Dharma Roads

In this podcast, Buddhist chaplain, Zen practitioner and artist, John Danvers, explores the wisdom and meditation methods of Zen, Buddhism and other sceptical philosophers, writers and poets - seeking ways of dealing with the many problems and questions that arise in our daily lives. The talks are often short, and include poems, stories and music. John has practiced Zen meditation (zazen) for over sixty years.

Dharma Roads

Episode 17 - Scepticism, Buddhism & Zen - being a mindful sceptic

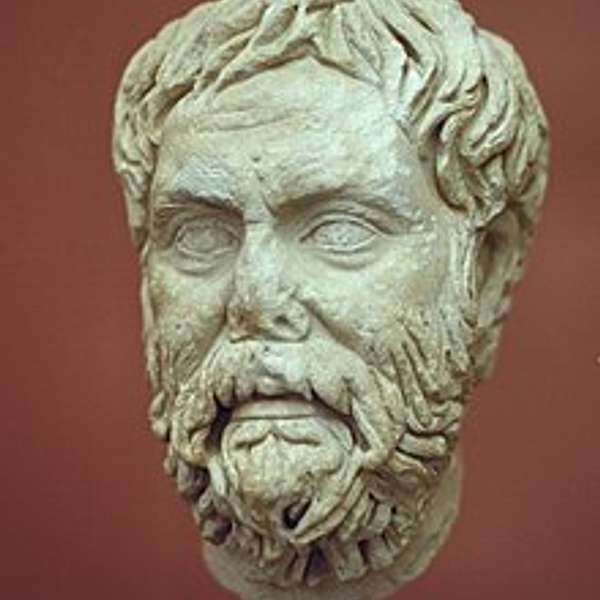

In this episode I offer a few personal thoughts on what might be called a ‘sceptical approach to Zen Buddhism,’ or, perhaps more accurately, a worldview rooted in the ideas and practices of both Zen Buddhism and the sceptical philosophy established by the ancient Greek thinker, Pyrrho of Elis – who lived from around 360 – 270 BCE. I relate these thoughts to the practice of mindful meditation and suggest ways of being a mindful sceptic.

As far as we know Pyrrho produced no writings and what we understand of his life and ideas comes to us via the writings of Sextus Empiricus who lived in the mid to late 2nd Century CE and Diogenes Laertius, who lived in the 3rd Century. These two writers drew their information from fragments of texts by Timon of Phlius, who had been a student of Pyrrho’s.

In 2013, I set up a website titled ‘Sceptical Buddhism’. Its pages were full of notes and images that traced some of the relationships I could see between my Zen practice (at that time, forty-five years or more of doing zazen) and Pyrrho’s ideas about how to deal with life’s endless ups and downs - how to realise some measure of peace and live a ‘good life.’

On the home page of the Sceptical Buddhist website, I included a few phrases and quotes that epitomised the approach I was taking. Here are a few examples:

Hold lightly to your beliefs for someone, somewhere, quite reasonably, believes the opposite.

Question, enquire, accept, let go.

The opposite of what is written here may be equally true and useful.

Learning involves the expansion of ignorance as much as the expansion of knowledge – sharing what we don’t know is as important as sharing what we think we do know.

Nothing is certain - there are no absolutes.

There is no end to sceptical enquiry - no end to awakening.

The personal statement on the home page of the website read like this:

I am drawn to a Buddhism stripped back to the contemplative embodied mind open to all that flows, to the absence of judgment and reactive commentary, to the acceptance of what is, to the moment-by-moment process of self-construction, and to the mindful awareness of interdependence and change. I am drawn to a practice that has few ornaments of ritual; that is non-dogmatic - having no attachment to beliefs that are not open to questioning and testing in the laboratory of our experience; that does not involve unquestioning attachment to a teacher or unmindful adherence to a set of rules or teachings; and that draws on learning from all quarters, including the scholarship of everyday life, mindful meditation, academic study and scientific investigation.

