An Itinerant Geographer

An Itinerant Geographer is a continuing series of geographical essays by Bret Wallach, professor emeritus of geography at the University of Oklahoma.

Greatmirror.com has accompanying photographs. Substack has visually attractive transcripts.

"The Itinerant Geographer" was the title of a meticulous newsletter formerly published by the Geography Department at UC Berkeley. It was a labor of love compiled and written by Wallach's academic advisor, the late James J. Parsons.

An Itinerant Geographer

Tel Aviv and Jerusalem

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

For photos, see greatmirror.com

For a transcript, see

https://www.buzzsprout.com/1970784

On New Year’s Day, 2019, I flew to Dallas and then on to Tel Aviv via Paris. I took my shoes off in a cheap hotel. The clock said it was midnight, but for me it was four in the afternoon, so a few minutes later I put my shoes back on and walked the one block to the beach. I took my shoes off a second time, but it had stopped raining an hour earlier, and the hard-packed sand was cold, so I went back to the hotel and somehow fell asleep. It’s a strange world where you can walk into an aluminum tube and, twelve or twenty hours later, discover that time has slipped half a day. I once boarded a plane and muttered to the pilot, who was standing at the door, something like, “The machine never stops.” I thought that was pretty edgy, but he one-upped me and said, “You can’t kill the beast.”

My hotel was in a Tel Aviv neighborhood containing about four hundred militantly modern low-rise apartment buildings from the 1930s. UNESCO, which put the neighborhood on its World Heritage list in 2003, calls it the White City. I call it Bauhaus by the Beach.

The Bauhaus style, established in Germany largely by Walter Gropius in the 1920s, said goodbye to social status expressed in architecture. Good riddance to facades so heavy with classical ornaments that four story-buildings seem about to sink into the earth. In a welcome coincidence, Bauhaus simplicity was also the cheapest thing on offer at a time when most immigrants landing in Palestine didn’t carry letters of credit.

Despite its simplicity and economy, I don’t much like the Bauhaus style. Some years ago, I made a day trip from Berlin to Dessau, home of the Bauhaus in its peak years. I knew I was looking at something famous but also something I didn’t much like. Shades of seeing with your ears: I recognized many of these buildings and knew that I was supposed to respect them, but they looked like the houses I drew with crayons in third grade. I still think that those flat roofs are an invitation to leaks.

Still, I’m not objecting to UNESCO’s listing this neighborhood. The world heritage list now includes an abandoned Uruguayan slaughterhouse whose corned beef was a chapter in the history of industrialization, and I’m happy with that. Heritage is heritage, whether you like it or not. I’d be happy to see Lakewood, California, or Wynnewood, Texas, on the list as examples of post-war American suburbia. (I’d prefer them to a Levittown just because they’re less well known.) More slaughterhouses, I say; a lead smelter would be good, too. I’ll all for learning about what we’ve done to this planet.

The White City is filled with two- or three-story apartment blocks whose only ornament is balconies, usually protruding though occasionally recessed. The protruding balconies usually terminate in quarter-circles curving back to the wall. Alternatively, they have square corners so sharp you could cut paper on them. They’re dead plain, but penniless immigrants arriving in the 1930s must have thought that they had died and gone to heaven.

Guidebooks often point to Pinsker 23. (Addresses in Tel Aviv are arranged with the street name followed by the number.) The name Pinsker comes from Leon Pinsker, a medical doctor who grew up with the pleasant delusion of Jewish assimilation. Pogroms in 1882 changed his mind. Pinsker then published Auto-Emancipation a decade before Theodor Herzl published his better known The Jewish State. Overshadowed, Pinsker hasn’t been forgotten. Forty years after his death in Odessa in 1891, he was reburied at a site fit for biblical patriarchs, a natural cave in the Hebrew University’s Botanical Garden.

Pinsker Street was lined with rows of curbside bollards that would keep everything short of a tank from climbing the sidewalk. The sidewalks were bordered on the other side by knee-high walls and then by five feet of plantings. Then, one apartment building after another: all of three stories, and almost all with balconies, conceived, I expect, as a way of granting sunshine to immigrants historically deprived of it.

Pinsker 23 was an exception, an econobox about forty feet wide and a hundred deep. Designed in 1936 by Philip Hutt for thirty-five single women, Pinsker 23’s windows were spaced along three parallel ribbons around a shoebox. The most distinctive feature of the building was a squared-off bump protruding two feet from the middle of the façade. The bump enclosed the building’s entrance and main stairway. Many of the black-glazed tiles around the entrance were gone, and the swinging double doors were nicked and smudged. The narrow hallways on each floor were paved with golden-glazed tiles, but they were obscure in the darkness until a motion sensor turned them on. I had to wait a second or two before the lights clicked on to reveal doors as plain as the sides of a piano crate.

