Dharma Roads

In this podcast, Buddhist chaplain, Zen practitioner and artist, John Danvers, explores the wisdom and meditation methods of Zen, Buddhism and other sceptical philosophers, writers and poets - seeking ways of dealing with the many problems and questions that arise in our daily lives. The talks are often short, and include poems, stories and music. John has practiced Zen meditation (zazen) for over sixty years.

Dharma Roads

Episode 16 - John Cage & Zen: a chattering silence

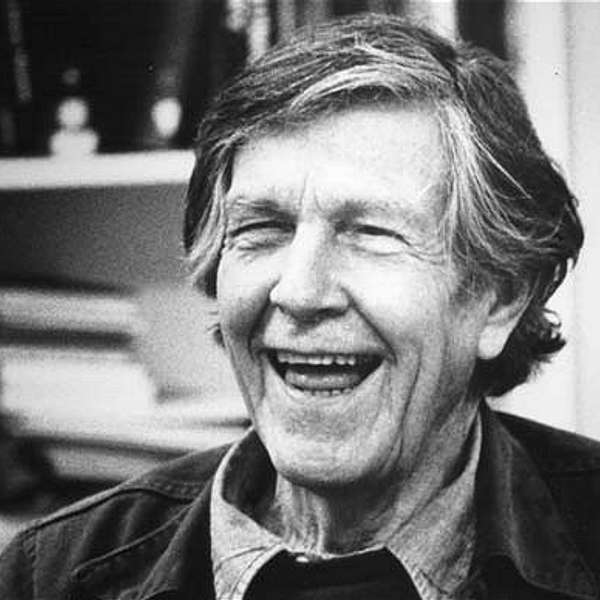

In this extended episode I explore some of the ideas and works of the American multi-disciplinary artist, John Cage – who was born in 1912 and died in 1992 – particularly noting parallels with the practice of zazen and mindful meditation. In 1950, Cage met D.T. Suzuki and began to learn from him about Zen. Cage was never a Zen practitioner, in the usual sense, but his understanding of Zen ideas, along with his study of Daoism and Vedanta philosophy, had an enormous impact on his work as composer, writer and artist. It was in 1950 that Cage began to use chance procedures as an important part of his compositional methods – particularly using the iChing, or Book of Changes, and dice, to determine many, if not all, aspects of his music – including duration, tonal values and ‘silences.’

In this extended episode I explore some of the ideas and works of the American multi-disciplinary artist, John Cage – who was born in 1912 and died in 1992 – particularly noting parallels with the practice of zazen and mindful meditation. In 1950, Cage met D.T. Suzuki and began to learn from him about Zen. Cage was never a Zen practitioner, in the usual sense, but his understanding of Zen ideas, along with his study of Daoism and Vedanta philosophy, had an enormous impact on his work as composer, writer and artist. It was in 1950 that Cage began to use chance procedures as an important part of his compositional methods – particularly using the iChing, or Book of Changes, and dice, to determine many, if not all, aspects of his music – including duration, tonal values and ‘silences.’

Cage was a very influential figure in music, literature, poetry, performance, visual art & art theory.

Cage reacted against some of the key beliefs of ‘modernism’ in the arts. That is, he argued against notions of ‘self-expression’; the artist as a subjective agent of ‘authentic’ acts; and the separation of the arts into clearly identified disciplines, each being true to their own materials and processes. He was also sceptical of the division between artist and audience, and of the idea that the artist was a special person – the ‘artist as genius.’ Cage considered the arts as ways of paying attention to what is happening all around us all the time. In this sense everyone is an artist as long as they are awake to themselves and to the world. We might say that Cage advocated a kind of mindful approach to living – what we might call ‘Zen minding.’

Cage mentioned how early on in his career as a composer, he made compositions that expressed joy or sadness, only to find that many people felt his joyful pieces were sad, and his sad pieces were joyful. For Cage this suggested that the whole idea of art as expressive of emotion was misguided. He began to develop a different approach. Instead of considering music as a vehicle of expression, symbolism and a ‘message,’ he began to explore the possibility that sounds could be just sounds - nothing less and nothing more than themselves. The function of the composer, he argued, was to 'liberate sounds from abstract ideas,’ and to enable people to hear the beauty and uniqueness of sounds, notes and phrases, without searching for what they mean or express.

