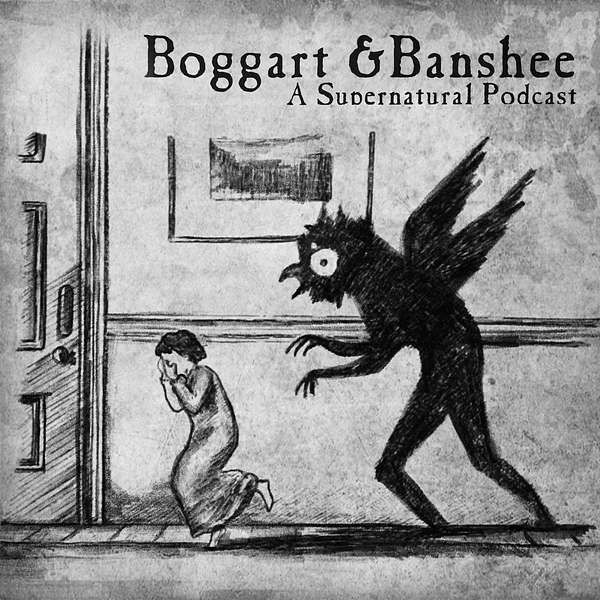

Boggart and Banshee: A Supernatural Podcast

So a Brit and a Yank walk into a supernatural podcast… Nattering on fairies, folklore, ghosts and the impossible ensues. Cross your fingers, turn your pockets inside out and join Simon and Chris as they talk weird history, Fortean mysteries, and things that go bump in the night.

Boggart and Banshee: A Supernatural Podcast

The Green Children of Woolpit: Fairies or Foreigners?

The Green Children of Woolpit: Fairies or Foreigners? Simon and Chris celebrate the new and definitive book by John Clark on the Green Children of Woolpit: two children with ‘leek-green’ skin who, in the middle of the twelfth century, said that they came from a twilight place called ‘St Martin’s Land’. They wore strange clothes of an unknown fabric and spoke a language none could understand. Strangest of all, they ate only beans. Had they strayed from fairyland into Suffolk or were they lost, starving children orphaned by tragedy? Simon and Chris try to sort out some of the curious details of this very curious story and also bicker about Jinn, weird birds, kosher food and Excel spreadsheets.

*John Clark, The Green Children of Woolpit: Chronicles, Fairies and Facts in Medieval England (Exeter New Approaches to Legend, Folklore and Popular Belief, 2024)

[Simon] Chris, the rumour is that you've been bird watching this week.

[Chris] Yeah, we had a whole bunch of snow and so we just fill up the bird feeder in front of the house and I sit and watch bird TV. So it really is fun but I saw this one bird that in shape it's like a cardinal but it's all mottled feathers and weird colours and I thought is that bird sick? What's going on with it? Because it was just so eccentric looking with its plumage and then I looked it up and it's actually something kind of rare called a leucistic cardinal which just means that they have white patches or they have different coloured patches. Apparently you can even get a yellow cardinal if you're really lucky but normally they're just bright red birds and this one's all mottled looking so I'm hoping to snap a picture of it because it is so rare.

[Simon] So it's not a different species, it's a little bit like say having an albino bird?

[Chris] Right, yes it is.

[Simon] Interesting, I've never come across that and I suppose with this vision of different colours we come to today's subject rather neatly and this is of course the green children. This summer a colleague of ours, John Clarke, brought out after many many years work his wonderful The Green Children of Woolpit Chronicles Fairies and Facts in Medieval England and we thought we would wade in. So Chris what could you give us as background on this story?