Not every immigrant arriving in early Tel Aviv was broke, and a good place to look for exceptions is Rothschild Avenue, one of the few streets in central Tel Aviv with a planted median. In 1933 a house was built here for a Dr. Sadovsky. Carl Rubin, the architect, gave the doctor another Bauhaus brick with the entrance at a corner where a cube was removed. Perhaps each floor covers three thousand square feet, and the house originally had three floors. That’s a lot of room, even if you set aside one floor for a clinic.

Rubin, the architect, had been born in Ukraine and had studied in Vienna. He moved to Tel Aviv in 1920 at age 21 but later returned to Germany to study with Erich Mendelsohn. Back in Tel Aviv in 1932, he got the Sadovsky commission. I know nothing of Dr. Sadovsky and little of the subsequent history of the house, but in 2007 it sold for seven million dollars. It was then popped up to four stories and chopped into a dozen apartments. A two-bedroom unit, every interior surface harder than ice, was for rent in 2019 at about thirty-eight hundred dollars monthly. What would the women of Pinsker 23 have made of such prices? Zionists, like Bauhaus architects, disdained bourgeois materialism, and if the women of Pinsker 23 had remained faithful to Zionism, as I expect they did, they would have been disgusted at the thought that Europe’s sickness had followed them. A million dollars in every pocket may be the American and even the Israeli dream, but it wasn’t theirs.

I kept bumping into this contradiction. It happened again as I walked along HaYarkon, the northbound street one block back from the beach. (Yes, heavy traffic dictates lots of one-way streets, and if you want to drive along the water on this stretch of the coast you have to be heading south.) I passed a four-story Bauhaus block at HaYarkon 96. It was U-shaped, and the ends of the arms were rounded, so from the street the building suggested a pair of whales breasting their way to the sea.

The building had been built for Karol Reisfeld, another immigrant who had landed penniless in Palestine in 1933. Twenty years later, he and his wife owned an engineering company, some citrus groves, and at least this one apartment building. They were childless and in 1966 willed the building to the Hebrew University.

When I saw it, the building had recently acquired a nine-story glass and metal addition as black as death and looming behind the original building. I asked the doorman about the shutters on the original wings. They were lowered on every floor. I figured I knew the answer, and I was right. He explained, “The owners are not here. They live abroad and are very rich. Not like me.” He showed me an old photo from the days when the balconies had overlooked the beach. The construction of a Dan Hotel in 1953 blocked the view, which means that buyers in the last seventy years have known they wouldn’t see water. Maybe the idea of being close to it was enough. That, plus having a foot in the land of Israel.

That would have been a comfort. I once spent an unnerving hour at the Maidanek extermination camp. It’s on the east side of Lublin, a Polish town about fifty miles from the Ukraine border. There were no crowds. A dome as large as the one over a full-sized merry-go-round sheltered a mountain of what looked like ash from a thousand wood stoves. Nearby, the interior of a barracks had been subdivided by wire mesh into compartments with thousands of pairs of children’s shoes sorted by size, toddlers and up. Perhaps because there were so few other people around, I found this camp more sinister than Auschwitz and Birkenau. That’s what happens to places with millions of visitors: you can’t help thinking about the places more as they are than as they were.

Or I recall the old Jewish cemetery in Krakow. The tombstones were so tightly jammed together that as I walked between them—sometimes unavoidably walking on them—I imagined hands reaching up to grab an ankle. Several generations of living in Israel may have left Israelis immune to such shivers, but I’ll bet that the foreign buyers of luxury apartments in Tel Aviv aren’t. They may have escaped the charnel house, but they haven’t joined the reconstituted Jewish nation. They’re still adrift.

Tired of Bauhaus monotony, I walked south until I bumped into Neve Tzedek. This is the neighborhood that was begun in 1887 by the first Jews to move outside Jaffa, and it’s startlingly visible on satellite views where, stuck between the south end of Rothschild Avenue and the sea, it shows up as an island of red roofs. The red is clay tiles on pitched roofs, which are a Class A felony under Bauhaus law.