When his music was performed, Cage considered the audience as creative participants, not passive spectators, with sounds, not as vehicles for ideas, but as moments of experience – unique and never-to-be-repeated. He encourages the ‘audience’ to pay attention to what is happening, to listen, to engage with the sound world all around them - in other words, to be mindful.

PREPARED PIANO. From the late thirties to the late forties, Cage earned a living as an accompanist to various dance groups and choreographers, writing music for an array of percussive instruments including found objects like tin-cans, kitchen paraphernalia and metal sheets. These were cheap and easily available and demonstrate Cage’s inventiveness in practical and musical matters. All Cage needed were musicians to perform the works, but performers had to be paid and this presented Cage with a problem, as he earned hardly enough to support himself let alone others. It didn’t take long before he found a radical and effective solution to this problem. Cage’s father had been an inventor and Cage junior was certainly inventive. He was well aware that most of the halls in which dancers rehearsed had a piano as part of the furniture and by inserting various materials in between the piano strings (nails, bottle-tops, bits of felt, rubber, silver-paper, and so on) the usual sounds of the piano could be modified into a percussive orchestra within the one instrument.

I am going to play an excerpt from Sonata 4 of Cage’s ‘Sonata’s and Interludes,’ written for prepared piano between 1946 and 1948 – Giancarlo Simonacci is the pianist in a recording from 2006 on the Brilliant Classics label. Notice how the gaps between sounds are as important as the sounds themselves. Fragments of melody and rhythm are arranged in sequences that have no obvious feeling of development or resolution – they are presented as audio experiences to be appreciated as sounds in themselves. In a sense Cage provides us with opportunities to experience the ‘suchness’ of each aspect of the field of sounds – such as we might experience during a period of zazen or mindful meditation. Here is Sonata 4:

EVERYDAY SOUNDS. Often, the 'noise' of everyday life, usually excluded from 'serious music', was included by Cage in his works. Everyday sounds were reclaimed as music. His compositions often provided an opportunity to recognise the 'empty and marvellous' beauty of our everyday sound world. In doing this Cage questioned the usual clearly defined boundary between artist and audience and between ART & LIFE.

I would now like to play an extract fromRadio Music – composed by Cage in 1956 and realised here by Juan Hidalgo and Walter Marchetti in a recording made in 2007 for Cramps Records. The piece is composed for 1-8 performers, each with one radio. Chance procedures were used by Cage to determine changes in the radio frequencies, duration, volume and so on. Each realisation of the work is unique and indeterminate – the sounds and silences cannot be predetermined and are full of surprising coincidences – fragments of music, announcements and conversations - whatever is being broadcast on those frequencies at that particular time on the day of the performance and recording. Here is Radio Music:

CAGE TEACHING. Cage introduced many of his ideas in a course that he taught between 1956 and 1960 at the New School for Social Research in New York.Several young artists attended Cage’s class and they began to put his ideas into practice in their own work. These artists included Allan Kaprow, George Segal, Dick Higgins, Alison Knowles George Brecht, and Yoko Ono – all of whom developed Cage’s ideas into performance art, ‘Happenings,’ and sculpture. The poet, Jackson MacLow also attended, and developed a performative approach to poetry that was very indebted to Cage. Well-known artists, Robert Rauschenberg and Jaspar Johns also learnt a lot from the compositional ideas of Cage – as did the composers Christian Wolff, Earle Brown and Morton Feldman. Cage’s long-term partner, the choreographer, Merce Cunningham, developed an approach to dance that has many affinities with Cage’s work in music and performance.

