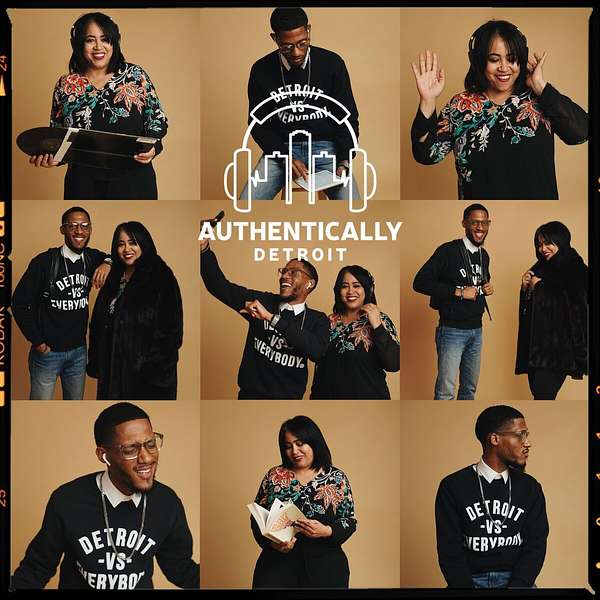

Authentically Detroit

Authentically Detroit is the leading podcast in the city for candid conversations, exchanging progressive ideas, and centering resident perspectives on current events.

Hosted by Donna Givens Davidson and Orlando P. Bailey.

Produced by Sarah Johnson and Engineered by Griffin Hutchings.

Check us out on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter @AuthenticallyDetroit!

Authentically Detroit

Book Club: We Want Our Bodies Back with jessica Care moore

This week, Donna and Orlando held the final book club meeting of 2024 with celebrated poet, author, and cultural arts curator, jessica Care moore to discuss her impactful work, “We Want Our Bodies Back.”

An award-winning poet, recording artist, book publisher, activist, cultural arts curator, and filmmaker, jessica is executive producer and founder of Black WOMEN Rock! - Daughters of Betty, a 20-year-old rock & roll institution, concert and empowerment weekend, and she is the founder of the literacy driven 501c3, The Moore Art House. Her nonprofit organization in Detroit dedicated to elevating literacy through the arts in neighborhoods and schools.

Jessica's publishing house, Moore Black Press, has published poets including Saul Williams, Newark Mayor Ras Baraka, asha bandele, and Danny Simmons, and in 2024 is preparing to publish their first poetry and spoken word audiobooks through an imprint deal with HarperCollins.

To learn more about jessica Care moore, click here!

Up next. Authentically, detroit welcomes Jessica Caremore, the author of we Want Our Bodies Back for a live book club discussion at the Stoudemire. Keep it locked. Authentically Detroit starts after these messages.

Speaker 2:Founded in 2021, the Stoudemire is a membership-based community recreation and wellness center centrally located on the east side of Detroit. Membership in the Stoudemire is available on a sliding scale for up to $20 per year or 20 hours of volunteer time. The Stoudemire is available on a sliding scale for up to $20 per year or 20 hours of volunteer time. The Stoudemire offers art, dance and fitness classes, community meetings and events, resource fairs, pop-up events, the Neighborhood Tech Hub and more. Members who are residents of the Eastside have access to exclusive services in the Wellness Network. Join today and live well, play well, be well. Visit ecndetroitorg.

Speaker 1:Hey y'all, it's Orlando. Visit ecndetroitorg. Hello Detroit in the world. Welcome to another episode of Authentically Detroit broadcasting live from Detroit's Eastside at the Stoudemire inside of the Eastside Community Network headquarters. I'm Orlando Bailey.

Speaker 3:And I'm Donna Givens-Davidson.

Speaker 1:Thank you for listening in and supporting our efforts to build a platform of authentic voices for real people in the city of Detroit. We want you to like, rate and subscribe to our podcast on all platforms. Happy holidays, everyone. We're here for another live recording of the Authentically Detroit Book Club at the Stoudemire. For the first time, we are featuring a book written by poet, book publisher, cultural arts curator, institution builder, recording artist and the voice of Detroit, jessica Care Moore. Here's the quote Jessica Care Moore is one of the leading voices of her generation, an award-winning poet, recording artist, book publisher, activist, cultural arts curator and filmmaker. She is the executive producer and founder of Black Women Rock Daughters of Betty, a 20-year-old rock and roll institution concert and empowerment weekend, and she is the founder of the literacy-driven 501c3, the Moore Art House, her nonprofit organization in Detroit dedicated to elevating literacy through the arts in neighborhoods and schools. Moore's publishing house, moore Black Press, has published poets including Saul Williams, newark Mayor Ras Bar, prisons, universities, art institutions and global community causes around the world. In 2020, with the release of we Want Our Bodies Back, she became the first black woman poet to publish a book with HarperCollins since Gwendolyn Brooks At the mantle, a culture and news site based in New York, a reviewer said to say that this book is revolutionary is an understatement.

Speaker 1:It's an ode to womanhood and an ode to blackness. We know that trauma is held in the body and through the book's title, moore urges us to take ours back, to love them, to forgive them and to honor them. She writes a constellation of poems. Live inside their wombs, waiting to be born again. A rebirth is always possible. She reckons with what it means to be a black girl that doesn't fit into a predetermined box. Moore provides a blueprint for how to veer outside of fixed expectations and still remain unflinching in her love for herself. She writes with familiarity, like she's inviting you into to sit at her kitchen table as she tells stories about your own beauty and hope that you'll believe her. And even if you don't, it doesn't stop it from being true. Sometimes we need to be reminded of our potential and for the first time ever, I am happy to say these words Jessica Caremore, welcome to Authentically.

