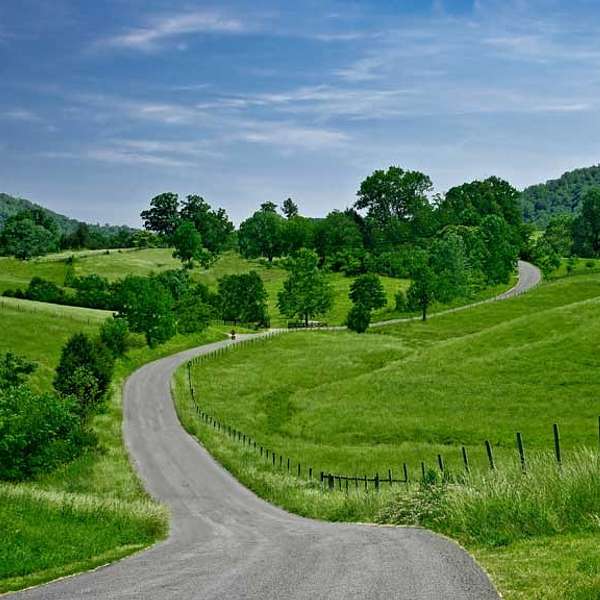

Dharma Roads

In this podcast, Buddhist chaplain, Zen practitioner and artist, John Danvers, explores the wisdom and meditation methods of Zen, Buddhism and other sceptical philosophers, writers and poets - seeking ways of dealing with the many problems and questions that arise in our daily lives. The talks are often short, and include poems, stories and music. John has practiced Zen meditation (zazen) for over sixty years.

Dharma Roads

Episode Two - Many Roads, Many Truths

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

In this episode I explain why the Podcast is called Dharma Roads, rather than Dharma Road. I also talk about notions of truth and suggest that it may be helpful to think in terms of what is useful, rather than trying to decide what is true or false. I am not suggesting that there are no truths, but that there are many truths.

EPISODE TWO - MANY ROADS, MANY TRUTHS

In this talk I want to explain why the Podcast is called, Dharma Roads, rather than Dharma Road – plural rather than single. In doing this I want to say something about the word ‘truth’ – a term that crops up over and over again in relation to religion and philosophy. I will also suggest that it may be helpful to think in terms of what is ‘useful’ rather than trying to decide what is ‘true’ or ‘false.’ The talk is a little longer than many of the other talks.

I am going to begin with an extract from a sequence of poems, titled ‘The City of the Moon,’ by the American poet, Kenneth Rexroth:

Buddha took some Autumn leaves

In his hand and asked

Ananda if these were all

The red leaves there were.

Ananda answered that it

Was Autumn and leaves

Were falling all about them,

More than could ever

Be numbered. So, Buddha said,

“I have given you

A handful of truths. Besides

These there are many

Thousands of other truths, more

Than can ever be numbered.”

[Rexroth, 2003: p.709]

It seems to me that Rexroth’s poem points to an important aspect of the Buddha’s teachings: that ‘truth’ is never absolute and final – there are always other truths besides the ones that we might consider to be important. The multiplicity of truths - ‘more than can ever be numbered’ - is something we need always to keep in mind when we argue for our own beliefs about what is true. When thinking about statements that are claimed to be true, I try to keep in mind this little saying: ‘hold lightly to what you believe, for someone, somewhere, believes the opposite.’

The belief that there is ‘one truth’ or one body of truths, so often leads to dogmatism, intolerance and, in some cases to extremism and authoritarianism. The notion that one truth, my notion of truth, should be acknowledged and subscribed to by everyone, is a prescription for coercion and conflict, as we try to impose our beliefs on others. The Buddha, and many other philosophers and teachers, considered this to be an impediment to understanding and wisdom, a road that leads to disturbance, mutual enmity and suffering. For, of course, not everyone will agree with us, not everyone will believe all the things we believe. It is important, therefore, to hold lightly to our beliefs, and to keep open to the possibility that other beliefs may be equally valid and to try to understand these other beliefs and the truths that may be contained within them.