[Chris] Well this is a narrative written by Ralph of Coggeshall, monastic, he was a Cistercian and he wrote an account called Concerning a Boy and a Girl Who Emerged from the Ground. Another wonder, also not unlike the previous one because he was he was telling wonder stories in his chronicle, happened in Suffolk at St. Mary of the Wolf Pits. A boy was found with his sister by the inhabitants of that place near the mouth of a certain pit that is situated there. In the shape of their whole bodies they were like other people but they differed in the colour of their skin from all the mortal inhabitants of our world for the whole surface of their skin was dyed with the green colour. No one could understand their speech. Asked how she and the boy had come into this land she replied that when they were following the cattle they had come into a certain cavern. When they entered it they heard a beautiful sound of bells. Captivated by the sweetness of the sound they've gone on wandering through the cavern for a very long time till they reached the way out of it. When they came out from there they were stunned and struck senseless as it were by the brightness of the sun and the unusual warmth of the air and for a long time they lay at mouth of the cave. Then they were terrified by the noise of people coming towards them and tried to flee but they could in no way find the entrance to the cave before they were caught.

[Simon] Yes and this is one of two sources that describe this extraordinary event that to the best of our knowledge took place sometime in the middle of the 12th century and it's unusually detailed and it's also well within living memory. These accounts seem to have been written down within say about 50 years of the event in question and one of the two authors who actually goes into details Ralph of Coggeshall who you have just quoted from actually lived very close to this part of Suffolk.

[Chris] Who's the other source?

[Simon] Well the other source is a gentleman called William of Newburgh so these are both of the monastic writers and in fact an earlier generation of Fortean writers were very excited about this case because they often said oh my goodness look we have two different sources two different accounts about the same event it must be true and one of the things that John Clark has managed to do I think very effectively in his new book is show that actually these two writers were almost certainly relying on a previous source and I would say that there is a 90% chance that a missing source existed and they were both taking inspiration from this source and John suggests and I think here maybe there's a 50% chance that the missing source is actually by one of these two writers Ralph of Cogshill it was if you like an earlier draft but maybe the thing that's really worth drawing out isn't that we have two sources it is that Ralph of Cogshill he was born shortly afterwards and he was plugged into local rumour networks he knew some of the people who are in the story.

[Chris] Now William of Newburgh we met him in our episode on the walking dead of Byland Abbey didn't we?

[Simon] That's right so he comes from very close to Byland Abbey I think it's even just two or three miles away and this is something that's interesting about these writers in the 12th but above all I think the 13th century chroniclers couldn't resist including what we think of as anomalous or strange stories and so hearing about green children coming out of the ground was just catnip to writers like this that there was no way that they were going to pass over it.

[Chris] Well I can see why this was one of the earliest Fordian stories I ever came across and I was just enchanted by it.

[Simon] I had exactly the same experience when I was in my teens and I first read about it and I just didn't know what to make of this and I had no idea that here I am almost 40 years later with John's massive 300 page book on my knee.

[Chris] The child is father to the man.

[Simon] A very good way of summarising the folklore around this is as John does in one of his subtitles where he says foreigners or fairies. Either we have a couple of fairies who have accidentally strayed into our world or these are a couple of kids who have got lost being separated from their parents and their communities they don't seem to have spoken English they spoke another language that was unidentified and I'll just immediately give you my take on this. These were foreigners who were understood to be fairies by the locals they were from some foreign community that somehow had ended up in the middle of the Suffolk countryside and yet it's very clear from the way that they were written about and the colour of their skin didn't help in this respect that locals actually believed they came from the fairy world and we'll come to some of the details about this later. I mean what would be your take on this Chris?

[Chris] Well I was intrigued by John's talking about the clothes that they wore. No one recognised the fabric or the style that they were wearing and he makes a case or someone has made a case also that they were the children of Flemish weavers or wool merchants because the Flemish community had a real style and flair for the way they dyed textiles. Now what I don't understand is why the children's language was not recognised. This was an area where there were pilgrims coming through to buries and Edmonds and various monasteries and things even if you had Flemish merchants or dyers or weavers coming through somebody would at least know maybe they didn't speak it but they would say oh yes that's actually that's where they're from. I don't speak Russian but I can recognise Russian when I hear it. It's also been suggested that they were Jewish. I would think that even these people would have understood okay they're speaking Hebrew or they're speaking German or they're speaking French. It just doesn't play that they didn't recognise the language. That's something that I'm very puzzled about.