Speaker 4:Detroit. Oh my God, it's a beautiful intro I'm like dun-dun-dun-dun. Thank you. Anytime you ask me to do anything, I show up.

Speaker 1:Oh, thank you. Thank you, how are you doing?

Speaker 4:It's been a day, it's been a long weekend. My son, king, was visiting from CalArts. My son is a freshman.

Speaker 1:I still can't believe you ain't bought a house in California to be close to King yet Well, yeah Well, buying a house in California requires a lot of things I'm thinking about being bi-coastal. Yeah.

Speaker 4:Yeah, but not to be close to King just because I want to do more work in the film world.

Speaker 1:Yeah.

Speaker 4:But I want to shoot my movies in Detroit. Yeah, just want to maybe make some deals there.

Speaker 1:Yeah.

Speaker 4:Go get some coins from LA.

Speaker 2:Yeah.

Speaker 1:And some sunshine, and some sunshine.

Speaker 4:Yeah, there's, I think, a balance of Detroit a Detroit West Coast there.

Speaker 4:I know so I'm not running out and I got things to do here. I just did an amazing event. Poet laureate of the city of Detroit. I'm going to stick around. How does it feel to be you right now? Tired man? I'm a little tired, but I just did this amazing, my first to me, my first kind of official. People have asked me to do things and I've shown up. But the first thing that I produced as a poet laureate was my Poet T with Girls 12 and Under this Saturday at Rosa Detroit on Grand River on the west side. It was Rashida Tlaib showed up, which was really amazing. Thank you, rashida, for showing up.

Speaker 1:She's a friend to the show. She's amazing.

Speaker 4:She walked in. I was like I've done something great. But I thought about 60 girls signed up but because of the weather we got about 30, 35.

Speaker 3:That's still a great number.

Speaker 4:But because of the weather we got about 30, 35. That's still a great number. Oh, it was amazing. It was like a classroom, you know, with all different little girls from all different walks of life, from different spaces, Moms and dads that I knew some were strangers that just signed up on Eventbrite, but we did a tea and so they had a black tea company, Herbal Serenity. This sister showed up and did a free kind of tea tasting, so they had to taste a herbal tea. I had an iced chai tea for them and we had hot chocolate and I gave them all cups and porcelain cups and saucers and, like anything you could think of, Bubbles with tea kettles on top. And I'm a tea drinker. My mother, who people may not know, is from Wolverhampton, England, and so I grew up drinking tea my whole life. So tea, culturally, has been a part of my life and I love it. My album with Talib that came out in 2015 is called Black Tea which is a nod to my mother and father.

Speaker 1:What was the impetus behind you? Wanting to create this space, especially for young women, young ladies?

Speaker 4:Yeah, you know my son King. My son King created the 12 and under super cool poetry open mic when he was nine years old. He's the youngest night arts winner in the history of night arts. He won a $15,000 matching grant and it was his idea to, because he was reading poems in front of grownups and grownups were like oh, clapping for my son and he was like mommy, this is cool. Grownups and grownups were like oh, clapping for my son and he was like mommy, this is cool, but I want to do my poems around people my age and I was like, well, create the space. Then you be a boy, fella, do it. And he created the idea and we applied for the grant together and he won. He won before I did.

Speaker 1:Anyway, he won. Well, at least he won. I never got it, you know.

Speaker 3:I never got it. I was there when he won.

Speaker 4:You were there when he got his pickup.

Speaker 3:I was there when he won and it was like oh my goodness.

Speaker 3:I was so impressed with the relationship that you had with your son, and one of the great things about we Want Our Bodies Back is you don't just speak of yourself, you speak of yourself as a mother and you speak of children, and so I really reading it. I identify with so many parts. Like I told you, I had to re-read so many poems so far. I think I've read many of them twice or three times, but there's three things I identify with so much. One of them is the scar on your face.

Speaker 4:I've been writing about that a long time.

Speaker 3:I've been writing about my scar a long time, so I've got scars on both my eyes same kind of thing and so in one there was so much blood in my eye I thought I was blind, and so when you talked about that, I identified with that there may be two edges in being blind.

Speaker 4:Yes, exactly.

Speaker 3:I was like, oh my goodness, that was me. And then the second one that you talked about was being a sort of slow to develop girl, and that was me too. I was like in ninth grade like.

Speaker 2:am I ever going to get that glimpse?

Speaker 3:Yes, and yes, and then the other one that I was allowed to be a girl. Right. And then the other one was your love of speed and the fact that you were running beating the boys and stuff like that.

Speaker 4:That was me Trying to keep up with my brothers.

Speaker 3:And I thought you know there's so many different parts of yourself and I thought how many women can read this and see pieces of themselves Not the pieces I have, but I think that you created narratives where other people could see themselves through your eyes, or maybe you were narrating our story in ways that we hadn't thought about. Can you talk about your impetus for that and how you, what, your what did I say? Oh, my no, I mean I'm kidding. I mean so many, so many poems yeah.

