Imagination State

Welcome to Imagination State, with Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer. This is a podcast about imagination: how it shapes our lives, our world, and our futures. You’ll hear from people on the frontlines of imagination: artists, writers, thinkers, activists - teachers of all kinds - who stand up to the forces that shrink our inner worlds, who open us to richer, more just futures, and who remind us that building imagination is also a form of liberation.

Imagination State

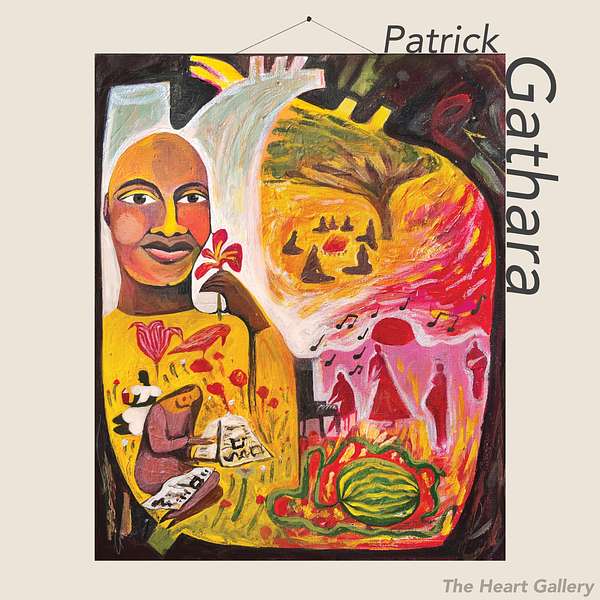

Inclusive storytelling from Gaza and beyond with Patrick Gathara - Part 1

For the first episode of The Heart Gallery Season 2, I talk to Patrick Gathara, The New Humanitarian's Senior Editor of Inclusive Storytelling. Patrick talks about what inclusive storytelling look like in a context where the news is changing by the minute, where echo chambers are swirling with recycled talking points, where mainstream media is saturated with dehumanization of whole groups of people, and all while a literal genocide on the people of Gaza is being carried out. We also discuss the state of inclusive journalism and the storytelling elsewhere in the world: what is going well, where we're falling short, and what we should demand more - and less - of from our media.

Part 2 will be uploaded on Monday, Nov 13. Episode blog post will be up then as well.

Links:

- Patrick on Twitter

- The New Humanitarian

- The Heart Gallery Instagram

- The Heart Gallery website

- Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer Instagram

Credits:

Samuel Cunningham for podcast editing, Cosmo Sheldrake for use of his song Pelicans We, podcast art by me, Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer.

Intro:

Welcome back to The Heart Gallery Podcast, where we discuss art against a backdrop of social and global issues, I am the creator and host, Rebeka Ryvola de Kremer. This is episode 1 of The Heart Gallery Season TWO. I originally had another episode lined up to launch the season, and was planning to launch in January 2024,, but when I got a chance to connect with today;s guest, I knew I had to use to use this conversation to launch the season.

Today I’m sharing the first segment of the conversation I had with Patrick Gathara. Patrick is Senior Editor for Inclusive Storytelling at The New Humanitarian, a distinguished voice in the realm of journalism in his own right, and also a cartoonist.

In this episode, Patrick talks about inclusive storytelling in the coverage of the devastating ongoing situation in Gaza . inclusive storytelling not only to gives voice to the marginalized, but also invites more creative ways of telling stories to get at their fuller complexity. What does inclusive storytelling look like in a context where the news is changing by the minute, where echo chambers are swirling with recycled talking points, where mainstream media is saturated with dehumanization of whole groups of people, and all while a literal genocide on the people of Gaza is being carried out.?

We also discuss the dangerous reporting trend of pervasive 'othering' that exists elsewhere as well - that seems to exist everywhere in fact - and that often distorts complex narratives and threatens to put our very humanity in peril. He invites us to see and question the single story, to resist the seductive simplicity of us-versus-them, black vs white mainstream reporting, and to seek out stories, poetry, and other art that can help us actively create multifaceted tapestries of world understanding.

In a media landscape where we can get lost in tangled mess of soundbite storytelling, Patrick runs in the other direction and makes a compelling case for us to join him. I hope you’ll be as thrilled to hear Patrick’s perspectives as I was and please do look for the second part of this conversation.