[Simon] I suppose that we're a little bit spoiled today that we hear many different languages all the time not least with the internet. This was the 12th century they were in the middle of the countryside. I do acknowledge though that they were on a very busy road. I like your point that you would have thought that sooner or later someone was passing through who spoke a language where the kids recognised and actually for me this is one of the reasons why I would pretty much rule out Flemish because I think that Britain had a lot of contact with Flanders in this period. The languages are not actually the most different languages in the world anyway. You would have expected that there would be a certain number of words in common except your general point but I think if anything that's a reason to probably rule out Flemish. These kids my suspicion is they came from somewhere further afield somewhere a bit more exotic and maybe the unusual nature of their clothes also points to that. I mean the other question that comes up is about the food that they were eating or rather the food that they weren't eating.

[Chris] Right there's a passage where they're basically refusing all food and when the girl finally learns to speak English she says we thought this food was inedible that you were offering us and I'm not sure of what the actual Latin term was whether it was inedible or untouchable or something like that because it has been suggested that they were Jewish and they were worried that wasn't kosher. What's fascinating though is they finally found that they could eat beans and they just fell upon the beans and ate them for months.

[Simon] And this is where Chris if you don't mind I'll just read the passage because I think a lot of these accounts that have come down to us are shaky there's remembering and misremembering but I think when you get to this you might actually have a moment from very early on in their let's call it captivity in their adoption in this new community. At last when some beans newly cut with their stalks on were carried into the house they made signs with great eagerness that some of the beans should be given to them. When the beans were brought they opened the stalks not the bean pods thinking the beans were contained in the hollow of the stalks but when they didn't find beans in the stalks they began to cry again. When the bystanders noticed this they opened the pods and showed them the naked beans and once they were shown them they ate them with great joy and would touch no other food at all for a long time. So these kids had been starving and at a certain point they see beans and they're very happy to see them and they beg to actually have them there seems to be some confusion about where the beans are on the parts of the kids and then they they launch and thanks to the beans they actually survive because it sounds as if otherwise they would have starved they were just refusing all food.

[Chris] If this was a true story what kind of a plant has beans in its stalk that they thought they were looking at? When I look at these kind of beans that they were supposedly eating the stalk looks like rhubarb but I don't know of any plants where the the beans actually are found in the stalks.

[Simon] I can't think of anything there either. I wonder whether they had not been eating this food out in the fields when they were actually found. The children are supposed to have come out of some kind of hole or bank in the ground and my guess would be that they were separated from their parents they were starving they'd found some food in the field namely these beans and that maybe when they heard people coming they ran as they thought for refuge in some hollow or some place where they were actually harried out by the locals and I wonder if they didn't already know the beans for this reason that they'd been eating them in the fields for a couple of weeks before this would explain why they were so enthusiastic when they saw the beans brought in but as you've just pointed out it doesn't explain that aspect there because if they really have been chomping on them in the fields then they would certainly have known where the beans were.

[Chris] Right exactly yeah.

[Simon] So quite what you can do with that I'm not sure but with language with clothes with the the beans with food we have this sense of people who just don't belong in this community and are very different and this is before we even get on to the greenness of their skin but let's leave that delight for a little bit. Okay. Maybe we can move on from there to the question of where the children or better where the young woman says that they were from.

[Chris] Apparently there are some differences between William and Ralph as to where she says they came from. Some say in a pit some say through a cave came through a passage and into the light and the sun and it was it struck them senseless because it was so hot and so much light. She claimed that they came from a twilight country where the sun never rose although apparently that was a question that was asked her. Seems as though she was asked a leading question does the sun rise in your country and I'm like what kind of question is that? Who would ask that? Who would ask that question? But in any case she says it was it was sort of a twilight country and they were herding their father's cattle and they strayed down this passage like a tunnel of some sort and then came out into this different world.

[Simon] And there were bells out there in the middle they're described a little bit differently in the two accounts but when they were in this cavern let's say or this corridor they seem to have been confused or lured by the sound of bells.

[Chris] Yes captivated by the sweetness of the sound they followed the bells until they reached a way out of it and then they couldn't find the way back. So that's one of those sort of folkloric fairy tale stories of coming out into a place and then not being able to find your way back.