Speaker 4:I mean, I'm just telling my story, you know, and I think when you tell your story in an authentic way, authentically Detroit, when you're authentically telling your story and not really I'm not thinking about any of those things that you're saying, when I'm writing, I'm just telling my stories, and because I'm just telling the truth, when you tell the truth, people can relate to honesty, and I think that's what you hear, and I think I hear that with a lot of women writers that I love, like Nikki Feeney and Asha Bandeli, who we mentioned earlier, who I was able to publish many years ago, audre Lorde and Sonia Sanchez and Nikki Giovanni, and these writers that have pulled me up and taken care of me since I was a little girl. Those writers, those women, are so honest. Women writers just tell the hardest things very openly and because of that, that's why you can relate to it.

Speaker 3:There was this one line I don't remember the exact words where you say a man might repeat our words and call it vision, or something like that.

Speaker 1:No, a man may see the world from a woman's point of view and call it vision.

Speaker 3:I was like, yes, one day yeah. One day, one day, yeah, well but sometimes I thought sometimes that does happen right. But sometimes I thought sometimes that does happen right. And sometimes they call it vision and sometimes they own our words and our view as their vision when it really came from us. So many times we have our thoughts and our you know stuff gentrified or taken from us.

Speaker 4:Oh yeah, I've been stolen from. You know, I'm glad I have a big imagination, so when people steal my things I can just come up with some new things you know. And then women you know. Any great man like what y'all know, I do black woman rock for 20 years Right Supporting black women in rock and roll. But like I always say, you know, if not for Betty Davis, there will be no interesting Miles Davis.

Speaker 4:And you invoked Betty a lot in the book oh yeah, Betty is there Talk about what she, what she told you. She told me so many things and she has a really great quote about because we always say Betty Davis was before her time.

Speaker 4:So like women like me. I've been told, jessica, you're before your time and she said, no, I wasn't before my time, I was moving time, and that's Betty has been very important to me. She passed away, as some of you may know, a few years ago. We lost her, but for years we corresponded. She sent me letters and photographs and thanked me for keeping her music the last letter she sent.

Speaker 1:What did it say?

Speaker 4:um, she's the last thing she's, thank you.

Speaker 1:Thank you for keeping my music yeah, that was the last that part. Yeah, that moved me. When I read it I was just like, oh my gosh yeah, that's crazy.

Speaker 4:When I got that, I was like I'm done, you know. Like you know, people do things because they want awards or recognition and I was like I just want Bette Davis to hear us and even with this book, we want our bodies back. The title piece is for Sandra Bland and the title poem is a heavy poem.

Speaker 2:It's very heavy.

Speaker 4:Thank you, and I've read it in spaces where people were like, oh my, and I do it. It's not an easy poem to read. You an easy poem to read, you know, because I'd be gone. I was gone when I was reading it and when I was writing it I'd be gone.

Speaker 1:You know when the writing would go away and black women made the world notice what happened to Sandra Bland.

Speaker 3:And you know.

Speaker 1:Jessica, I think the last time I interviewed you I was interviewing you at Robert Courtney's thing, CreatorCon and I talked about how lauded you are, but you also said that you still have to fight for space. Of course I do. Yeah, talk about that.

Speaker 4:Well, I don't know. It's an interesting space Detroit, hi Detroit, a high place where I have to fight for space. Still, despite being Poet Laureate, despite 20 years of doing Black on the Rock and bringing that home. After creating it in Atlanta, georgia, with the National Black Arts Festival in 2004, I funded self-funded my event at the Fillmore. I spent I lost thousands of dollars on that show. I paid all the women out of pocket. The only organization that supported me for my 20th anniversary was Rochelle Riley in the city of Detroit, yeah, arts and.

Speaker 4:Culture found some funding, but not enough to maybe get the women here, but not for anything else. And so and I paid for ads and I did all I could do, but it's unfortunate when you're doing this work, see, I found like during 2020, black women's voices and black people's voices were very avant-garde when George Floyd died and everyone was looking at racism in an upfront way and having to confront it.

Speaker 1:corporations showed up. Yeah, we were home, we had to see it.

Speaker 4:Well, now it's like they don't have to Now with the new, the regime that's about to be in place. That's getting rid of DEI and getting rid of basically trying to get rid of us, because you know you too much. Those are acronyms, but truly it's like a way to get rid of black and brown voices, um, in an institutional kind of way that we really need those spaces so that person like me can have those people who want to get grants to fund artists like me to exist.

Speaker 1:That's how sometimes their funding comes that way you write yourself and the experience of so many black women and little black boys.

Speaker 4:Oh yeah.

Speaker 1:Into the world. Yeah, and we want our bodies back in such a revolutionary way. Go ahead, donna.

Speaker 3:Well, I am not ready to die.

Speaker 4:I love. We want our bodies back and I love.

Speaker 3:I'm not ready to die this line. My headphones sound like Sade. I wish these girls would get the fuck off their knees and transform a room.

Speaker 4:You can cut. Okay, we just need to put a warning up.

Speaker 3:But yes, we can, okay, we don't do it often, Of course.

Speaker 4:I get the warning on my show. No, Yusuf Shakur has been here. Yusuf Shakur also gets the warning.

Speaker 3:Sometimes I slip, but you know, and transform a Room with Subtle Power and Grace. Talk about that and the motivation or inspiration from that, because I love that, that line, yeah, yes, this one I'm not ready to die the poem.