[Music]

Rebeka (02:45.546)

Patrick, I am so incredibly thrilled to be talking to you today. I've been following your work for, I'd say a couple months, a few months is when I heard you speak for the first time. A couple months ago on the New Humanitarian podcast, you were talking about inclusive storytelling and also with the definition of humanitarianism. Super fascinating. And I want us to get into that.

And I reached out to you right away to see if you'd be willing to talk to me. And unfortunately, since that time when I first reached out to you, we have seen just horror be unleashed on the Gazan people following the October 7 attacks on Israelis by Hamas. And I know that you have been writing about this and you've been active on social media about this. And I am hoping we can talk a lot about this today. I do hope that we can also chat about some of your other work, some of the other inclusive storytelling efforts from the New Humanitarian as well. So let's just see how it goes. But to start, could you just say hello and let us know what is inclusive storytelling?

Patrick Gathara (03:56.356)

Okay, hi, my name is Patrick Gathara, as Rebeka said, and thanks for having me on the podcast. I work as the senior editor for inclusive storytelling at The New Humanitarian, which is one of the few only newsrooms in the world that actually focuses on humanitarian stories and humanitarian crisis and telling stories out of that.

So what is inclusive storytelling? Inclusive storytelling is essentially trying to ensure that the perspectives of the people we report about included in the stories that we tell, in the narratives that we bring to the public. So it's very much really along the lines of what people call decolonized reporting, where we are moving away from kind of a Western centric telling of the world, away from essentially parachuting into crisis and sort of talking over people's heads, describing their reality for them to other audiences to a model where it is really taking local perspectives and including them in stories and also considering the local people as your audience. It's no longer the model of essentially reporting exotic happenings far away to an audience back home. It's really talking to people about their reality and acknowledging that they will be an audience, they will hear what you're saying and that it's got to reflect what life and what crisis look like from their own perspectives.

Rebeka (06:06.838)

How did you get into it yourself? What is your first involvement with inclusive storytelling? Is it the cartooning?

Patrick Gathara (06:12.696)

Well, I mean, I've been a cartoonist for a long time. I think I started cartooning when I was in the turn of the millennium. So I've been doing it for like, well over 20 years. And I think it does give you a perspective, although I wouldn't say it's necessarily inclusive, it's very opinionated as an art form, especiallypolitical cartooning or editorial cartooning, which is what I was doing and I still do at the time and again. But I think for me, it's really been a journey that was sparked by just thinking about how events in Kenya, where I'm from, I'm right now in Nairobi, is reported in the world and how it is seen in the world.

and the sorts of narratives that go out. And I think also it's even within Kenya, we shouldn't really sort of portray these as, you know, solely a problem of how the West reports on us. It's really how we report on ourselves, how we sort of, we find stories being written by people in the city, about people in the rural areas, you know, and stuff. So it's to really, I started to think about how that...

impacts how we understand these spaces, how we understand other people, how we can other them, how we can, in a sense, dehumanize them, fail to see them completely as human beings the same way we are. And I think for me, that's really what got me looking at ethics, in essence, within the

journalism and writing about that in my columns, and tried to point out some of the things that I thought could be done better. I studied a bit of it when I was doing my master's at the Akakand University. And it's really been since then, sort of building up on what I learned. I mean, one of the interesting things.

Patrick Gathara (08:32.496)

when I did my thesis was on the use of graphic or gory images in Kenyan media. You know, and as part of that, you know, one of really surprising findings for me was just how similar it was when Kenyans report on other people, how they reflect very much the same things that they complain about or how they are.

reported on and I think it kind of showed to me that this is really a problem with how we understand journalism and some of the ethics that are embedded in there and how we have learned to practice it. And that we probably need to rethink some of this, some of the standards that we aspire to.

you know, so that then we can be more inclusive, we can do a better job and a more accurate job of explaining the world to others.

Rebeka (09:37.591)

Can you think of one of the earlier examples of where you saw an alternative to that kind of reporting?