Many of the houses in Neve Tzedek look as though they’ve been airlifted from Old Europe. Some are decrepit, but others have been elaborately renovated. At the corner of Barnet and Amzaleg, I passed a wall that looked like a ruin, roughly patched, missing large stone blocks, and braced by iron tie-rods. A porthole high up revealed a disc of blue sky. Perhaps it was the heavy double doors, studded with bolts and freshly stained, that made me wonder. Perhaps I pulled on a shutter. I don’t remember, but I have a picture of the inside, where rustic walls enclosed a new wooden deck leading to new flagstones around an infinity pool and a flanking lawn with an oscillating sprinkler. Talk about the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. There’s no River Nile in Israel; there’s only the Sea of Galilee, an aquifer, and desalination. The women of Pinsker 23 would not have believed their eyes.

The Neve Tzedek Tower rose in the distance. The name comes from Jeremiah, chapter 50, and the King James translation is “habitation of justice.” Jeremiah’s “habitation” is not a place, however, it is God himself, so the Neve Tzedek Tower, taken literally, is God’s Tower. It’s a forty-four-story residential building, and it was completed in 2007. Airbnb has listings, and some of the three hundred units are always for sale. Were there objections when construction began? Of course there were, as there would be anywhere when a high rise is proposed for a neighborhood of single-family homes, but as a local resident told a reporter, “When the municipality and a businessman hook up, there is no power on earth that can stop them.” I probably don’t have to tell you again to bet on the money.

I hadn’t come all this way to see money murder an idea, so I drove up to Jerusalem. I thought I knew my way around, because in the 1990s I had spent three summers in a village downhill from Bethlehem, but for some reason I put myself this day in the hands of Lady Google, who directed me to Jerusalem’s Old City by a circuitous path that perhaps made sense but took me through nondescript industrial neighborhoods guaranteed to discourage all pilgrims.

I managed to park close to Jerusalem’s old railway station, now an entertainment venue. The station is about half a mile west of the southwest corner of the Old City, which is roughly square and wrapped by a wall about forty feet high and half a mile long on each side. The walk from the railroad station to the Old City drops down into the Hinnom Valley and then climbs up about a hundred feet to the southwest corner of the city wall. It’s a small miracle on that walk—down, across, and up: about fourteen hundred feet of the western side of the Old City’s wall is on display, stretching from the wall’s southwest corner north to the Jaffa Gate, which is about midway along the western side of the Old City.

I call it a small miracle because the wall might have been destroyed as the city expanded during the twentieth century. It now reaches some three miles beyond the walls, but soon after occupying the city during World War I the British created a narrow green belt around the Old City. The belt is not very green—Jerusalem has a bit more annual precipitation than Madrid—but the law succeeded in prohibiting the construction of buildings touching the wall. Israelis have few fond memories of the British Mandate in Palestine, which lasted until 1948, but with regard to the preservation of the Old City they are in Britain’s debt. So was I on this afternoon, warm for January. The sky was clear, and the wall’s stone blocks—on the tan-to-rust color spectrum—were warm to the touch.

The Old City of Jerusalem is, like Tel Aviv’s White City, another UNESCO World Heritage site. It could hardly not be one, given its cultural importance, but the city is fundamentally a European import. The Romans, after all, destroyed the city of David in about A.D. 70. They then rebuilt it as a typical Roman colony, with a square footprint, cardinal orientation, axial east-west and north-south streets, and a set of infilling parallels creating a grid within the square.

Again, I am not objecting to the UNESCO listing. Cities built on a Roman plan are as much a part of the world’s heritage as slaughterhouses and lead smelters, and there aren’t many Roman cities as well-preserved as Jerusalem. Trier and Merida, the oldest surviving Roman cities in Germany and Spain, are both UNESCO sites, and neither of them displays the Roman form as clearly as Jerusalem does.

Still, getting Jerusalem on the List was tricky. Article Four of the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage—that name must have been contrived by someone for whom English was a fourth language—Article Four, as I say, specifies that nominations can come only from a “State Party” that has signed the Convention and which is nominating a location “situated on its territory….”

At a 1981 meeting in Paris of UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee, Israel was told that it could not speak because it had not signed the Convention. It would not do so until 1999, almost twenty years later. Jordan had signed the Convention but–here’s the catch–had lost control of the Old City in 1967, during the Six-Day War. If the committee had been evenhanded, Jordan, too, would have been told it could not speak, but the committee had already allowed Jordan to nominate the Old City, and so it perhaps felt compelled to allow Jordan’s representative to support the nomination.

Jordan’s ambassador to France, himself a Palestinian, assured the committee that Jordan was “not using this Committee or your deliberations as a vehicle for political claims.” This made no difference to Ralph Slatyer, Australia’s representative. He said that the nomination should have been “accompanied by a declaration stating that inscription carried no explicit or implicit endorsement of any claim to sovereignty.”