Speaker 4:If y'all haven't read it yet, y'all better go get this book. I'm looking at people looking at me that didn't read the book while we're talking about the book. But anyway, I'm not ready to die. Someone called me on the floor at one of these random award shows and I was just like who? And it doesn't matter who it was, because so many have crawled on the ground, which I mean I'm into, like sex is great and you can be sexy without selling yourself out for it. And so I wrote this poem for young girls and women to know that I'm not ready to die this way and if I die, I'm not going to die crawling on my knees with somebody else's entertainment. And so this line you know, I wish these new girls my headphones sound like Sade, because if you know who Sade is with her new record she got my friend Ryan plays guitar for her and she's got a new record out. But anyway, sade is exquisite.

Speaker 1:She is exquisite.

Speaker 4:I've seen her in concert four or five times when Indie Irie was touring with her and Sade barely move on stage. Sade ain't got to do much but open her mouth and she just got one little move and she's just super fine. And she might go to the right and she might go to the left, but she's just super fine. And she got one little. And she might go to the right and she might go to the left, but she's not doing a whole bunch of acrobatics but she's explosive and her music's so good. And so that's what I mean, like the subtle and power of grace of Sade. We would just take some notes. Even years ago I remember Annie Lennox said, who I had the pleasure of meeting briefly at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame a few years ago, and she said I wish the new girls wouldn't give it up so quick. I wish they would. Just I get it, I get you want to be famous, but don't give them everything so fast.

Speaker 3:Well, you know, sometimes I get so irritated I know it's my age, right, but sometimes I'm watching TV and every time you got to turn around and do a twerk and show your butt and everybody does that at what point does this cease to be special and at what point does this look like you are exploiting yourself and I know that it's like well, I own my own body and you're not going to objectify me, but does objectifying myself, is that better than being objectified? At what point do we own our bodies in such a way that we take pride in who we are and we don't do those things?

Speaker 4:You know, I always feel like I'm not anti-twerk, I'm not anti any dance moves, I'm not anti, it's like my whole thing is who are you doing it? For? If I'm on stage at Black on the Rock and I have on almost nothing, which it does go down I'd be naked and fine and making brothers have to just blink. You know I believe in that shit and so, but no one told me what to wear.

Speaker 4:No one's telling me and trust me, no one at those award shows, those young artists. They're being told this is your outfit, this is the choreography.

Speaker 3:You know what I mean. That's what I'm trying to say. I agree with that. Own it, but it's like it's not even interesting. Sometimes. It's like everybody's doing the exact same move. It is this. It's the industry really saying this is what women are, this is what black women are. Black women, if you're going to come out here, this is what we want you to do, be who you are. I'm not anti, anything.

Speaker 4:I'm anti boring media, anti mediocrity Exactly, and it just feels like there's, you have more of it.

Speaker 3:Like I listened to some people's music and you get deep in the music and you get deep. But a lot of the stuff that's played on the radio is not the deep stuff. It is the stuff that sells that record executives decide this is what you're going to listen to and this is what's going to represent black womanhood, and so I'm not ready to die. Really said, we're bigger than those things.

Speaker 4:Yeah, and I'm not going to die doing it. And then that thing you're saying has been like the norm. This is the norm, this conversation we've been having since forever. That hip hop is more Like Talia Kweli shout out to Kweli.

Speaker 1:Remember those summits on BET back in the day? We've been having this conversation for a long time. Nothing has changed 106 and Park.

Speaker 4:did it Teen?

Speaker 2:Summit. You know what I mean.

Speaker 4:But there should be some needles being moved right, and because we have satellite radio, thank God, we're not just having to listen to local radio. We have some other options. We have podcasts now that play different radio, different music, and so that's the plus. But the industry is going industry and the industry is not ours. We don't own it.

Speaker 1:Jessica, can I ask you about just how you structured the book so you're telling?

Speaker 4:stories. I'm writing a whole other book right now, so you know this book came out in 2020. I know, I'm so somewhere.

Speaker 1:I know, I know you may be somewhere else, but let me help you jog your memory a little bit. It also feels a little bit autobiographical, right, I get. I get a glimpse into, uh, your childhood and how rambunctious you were. I get a glimpse into your relationship with your father, um and uh, what happened when he got sick and when he was dying, and that strained relationship with his wife at the time, my mommy, yeah, she never, never stopped being his wife.

Speaker 4:Well, who he was with at the time? Not the wife.

Speaker 1:What did I say? You were talking about you know going. What did I say?

Speaker 4:You said some juicy stuff. What did I say? I'll be here by my daddy.

Speaker 1:I didn't mark it, I gotta go back and it must be in my intro. Oh, I gotta find it. But what you were saying was you were talking about your father's body oh yeah, you know like, yeah, post-death, talk a little bit about that. I'm gonna find why.

Speaker 4:While I find it yeah, I mean, I know I talk about my dad, I don't think in the intro, but so my daddy died. It's interesting because you're talking about was this memoir. All my poetry books are the truth. They're all experiences. So I'm not sure what about my. This is my fifth book, not my first. So God is Not an American was my is my third book and probably my favorite book before this one came out. And so if you read God is Not an American, you know who I'm married to, who I'm in love with or who I'm divorcing, or what baby I love or what baby I'm about to have. It's all my business. I wrote God is Not an American when I left my first husband. King was just a baby. Bye, Leave me alone, I can't talk to you. Bye.

Speaker 4:Let me turn this off, Turn off my ringer. So if you read my books like the words don't fit in my mouth. I wrote those poems when I was between 19 and 21. You know, I was very young. Then you hear me in Brooklyn and I'm in New York for the first time. So those poems are like Black Statue of Liberty, Black Girl Juice. Everything in the words don't fit in my mouth is black, black, black. And then I, you know, you grow, and then I think the next book after that was the Alphabet Versus the Ghetto, if I'm not mistaken. But I published so many people in between my books. So I published Sharif Simmons and Saul Williams and Raz Baraka and Asha Bandeli and Etan Thomas and I started publishing people. So my books took a backseat to me publishing other people's work, which is what happens when you're taking care of other people.

