Mystical Theology: Introducing the Theology and Spiritual Life of the Orthodox Church

“Mystical Theology: Introducing the Theology and Spiritual Life of the Orthodox Church”, with Prof. Christopher Veniamin

Mystical Theology: Introducing the Theology and Spiritual Life of the Orthodox Church, with particular reference to the Holy Bible and the witness of the Church Fathers, past and present. Available Units thus far:

Unit 1: Introduction: Holy Scripture, Greek Philosophy, Philo of Alexandria (Season 3)

Unit 2: Irenaeus of Lyons (Season 3)

Unit 3: Clement the Alexandrian (Season 3)

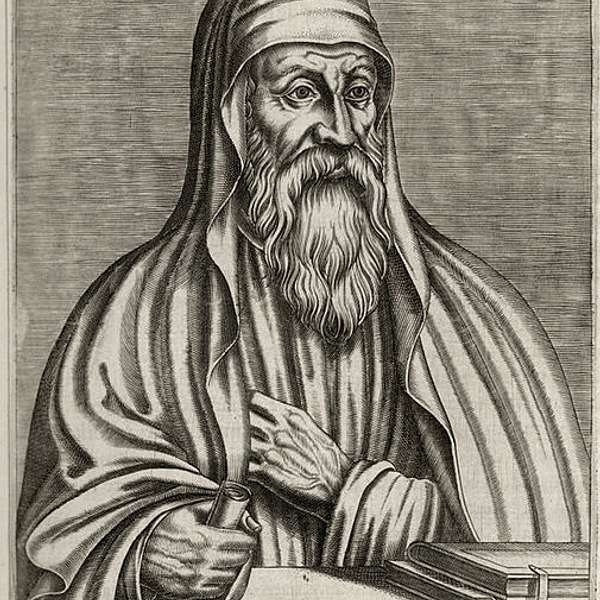

Unit 4: Origen (Season 3)

Unit 5: Athanasius the Great (Season 3)

Unit 6: The Cappadocian Fathers (Season 3)

Unit 7: Augustine of Hippo (Season 3)

Unit 8: John Chrysostom (Season 3)

Unit 9: Cyril of Alexandria (Season 3)

Unit 14: Gregory Palamas (Season 1)

Unit 15: John of the Ladder (Season 4)

Unit 16: Silouan and Sophrony the Athonites (Season 2)

MISCELLANEOUS

Members-only: Special Editions (Season 5)

Empirical Dogmatics: The Theology of Fr. John Romanides (Season 6)

Recommended background reading: Christopher Veniamin, ed., Saint Gregory Palamas: The Homilies ; and The Enlargement of the Heart, by Archimandrite Zacharias ; Christopher Veniamin, ed., Saint Gregory Palamas: The Homilies (Dalton PA: 2022) ; The Orthodox Understanding of Salvation: "Theosis" in Scripture and Tradition (2016) ; The Transfiguration of Christ in Greek Patristic Literature (2022) ; and Metropolitan Hierotheos Vlachos, Empirical Dogmatics of the Orthodox Catholic Church: According to the Spoken Teaching of Father John Romanides, Vol. 1 (2012), Vol. 2 (repr. ed. 2020).

It is hoped that these presentations will help the enquirer discern the profound interrelationship between Orthodox theology and the Orthodox Christian life, and to identify the ascetic and pastoral significance of the Orthodox ethos contained therein.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: I wish to express my indebtedness to the spoken and written traditions of Sts Silouan and Sophrony the Athonites, Fr. Zacharias Zacharou, Fr. Kyrill Akon, Fr. Raphael Noica, Fr. Symeon Brüschweiler; Fr. John Romanides, Fr. Pavlos Englezakis, Fr. Georges Florovsky, Prof. Constantine Scouteris, Prof. George Mantzarides, Prof. John Fountoulis, Mtp Hierotheos Vlachos, Mtp Kallistos Ware, and Prof. Panayiotes Chrestou. My presentations have been enriched by all of the above sources. Responsibility however for the content of my presentations is of course mine alone. ©Christopher Veniamin 2024

Mystical Theology: Introducing the Theology and Spiritual Life of the Orthodox Church

Episode 9: "Origen", Part 3, in "Mystical Theology", with Dr. Christopher Veniamin

Series: Mystical Theology

Episode 9: Origen, Part 3

Introducing the theology and spiritual life of the Orthodox Church, with particular reference to the Holy Bible and the witness of the Church Fathers, past and present.