4’33”. On August 29, 1952, one of Cage’s works had its premiere near Woodstock in New York state. Its title is 4’33” and it was both very controversial and very influential. Here is a description of the work from Encyclopedia Britannica:

Cage conceived the piece in 1948, when he gave it the working title ‘Silent Prayer.’ The work’s manuscript declared that it was written ‘for any instrument or combination of instruments.’ It then specified that there were three movements of set duration—33 seconds, 2 minutes 40 seconds, and 1 minute 20 seconds, respectively. For each movement, Cage’s sole instruction to the performer(s) was ‘Tacet’ – the Latin notation meaning, ‘[it] is silent’ - used in music to indicate that the musician is not to play. For the first performance of 4′33″, pianist David Tudor used a stopwatch, opening or closing the keyboard lid at the designated intervals.

Apparently, some members of the audience left in disgust, but many remained and began to pay attention to what was going on all around them. Cage’s work provided the audience with the opportunity to attend to the whole spectrum of sounds, (and sights and other phenomena), that happened to arise during this particular four minutes and thirty-three seconds. In Cage’s view the ‘subject’ of ‘his’ music is not himself (the composer or author) but the sounds that occur within the duration of the work. He is not trying to express particular feelings or ideas of his own, but rather to let the participants in the music (‘performers’ & ‘audience’) listen more attentively, to perceive the world ‘as it is’ not as they (or he) might wish it to be.

Let us listen to the first movement of Cage’s work – just 33 second, when I won’t say anything – a chance just to pay attention to whatever occurs wherever you are at this moment: 33 seconds.

In passing I’d like to mention that many works from the 1960s by Yoko Ono are in the spirit of Cage’s attempts to shift the emphasis in art away from self-expression on the part of the artist, to opening up the awareness of everyone who engages with art. Here are a couple of examples of Ono’s scores for actions from the MUSIC section of her 1964 book, Grapefruit:

BUILDING PIECE FOR ORCHESTRA consists of this instruction or suggestion: Go from one room to another / opening and closing each door. / Do not make any sounds. / Go from the top of the building / to the bottom.

In another score, CITY PIECE, she asks us to: Step in all the puddles in the city.

Ono’s ‘scores’ are invitations to act in certain ways, to listen, to walk, to explore and to imagine – to pay attention to what is being done and to notice different aspects of the everyday world. Ono is encouraging us to realise creative ways of being in the world – to manifest our playful ‘beginner’s mind’ or ‘Buddha Nature.’

CAGE & CHANCE. Another important aspect of Cage’s work is the way in which he makes use of complex compositional methods to create a distance between himself as composer and the works which emerge under his name. By using chance procedures to make decisions about all aspects of his music-making, he challenges the usual idea that the composer ‘writes’ his music in order to express an idea or emotion. Cage lets go of the decision-making and control that most composers would see as being essential to their role as an artist. In a sense, Cage’s work shifts from being egocentric to being eco-centric – that is, his music is a manifestation of a whole network of creativity, including Cage himself, as well as performers, audience, instruments and compositional tools – all having equal involvement in how a work is made and heard.

In Cage’s approach to music-making, or sound-making, he tends to give as much attention to silence as to sound. Indeed, Cage questions whether true ‘silence’ even exists. In the summer of 1952, Cage went to Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. There he had the opportunity to enter an anechoic chamber developed by acoustic engineers who wanted to create a space that was completely sound proofed. No sounds could enter from outside. When Cage came out of the chamber, he challenged the engineers who had made it by pointing out that it wasn’t silent – in fact he could hear a low-frequency sound and also a high-frequency sound. The engineers answered by telling him that those sounds weren’t coming from outside the chamber but were actually the sounds of Cage’s own nervous system and the circulation of his blood. According to Cage this was a pivotal insight. He mentions how it was this experience, the realisation that silence was a fiction, that led him to compose 4’33”. (Larson 2012:269)

One other characteristic of Cage’s music is worth mentioning here. Much of Western music, certainly between the seventeenth and late nineteenth centuries, has involved the writing of melodies and tonal progressions that have a narrative purpose. Musical compositions, in a sense tell a story. They develop, note-by-note, movement-by-movement, progressing towards a resolution of some kind at the end. In Cage’s work, on the other hand, there is often no sense of development, narrative, or progression. Notes and phrases occur as entities in themselves. Sounds to be heard as sounds, not as episodes in a linear story.

