a smiles project that they do where they do the cleft palettes. He goes every year and does it yes, he does that every year, and I'm like, that's why I love you. I'm like, it like the fact that you that's your vacation every year. Like, you don't even really go on vacation, you go and you do this. I think he does it twice a year, to be honest. Um, he'll do he does it in the the um like the Christmas time or around that January season, and then he does it again in the summer because I know I had another surgery that I had to postpone because of that, also. But he saw me, and then I picked specifically my radiation oncologist because she was a black woman, and I was like, there's no way that she doesn't see me. Because even when she spoke about um how my breast is gonna change during radiation, she's like, it's not gonna be pink because we are not pink people. Your breast is gonna turn black, it's gonna look really charcoal, and that's exactly what it looked like. She was very honest, she was very like that was just her personality. She was like, I'm telling you how it is, how it's gonna be, and this is what it is. But she was also that she also had that soft side because if she saw me get to the point where I was giving up, she knew that it was like, listen, I know we both black women and we're supposed to be strong, and this is what we're supposed to be, but you're going through something. So you're allowed to cry, you're allowed to be upset, you're allowed to feel. And I might not be that like sentimental type of person all the time, but I feel you and I see you.

SPEAKER_01:Yeah.

SPEAKER_03:And even just telling her that telling me that she saw me was like, I felt like a whole person then. I didn't feel like just a piece of me that you were just treating that one piece. She tried to connect me with another patient of hers that we were both on a similar path. And I was like, you that right there showed that you were trying to see me as more than just another patient that you saw and that came and went.

SPEAKER_00:Yeah, and thank you for explaining that what you mean by seeing. Yeah. And as we were talking, you know, starting with your mom's story and then to your own. I can see the sadness and some of the issues that you're probably still working through. But I can see exactly what you said. It's like that experience really prepared you. So like as you are talking about your own journey, it's strong. Like your voice is there, you know what you want, and the whole mood changed. I think it's very evident in how in walking through that with your mom, I think it strengthened you. And you've really been able to advocate for yourself. Is there anything else you wanna share before we wrap?

SPEAKER_03:I guess I would just say um we all have a voice and no one's is bigger than anyone else's. It really just depends on um who's listening to it. Because I could have the smallest platform and I don't have a huge platform. But I've had women that even men, um, that I don't even know just peep in my inbox and say, Thank you. And I'm like, for what? I don't even know like what am I doing that you're saying think thank you for, but I'm just speaking my mind and I feel like there's people that are hearing it. And um at one point in my journey, um I hate that word journey, one point during my um cancer story, um I wouldn't have been that person. There was a time when I felt like I I was defeated. I felt like through all the fighting I didn't know how to fight anymore. I had to push through it, and like I told you, I push through things, um, push through it in order to get to the point where I can say that I do still have to fight, sadly, even though I'm on the other side side the other side of cancer. Um and I don't think that there should be a fight. I think that that's one of the things we need to to normalize that fighting is not what should happen. There should be I don't want to say a walk in the park, but it shouldn't be hard either. It shouldn't be where you're struggling to get what you need and to get your needs met or to even feel like this is a job being on the sh the phone with insurance company or a doctor's office. It it just feels like even doctors are they're being overwhelmed. And it's sadly the people who are being punished are the patients because the healthcare systems are becoming companies and then the doctors have more patients, and the patients are sitting there like, Well, I don't have the time to talk or even tell you. And if I have chemobrain, I don't remember sometimes, even if I wrote it down, I can look at the question and have asked you the question and still forgot what you said. Like there's you know, it it's just we just n need to be able to allow people to be people and human and it not to be such a company and organization. The the humanity needs to come back into the health system, and I think that's where we even get rid of all these health disparities, is when there's more human contact and more human interaction, and it's not this big conglomerate that's coming down and it's like you don't even see me as a person, I'm a number.

SPEAKER_00:Right.

SPEAKER_03:And I'm nobody's number.

SPEAKER_00:As a follower of yours on social media, I'll just say that you keep it real, which I think is what people really appreciate about you, and that's how you know I think who your mom was as a fabulous person continues to live on through you. So thank you for sharing her voice, your voice on your platform. Where can people find you online?

SPEAKER_03:I am on Instagram. My tag is B R Sugar, but it's B-R-S-U-G-A. There's no R on it, but um it's meant because I'm sweet. Um and I am also a ambassador for an organization called for the Breast of Us, where we are educators of um breast cancer resources, and just for women of color, just to be able to know that you have a voice and that there are resources out there for us everywhere. And they have created resources so that no matter what state you're in, there's somebody there that can help you find the things that you need in order to make sure that you're not just somebody's number.

SPEAKER_00:Well, thank you so much for taking the time to chat with me today. It was very nice to hear more of your story.

SPEAKER_03:Thank you.

SPEAKER_00:After our recording, I thought a lot about Shani's experience with the receptionist at the oncologist's office. It's the kind of experience that is so familiar to those of us who have had to navigate the healthcare system to get care for complex medical conditions. But it is even more stressful when you know that by speaking up, you will be labeled and dismissed with a negative stereotype, like the angry black woman. These kinds of stressors, even if seemingly minor in isolation, add up over time. And not just in healthcare, but across all kinds of important areas in life, such as education, work, and housing. It is therefore not surprising that many minority groups have less positive health outcomes. Living with cancer is completely overwhelming as it is, so some days you just may not have the energy to get over the extra hurdle thrown at you. But that sometimes can make all the difference in your trajectory. A big shout out to Shoni for bringing to life what we read about in research papers and textbooks. You're not just a number, and we thank you for helping us see you. And that's a wrap for today. Please follow the podcast if you will like to hear more stories from Cancer Thrivers, caregivers, and family members. I would really appreciate it if you can leave an honest rating and review in Apple Podcasts or Podchaser so I know if I'm serving the interests and needs of you listeners out there. You can also share any feedback and suggestions directly to me by visiting talkabout cancer podcast.com. Thank you for listening.