Origen, who flourished in the 3rd Century, is one of the most difficult and important chapters in the history of early Christian doctrine. An Orthodox appreciation of Origen is crucial for the understanding of the Biblical and Patristic tradition of the Church.

In this Episode, "Origen”, Part 3, which begins with Origen’s understanding of the Transfiguration of Christ, attention is given to the curious intellectualistic character of his theology, the blurring of the fundamental Biblical Patristic distinction, and the preeminence of the philosophical Spirit-Matter distinction in his thought. Reference is also made to the post-Augustinian theological tradition of the West, and comparisons are made with such representatives of the Orthodox tradition as Irenaeus of Lyons, Athanasius the Great, the Cappadocian Fathers (particularly Gregory of Nyssa), Maximus the Confessor, John Damascene, Silouan the Athonite, and Paisios the Athonite.

It is hoped that these presentations will help the enquirer discern the interwoven character of theology and Christian living, and to identify the ascetic and pastoral significance of the Orthodox ethos.

Q&As related to Episode 9 available in The Professor’s Blog.

Recommended background reading: Christopher Veniamin, ed., Saint Gregory Palamas: The Homilies (Dalton PA: 2022).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: I wish to express my indebtedness to the spoken and written traditions of Sts Silouan and Sophrony the Athonites, Fr. Zacharias Zacharou, Fr. Kyrill Akon, Fr. Raphael Noica, Fr. Symeon Brüschweiler; Fr. John Romanides, Fr. Pavlos Englezakis, Fr. Georges F

Join the Mount Thabor Academy Podcasts and help us to bring podcasts on Orthodox theology and the spiritual life to the wider community.

Dr. Christopher Veniamin

Join The Mount Thabor Academy

https://www.buzzsprout.com/2232462/support

THE MOUNT THABOR ACADEMY (YouTube)

THE MOUNT THABOR ACADEMY (Patreon)

Print Books by MOUNT THABOR PUBLISHING

eBooks

Amazon

Google

Apple

Kobo

B&N

Further Info & Bibliography

The Professor's Blog

Further bibliography may be found in our Scholar's Corner

Contact us: info@mountthabor.com...

But, as I mentioned before, it was revealing to me when I had the opportunity to study the question of the place of the transfiguration in origin, because it shed so much light on questions which are still being debated today. For origin, the transfiguration is not a perfect theophany because it's characterized by a vision. It's characterized by a vision of Christ in his incarnate state. It's characterized by a physical reaction on the part of the disciples. They fell to the ground, they reacted to the vision in a physical way. I mentioned also that the appearance of Moses and Elias and the significance of them appearing as spirits is interesting because origin implies that their state is superior to Christ's own state at the event of the transfiguration. And it's interesting, I must mention to you, a friend and disciple of Pamphylus was Eusebius of Caesarea, and Eusebius of Caesarea is an originist. He follows the teachings of origin of Pamphylus and there's an interesting letter that survives, written by Eusebius of Caesarea, in response to Constantia, the sister of St Constantine the Great, who had requested from Eusebius an icon of the transfiguration. She innocently asked him for an icon of the transfiguration and Eusebius responds in this long letter and he says what kind of icon do you expect me to give you? Do you want an icon of Christ in his transfigured state, which is an intermediate glory, when now, after the transfiguration, after the ascension, after Pentecost, christ exists in his full glory? And, by the way, there's no icon for that, according to Eusebius, because it's understood, what would it be? An icon of the intellectualis natura simplex? It would be a spiritual, would be an invisible icon, if that's not an absurdity to say so. In that letter, origins own comments, interpretation of the transfiguration, are confirmed that transfiguration is not considered to be a full and perfect theophany. And it's interesting that Augustine did not regard the transfiguration as perfect theophany. In fact he categorized the different levels of theophany or revelation. He said first you have interlection, then you have the level on which God appears, but not as a physical body. So the appearance of God, high and mighty, to Isaiah, for example, as a spirit that's superior to his appearance. This is Augustine now, not Origins.

Speaker 1:Augustine says when the angel Yahweh Logos appeared to Abraham at the hospitality of Abraham and Sarah, that's a third level theophany, like the transfiguration, because he's appearing in the form of a man. Remember the scriptures say three men, three angels, three men interchangeably. What is the shape of the angels. They appear as men. They may be depicted with wings, but they appear as men and we know that the two angels are created servants of God. They're the ones who go on to Sodom and Gomorrah. The central angel is the Logos.