[Simon] And we get this a lot with the Green Children's story that there seem to be various legends that we associate with humans going to fairyland that have actually been turned on their head here where it seems to be that these two children who the locals believed were fairies had come out of that fairyland and it's as if the story has been turned on its head.

[Chris] Yes exactly.

[Simon] So instead of the human going into the cavern and walking for 10 miles and eventually coming out into this mysterious land you have the children from fairyland coming out into our mysterious world.

[Chris] Right and not being able to find their way back and maybe afraid to eat our food because then they can't return.

[Simon] So much in this story can be processed as humans using their own knowledge about fairyland and imagining how fairies would find themselves in our world if they accidentally got stranded here. I mean another point that is curious about their own world is that they say that it was Saint Martin's land. Did you make anything of that? Very suggestive.

[Chris] I don't know what to make of that. I mean I've seen the the comments that Saint Martin is the patron of children in Flanders and Saint Martin there's a a village not too far from Woolpit that's it's got a prefix on its name something Saint Martin's and maybe they came from there. So honestly I don't know quite what to make of that.

[Simon] It gives you a sense of just how confusing the sources are that it's been suggested that the nearby village of Saint Martin was actually really their home and they spoke a slightly different dialect there and so when these two kids turned up everyone said oh my god what are these very strange foreigners and I understand that English dialects were much more extreme 800-900 years ago but I think this is a little bit difficult to take. Yes. And yet what does seem to be communicated to us is that they arguably came from a Christian land because they seem to recognise Saint Martin they talk about there being churches in their land.

[Chris] Right which reminds me of like the Icelandic churches for elves they're supposedly a Christian people.

[Simon] And this is something that's always a point of tension of course in fairy tales this question of whether fairies can actually follow the one true god and be Christians and even eventually get salvation. And this is mirrored of course in jinn tradition in Islam where instead in Islam there's a very clear answer that jinn can be saved, that they can line up behind the prophet and enjoy final salvation whereas of course in Christianity that's left let's say artfully vague but whenever you get to the theology of it the answer is you've got to be kidding me. Whereas at the popular level there seems to have been this idea no no the fairies because they're not all good or all bad they're like us and therefore there is the possibility come doomsday that they too will be among the saved.

[Chris] Something else that I'm interested in reading the account of how there's not much sun in the world this is echoed in so many other stories. Gerald of Wales told of Elodurus also known as what Aladir he ran away from school and was taken into a cave and it was a most beautiful country but obscure and not illuminated with the full light of the sun. The days were all overcast as if by clouds and the nights were pitch black for there was no moon nor stars. There's other stories, King Hurla's stories, they're in the cave and everything's magically lit up by lamps but until they get there it's very very dark. So subterranean lands are obviously they're going to be dark.

[Simon] Or at least not as well lit. Right. For me this is one of the lessons of John's book. Clearly this is a reference to Fairyland. We don't have to go the whole hog and say these two kids fell out of Fairyland but we have to say I think two other things. First of all that the locals around Woolpit were convinced they were and second by the time that the girl spoke enough English to actually be able to communicate her story she had in some way taken on and absorbed this tale of their own early youth and it's rather melancholy in that sense that these kids own true story is lost and you have this fairy version of the world imposed.

But this business of low lights, Chris, you're absolutely right. It conforms to the idea of what the fairy world looks like and the antipodes that you get in many accounts about the fairy world. The idea that the fairy world is somehow the inverse of our own universe. I should also just throw in there that for me the most unintentionally humorous part of this story is when they describe coming out of the cave and finding themselves in this very bright and hot land and it makes Suffolk sound like the tropics and believe me as someone who went to university near there it's one of the coldest places in a very cold island so you know thank God we don't live in fairyland because we would all have five or six layers and scarves on. I suppose there's one other suggestive bit in the description of this world that they came from and that is the notion that in their world across a river if I remember correctly they could see another brighter land.