The Buddha, Daoist sages, Socrates, the ancient Greek sceptics, and many other philosophers, advocate an approach to living, a wise road, that recognises and celebrates the diversity of beliefs, values and concepts of truth that human beings have developed, and continue to develop, as they encounter the many changing conditions in which they find themselves. This is, in Buddhist terms, a ‘middle way’ – a path of moderation, respect, empathy and understanding that unites and heals, rather than dividing and causing harm.

No individual understands, or can understand, everything. No individual has, or can have, the solutions to all the difficulties and problems that can arise as we travel on the road of life. Therefore, along with the notion that there are many truths, many dharma roads, it is important that we recognise that all knowledge and all truth values, are relative, provisional and conditional. There can never be an absolute truth in a world that is forever changing and evolving. What might be true now, at this moment, in this place, might not be true at another time in another place.

We could take this line of thought a little further and argue that the term ‘truth’ may itself be an impediment to wellbeing and wisdom, because, so often, ‘truth’ is associated with a distinction being made between two absolutes: ‘true’ and ‘false’ – as if there can be only two options and no gradient or scale in between. People say, ‘well, it is either true or false,’ or ‘it is either yes or no, good or bad, right or wrong.’ This is known as ‘dualism’ – the belief that the world can be described and defined in relation to two opposing terms – ‘this’ or ‘that’, ‘up’ or ‘down,’ ‘big’ or ‘small,’ ‘us or them.’ But of course, these terms are not absolutes – they are themselves relational, describing a distinction that may be correct at one time, in one context, but be incorrect at other times, in other contexts.

Describing the sun as being ‘big’ is reasonable in relation to the earth or one of the other planets, but in relation to our galaxy it is unreasonable. The size of the sun is finite, in that it may be measured with some accuracy, but its size in relation to other entities changes depending on the size of those other entities. Likewise, a statement may be true in one context, but false in another. ‘Justified true beliefs and statements’ – a popular way of speaking about truth in philosophical circles – may change from time-to-time as the evidence to support these statements is recognised, or not. Once, the statement, ‘the world is flat,’ seemed to be a reasonable and ‘true’ statement based on human experience and knowledge at that time. But now, of course, it is considered by most people to be a false statement, if we accept the scientific evidence that supports a view that the earth is spherical.

Statements about what is true and false, are always provisional, subject to revision in the light of new evidence and understanding. We could argue that in relation to most dualities of the ‘this-or-that kind’ it might often be the case that a particular entity or statement might be, simultaneously or at different times, both big and small, right and wrong, true and untrue. It all depends on what we are describing and comparing, and when. Keeping in mind that these are temporary statements about relationships, rather than permanent statements about isolated or separate phenomena, is crucial if we are to cope effectively with the flow of experiences. It is important to notice the relationships, and to be open to how they change, if we are to maintain a balanced view and a harmonious state of mind.

One of the problems with the kinds of dualistic thinking I have been talking about, is that we may be tempted to believe that the world is actually fragmented in this way – divided at some deep level into this and that, right and wrong, up and down, big and small, us and them – forgetting that these are relative distinctions made by humans in the face of a world that is constantly changing and evolving, made up of processes and energies that are inseparable and mutually interacting. Science recognises this, in that it constantly changes its database, terms of reference and the questions that are being asked, in the light of the experimentation and theorising that determine our current state of knowledge.

Sadly, we, as individuals, or as groups and communities, can lose sight of this provisional and relative nature of statements of what is true, and hang on to a belief that something is true even when current evidence suggests that it is false. There may well be people, even in the twenty-first century, who believe the earth is flat, just as there are definitely people who consider that global-warming is not proven and/or is not caused largely by human activity – despite overwhelming scientific evidence that this is the case. People with such beliefs consider their beliefs to be true, and any contrary beliefs to be untrue. Beliefs of this kind, no longer open to revision, passionately defended and promulgated, and unsupported by evidence, are dangerous forms of delusion that can easily lead to conflict and a failure to act in ways that might relieve suffering.