Speaker 1:Saint Augustine says this is third rate, the burning bush. The problem with the burning bush is that it's also characterized by physicality, a material object. From Saint Augustine we have the tradition that regards these theophany as a bush. It goes up in flames and the amazing thing is that this bush was not consumed.

Speaker 1:So, going back to Origin, you see that the physicality, the corporate reality, his understanding of reality as being pure spirit, in as much as the physical, material world is characterized by change and therefore imperfection. Material things, the body etc. Come into being, pass out of existence and therefore nothing is permanent, nothing is stable. Only the spiritual is pure existence because it is free of this change. That is a fundamental characteristic of the material, of the body, of corporate reality. So, yes, there is something to be said for that, but I'm afraid you can't go down the road of spiritualizing the human body to the point of dematerialization if you want to remain within the realm of Christian teaching, especially, of course I'm referring to the resurrection of the body at the last day, which, after all, is what the Transfiguration reveals to us God's purpose in His creation of man. When we see Christ resplendent in His divine glory, shining in and through the assumed human flesh of Christ, this is significant because he is revealing to us why he created us, what we have been called to become, because in Himself he always had this glory. This glory was His since everlasting. The significance is that God wills to share His very life with His creature.

Speaker 1:But I want to read a passage in concluding Origin to show you how rich and how suggestive, and yet how controversial Origin is. Perhaps the great significance of Origin's contribution is that he raised certain questions more than the answers to which he gave them. I'm going to read a passage from the Contrakelson against Kelsus 2, paragraph 64, translated by Henry Chadwick, which is the quotation that serves to illustrate Origin's view of the many aspects of Christ, which is bound up with his understanding of the relation between divine revelation, that is, the manifestation of the logos for the spiritual life, which for him means the life of the soul. Origin says, although Jesus was one, he had several aspects. To those who saw Him he did not appear alike to all, that he had many aspects, as clear from the saying I am the way, the truth and the life, and I am the bread and I am the door, and countless other such sayings. Moreover, that His appearance was not just the same to those who saw Him, but varied according to their individual capacity, will be clear to people who carefully consider why, when about to be transfigured on the high mountain, he did not take all the apostles, but only Peter, james and John, for they alone had the capacity to see His glory at that time and were able also to perceive Moses and Elijah when they appeared in glory and to hear them conversing together and the voice from heaven out of the cloud.

Speaker 1:I think that at the time before he ascended the mountain, when His disciples alone came to Him and he taught them the beatitudes, even here, when he was somewhere lower down the mountain, when it was late and he healed those brought to Him, delivering them from all illness and disease, he did not appear the same to those who were ill and needed His healing as he did to those who were able to ascend the mountain with Him and were in good health. Furthermore, he privately explained to His disciples the parables which had been spoken to the crowds outside with the meaning concealed. Just as those who heard the explanation of the parables had a greater capacity to hear than those who heard the parables without any explanations, so also was this the case with their vision, certainly with that of their souls and I think also of their bodies. And it is clear that he did not always appear the same from the remark of Judas when about to betray Him, for he said to the crowd that came with Him Whomsoever I kiss, it is he. I think that the Savior Himself also makes this point clear by the words I was daily with you in the temple, teaching, and you laid no hand upon me. Accordingly, as we hold that Jesus was such a wonderful person, not only as to the divinity within Him, which was hidden from the multitude, but also as to His body, which was transfigured when he wished and before Whom he wished, we affirm that everyone had the capacity to see Jesus only when he had not put off the principalities and powers and had not yet died to sin. But after he had put off principalities and powers, all those who formerly saw Him could not look upon Him as he no longer had anything about Him that could be seen by the multitude. For this reason it was out of consideration for them that he did not appear to all after rising from the dead.

Speaker 1:This is a difficult passage and it needs to be read several times before you begin to grasp all the nuances of it. But I think you can begin to see why origin is brilliant on the one hand, but also controversial. So three points of recapitulation on origin. The first we would say that the line of demarcation between uncreated and created is blurred. Origin does have a sense of the three persons, of the Holy Trinity as other, but he diminishes the demarcation between them in two ways. Firstly, the Son and the Holy Spirit appear to be on a lower level than the Father. The word ktizmata creatures is used. Only the Father is Theos, or Theos the God. Secondly, he speaks in a Platonic way of a kinship between the Noose and God. The second point related to the question of the Noose is that he inclines towards a noetic optimism. In other words, the Noose is capable of understanding God. And thirdly, we noted that his theology contains both a circular and a linear view. Ontologically and cosmologically he appears to be circular and on the moral level linear. Now you may think that there we've dispensed with origin.