[Chris] This is very very common in the underworld stories. It's divided from the earth by a river like the river Styx. It's also found a lot in medieval accounts of what we might call near death experiences. The narrator sees a vision of the other world where heaven and hell or heaven and hell and purgatory are divided by a river. So it's just a really really common motif. Another feature is that it's reached by going through a rock or into a cave or an underground tunnel. You have to go either bodily through a piece of rock somehow miraculously to get to the underworld.

[Simon] In a way, it is a very melancholy story, because when the young woman grew up and was telling interested parties about where she came from, she clearly just absorbed this more general idea in English society of the time. I suspect there is nothing of her actual past in the story, and very probably she'd forgotten what her actual past was. I mean, how old were these kids? Maybe six?

[Chris] Or maybe older. I wonder, I don't know if we can say forgetting. If something really traumatic happened, where they saw their parents killed or something like that, or their village burned, they're not going to forget that. But that's not palatable to the audience. So let's go with the fairy story. You know, that's how we can continue to live.

[Simon] This brings us, of course, to the one thing that absolutely and emphatically does not make sense, and that is the question of the colour of their skin. Chris, over to you. Where do we even begin with this?

[Chris] Well, I actually did a spreadsheet, an Excel spreadsheet, about fairy colours, both in skin and clothing. It's not complete yet.

[Simon] It's not complete yet? We'll get back in a decade. Can I ask how many columns there are? How many different shades?

[Chris] Oh gosh, I haven't, I would have to have it in front of me to actually give you the detail. I'll send it to you or something.

[Simon] But it's substantial?

[Chris] It's substantial, very substantial, and I've just scratched the surface, really. But green-skinned fairies seem very rare. I mean, we've got John Walsh, who was a, what, a Devonshire cunning man, and he said that there are three kinds of fairies. There's white, and green, and black, and the black fairies are the worst. But I find them to be really relatively rare in the stories. They wear green, but the green skin just doesn't appear that much.

[Simon] Let's make that really important distinction, though. Green does seem to have been, and to some extent to be, a fairy colour, but it's their clothing, not their skin, and not their hair.

[Chris] Right.

[Simon] So, back to you.

[Chris] And I would emphasise that a lot of the green stories, so the green clothing, it's later. It's maybe Shakespeare and beyond.

[Simon] I'm a little bit sceptical about that, because you do have the Green Knight, Gawain and the Green Knight, so you do have this idea of green being connected to the supernatural, to otherworldly fairy figures. Perhaps we just don't have enough evidence to go in strong, whereas on the basis of our later folklore, fairy clothes are frequently, almost automatically green in a British context.

[Chris] Right, absolutely, and people are told not to wear green clothing. Humans are told not to wear green, because the fairies will not be happy about that.

[Simon] It's their colour.

[Chris] It's their colour. So, I was trying to think of, you know, when I think of these green children, I think of the colour of Kermit the Frog, or Shrek, or Princess Fiona. Priscinus is the word that Ralph uses. It's a sort of a leek green. It's sort of a darker green. And I'm sure that somebody somewhere has suggested that the green children were painted with some sort of greenish shade of woad, like the early Britons described by Julius Caesar. But it's also been suggested that the children suffered from chlorosis, which was the green sickness, or the disease of lovesick maidens, which is an iron deficiency anemia. This can also be called, there's a different variety that called favism. Fava beans contain compounds that break down red blood cells, and you can get anemia after eating too much of them, or maybe inhaling the pollen. And this is mostly for some people who have a certain genetic proclivity that would cause them to get anemia after eating these beans. Now this causes pale green skin. Pallor is a feature of favism, and it's also more common in men than women, which might explain why the little boy was sicker. But the trouble with chlorosis and favism are that the skin seems to be generally a pale green, not a leek green. So I have a personal theory. I would speculate about copper. Copper ingested, inhaled, or worn stains the skin green. Now there's no copper mining in the area. This is all chalk pits and things. I think flint mining is the only mining going on. But about 30 miles away, Rendlesham was a center of copper smelting, particularly in the 5th through the 8th century, with some carry over into the 11th. And I would think that there, even then, there would be small copper smelters working. So that's a theory. I'm also reminded at random that at Pendle Hill in Lancashire, nowhere close, fairies revealed to some mortals where copper could be found. And the fairies were also associated with copper mining in Cumberland and North Yorkshire. So they had some link to it, but that's just a theory. One point I find interesting is if you were trying to describe somebody of another ethnicity, if these were really foreigners, you might call their skin black or brown or red or yellow, you wouldn't call them green.