Speaker 4:Yeah, so I tried, when God is not an American, to get back to myself, and so God is not an American. Happened, and sunlight through bullet holes happened after that, and now we have. We want our bodies back and so, um, but yes, I talked my daddy.

Speaker 1:You ready I'll read it to you, Okay, okay, see my daddy's body. I wanted to see what they had done to him. Not the angels, not God. They didn't take him. I was convinced he was thin and tall and Southern, sophisticated, cool, mild and Southern comfort. Next to his bed, smile that could capture the attention of women half his age. I laid down in his twin bed the morning he died. I wanted to find the grooves of his body inside the fabric so that I can bury myself inside what he left behind. A part of my body would always be dead.

Speaker 1:After this day, I examined the house that was never my house. I searched for clues. I wrote my eyes at the strange man who was walking around. I didn't trust him, or his smell or his eyes. I didn't trust the woman who was my daddy's young girlfriend at the time of his death. I didn't trust many women. After my daddy's body left Detroit I wanted to see him. Why can't we see him? Henry Ford Hospital had his body somewhere. I forever hate hospitals. The doctor told my brother, johnny, it would be better to just wait until he was prepared for the funeral. We left my daddy's body with these strangers. My brother didn't notice but I was screaming. No one noticed. But I was flying. I was kicking the doctor in the gut and running down the white doorways to find my daddy's body so I can bring him back home with me.

Speaker 4:Oh, yes, I know that that's January 3rd 1994. That's the day my daddy died. So everything after that changed. You know, my life changed. He was my hero. He was my best friend. I used to ride to Alabama in his Cadillacs every summer I went to the truck stop with him.

Speaker 1:He's from Alabama, right.

Speaker 4:He's from Alabama. We are from Alabama a little bit.

Speaker 2:Yeah.

Speaker 4:Alabama, georgia, mississippi, detroit. But yeah, huntsville Madison, he's from Alabama, right, he's from Alabama, we are from Alabama a little bit. Yeah, alabama, georgia, mississippi, detroit.

Speaker 2:But yeah, huntsville.

Speaker 4:Madison. He's buried in Madison. So my first plane ride with my father and I don't know if I've written about it here, but I've written about it in other books is when I'm having to take his casket back home. So I'd never been on a plane. The Cadillac was the plane. He wasn't flying on our planes when we were old and he was much older than my mother 20 years older than my mother.

Speaker 4:So you know that'd be really controversial now. But you know she left him but they were married legally until his death and she never married anybody else and so they have four kids that came out. I hate my crazy siblings, but my daddy actually. I found another brother, jamie. Who you found another brother, jamie, and so there's actually. Oh, you found another brother.

Speaker 2:A brother found me. Really he came to kwanzaa last year. Where was this recently he came? Oh goodness, are we breaking news?

Speaker 4:yeah, no, he came to black on the rock last year. Yeah, he found us. He's in canada. He's older than my brother, mark, so my goodness yeah, so he was older, he hadn't met my mom yet, and so which was good, it wasn't like an in-between.

Speaker 2:It was like my mom was like how old is he? I was like he's older than Mark. He's older, relax, don't worry.

Speaker 4:But we have my brother Billy's, also older, and so I have brothers that could be my daddies, the age-wise as old as my mother, and so my mother kind of came up with my brother Billy. So six brothers all together and two sisters. But the last four of us were who grew up in the house together. But my daddy was everything to me. But after he died in 94, I was at Wayne State at the time I took over Wayne State University with the Black Student Union to help create the King Holiday. They weren't celebrating the King Holiday, they weren't closing classes at Wayne State University in 1994. Shame on them.

Speaker 4:And so my daddy died and I needed something else to do, and so I became very active as an activist. I was already an activist anyway, but I was grieving and didn't know how to grieve, and so I just poured myself into the student body at Wayne State to make some change. And I did that, and then I left. I opened for the last poets here in 1990, was that 1995? And I'm not sure exactly like I'm trying to find my why again. So when my daddy died, my why was gone. I was close to my mom, but not as close as I was to my father, and so I was like I'm going to Brooklyn and nobody could stop me. I would have never gone to New York if my daddy was alive. And so for me he was that push, Say okay, now there's nothing stopping. Stop and you not go. And now I'm at a different crossroads.

Speaker 3:Why are you in the crossroads right now?

Speaker 4:Because my son's not here, because King is in Cal Arts and every time he leaves it's hard, like every time my wheels come back to Detroit after going to visit him. And I've seen him often because I have the privilege of travel, and so it's not like I'm not seeing him, but I'm not being here. I don't know why I'm here, because the only reason why I was here was to raise my child here so he could be with my family. So I'm here because of my family. My mother is like the reason she's still with me. But other than that, I'm trying to figure it out Because when you're not making a living in the city or you're a Detroit Poet Laureate, I don't make I travel for a living.

Speaker 3:So Detroit is not paying you or honoring your work in the way that it should.

Speaker 4:No, that's not what I'm saying, because no artist makes a living in one city. So I've made a living traveling for my whole life, but I don't. Yeah, you know what I mean.

Speaker 3:Let me just say this Well, the 20th anniversary of Black Girls Rock of the Film World, black women, black women.