I still agree with these statements, and I realise that the label ‘sceptical Buddhist’ describes my position more accurately than ‘secular Buddhist.’ ‘Mindful sceptic’ may be even more apt.

The word ‘scepticism’ is derived from the Greek term, skepticos, which refers to someone who endlessly investigates, someone who goes in for skeptesthai, or enquiry – so a sceptic is an investigator who is always open to new knowledge and ready to revise their opinions. The sceptic in this sense does not have, or seek, dogmatic belief and fixed knowledge. The sceptic realises that all things change, and all entities only exist in an infinite field of relationships. The Buddhist parallel to sceptical enquiry can be clearly seen in the practice of zazen or mindful meditation – that is, a clear-sighted awareness of moment-by-moment consciousness, a non-judgmental and non-reactive observation of experience as it happens. There is no end to the enquiry and no bed-rock or fixed essence to be found underlying our fluid consciousness. The investigator, whether Buddhist or sceptic, or both, finds equilibrium, understanding and compassion through the process of investigation, through clear-sighted dispassionate observation – coming to terms with the complex dynamics of life as it lived, not as it is imagined, idealised or wished to be. The mindful meditator is constantly awakening, growing in understanding and developing as a living being.

As far as we can tell the Buddha, like Pyrrho, urged his students not to blindly accept everything he said. Unthinking attachment to a teacher, or to an abstract idea or belief - however eminent or celebrated the teacher might be - was a hindrance to liberation and insight. Any teachings need to be tested within the laboratory of everyday life, tested by each individual to ascertain how effective they may be. The insight meditation teacher, Joseph Goldstein, quotes the Buddha as saying: ‘Don’t believe anyone. Don’t believe me. Don’t believe the teachers. Don’t believe books or traditions. Rather, look to your own experience. In that way we become our own refuge, not dependent upon any external authority or system.’ (in Walker 1987: 640) Without questioning and testing against one’s own experience any teaching can become a dogma to be unthinkingly followed and any teacher can become a dictator to be submissively obeyed.

Pyrrho is reputed to have been a painter before he became a philosopher or investigator. He is also thought to have accompanied Alexander on his expedition to north-west India in 327 BCE and may well have conversed with Indian philosophers and teachers from different traditions - including Brahmins, Buddhists and Jains. There seems to be very persuasive evidence that a cross-fertilisation of ideas and practices was happening at this time and what we know of sceptical thought from this period has affinities with aspects of Indian practical philosophy, and vice versa. It is important to remember that philosophy at this time, in both cultures, was seen as a practical attempt to develop effective ways of living a good life rather than as a purely intellectual or academic endeavour.

As I got to know more about sceptical ideas in western philosophy, I found a recurring thread of positive doubt, a celebration of uncertainty and a tolerance for all viewpoints, this seemed to echo what I was finding out about Daoism and Zen Buddhism, and it appeared to be at odds with the usual idea that what we should seek is certainty, absolute truth and one coherent solid view of the world. These sceptical ideas of multiple viewpoints, beliefs and ways of picturing the world also seemed closer to what the arts were concerned with – giving voice to many viewpoints, picturing the world from many perspectives – none of which is right or final. This does not mean that the sceptic doesn’t have opinions or beliefs but only that he or she doesn’t consider them as absolute or universally valid – they are as sceptical of their own views as they are of the views of others. Holding lightly to any view is wise. Listening carefully to other views is also wise.

*

Another point of similarity between Buddhism and Pyrrho’s scepticism is in their thinking about the relatedness of everything. I will try to sketch out some of this thinking. We are enmeshed in our surroundings, implicated in the world, interdependent with everything we are supposedly not! Our breathing in and out is, practically and symbolically, an affirmation of relatedness. We exist in a relational universe. We are unable to exist in a vacuum or in isolation from our surroundings. No entity has a fixed essence or existence independent from everything else – all entities are empty of self-existence. This interdependence and interrelatedness is what Buddhists refer to as sunyata – often translated as ‘emptiness’ or ‘the void.’ The indefiniteness of boundaries is what ancient Greek sceptics refer to as aoristia. Within both of these traditions, relatedness and boundary-lessness are fundamental conditions of existence. To believe, and act on the belief, that we are separate from the world, or from other beings, is to be deluded.