Of course, even the idea that global warming is largely the result of human activity, needs to be believed only in so far as it is supported by evidence. If the evidence were to change, we need to be open-minded enough to change our belief. Also, we need to try to understand why someone might believe that global warming is not being caused, or amplified, by human activity. Only by seeing into the reasons and causes of particular beliefs can we form a balanced view of whether they are valid or not.

There is an alternative approach to all of this, that shifts the emphasis away from a dualistic, either/or notion of truth and falsehood, to a much less divisive and more relational notion, that is: what might be useful, or not, in improving the lives of the majority - what might be helpful in alleviating suffering and increasing wellbeing, as opposed to causing harm. There is still a dualistic structure here - between doing good or doing harm, between what works in alleviating suffering and what doesn’t – but it is much more nuanced and open to endless revision. In western philosophy this approach is known as ‘pragmatism’ and is associated with a group of American twentieth-century philosophers known as ‘pragmatists,’ namely: William James, C.S. Peirce, John Dewey, Richard Rorty and others.

It is worth keeping in mind that this approach is also exemplified by the Buddha, Socrates, Daoist sages and ancient Greek sceptics who were living and teaching over two thousand years ago. The Buddha repeatedly suggests that his students should not just accept what he says, as if he is inevitably stating what is true – instead, his students should question what he says, test his advice in the laboratory of their own experience. He implies that we should decide, for ourselves, whether his description of reality and of human existence, is useful in enabling us to understand, and rid ourselves, of what he calls the ‘three poisons,’ namely, ‘anger, greed and delusion.’

Echoes of the Buddha’s approach can be found in the writings of pragmatist philosophers. The American philosopher, Richard Rorty, was very influential, and somewhat controversial, in the 1980s and 90s. Rorty argues that philosophers ‘are not here to provide principles or foundations or deep theoretical diagnoses, or a synoptic vision.’ That is, the job of philosophy is not to come up with some comprehensive statement about what is true, or a list of truths, or a system of beliefs about the nature of truth. Instead, he argues that philosophy is about trying to clarify what we are saying and thinking, trying to find ‘intersubjective agreement’ – that is agreement between the opinions and beliefs of the many - and developing ways of thinking and speaking that usefully enable us to live together with greater pleasure and less pain.

Sharing our infinitely different descriptions of the world is one of the ways in which we can do this. Rorty quotes (approvingly) the philosopher, Paul Goodman, who writes: ‘There is no one Way the World Is’. Instead, as Rorty says, there is ‘no one way [the world can] be accurately represented…[and]… there are lots of ways to act so as to realize human hopes of happiness.’ [Rorty 1999: p.33] This is an argument in favour of pluralism, encouraging us to celebrate diversity and difference – rather than trying to impose one opinion or belief (or set of truths) on everyone. The important question is not, ‘what is true,’ or ‘what is truth,’ but rather what works in enabling us to live a ‘good life’ – what helps to reduce suffering for all beings, what works in developing peace, harmony, creativity and wellbeing. This aspiration seems to me to be very similar to that of the Buddha and to the many wise men and women who act as guides on the dharma roads of awakening and understanding.

So rather, than constructing a simple, or elaborate, system of beliefs or truths, it may be more helpful to find ways of negotiating the key questions that life presents to us. For instance: How can we live a ‘good life’ in the 21st century? How can we minimise unnecessary suffering? How can we find peace in troubled times? How can we live in a way that nurtures, rather than damages, our planet? How can we pay attention to, and enjoy, even the smallest and most humdrum of experiences? How can we stand up for what we believe in, yet have respect and compassion for those who have very different beliefs? How can we develop kinship and kindness towards all living beings?

It is these questions, and the many possible ways of tackling them, that I am interested in exploring in these Dharma Roads talks. There are no final answers to these questions and no single answer that will work for everyone. We all have to navigate our way as best we can, mindful of the lessons we learn from our own experiences and from the shared wisdom of others. I hope this talk, and the others in this podcast, will be helpful to you.

References

Rexroth, Kenneth. 2003. The Complete Poems of Kenneth Rexroth. Port Townsend, USA: Copper Canyon Press.

Rorty, Richard. 1999. Philosophy and Social Hope, London: Penguin Books.