Speaker 4:I'm sorry, and I don't make a living doing that either, because that's a labor of love and I give all the money to the artists and the musicians and everything. So that's not my, that's not really income for me.

Speaker 1:Well, you know, you often talk about and you actually did a session on this with Urban Consulate. We worked together about two years ago at Urban Consulate in the Cochran House.

Speaker 4:You did a master class on living as an artist. Yeah.

Speaker 1:Right, and even in the book you talk about having to go to DHS, which was real. Those words are seared onto my mind. It's real.

Speaker 2:You have your child.

Speaker 1:You're Jessica Caremore. At this time, you have to go to DHS because you need to feed your child. And they're like do you have to go to dhs because you need to feed your child? And they're like do you have a job? And I'm like, yeah, I'm a poet they're like what's not a job?

Speaker 4:yeah, yeah, and then and I was articulate and I wasn't uh ugly and I had my little baseball cap trying to like you know yeah ugly it up a little bit and the case work is still mad because I'm cuter than her and you know it is what it is, that's like that. That was a course moment in my life and I'll never do it again. And so there's two things. So yeah, no, I would never say Detroit has definitely honored me. I get honored in a lot of places. I don't mean it like that.

Speaker 3:What I mean is a lot of people say that they don't feel like they're honored in their home and they have to go outside. I don't.

Speaker 4:And so yeah, I get paid less here than I get paid. I do make money in Detroit. I've made some money doing corporate storytelling. So Pure Michigan is a corporate contract that I have Absolutely. I got paid to do that, working with Steven. I wrote and moved here. I moved to Detroit for Amazon, steven, who McGee, I love you, steven, sorry.

Speaker 4:Steven McGee. I know I'm saying Steven Steven McGee. I know I'm saying Steven Steven McGee. Him and I have made about 12 short films together. So I work in the corporate world, but as far as just being a poet and a writer, let me say this when I show up to spaces in San Francisco and in New York and other places, my checks are probably quadruple the check that I get here. So people here don't pay me what I deserve and the organizations don't. I don't get booked here. To be honest, very often I've been to some of the universities, but you know Like I should be a poet in residence. I've been a poet in residence at Grinnell College, but never at Michigan State, u of M or Wayne State.

Speaker 3:University. That's what I'm trying to say. Sometimes we take our hometown talent for granted and you have to leave home in order to have people recognize you. It's almost like that. But I want to talk about another poem. Let's get back to the poetry a little bit. Black Ice Bodies oh, wow. I love that.

Speaker 3:I never read that and I never read that poem because it's so long, but I love it it is long, but it's really you honoring Debbie Thomas and Alicia Hall Moran, and also to get recognized as great for doing some of the same things. I think we've seen that in so many ways At least that's what I kind of saw in here.

Speaker 4:We have to put this in context. For the people who were not born in the 70s, they don't know who the heck Debbie Thomas is. Y'all know who Debbie Thomas is One person. Okay, looking at me, don't play me.

Speaker 4:Okay, I'm not going to play you, but Debbie Thomas, world-famous figure skater, olympian, right, but the commentators had a lot to say about how she skated. And there was a woman named Katerina Witt, very famous German skater, who they competed against each other, often right. There's Alicia Hall Moran, who is a very famous opera singer she's my friend and she starred in Poor, gay and Best and there was a thing called the Battle of the Carmens, and that Alicia Hall Moran is an ice skater and opera singer who made a show that I wrote a piece about, debbie Thomas, so it's based on the Katerina Witt and Debbie Thomas rivalry. But if you listen to the commentators, if y'all just go on YouTube and Google this, it will blow your mind the way that the commentators talked about Debbie Thomas, from the way she looked, from her hair, from everything was wrong with her.

Speaker 4:How beautiful Katerina Witt was, though, how perfect she was, how perfect she was, and I feel like Debbie Thomas had to do a quadruple to get to her double, and so, yeah, it's a metaphor for all the extra things that black women, athletes and artists and women and people in corporate arenas, how we have to show up and we can compare it to. We can talk about Kamala Harris and how her resume is better than anybody almost that's ever run for a US President office, and how she was just. I mean the ugly way that I saw her being sexual than anybody almost that's ever run for a US president office, and how she was just. I mean the ugly way that I saw her being sexualized, how they made it seem like she basically had slept her way into every position she ever been.

Speaker 3:It was disgusting. I took it so personally. Every time I heard things like she's the least qualified person to ever run for president. It hurt me personally, not even because of her, but because of me as a woman always having to prove myself and prove myself and prove myself and still not be quite good enough. And then I saw this in your poem and I thought this is a perfect metaphor for the time that we're in as black women, because so many of us are feeling that.

Speaker 4:You're going to read it next time. Yeah, I'm here, let me see.

Speaker 1:I said, katerina, this is like oh my god, she's gonna read this excerpt.

Speaker 4:Yes, I'm going to. What are you talking about? I'm skating to Carmen. It's an opera, it's not. Oh. So the thing is, carmen is an opera, right, so it became this big thing because Debbie and Katerina picked the same music to skate to. So it was the drama of all dramas. Right, this is them. Okay, I'm skating to karma. It's an opera. It's not like we're wearing the same prom dress.

Speaker 4:Katerina, beautiful, gorgeous, a natural beauty. She was crown queen before the bow. They said I had a street smart musicality. Is Katerina not from the streets of East Germany? Does she not have a street smart musicality? These are not shell-toe Adidas. This is not black top. This is black ice. I not shell toe adidas. This is not black top, this is black ice. I didn't take carmen to the east german corner. This was not a break dance beat down in a brooklyn alley. This is figure skating. Go figure.