From the sceptical point of view, the understanding that there are no definite and fixed boundaries to things, leads to the understanding that we can never be certain about anything, and that we can never be sure that our ideas, beliefs, perceptions and intuitions are true or justifiable, let alone absolute, permanent or universal. Indeed, we have to recognise that all ideas, beliefs and facts or units of knowledge, are provisional and partial. For this reason, it is sensible to suspend judgement, to always keep in mind that any assertion or argument is open to a legitimate counter-assertion or argument, and that any so-called truth is open to revision, qualification and opposition. The sceptical term for suspension of judgement is epoché.

The American art critic and theorist, Thomas McEvilley, wrote a rather wonderful book about ancient Greek and Indian philosophy, titled: The Shape of Ancient Thought – first published in 2002 and based on thirty years research. McEvilley suggests that epoché, suspending judgment, was the first part of a process that could help develop peace of mind. He describes this sequential process in this way: epoché ‘could lead to a state of inner freedom from the domination of linguistic categories (aphasia), which in turn will steady into an effective balance (arrepsia) which is naturally and effortlessly followed by a state of imperturbability (ataraxia).’ (McEvilley 2002: 420)

My interpretation of this sequence goes like this: when we suspend judgment, we are also suspending any belief that the world can be divided according to linguistic categories, labels or statements – we can only glimpse in silence the primary unity and interconnectedness of everything. This is a state of aphasia. This silence and freedom from categorising, labelling and arbitrarily dividing-up the world, gives rise to a state of balance, neutrality or what some Buddhist’s would call, equanimity. That is, we have a clear, balanced view of how things are, setting aside our own preferences and preconceptions. This is arrepsia. This clear, balanced view gives rise to a feeling of tranquillity, freedom from worry or peace of mind – that is, ataraxia. And freedom from worry is a significant contributing factor to anyone’s mental wellbeing. The cultivation of imperturbability, peace of mind and wellbeing are key intentions of sceptics such as Pyrrho – as they are of the Buddha.

Given that knowledge is always uncertain and relative, the sceptic considers their philosophy of life, their way of doing, as a process of open-ended enquiry, endless investigation - realising that there is always more to be found out – a life of questioning, positive doubt and imaginative re-interpretation. Not seeking any final or absolute truth, but simply being curious, enjoying the enquiry for its own sake. This could also be seen as epitomising the artistic and scientific life. The purpose of scepticism is not philosophical enquiry but living enquiry (like Buddhism) – developing a way of living that is balanced, at peace, poised in the moment between past and future – the middle way – what in Buddhism is known as sukha. As a later sceptic, Sextus Empiricus, points out, there are dogmatic philosophers, who think they have found the truth; negative dogmatists, who believe that the truth cannot be found; and the sceptics, who are not committed either way – they are still investigating.

The scepticism of Pyrrho articulates a profound critique of dogmatism. Employing logical argument sceptics set out to demonstrate that all opinions are open to contention and counter-argument - and are therefore conditional and relative, unworthy of being given the status of certain or absolute truth – which is what the dogmatist claims. This leads a sceptic to acknowledge that all viewpoints, ideas and beliefs are worthy of respect or passing interest, yet it is best not to become attached to any one in particular – a balanced and tolerant position, rather than a position of taking sides, intolerance and imbalance.

This approach to ideas of truth as being relational and provisional, does not mean that a sceptic like Pyrrho or the Buddha thinks that there are no truths or that establishing a fact is not important. It is rather that they consider what we think of as ‘facts’ should always be open to revision in the light of changing evidence, enquiry and agreement. Likewise, the statement that ‘this is true’ or ‘this is the truth’ should always be considered in the context of who is saying it, when they are saying it, why and where – because truth claims always need to be seen in relation to the status, power, intention and knowledge-base of the claimant. The claim that ‘the earth is flat is a true statement’ made by a person in the 10th century, will probably be evaluated in a very different way to the same claim being made in the 21st century. Individual and collective understanding evolves over time as we investigate and learn – and this process determines what might be considered to be true or factual.