CAGE QUOTES. Here are a few statements made by Cage, that provide a flavour of his thinking:

‘Look at everything. Don’t close your eyes to the world around you. Look and become curious and interested in what there is to see.’ (Larson 2012: 81)

‘The world, the real, is not an object. It is a process […] The function of art is to draw us nearer to the process which is the world we live in.’ (source unknown)

Cage often quoted a statement by Coomaraswamy: ‘the responsibility of the artist is to imitate nature in her manner of operation.’ (Kostelanetz 2000: 239) Cage considered the artist’s role not to be to express his- or her-self, but to generate structures that approximate to the processes that operate in nature. These structures are complex, usually made up of many linear determinate strands, interwoven and layered in such a way as to generate an indeterminate, and often surprising, artefact. Hence Cage’s use of chance methods to echo the role that chance and randomness play in natural processes of growth, reproduction and evolution.

Cage said many times that his intention ‘is to affirm this life, not to bring order out of chaos nor to suggest improvements in creation, but simply a way of waking up to the very life we’re living, which is so excellent once one gets one’s mind and one’s desires out of its way and lets it act of its own accord.’ (Larson 2012: xv) This could easily have been said by a Zen teacher.

Cage often said that for him the purpose of art is ‘to sober and quiet the mind so that it is in accord with what happens.’ (Brown 2000: 45) In other words, art is a way of settling the mind so that we really notice what is going on and are at peace with ourselves and the world. Art, in his view, is very similar to a life of prayer or contemplation, and to a life of being mindful and taking care.

CAGE & MYCOLOGY. Throughout his life Cage was interested in fungi – he became an expert amateur mycologist – even winning, in 1959, an Italian radio quiz programme answering questions on mushrooms. In the final episode, with 5m lire at stake (the equivalent of about $8,000 or £3,000 in today’s money), he was asked to list the 24 names of the white-spored Agaricus family of fungi, as identified in GF Atkinson’s Studies of American Fungi. He not only named them all, but named them in alphabetical order, prompting sustained applause from the audience.

Cage's music tends to be open and inclusive. It is often characterised by a high level of indeterminacy and unpredictability. Silence is as highly valued as sound. There is often no sense of development, narrative, or progression, in his compositions. To many people his works are excruciatingly boring, or infuriating, or amusing, or deeply disturbing. Through complex compositional methods Cage often makes a distance between himself as composer and the works which emerge under his name. He places value upon non-intentionality - a very indirect connection between himself and his work. And yet his work and ideas are often extremely distinctive, easily identified as being 'his'. In his work, performers and audience are empowered, encouraged to play an active role as participants rather than a passive role as spectators.

Cage's ideas about art and life tend to challenge basic assumptions about aesthetics and critical judgment. He often says that his work as a composer is done in a spirit of enquiry – asking questions about music, sound and the world about us. Here are some of the questions that occur to me:

What does a composer/artist do in the world? If sounds emerge as a result of 'chance operations,' how can anyone be considered as having 'composed' them? And if they haven't been composed, how can they be evaluated as music? Are any sounds or sequences of sounds to be considered as being 'better' or more 'beautiful' than any others? If the sounds don't 'say anything,' or have any intended meaning, what is the point of making them or listening to them? Cage considers his works as being non-representational. They do not stand for anything else. And yet we often associate non-representational works with abstraction, while Cage's approach prioritises the concrete actuality of sound. Certainly, this is a long way from 'expressive' or 'symbolic' theories of art. Many have argued that Cage's philosophy of music leads inevitably to the end of 'music' as we know it – I wonder what you think?

Underlying Cage’s approach to artmaking was a lifelong belief that everyone would benefit from paying more attention to the sights, sounds, scents, tastes and tactile qualities of the world around them. Cage advocated and practiced mindful awareness as an artist, composer and writer, and in his everyday life. His anecdotes are full of surprise and fascination at the things and events he noticed.