Patrick Gathara (09:45.016)

Well, I mean, I think for me, it's I mean, I started looking at humanitarian reporting a few years back. And especially when you think about how countries, in fact, I shouldn't say humanitarian reporting, I should say foreign reporting. And when you think about how countries are described, I mean, from about 2016, I started running sort of these Twitter threads or

describing what's happening in the West in the same way I thought it would be described if it was happening here, you know, so using the same language, the same adjectives, you know, and stuff. And it, that for me was really eye-opening. I mean, obviously, when I started it off, I thought it would be sort of like a fun thing to do, you know. But as

Patrick Gathara (10:42.104)

I got an understanding that it's a whole language that is created to describe certain places. And it's never applied outside of these spaces. And that's kind of what is funny about it when you kind of flip the narrative. And I was thinking that, why is it that? Why do we accept that? Why is the world ordered in this way? And I think, obviously, what you think about things like Brexit in the UK, the rise of

Trump in the US. I mean, they make these things, I think, much more glaring, the differences in how things are presented, you know, what constitutes, for example, a rigged election, you know, in the US you'll be told, oh, elections are gerrymandered, or there is some voter suppression, but they're not really rigged. You know, if that happened in Kenya, we'd be calling it rigging, that's stealing an election.

You know, clearly. And so I got to thinking about how these terms are utilized and how they create this bifurcated view of the world. As you know, there's some places where they've kind of figured everything out, it all works and stuff. And to borrow Trump's phrase, there's some third world shit holes where nothing works. You know, so it's really, I think for me, challenging.

those sorts of perceptions, those sorts of stereotypes that I think are really, well, they do include some elements of truth, really present a very one-sided, a very black and white picture of a world that is actually much grayer than I think a lot of us would want to accept.

Rebeka (12:29.874)

And you work at the New Humanitarian. You're the senior editor of inclusive storytelling. And I wonder if you could share a little bit about the history of the New Humanitarian and how it has developed its own inclusive storytelling. Like whether it was falling prey to some of that two-sided messaging when it was first created and maybe how it has started to go in a more equitable direction.

Patrick Gathara (12:54.88)

Yeah, I mean, I just joined the New Humanitarian in May of this year. So I have been there for a whole long time. But if you look at its history, it was really, in a sense, created to deal with an absence of knowledge. It was created in the aftermath of the Rwanda genocide.

was meant to be a resource for humanitarian groups, humanitarian agencies and workers about the dynamics and politics and goings on within crisis so that people who want to help then have a better idea of what's happening in the ground or they don't end up

making a situation worse, that when they go in, they know where to position themselves and what to expect. It was formed as part of the UN or was funded by the UN under the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and was at the time called the Integrated Regional Information Network or IRIN.

you know, and really grew to be a huge, very large news organizations or news gathering operation. You know, they had TV stations, radio programs that they were putting out. They were doing lots of text stuff and were based here in Nairobi, you know. And

They got spun off from Orchard in, I think it was 2014, and rebranded as the New Humanitarian. Now, I mean, they were basically rebuilding from scratch from 2014, and rebranded as the New Humanitarian. So they've always had a sense in which they are trying to explain things to largely the humanitarian sector.

Patrick Gathara (15:22.196)

about crisis that were not present in everyday media reporting. So in that sense, kind of decolonization is in their DNA. But of course, like all news organizations, they have their misses and plasmids in their strategy. That was passed in 2019. The five-year strategy, one of the...

main pillars for that was decolonized reporting. Actually, it was passed in 2021. I've got to confirm the date. But one of the main pillars of that is decolonized reporting. And now it's to go beyond simply reporting for international audiences, for largely Western-based humanitarian agencies, to include the people that we serve, the people on whom we report.

as part of our audience, as consumers, but also as producers of the news. So it's looking beyond simply talking about them, but actually giving them the platform to talk about themselves. How do we include their own, not just their own stories, but also their own ways of telling stories, their own formats.

Patrick Gathara (16:50.488)

hopefully reflects when the stories told reflects their perspectives, their priorities and people who want to come in and help do not simply see them as victims but also as agents. One of the things that I think really surprised me when I got into this, looking into humanitarianism is just how misrepresented crises are.

you know, people's ideas of crisis and who is helping, you know. So we've got, like there was a study done in 2019 by ODI that shows that international humanitarian aid is, accounts for only something like 2% of resources that people even in the worst crisis get. But you see everybody when you ask them, you know, who helps in a crisis, most times the...

the image that comes to mind is the foreign aid worker. But if he only represents 2% of what people are getting, you've got to ask, then why is that the case? And I think it comes from the perspectives that we have in what journalists are taught, in how journalists are kind of conditioned to repong on crisis. It's not...

coincidence that they'll fly into somewhere like Northeast Kenya or somewhere like Ethiopia and interview a few white aid workers. When they need an expert, they get a Western expert and stuff. So it's always reporting about people rather than letting the people speak for themselves and giving them the platform. So I think for TNH that has become a real main pillar for that and kind of was hired to...

help them, I mean to lead that effort and to help them figure out, you know, how do we actually improve what we put out so that it's actually useful, not just to the humanitarian sector but also to the people we report on.