Speaker 1:But not a few have described with some justification the fourth century theological controversies as a debate over the theology of origin. Florovsky says, for example in his Eastern Fathers of the Fourth Century, page 17, the problems of Arian theology can be understood only in terms of the premises of origin's system. So in both originist theology and Arianism we find a fear of modalism. The struggle against Arianism, says Florovsky, was actually a struggle against originism. But it wasn't as simple as that because, as we've noted already, the Orthodox too, or many of them, and especially Alexander of Alexandria, were originists themselves. It's not difficult to see how the Arians arrived at their conclusions by not merely misinterpreting origin's teachings, but from following his actual premises Historically.

Speaker 1:Again a quotation from Florovsky the defeat of Arianism proved at the same time to be a defeat of originism, at least intranetarian theology quote-unquote. And Florovsky continues to make a number of interesting and very important points. At that time, for example, the system of origin as a whole had not yet been subjected to debate, and the general question of its validity was raised only at the very end of the century. Florovsky also says origin's trinitarian doctrine was silently renounced. And even such a consistent originist as Didymus. Didymus the Blind was free from origin's influence. In his dogma of the trinity, he was even further from origin than Athanasius. Thus, originism was not only rejected but overcome, and this is the positive contribution which the Arian controversy made to theology, says Florovsky again.

Speaker 1:Well, as we already said, nicaea 325 is certainly a watershed in the history of Christianity. It proclaims that the Logos is true God, one in essence or substance with the Father, o Moousios topatri, while for the Arians, the divine Logos, despite their efforts, by the application of various epithets and qualifications, to underline the Logos' uniqueness, was clearly, in the final analysis, to be ranked as a creature because of the way that they understood the term begotten. So where do Aearius and Athanasius actually agree? Let's begin from that point, and I would make two observations in particular. And this is in contrast to origin. Both of them, aearius and Athanasius, believed that creation was out of nothing, creazio ex nihilo. Both the world and everything in it was created. So every aspect of man's being, including his soul and, yes, his noose, was clearly placed on the side of things created. Both Athanasius and Aearius applied the strict line of demarcation between the created and the uncreated, differing only as to where to draw it the orthodox between father and son, and then all creation, while the Aryans placed it firmly between God the Father and all else, including his divine son and Logos. So there you have the first point on which Aearius and Athanasius agreed.

Speaker 1:The second, even more interestingly, I think the Son and Word of God is at the heart, the very centre of every theophany and is thus the one through whom we are saved. They agreed on this. He is the one through whom we are glorified or deified. So he's the instrument, the organon, the one through which we are glorified, we are deified, but is the glory by which he glorifies us, his by nature or merely by grace? If we take the latter view, then the divine Logos can be no more than an exalted creature, albeit the most exalted. If we hold to the former, then it must also follow that he is of one and the same substance, essence or nature with God the Father, in which case the homoousion would be meat and proper in defining the Son's relation to God the Father. So those are the two points, the two major points on which the Aryans and the Orthodox agreed, the Cappadocians, of course, who take up the work of Athanasius, the Orthodox cause against the later Aryans, against Eunomius and company, emphasise also the homoousion of the Holy Spirit. So origin the Aryans and later the Macedonians, and visage a descending hierarchy of being, while for Athanasius and the Cappadocians there is no natural kinship between man and God. God, in other words, is totally and absolutely other as uncreated and everything else, including the human race and the angelic powers, are created.

Speaker 1:A difficult and challenging chapter always is origin. It would appear that there is some truth in the theory that origin started one way and then developed in another later on. I think there might be some truth to that because there's no question about the piety, the ascetic character of origin's life, his deep love for Jesus Christ, the Holy Scriptures, the Church and so on and so forth, and it seems to me that what happened to origin is that he begins his life and his studies as a very deeply pious man and never, even later on, had any intention of introducing some doctrine. That might be considered questionable, but what I think happened is that as he grew up and realised that if he was going to engage in dialogue with the world around him, he would have to have certain tools in order to be able to do that effectively. So he began to learn Hebrew and he began to study the different philosophies, the different religious traditions around him. Remember, we said that Alexandria was probably the first multicultural city in the history of mankind, and so it was a very interesting place to be with all kinds of creeds and religions and philosophies around. And so as he familiarized himself with these things, something began to rub off on him, and so it's interesting how that happens. And if you look at church history, we'll teach you that where people were most in dialogue with opponents, you see them influenced by that dialogue. So you're in dialogue, you're disagreeing with your theological opponent, and you actually are not uninfluenced, in the end, by that dialogue. So, growing up in this culture and becoming more of an intellectual, developing as an intellectual, he began to, in his reasoning, thinking things through, be influenced by certain elements.