Speaker 4:This is a long, nine ten page little poem. I went in. I should feel pretty. This is what the commentators say about debbie thomas. I should feel pretty good about myself. Not proud, not invincible, not bad. She's not bad. Why I? I was just okay. How many triples equals feeling pretty good. I am on fire. I'm ready to just be a student again, become a doctor, an intellectual? My soundtrack black excellence.

Speaker 4:Four I'm not beautiful to the watchers, I am the rhythm, the misunderstood. There's nine judges. The highest scores were given to me by what is called the Thompson team, the US and Japan, so they don't count to the watchers. The word beautiful is used dozens of times to describe Katerina with gorgeous, painfully gorgeous, the East German woman is now in vogue. Great eyes, great features, beautiful hair, overpoweringly beautiful. Five Katerina voice. The watchers tell my story. I get thousands of letters from boys. At least one US ice show has offered me millions to skate when I retire.

Speaker 4:The posing section of my long routine was met with great admiration. They say I have a future bright as the sun. She dies at the end, I think. Voice of Debbie Wick continues I wanted her to fall. You don't ever say it aloud, it's horrible to think it, but I did. I wanted her to fall. You don't ever say it aloud, it's horrible to think it, but I did. I wanted her to fall.

Speaker 4:Six maybe your body will just do it. Maybe your body will just do it. Little brown girls take their hot hearts, carry them to the pit of the coldest places. Unrecognizable love travels through their veins. Freight trains abandon passengers, get off on their pain.

Speaker 4:Heart and spirit sometimes grow tired. You just want to skate to win. Heart is tired, spirit is unsure. Maybe your body would just do it. Maybe your body would just do it. Find a way out of the war that was only about love for you. Find your toes connected to spines catapulting you into the next galaxy. You don't feel like showing up. The high five with your coach is off. We missed. Maybe your body will just do it. Maybe your body will remind you. Sometimes skin forgets its layer with flesh stories, bones breaking when simply walking truth and teeth and miles taped shut while speaking. Just skate, just ignore, just pick up your flowers, just be grateful. This body is a landmine full of dividing lines waiting for you to walk over or explode into pieces If you violate its space. Watch the steam rise. Lace them up against the screens. We are all counting on you, debbie. Simplify the fear. It's all psychological. It's too long.

Speaker 3:It's a lot, it's great, it's a lot.

Speaker 4:It is great Okay listen. It's not long at all. Great, okay listen.

Speaker 3:And so, listen, that's why you have to get this book. I should read that poem, you should Look. I made the mistake of watching reality TV.

Speaker 3:The Olympics. How about this? I'm watching Dancing with the Stars. Why am I watching Dancing with the Stars? I've never watched it, but I'm trying to find something easy and simple to watch. And there's this young woman on Dancing with the Stars who can outdance everybody on the show. Not only did she not win, not only did she come in fourth place or third place no, fourth place, whatever she didn't win. But she didn't win because there were people who had TikTok campaigns against her winning, because they said that she had trained at the Debbie Allen School of Dance and therefore she was not qualified to win. She's not the first one, the way they would pick her performances apart. And then there was this man who could do some cool things, but he was not her. She's a beautiful, graceful dancer. It broke my heart. So, okay, fine, Then I made the mistake of watching the Voice.

Speaker 3:Snoop is on the Voice. I'm like, oh, watching the Voice. Snoop is on the Voice. I'm like, oh, I can watch this. Snoop is on the Voice. Snoop has five finalists three black women, one white man, one white woman. He calls the three black women black girl magic. One of them sang Whitney Houston as well as Whitney Houston. One sang Prince as well as Prince, Everybody's mind was blown. One sang Keisha Cole. So he had to pick two people to move on. And he picked the white man, who's first singing Broadway. And then he picked the white woman, not because she was better than the others, because she had the most room to grow. And I felt so deflated I cried. And why am I crying watching television? So deflated I cried. And why am I crying watching television? Because it's just another example of how you can't ever be good enough to be great.

Speaker 4:Come on, Snoop what you doing. I really, and I took that personally, because it was. Snoop.

Speaker 3:And so I know, I understand, and I had to ask myself is he a mascot? Is that what?

Speaker 4:he's doing here. It was already planned.

Speaker 3:I know All of it's just BS, I know it is, but it was just a reminder, and so that poem really hit me where it needed to. It reminded me of how hard it is for black women to be seen as exceptional.

Speaker 4:It's almost like you know, I find us very exceptional because I'm not looking for white people to find me exceptional and I'm definitely not looking for Snoop Dogg to choose me, and so I don't. At the end of the day, we have to. Just I'm in a space where I'm not, I'm exhausted from trying. We know the truth, we do and we know and I know how powerful I am and we are, and I walk in that and I just look to empower myself by it. That's why I build institutions that empower my voice, that lift up other women, because if we don't, no one will, and if someone else does in the process, great, that's the cherry, but we have to do it.

Speaker 3:No, I agree with you, and we do that at ECN as well. We try to lift people. It was my mistake for watching reality TV. I don't even do this, okay. So here I am, thinking I'm going to get in this American pastime and watched reality TV to try to escape from the election and it just doubled down because everything's political.