Here’s one example:

‘My grandmother was sometimes very deaf and at other times, particularly when someone was talking about her, not deaf at all. One Sunday she was sitting in the living room directly in front of the radio. She had a sermon turned on so loud that it could be heard for many blocks around. And yet she was sound asleep and snoring. I tiptoed into the living room, hoping to get a manuscript that was on the piano and get out again without waking her up. I almost did it. But just as I got to the door, the radio went off and Grandmother spoke sharply, saying: “John, are you ready for the second coming of the Lord?”’

I would like to end this brief introduction to the ideas and practices of John Cage with a couple of texts I wrote in the 1990s. I wanted to evoke something of the spirit of Cage – the way in which he lived his life encouraging us to open our ears to the sound-world that surrounds us all the time, and to open our minds to indeterminacy, to chance events and the endless surprising routine of everyday life. Cage is an advocate for being mindful – for opening our ears, eyes and minds to what is going on all around us. If we can get our preconceptions, and our thinking, listening and seeing habits out of the way, life becomes full of endless delight and wonder. This is Cage’s view of the creative life, and it has many parallels with the practice of zazen or mindful meditation.

In the following two texts, I have gathered together some fragments of Cage’s writings – composed with a combination of chance and determinate methods to give a flavour of his thought. Accompanying my texts is a recording of Cage’s composition, Eight Whiskus, composed in 1985. The viola player is Maurizio Barbetti and the recording is on the Stradivarius label:

Cage’s Tales 1

The role of the composer is other, is no longer, is being, is free, is a wild goose chase, full circle back again, to piano & dry fungi, direction (no stars), woodpecker solos & a startled moose

Our poetry now is the realisation that we possess nothing

Out of a hat comes revelation & a pianist. On the way, she said she would play slowly. On the way she would play slowly. She said on the way she would play, play slowly. Everything, he said, is repetition. Slowly she would play. She would say playing slowly she hoped to avoid making mistakes, but there are no mistakes – only sounds, intended & unintended. A glass of brandy

I was in the woods looking for mushrooms. After an hour or so Dad said, “Well, we can always go & buy some real ones”. Mother said, “I’ve never enjoyed having a good time”

There are already so many sounds to listen to. Why then do we need to make music?

We must work at looking with no judgement, nothing to say. All art has the signature of anonymity

Sounds take place in time. Dance takes place with one foot in the grave. We’ve paid our bills. Art is a job that will keep us in a state of not knowing the answers

Cage’s Tales 2

one winter, touring, weaving & dancing, tending

a grave the table is real, in every sense twenty

people in the woods a taxi downtown we have

the impression that we’re learning things, the years

pass, we’re still alive, everything is God, nothing much

to do one of the girls said, “listen”, I just sat there, listening

this is not idle talk we take things apart in order that they

may become fish, when she jumps in the water,

asks, “am I a butterfly”? even in broad daylight,

the Four Mists of Chaos: thought, stones and

emptiness of sand walking in a thunderstorm

from one village to another blind, covered with

sores stumbling over something he fell in the

mud she would never steal again wearing high

heels, furcoat, and a rose in her black hair she

may have been thinking of the mushroom

when it is terribly dry, a rainbow makes good sense

just something natural no more, no less

Thank you for listening and bye for now.

REFERENCES

Brown, Kathan. 2000. John Cage Visual Art: To Sober and Quiet the Mind. San Francisco: Crown Point Press.

Cage, John. 1979. A Year from Monday. Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press.

Cage, John. 1994. Silence. London: Marion Boyars.

Kostelanetz, Richard, ed. 2000. John Cage Writer: Selected Texts. New York: Cooper Square Press.

Larson, Kay. 2012. Where the Heart Beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists. New York: Penguin Press.

Nyman, M. (1999) Experimental Music: Cage & Beyond (Music in the Twentieth Century), Cambridge University Press.

Ono, Yoko. 2000. Grapefruit. New York: Simon & Schuster.

4’33” in Encyclopedia Britannica – online at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/433-by-Cage accessed 12 June 2023.