Craftsmanship

Welcome to our podcast! Craftsmanship is a not-for-profit, multimedia magazine focusing on in-depth profiles of intriguing artisans and innovators across the globe — the movers and makers who are creating a world built to last. To support this project, please consider making a donation — it's tax-deductible! www.craftsmanship.net/donate

Craftsmanship

Shrine and the Art of Resilience

Pandemic, political strife, poverty, war. In times of extreme upheaval—global or personal—can the act of art-making ease suffering and strengthen resilience?

"Shrine and the Art of Resilience" originally appeared in the Summer 2022 issue of Craftsmanship Quarterly, a multimedia, online magazine about artisans, innovators, and the architecture of excellence. You'll find many more stories, videos, audio recordings, and other resources on our site — all free of charge and free of advertising.

Written by MELINDA MISURACA

Introduction by CHRIS EGUSA

Narrated by LINDSAY SCHERBARTH

Produced by CHRIS EGUSA

Music by MIKE SNOWDEN / BLUE DOT SESSIONS

Shrine and the Art of Resilience

Pandemic, political strife, poverty, war. In times of extreme upheaval—global or personal—can the act of art-making ease suffering and strengthen resilience?

The first time I met the outsider artist known as Shrine, he was leaving for Tanzania in an hour and hadn’t packed. It was late November of 2018, and we were sitting in his Pasadena, CA, backyard while he mused over what to cook for dinner—something with shiitake mushrooms, as he’d discovered some spores that he’d tossed in a corner of the garden had bloomed into a feast. “I have no idea what I’ll do when I get there,” he said of the impending trip. No idea where he’d go once he landed, nor who he would talk to, where he would sleep. The only plan was to decorate Ujasiri House, part of a children’s cancer hospital in Dar Es Salaam, a project loosely arranged through a friend-of-a-friend. Where he’d get paint, brushes, and a ladder, who knew? Scaffolding? Shrine seemed to relish the uncertainty.

We strolled through his garden, a kaleidoscopic display of pop-bottle towers, bottle-cap garlands, and tropical foliage. “Self-expression is a wild thing, with a life of its own,” he said. “You steer it somehow, but you also hang on and see where it’s going. You have to be open, trust your intuition.”

Weeks later, Shrine told me the Tanzania trip had been a success. He laughed about the slapped-together bamboo scaffolding and the ones responsible for moving it around—“elusive, slippery, evaporating ghost-men”—who’d disappear for days, time that Shrine filled by making art with young cancer patients. Photos of the freshly painted, cinder-block hospital popped with joyful colors and patterns.

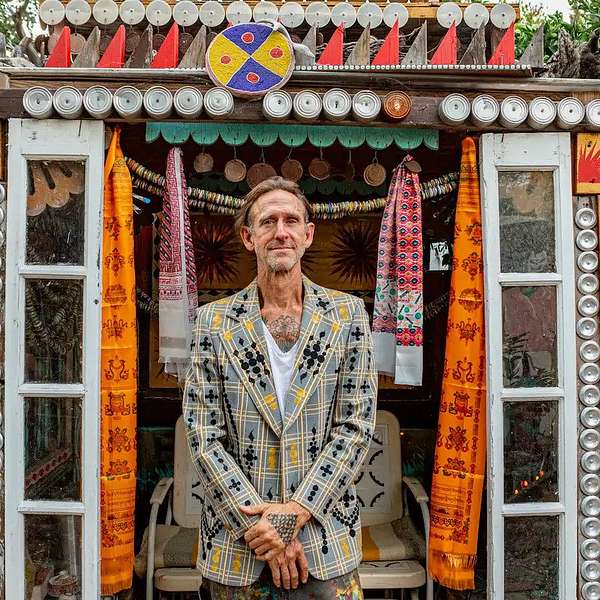

A native Angeleno in his late 50s, Shrine (a moniker bequeathed during the earliest days of Burning Man) was born Brent Allen Spears and raised by his two “grammies,” once it became clear his parents “weren’t equipped for the job.” His work adorns buildings all over California, like the Craft Contemporary museum and La Luz de Jesus Gallery, both in L.A., and San Francisco’s Odd Job Bar, as well as others in Denver, Chicago, New York, Mexico City, Quito, Cape Town, and elsewhere. But for the past several years, Shrine has sloughed off festivals, large commissions, and posh gallery shows. “It doesn’t interest me anymore,” he said when I asked about the swerve. “As a culture, we Americans are overstuffed and over-entertained. Art hardly matters. We see it, we move on, we forget about it.” Instead, Shrine volunteers his time to make art in inner-city housing projects, war-ravaged neighborhoods, and refugee camps.

“I enjoy redefining the trashed, bombed-out, and discarded with displaced people who have nowhere to go, those who’ve dealt with a lot of trauma, or whom others called ‘refugees,’” he told me. “I relate to people with nothing to do but survive and heal, nothing to carry but potential.”

This revelation didn’t surprise me. In our conversations over the months, Shrine recounted his own struggles: the extreme violence and neglect he’d suffered as a child; a near-fatal accident that took years of recovery.