[Simon] Yeah, on that point of ethnicity, if I had read this account very quickly, I would just have assumed that these were people who were ethnically different. And of course, this fits in with the question of their language, the question of their clothing, the question of unusual dietary habits. So it all makes sense. The problem is, here, our two authors are emphatic, the greenness went away. Now, if green was just, let's say, a misconstrual by some English peasants of people who had slightly, let's say, olive skin from the Mediterranean or further afield, you would not expect the green to just go away with time. And yet it did, it disappeared. And at that point, Ralph suggests that this is a question of their diet changing, and it's not impossible, but in any case, it's not ethnicity. We have to rule that out.

[Chris] Right, right. Medically, if you increase the iron in someone's anemic diet, they lose the green tint. Apparently, there was one case of bad anemia in a redheaded young lady, and she was bright green. And they said, oh, yeah, we started transfusing some iron and she lost her colour in a few hours. So, changing diet may have done the trick.

[Simon] So let's just play through the implications of this. Son and daughter are travelling with dad, let's say. Something catastrophic happens. They're separated from their father. Their father is killed. In any case, the father leaves the picture. And these two, perhaps quite young kids, find themselves in the middle of the English countryside. Would we imagine that perhaps their diet was already not great, and that then they survived for two or three weeks without being noticed, and that iron deficiency started to kick in? Is this the kind of background story we could think of as being preferable to corridors in solid stone and lands where the sun doesn't shine?

[Chris] Well, we know that even children who grow up in poverty have had a greenish tint to them because of anemia. There's reports from, you know, council workers in Victorian times, for example, talking about this greenish skin. So it's possible they were starving and that lent the green to their skin. But that's a pale green.

[Simon] Yeah, and I think that if John were here, this is the thing that he would bang his fist on the table for. It doesn't say a pale green in the Latin. In Ralph, it's this word prazinus that you mentioned before, which suggests a darker shade of green. And it's awkward. And from what I can see, John, in the end, in the best possible way, has just thrown up his hands and said, I can't quite make sense of this.

[Chris] That's my theory about the copper, because you ingest it or you inhale it. Your father's a copper smelter. And eventually it wears off because you're away from that environment and you're eating different food and maybe you're better nourished than you were there.

[Simon] Going back to my point about foreigners or fairies in my formula, these were foreigners. They were understood to be fairies. If you understood the kids to be fairies because you happened to find them in a little hollow in the ground and everything else was understood in that way, maybe even quite a light impression of an olive tinge to their skin and extreme whiteness in their skin, something like this could have slowly through the years been remembered as no, no, they were dark green when they came out of the ground. I think that because people were looking at these kids through these filters of fairy lore, this is a real possibility. And of course, our writers tell us that the green disappeared. This means that this was an aspect of them that no one could go back and check on later.

[Chris] Right, right, exactly.

[Simon] We've had this fun time looking at this case, but surely now we need to step back a little bit and acknowledge that there are other cases of supernatural beings straying into this world, or supposedly supernatural beings, and effectively being caught or adopted by their human neighbours. Do you have any of these, any examples that you can give us here?

[Chris] Well, not necessarily green, but I think Ralph talks about the wild man of Orford, who was like a merman, and he also had strange dietary habits. I think they gave him fish and he would like squeeze the juice out of them and eat the juice only. Very odd. And he eventually, I think, escaped.

[Simon] He escaped back to the sea. My theory there is that he was an early carnival show turn, and he will have been taken around to different fairs, as was absolutely normal in later centuries. And this is just them exoticising some poor soul who was put into this role, and at a certain point he disappeared.

[Chris] Hmm, okay. That wouldn't have been my theory, but that's okay.

[Simon] Oh, no, no. I want to hear your theory.