Rebeka (18:59.458)

How's it going? How's it going? I know you've only been there for a few months and now we have the genocide in Gaza going on 30 days. And I'm curious how it's been going for you personally and also... Oh, I'm sorry. Can you hear me now?

Patrick Gathara (19:12.664)

I'm sorry, I can't hear you very clearly.

Patrick Gathara (19:17.433)

Yes, not good.

Rebeka (19:18.782)

Okay, perfect. I'll be a little closer. Yeah, I'll just repeat the question. I'm wondering how it's going for you. You've only been at the New Humanitarian for a few months, and the last month of that has been with this genocide happening in Gaza, now going on 30 days. And I'm wondering, so how is it going for you personally, and what do you see being done well in the realm of inclusive storytelling with what's going on in Israel and Palestine specifically?

Patrick Gathara (19:47.332)

Well, I think with regard to what's happening in Gaza and Israel, I think that has really highlighted some of the problems that we have with how places where crisis happens are reported on. So if you look across social media, there's been a lot of criticism about how especially Western media, as we understand Western media.

is portraying the crisis, about the perspectives that are brought in, about who dies and who is killed, you know, the language that is used, the sort of acceptance almost, that the death of Palestinians is somehow acceptable, you know, in a way the death of Israelis is not.

You know, the New Humanitarian has put out an editorial on this, discussing how media is failing to represent a crisis in a way that humanizes the victims, all the victims. And I think it points to a basic failure of journalism ethics, you know, and the need to rethink.

you know, ethics that were created essentially for a different age, for an age when reporters essentially reported to their own audiences back home, you know, where it wasn't really expected that the people they were reporting about would necessarily engage with the content, with how they were being portrayed, or would actually be able to push back on it.

I think one of the big pluses, if we can say that on this, has been the ability of people within Gaza and Palestinians in general to be able to counter the narratives. I think this shows the power of social media, is that people can actually see what's being said about them and respond and actually be able to highlight.

Patrick Gathara (22:02.988)

you know, some of these problems. I think without that, we'd just be stuck with the one narrative with, you know, the privilege stories, you know, coming from the Israeli side. So it's for me a real lesson in why it is we need to rethink how we do as journalists, how we do our work. I think it's been really surprising to me

even after a month of these being pointed out, you know, throughout, that it's taking, I mean, it seems almost like there's a blind spot amongst lots of Western media that they are not actually seeing what's being pointed out. That's why I think it's an ethical failing. It's a gap.

in how, it's a blind spot, in how we conceive of the ethics. So the insistence, for example, on, you have to condemn Hamas, but nobody asks, well, do you condemn what Israel is doing? It never occurs to them to say that. Exactly, all the time. Right, yeah, exactly, even though it keeps being pointed out. So I think...

Rebeka (23:20.21)

Even though it's been pointed out, like you see it pointed out and like people gloss over it and then they go in the anti-semitism direction, right?

Patrick Gathara (23:30.144)

I mean, it's easy for people to simply say, oh, no, these are just racist reporters. You know, these are just people who don't care for Palestinians. But I think it's more than that. It's not. I think that's the easy way to see it. I like to think that these are reporters who are trying to do the job as best as they can. But they have these cultural and ethical blind spots that they are not aware of. They have not been made.

Rebeka (23:35.393)

Yeah.

Patrick Gathara (23:59.644)

are aware of by their training, by the editors, the entire ecosystem of news production. And until we are able to articulate a media ethic that says it's not just that you're reporting to that audience that you're used to, that we live in a world where everybody can see what you're saying.

Rebeka (24:01.047)

Hmm.

Patrick Gathara (24:26.536)

you know, and how do you understand your ethical obligations, you know, not just to the audience you're thinking, but to the people you're portraying, you know, to somebody else who might see this, you know, who you might not be conceiving as the audience. How do you understand your obligations to them, you know, and how do you navigate a world where people might have extremely differing expectations of what a journalist should do, you know, and how a

All this, if you look at the work of academics on global media ethics, one of the things they all agree on is basically we don't have a model for this. You know, we're still working in a world where journalists think in terms of very well-defined audiences, you know. It's only the guys who buy my newspaper or, you know, it's only the guys who listen to my radio.