The American delegate, David Rowe, was blunter. He assured the committee that he recognized the “universal cultural and historical value of Jerusalem,” and he spoke of “the high esteem of the U.S. delegation… for the distinguished Jordanian delegation.” Still, he said, approval would be “a failure to adhere to the articles and provision of the World Heritage Convention.” He was right, of course, but he had only one vote, and the committee voted in favor of the listing by fourteen to one with five abstentions, including Australia’s. The official record of the meeting includes this statement: “The U.S. delegation regrets the result of this extraordinary session and asks that the record reveal our full disassociation from its outcome.”

I don’t want to get into the sorry details about the United States and its relationship with UNESCO. The good news is that Jerusalem doesn’t care. The top half of the city’s old wall dates from about 1540, when Suleiman the Magnificent ordered the reconstruction of what was then mostly in ruins. The more interesting part of the wall is the lower half, which is made of much bigger blocks that seem to grow from the horizontally bedded natural rock. This lower half was built by order of Herod. He fares badly in the Bible but built walls that will outlast anything built today except possibly vaults for nuclear weapons and waste.

The Jaffa Gate, midway along the Western side of the wall, is also at the western end of the city’s axial east-west street, called David Street because the Crusaders believed, incorrectly, that King David’s palace fronted on it. The street is no more than a pedestrian lane paved with stone, and it extends east about a thousand feet to its crossing with the axial north-south street. Turn left here, and it’s less than a ten-minute walk north to the Damascus Gate. Continue straight on David Street past the intersection and in a thousand feet you bump into the walled precinct that Genesis calls Mount Moriah. In modern Hebrew it’s Har Habayit. Muslims call it the Haram esh-Sharif or “Noble Enclosure,” and for English-speaking foreigners, like me, it’s the Temple Mount, a name referring to Solomon’s temple, destroyed by the Romans.

Whichever name you use, the walled precinct protects the Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock. Unlike Solomon’s temple, which is gone except perhaps for some flagstones, those two buildings are intact, though modified over the centuries. The Dome of the Rock, for example, is instantly recognizable today from its brilliant gold leaf but until 1960 was roofed with lead plates. They were replaced in the 1990s with an aluminum alloy, which was gilt a generation later.

Kaiser Wilhelm in 1898 rode through the Jaffa Gate on horseback. General Edmund Allenby a generation later entered on foot. Some people will dismiss Allenby’s dismounting as a stunt, but I think it was modesty. Jerusalem has a charismatic power over anyone who has ever respected Judaism, Christianity, or Islam, even if they have no religious faith.

I turned left before the central crossing and headed north to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, which is roughly at the center of the Old City’s northwest quarter. Just beyond the scarred and scraped wooden door to the church, I passed a young Filipina in a pink hoodie and an Orthodox grandmother in black, both kneeling to kiss the Stone of the Anointment, but it was a Sunday, and the church was ridiculously–dangerously–overcrowded.

The church had been destroyed in A.D. 1009 and was never rebuilt except for a rotunda marking the supposed burial place of Jesus. Because of the crowding, I left the church almost immediately and worked my way around several intervening buildings to find a patch of open ground rimmed by great arches and columns. These were the remnants of the destroyed church’snave, its space occupied now by a half dozen severely plain plastered brick buildings, windowless, roofed with dusty corrugated sheet metal, and fitted with padlocked doors. These buildings were controlled by the various sects sharing custody of the church, and they seemed in their poverty far closer to the heart of Christianity than the wealth commonly displayed in churches.

I went down to the Temple Mount, unchanged from what I remembered from twenty years earlier, except that people hoping to touch the Western or Wailing Wall now waited in long lines to pass through airport-style body scanners. A day later, I myself passed through those scanners. It was the only way to get up to the Temple Mount. (There are several other entrances, but Israeli police allow only Muslims to use them.) I then tried but failed to enter the Aqsa Mosque and Dome of the Rock. This was another change from the 1990s. I tell myself to stop complaining and let the Palestinians exercise the trifle of power that the Israelis allow them.