[Chris] There's certainly plenty of wild men I've read about, but most of my examples come from the 19th century, where we've got, perhaps, shell-shocked soldiers from the Civil War running off and living naked in the woods. So it doesn't really cover the facts of this particular case.

[Simon] I think you've also, in North America, got more impressive wilderness. It's true that in the 19th century in the UK you do have people who go into the woods and live there, and they start to be, to use that dreadful verb, othered. But... Yeah, okay, sorry, sorry. I withdraw, I withdraw. Chris, tell us about other supernatural beings, and let's have an argument about those.

[Chris] Well, there are mermaids that get caught, and I can't think of a particular specific example. Again, they usually escape, so I never know whether those are, oh yeah, sure, sure, I caught a mermaid, but hey, she got away, so I can't show her to you, that kind of thing. When I think of green entities, of course, I think of the green ghosts, and the castles of Scotland just are crawling with green ladies. Most of them have very tragic and legendary backstories, and they usually just appear in folklore collections. You don't see a lot of people actually seeing them. Although, apparently, I was looking at the paranormal database, and there's a phantom green lady who crosses the road at Bread and Cheese Hill in Essex, and they drive off the road to miss her. And then, let's see, St. Nicholas Church in Curdworth, West Midlands, a woman wearing a green dress is said to search the graveyard for the remains of her royalist husband. So, that's the kind of ladies wearing green dresses. There might be banshees, there might be fairies.

There was that Yorkshire story about the little girl who went crying to her mother and said that there was a little man in a green coat in the parlor. The green man will have me. There's Green Jean at the, let's see, it's Weems Castle. She was a tall lady clad in a long gown of green that swished as she walked. Nobody knew her history, but she was, she hung around the castle. So, yeah, lots of green ladies. That's about the best I can do for green entities. How about you?

[Simon] Well, I can't compete. I was just thinking of how few green ghosts I know from England and I was very impressed by the Bread and Cheese Hill example. Also, we do have a couple of fairy cases where perhaps green just isn't that unusual, but there is one case from the Fairy Census 1. I think it's from Lancashire where there is a green boy and a green girl and they're described as actually being green, but I think really green has passed out of favour as a supernatural colour. This would be my guess and this perhaps leads us back to our argument from before, slight as it was, about whether green was a fairy colour in the Middle Ages or whether that's a later development.

[Chris] But who's the green ghost in Ghostbusters? That's a modern one.

[Simon] Okay, okay, so that works too. Good, good. I'd love to see an Excel sheet of ghost colours because...

[Chris] Oh no, don't get me started.

[Simon] You're barely going to finish the fairy one and I'll give you another decade's worth, but can you imagine the monotony of that Excel sheet? I mean, wouldn't it all be grey, white, black? I think you would have very few greens or reds.

[Chris] No, there's red ladies and red men, the red man that appeared in Napoleon. So yeah, there is more maybe variety in other supernatural areas, but yeah, the fairies mostly dress in green, but there's red, there's brown.

[Simon] I mean, just trying to start to wind this conversation down now, my guess would be that these were malnourished kids who looked very pale and right from the beginning they were seen through the filter of, oh my god, these are fairies. Their green, in inverted commas, left them and later on people misremembered just how green they had been. This would be my guess, however, I must acknowledge it's our sources emphatic that they were green.

[Chris] Right, although is it really possible that either William or Ralph met the children? They don't say that they did, so they perhaps were not actual eyewitnesses, but they went to the trouble of rounding up lots of people who supposedly had seen them.

[Simon] I mean, I think William, it's almost certain that he never came close to seeing the green children. Ralph, though, is much more interesting. I mean, Ralph is really from just down the road and he actually says in his account that we have heard from the family that took the children in. I think the Latin verb is or audivimus we heard, we were used to hearing about this account and that there we can be really quite excited that we have someone who isn't a first-hand witness but is a second-hand witness. Right. And by the standards of the Middle Ages, second-hand witnesses are good. We should take that with a hearty clap on the back. We don't know when Ralph was born, but if these events took place, and I think there's good reason for thinking this in the very early 1150s, then maybe looking at his lifespan, he was born perhaps 20 years later, could be, you know, plus or minus 10 years, we can't be sure. So he really is someone who came not as a witness to this particular set of experiences, but someone who sat down and spoke avidly to people who had been there and had seen it with their own eyes.