But this is all being gated by other people. So people will take your newspaper, take a photograph, send it out on WhatsApp. I'll give you an example from my research into graphic images. The New York Times in 2019 had done a story on the terror attack here in Nairobi, the 262 attack.

and they had published an image of sort of two bodies slammed over a coffee table, you know. And they got a lot of blowback from Kenya. So when I was asking them about the decision-making that went into this, the interesting thing that came to me is the Kenyans constituted less than 1% of 1% of their subscribers. It never occurred to them.

that you know actually can just read what we do or that they would have even the ability to push back. It was a complete blind spot to them. They were thinking of this as Americans reporting to an American audience and well the Americans wouldn't be too bothered by this. So I think

Rebeka (26:34.111)

Yeah.

Patrick Gathara (26:47.216)

For coverage of Gaza, it's really important for people, for editors to start and journalists to start thinking about how they need to change their ideas of who audience is, you know, their ideas of what their obligations are, you know. As we start seeing the world has changed, the ethics that you had before are no longer fit for purpose.

How do we then move from here to a point where we start actually talking about a new media ethic for a globalized world, for globalized audiences, for globalized producers? Is that even possible? You know, and if it is, you know.

Rebeka (27:28.906)

Yeah, that was my question. That's my question, right? Because one of the top rules of storytelling is that you need to know your audience and that your audience, you need to be ideally communicating to one person, right? Like a very narrow, and then within that, people can find relevance and resonance to their own lives, to their own context. And so I'm so curious hearing you give this Kenya example, what does that look like? Or just more generally, how do we start to rebuild?

Patrick Gathara (27:44.166)

Right.

Patrick Gathara (27:49.261)

Uh huh.

Patrick Gathara (28:00.4)

Well, I mean, there's different perspectives as to one, whether it's possible. Most people think, I mean, lots of academics I've read say that you probably end up with a very fractured media system where you've got sort of very many diverse voices, you know, and very many diverse journalism practices, you know, and maybe the point.

in that sense would be, you know, how do we accommodate this plurality, you know. But others say, well, actually there might be a way to, for us to find sort of common understandings, or common ideas about how journalism should be done that would then stretch out across all of these various different ways of doing journalism. And the bottom thing for me is that we have...

Rebeka (28:56.075)

Yeah.

Patrick Gathara (28:59.088)

for a long time been, I guess, fed the idea that there's only one way of doing it, and that's the Western way. This is how we have developed it. So ideas like objectivity, you know, fact-based, you know, all of that. I'm not saying they are wrong, but I'm saying that they are for question, that there are other storytelling traditions, other journalism traditions that...

emphasis on different things, on things like humanity. You know, the idea that the storyteller is divorced from the story that he's telling, you know, is questioned, you know, and do you really have objectivity? Everybody comes to this with their own lens, with their own biases, you know. So it's to take all of these questions and to see what we can save their size from.

Rebeka (29:40.384)

Yeah.

Patrick Gathara (29:55.728)

The important thing isn't what we end up with, you know, is that we actually have the discussion, is that we actually start going towards something, we are deliberate and intentional about it. The ethics we have today, the media ethics we have today, developed over a very long period, you know. And we can't just assume that, you know, it is, you know, good for all time.

You know, and we need to come back and see where it feels, acknowledge where it feels, and have a conversation about how things need, how we need to accommodate the new realities. And at the New Humanity, that's sort of the conversation we want to lead. We want to be part of, we want to discuss, we want to say, this is what we are doing. This is what we are trying out. Who else is involved, who else is engaged? And invite them, you know, along so we can have a chat.

and see whether it's academics, whether it is practitioners, whether it is audiences. And let them see this is where we would like journalism to go or this is what we think should happen. And hopefully from there we can start synthesizing a new way of doing global reporting for a globalized world.

[Music]

Thank you for joining us for the first part of our conversation with Patrick Gathara.. Be sure to tune in for the second part of this discussion, where we'll continue to explore the power of story and journalistic arts and the role they play in shaping our understanding of global crises and the human condition.

Thank you to Samuel Cunningham for editing this podcast and to Cosmo Sheldrake for the episode music, which comes from his song, Pelicans We. The podcast art is created by me. Find links for connecting in the show description, along with ways to find Patrick’s work.

Until next time, take care.