“The world is awash in fear,” he says. “We’re all being bombarded with toxicity in our air, food, and water, combined with a nonstop assault of toxic ideas. In each moment we have a choice, to choose between love or fear. Expansion or contraction. To make something is an act of expansion. It gives you something to care about. Inspiration keeps you out of the hospital.”

To cover his bills and fund his trips, Shrine still accepts some commissions, but gives much of his time away. He travels on the cheap, staying with people he meets, occasionally sleeping on floors. His formula is simple: He shows up with brushes and buckets of paint, and offers his services, free of charge. He’ll paint anybody’s home, stairway, outhouse, abandoned car, shoes, flattened plastic water bottles, what-have-you—bringing no hidden agenda, “No trying to save anybody from anything,” he says. Just art.

“I’m not a carpenter, I’m not a plumber. I can’t help people with their urgent physical needs,” he says. “But I can share what I’ve learned of the craft of making lines, shapes, and colors.”

Studies have shown that various forms of art therapy can be healing for the severely traumatized, yet many of the folks Shrine meets on his art-making forays have never seen color-in-a-can, or a painted wall. Their excitement bubbles over when he begins to decorate a modest shelter that has never seen a lick of pigment. “It blows their minds,” he says. “People can’t figure out exactly why I’m there.”

Everyone is welcome to watch Shrine work, or join in to paint a burned-out vehicle, an abandoned train car, a communal oven. His only rule: You must commit to the project. “When you pick up a brush and start painting, it can be exhilarating,” he says. “And contagious.” In the summer of 2018, in the Nakivale Refugee Settlement near Kampala, Uganda, Shrine and camp residents decorated simple shelters and storefronts, made trash art with puckish poses of kids, and created a space where people banged up by war might begin to reimagine their post-trauma lives.

I tagged along on one of Shrine’s local commissions to decorate a San Francisco tattoo parlor. It was almost trance-inducing to watch him deftly brushstroke rows of swishes, swashes, and swags, his movements elegant and dance-like. Shrine is fond of old typography symbols—the tildes, asterisks, lozenges, and chevrons common in turn-of-the-century handbills. In his hands, these symbols are repurposed in vivid colors and infused with a sense of symmetry and balance knocked a little off-kilter, like a dapper old gentleman strolling a lane in a pinstriped suit, humming to himself while listing slightly to one side.

Shrine has fired up dozens of seat-of-his-pants art projects in Nepal, Mexico, Nicaragua, Senegal, Uganda, Kenya, Haiti, Lebanon, and elsewhere, these unofficial gigs often spawning offshoot collaborations, like the African Leadership College Painting Club in Mauritius, its mural wall repainted monthly by volunteers, or an art center for war-traumatized kids in Nakivale.

News of Shrine’s impromptu art happenings gets around. He once deplaned at a tiny Senegalese airport and “the next thing you know I was up on a ladder, painting the entrance.” His Instagram dispatches reach more than 30,000 followers, many responding with hearts, prayer-hand emojis, and donations toward future trips. But behind the playful flourishes is a man who readily admits that self-expression is the only thing keeping him from being quote “buried in the marsh” of his own dark thoughts. On some days, he sinks under anyway.

“There were moments when I told myself that none of this is going to do shit,” Shrine said, of a 2019 painting stint in the Kyebando ghetto near Kampala, Uganda. “Everywhere you look, people are suffering. They have no money, no permanent home. They’re sick with diseases. They’re totally fucked. As a species, we’re all totally fucked. What’s the point?”

The point is eloquently made by others, like William Butala, a Congolese refugee and self-taught art teacher now living in the Nakivale Settlement. “Before I met Shrine, I lived in fear of expressing myself in the society where I now live,” he wrote to me via email. “I had nothing, no possibilities. I wanted to teach art to children, but I didn’t know what I was doing. One night Shrine said to me, ‘Feel the freedom to take right actions, let your heart express itself, and glow with light to inspire others.’ My life changed with this one phrase.”

Over the past couple of years, Shrine has collaborated with the Great Oven project in Lebanon to teach former child-fighters to cook and make art. The Great Oven crew and local volunteers build and decorate communal ovens, cook and share large neighborhood meals, and create community spaces that take on a life of their own. With another local organization, MARCH Lebanon, Great Oven helped negotiate an agreement between two warring Tripoli neighborhoods to paint a peace-themed staircase that marks the boundary between them.

“Shrine has inspired people to become artists in one of the hardest places on Earth,” Great Oven’s co-creator James Thompson told me. “He’s motivated to put art in places where there isn’t any, like a mural wall on the frontline of a war, or an art studio in a former sniper’s perch.”

When I spoke with Shrine recently, he revealed that since we’d last talked, his son Dylan had taken his own life. Dylan left behind a room that still carries his scent, and is filled with thousands of his drawings.

“Dylan had a long, excessive, fully realized, sometimes tumultuous, often joyful creative practice that enriched his life greatly, even if it didn’t save him,” said Shrine. “His death doesn’t mean his self-expression was a failure.”

I asked how he was coping with the shock and heartbreak. “Right now, I’m going through his drawings and sharing them,” he said. “It’s how I can celebrate Dylan’s life. That, and I show up and paint.”