[Chris] And I find it interesting that John mentions how it's almost as if the Lord of the Manor who took in the children, he almost talks about, yeah, he told this story over and over and over, like he dined out on it for years.

[Simon] Absolutely, but wouldn't you?

[Chris] Yeah, absolutely.

[Simon] Well here maybe we can talk a little bit more about John's book and I don't know if you have any suggestions for further reading, but John has rather destroyed this section of our podcast because normally we have five or six titles, but here we pretty much, I mean, John's book has effectively eliminated all other competition in the field. Even worse than eliminated, he's effectively absorbed all other competition in the field because he's read everything. And if you want to know about some crazy theory from the 70s that the Green Children are actually from Alpha Centauri, you know, go to page 82 in John and you'll find the details without having to go down the library shelves. I think what I find most exciting about John's book, and I wonder Chris whether you can relate to this as well, is that this is clearly an intelligent person with the right skill set. He knows medieval society very well, he knows medieval Latin and he has worried away at this problem for the best part of three decades. And for me it's a lesson of how that worrying away at something does actually pay dividends. I started reading John's writing on the Green Children when they were free essays on the internet maybe 15 years ago, a decade ago, and I have seen John slowly change his opinion on a series of questions. And I really feel that as John has got to know the subject better and as some of his ideas have come into focus, we too can benefit from this accumulated wisdom. And I like to think when I away at 19th century fairy sources, maybe when I get to my early 70s and I look back, I'll think it was worth it. All these years just plugging away, you really do make progress. Because for me, more than anything else, this book speaks to progress. We've gone from a version where we've just found this very mysterious to a version now where it remains mysterious, but I think we can be very clear that they were perceived as fairies by the locals, whatever their actual origins were. And that in itself is a big, big step forward.

[Chris] Excellent. Yes. I mean, it's just so comprehensive. I can't see that much more research could possibly be done unless we suddenly find some DNA that we can study.

[Simon] Yeah, it will be difficult to come up with scenarios whereby we could return to this with new knowledge. I'm sure there will be ingenious ideas, but just try and put yourself in the shoes of some poor young woman or man in Australia, say, who's starting a doctorate on the green children and this book comes out. Yeah. I mean, you just change subject. There's nothing else you can do.

[Chris] Yeah, there's nothing else you can do.

[Simon] Chris, anything else to add in terms of reading? Like we say, John has swept the field, but anything else that stands out?

[Chris] Well, I did some reading in Fortean Studies, Volume 4 and Volume 6. That was 1998 and 1999. So that's well before this book. And it's just nice to have perhaps a different perspective. There was an article by Paul Harris and then there was a sort of a reconsideration in 1999 by Paul Harris and John Clark. So we'll put those on the on the page, but I'm not sure how much they add, but it's kind of interesting to see the development of the theories.

[Simon] Yeah, we should have an adjective of pre-Clarkian. Before the summer of 2024, when this book arrived. How on earth can we end this? You've promised me a reading, but you've been rather elusive about what it will actually be.

[Chris] I do. I do. As usual, I've got a little thing of my own called The Green Children. Green as leeks they was, two small weeping creatures come out of nowhere that day at harvest. Bells, they said. They followed the bells from some twilight land where the sun never rose. They wore strange clothes, talked gibberish, refused bread. I think they were liars or maybe elves. Church was full the day they baptized the two, everyone watching to see if they'd vanish in a puff of smoke at the touch of holy water. The boy pined after that and died. My old woman, she helped wash the boy for burial. The color drained from his skin. He was white as a shroud. The girl behaved badly. Married, had children, we heard. She couldn't go back to that twilight land after eating our food. The way was closed. The story is still told how, as they were starving, someone brought beans on a stalk. They tore open the stems. When there were no beans, tears like emeralds fell from their eyes. THE END