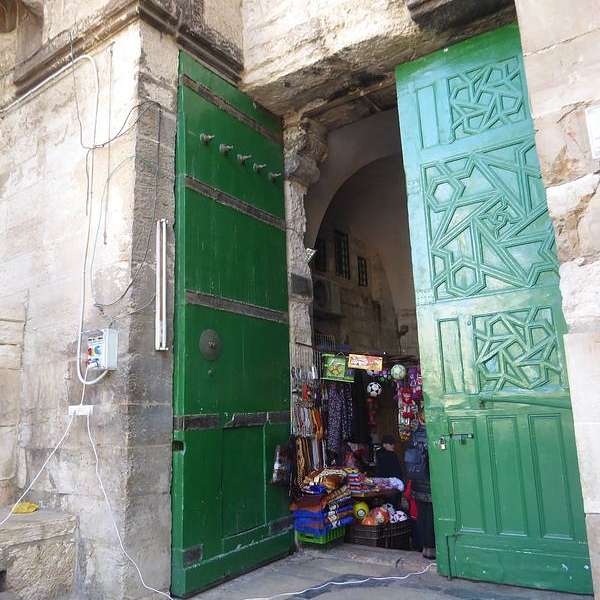

I wandered over to the deserted northwest corner of the enclosure, where Solomon’s temple was probably located. That’s when I noticed the double wooden doors leading west into the cotton market, the Suq el Qattanin. I had never paid attention to these doors, partly because Israeli police make sure that non-Muslims do not enter the Temple Mount this way, but each door is about twelve feet high, three feet wide, and several inches thick. Painted green and partly covered with a carved pattern of irregular polygons, they must weigh three hundred pounds each. The doors were open when I saw them, but what caught my eye was that they did not come to rest against the thick wall. Instead, they fitted into pockets in the wall.

Like the gold leaf on the Dome of the Rock, these doors weren’t old. Ronald Storrs, the first British governor of Jerusalem, wrote of the cotton market that “this fine mediaeval bazaar had degenerated through neglect into a public latrine. The shops were filled with ordure, the debris was sometimes lying five feet high, and the picturesque doors had been broken up for firewood by the Turks.” Storrs, who went on to unhappy postings on Cyprus and in Northern Rhodesia, wrote that “there are many positions of greater authority and renown within and without the British Empire, but in a sense that I cannot explain there is no promotion after Jerusalem.” That “sense I cannot explain” is what got Allenby to dismount at the Jaffa Gate.

As Jerusalem’s governor, Storrs hired Charles Ashbee, a British Arts and Crafts designer who renovated the market and replicated its doors. That wasn’t all. The Armenian genocide had brought the Red Cross to the Middle East, and Storrs wrote that Ashbee “bought the looms which the American Red Cross had set up for the relief of Armenian and Syrian weavers, and installed them in the ancient Cotton Market….” Since then, foreign competition has killed the Palestinian weaving business, and even the keffiyehs or checkered scarves worn by many Palestinian men come mostly from China. A few dealers elsewhere in the Old City still sell old thobes, the traditional black Palestinian dress fitted with bright chest panels or gabbehs, but I wondered what Storrs would make of the big plastic tubs I saw in the cotton market now. They were filled with penny candies.

Discouraging? I hadn’t seen discouraging until, returning to my car, I detoured to St. Andrew’s Memorial Church, dedicated by Allenby in 1927. A brass plate read, “To the Glory of God and the Undying Memory of the Officers and Men of the London Scottish Regiment who laid down their lives in the Palestine Campaign, 1917-1918.” Another plate, placed ten years laterby General Arthur Wauchope, high commissioner at the time, read: “In memory of the Black Watch Royal Highlanders who fell in Battle in Palestine, 1917-1918.”

Both plaques are customary and might even be dismissed as perfunctory, and so might the church itself, which has a barrel vault divided into segments by widely separated ribs. There is absolutely no ornamentation. In some more peaceful part of the world I might have said that this simplicity was an economy measure, but not here. Here the blank walls seemed to that life itself was pointless. Perhaps there are more radical thoughts to entertain in the Holy Land, but I can’t think of any.

Footnote.

I have cut this episode in half, at least for the time being, by removing sections that dealt with three sites near Jerusalem.

The first was Bethlehem, where I paid special attention to the recently-despoiled Solomon’s Pools and also to the so-called Separation Barrier, a concrete wall that should humiliate Israelis as much as it demeans Palestinians.

The second was Battir, for many years the archetypal Holy Land village, famous for its irrigation system and olive terraces but now a village of commuters whose gardens are mostly abandoned and who look upstream every day to see a Jerusalem that few if any may enter.

The third was the old city of Hebron, an intact Muslim city renovated with care in the 1990s and since then economically and demographically choked nearly to death.

All three places are on UNESCO’s World Heritage List, and all three are officially endangered.