Speaker 1:At what stage did this begin? Was it after St Gregory the Wonderworker knew origin and was taught by him, or was it before? I think that origin's involvement and learning about the world around him began very early in his life, when he was in his teens. So I think there have always been efforts to re-evaluate certain figures who might have been treated harshly or wrongly, unfairly this is a common thing. But in the case of origin he actually fits in very well with the post-Augustinian Western theological tradition because so many of his fundamental presuppositions are shared. They may not be deliberately trying to follow origin, but they share the presuppositions of origin, at least of many of them, and in some cases, as I said also, I think origin is a more sophisticated version of what you find in the West. Also, we have to say, and I think that was also said, perhaps implicitly more than explicitly but in the East you had people who followed after origin, who could correct origin, whereas that doesn't seem to be the case in the West.

Speaker 1:The immediate disciples, the near contemporaries of Augustin in the West didn't seem to have the same or a similar stature and the ability to correct Augustin. But if you look at the Latin-speaking tradition of the West, you'll see that Hilary of Partier, ambrose of Milan, gregory the Great there are a number of important figures there, fathers of the Church, who are in absolute agreement with the East, but in close proximity to Augustin. He was isolated, was a big fish in a small pond in North Africa and he preferred to stay there, and later on. It was only after the so-called Dark Ages that they decided to make him the man in the East. However, where do you find people following Augustin? Perhaps they didn't know Augustin very well, but nobody really follows Augustin in the Orthodox tradition. So origin is difficult, augustin is difficult.

Speaker 1:Origin is someone who shares a number of fundamental presuppositions with Augustin. Perhaps we should say it the other way around, since, chronologically, origin comes first. Regarding the common presuppositions, we're talking about the blurring of the most fundamental distinction of all and that is the created-uncreated distinction. And what happens with origin, and it also happens with Augustin, is that the spirit-matter distinction is more prominent than the created-uncreated distinction. The created-uncreated distinction is blurred and the spirit-matter distinction is the one that becomes preeminent. And what that means is because there is a spirit-matter distinction. It's just that it's not a philosophical one and it's in the context. In the Orthodox tradition it is to be found within the context of the created-uncreated distinction. When we take a look at, say, maximus the Confessor, for example, and we look at his five dualities, the five levels on which man is called to become a mediator and to unify the cosmos in his person, see the first level. The highest level is that of created-uncreated and then spirit-matter. So it's there, it's Orthodox, there's nothing wrong with it when it's in its proper context.

Speaker 1:What happens with Origen and Augustine? We said that in Origen we have a philosophical understanding of the Nus. That also applies to Augustine. You have a conceptual understanding of the spirit-matter distinction, in other words a philosophical one. There's a lot that we could say about that and we are in the process of unpacking that. We are in fact addressing it already. But as we go along we'll look at it again from different angles, in different persons, in different contexts, doctrines and so on and so forth.

Speaker 1:But that's what I would say for starters. I mean that's the big and most fundamental distinction, the created-uncreated distinction, because it's from there that you derive what we spoke about. In other words, the world and all its glory, including man, cannot teach you who God is, the fact that we've created in the image of God. Still, you cannot discover who God is by means of the world, by means of the creature, the creation. The only way to receive knowledge of God is directly from God, in and through Jesus Christ. We saw that already in Saint Irenaeus of Lyon. The sole revealer of God is Jesus Christ.

Speaker 1:So the argument that. Well, the world is created by God, and so if you study the world and learn about the world, it will lead you to that God and to who he is. That belongs to another tradition. That belongs to that post-Augustinian tradition of the West. It's not the tradition of the Bible or of the Fathers in the Orthodox tradition. That we are in the image of God, as we've said, means that we have the capacity, when transformed by the grace of God, to contain his life. Not that there's some aspect of us which is akin to God by nature. But we're going to look at Saint Augustine, god willing, and more of his fundamental theological presuppositions, comparing him with the Cappadocians on the Trinitarian question of first, and then going more generally to look at how the context of his theology presents us with a fundamentally different world.