Pyrrho also urges us to acknowledge that opinions and judgments are always relative – they are abstractions or blindfolds that take us away from, or cloud our experience of, things as they appear to us – ‘phenomena in themselves.’ This phrase ‘phenomena in themselves,’ can be seen as close in meaning to the Zen notion of ‘tathata’ or ‘suchness’ – that which we perceive unblinkered by preconceptions and prejudices. Pyrrhonists, such as Sextus, and many Zen Buddhists, would appear to share a suspicion that linguistic ideas and theories, often in the form of preconceptions and habits of thought, tend to cloud our perceptions, obscure rather than reveal the suchness or actuality of what appears to us from moment to moment. Puncturing this veil of words, theories and abstractions is one of the tasks of the sceptic and Zen teacher. Accepting appearances, without clinging to them or believing them to be fixed or absolute, would seem to the sceptic and Zen practitioner, to be a reasonable approach to good living.

From a sceptical point of view, human history can be seen as being littered with conflicts fought in the name of dogmatic truths, or false certainties, of every persuasion. If we are to be free of error and to be free ‘of the domination of linguistic categories,’ we have to be open to the indeterminacy of things, the awareness that all things are without essence or self-existence and are always subject to changing conditions.

There are endless ways of picturing an apple just as there are endless ways of thinking about ourselves and the world. Wisdom grows by trying to take account of as many perspectives as possible – always being open to the possibility that there is more to be discovered. Sceptical enquiry, like Buddhist awakening, is a process that is never complete. Although they are now cliches, terms like ‘don’t-know mind’ and ‘beginner’s mind’ still convey a sense of how Pyrrho and Zen teachers encourage us to approach life – open rather than closed, always ready to revise what we think and believe in the light of each fresh experience.

*

In case you are interested, Pyrrho’s approach to life and his embrace of positive uncertainty, can be seen as having similarities to the thinking of a number of later sceptical writers, for instance: the wonderful French essayist, Michel de Montaigne (1533-92), the Scottish enlightenment philosopher, David Hume (1711-76), and the twentieth-century American Pragmatists, John Dewey, William James, C.S.Peirce and Richard Rorty. There are also parallels with the writings of Zen teachers, for instance: the thirteenth-century Japanese master, Eihei Dogen, and the twentieth-century Japanese teachers, Kosho Uchiyama, and Shunryu Suzuki – who coined the phrase ‘beginner’s mind,’ and the Korean teacher, Seung Sahn – who writes about ‘don’t-know mind.’ These Zen teachers seem to me to epitomise what it is to be a mindful sceptic.

Remember:

Everything changes - nothing is certain.

There is no end to sceptical enquiry - just as there is no end to awakening.

Thank you for listening and bye for now.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Danvers, John. 2012. Agents of uncertainty: mysticism, scepticism, Buddhism, art & poetry. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Empiricus, Sextus. 1990. Outlines of Pyrrhonism. New York: Prometheus Books.

McEvilley, Thomas. 2002. The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies. New York: Allworth Press/School of Visual Arts.

Mitchell, Stephen, ed. 1976. Dropping Ashes on the Buddha: The Teaching of Zen Master Seung Sahn. New York: Grove Press.

Suzuki, Shunryu. 1970. Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. New York: Weatherhill.

Uchiyama, Kosho. 2004. Opening the Hand of Thought: Foundations of Zen Buddhist Practice. Boston: Wisdom Publications.

Walker, Susan, ed. 1987. Speaking of Silence: Christians and Buddhists on the Contemplative Way. New Jersey: Paulist Press. Joseph Goldstein is quoting his own version of an extract from the Anguttara-nikaya.