Speaker 3:Everything is political, and it reminded me of that. But you're absolutely right, we lift each other up. I don't normally watch award shows for that reason, but this poem really meant a lot to me and I just wanted to thank you for it, because you spoke to so much I need to do it, but it's such a long piece that needs to interweave it.

Speaker 4:We need some visuals, or something.

Speaker 1:The other thing too, to Donna's point, and you said in response to her point that you find us you're talking about women exceptional, and that is evident throughout the entire book. I mean, I can't count how many times you invoked.

Speaker 4:And I love brothers too. I know you love us, I know you love us, I'm going to get to that too.

Speaker 1:But I want to talk about your invocation, constant invocation, of intozaki shange in this book. Right, uh, the, the legend, the luminary, sonia sanchez, right, you know, all, all of these luminaries that we I don't know if you, some of you guys, but we had the pleasure of living on this earth at the same time as them.

Speaker 4:And Sonia is here. She's 90 years old.

Speaker 1:These folks mentoring you. Ruby Dee, right, you know all, of all of these folks. You, you speak. You speak the name of black women. Often I do, and emphatically yeah, that's intentional amen, yes and just I.

Speaker 4:I call their names because if I, if not for them, I wouldn't exist. Um ruby d was a goddess when I was around her. I got to interact with her and do readings with her in new york city. And sonia's one of my friends and my mentors who I can call on now and she can answer the phone on the first ring because she's 90 but she's 25 or something. Nikki, giovanni and I have done shows together, but Sonia's like my friend friend. I've known Nikki for a long time.

Speaker 1:I got to interview Nikki before. Oh amazing, she'll say anything.

Speaker 4:She has that no filter thing.

Speaker 1:You do I know, I learned from her.

Speaker 4:So Nikki can say it, I can say it too, but I definitely write choreo poems.

Speaker 2:Choreo poems. Yeah, yeah, I write choreo poems and story right.

Speaker 4:Which is movement with poetry for people who don't know and I'm, which is a big conference that's happening in LA this year, american, is it? Writers and poets? And we're talking. I'm on a panel talking about choreo poems. So Salt City is my one of my choreo poems. That's about Detroit and the future in 3071. But in Tozaki.

Speaker 1:I got to spend some time on it.

Speaker 4:I freaking love that poem, which one.

Speaker 1:Salt City.

Speaker 4:Oh, you mean the whole multimedia piece Shout out to Akuka Dogo. So, Akuka Dogo, my director and choreographer was the woman in yellow in For Colored.

Speaker 1:Girls.

Speaker 4:So she was from the Indazaki Shange.

Speaker 1:For Colored Girls who've considered suicide when the rainbow is enough.

Speaker 4:Such an amazing piece. Right and so. But Salt City. I wanted to write in choreo, but my choreo poem is all Detroit techno. So the work, work of the music of Jeff Mills and Juan Ekins.

Speaker 1:You invoke Jeff. You wrote a long poem for Jeff Because Jeff is Jeff. Yeah, I went to. Paris to see him. Yeah, yeah, yeah, I saw him in Paris. I saw him in Paris. I'll be at dinner. Yeah, I love him so much.

Speaker 4:Yeah, Jeff is and he's got. We got work to do here in Detroit. But him and I people don't know in 2020, me and Jeff Mills and Eddie Folks had a record called the Crystal City is Alive and because it came out during a pandemic, you know, either people knew about it or they didn't, but I've always wanted to work with Jeff. He was on my list with Prince, Like Jeff is a genius, he's a genius.

Speaker 4:And one of my favorite people, and just that poem for him was based on conversations with him and getting to know him and him asking me questions and asking my why.

Speaker 3:He was making me question myself Like well, what are?

Speaker 4:you, but why? But what do you think? And I love he's just so inquisitive and I learned from talking to him. I love learning from people and he's an artist and a friend now that I get to learn from and I hope we have bigger projects in the works. Let me just say that. But Jeff, deserves.

Speaker 1:What's really cool is that if nobody else is writing these people into the world and into history, you are doing so in the most loving of ways. Like from Jeff, I want to talk about your activism. Okay, you know, I don't know if it was Sanchez or somebody who said, like you can't be a poet and not be an activist. I can't remember who said not a good poet not a good poet it may have been amiri, who you also invoke.

Speaker 4:I love I love amiri baraka. I need to say his name a thousand times yeah, but tell me about ferguson after mike brown ferguson.

Speaker 4:Yeah, oh, I can't, yeah. So, yeah, I have a. I have a poem in my book I can't breathe. That's for remembering Eric Gardner and Mike Brown. Yeah, ferguson. So the reason why I ended up in Ferguson was because I was in. I had taught for seven, seven, six or seven summers in a row in the jails in St Louis, and so I knew where Ferguson was. Some of the young people that were in the juvenile detention center where I was teaching at the time I'm doing in residency. I do residencies in jails. I can't get the colleges to call, you know, but I love doing the residencies inside the jails because those kids are going through a transition. I'm saying kids, it is like 16. Some of them are looking at adult time.

Speaker 1:Some of them are closer to 18 years old. Yeah, but they're young people. Stop adultifying our kids, can we please?

Speaker 4:Okay, I would love to. Can we just?

Speaker 1:put a pin there.

Speaker 4:I can't spin that because I want to come back to it, but I went there because I was crazy enough. I was at Mario Van Mario, melvin Van People, the dad, the daddy's house, the OG.

Speaker 4:I was at the OG's crib hanging out with another writer and I was kind of meeting Melvin Van Peebles for the first time and having tea with him and he's just like making fresh orange juice. What an amazing moment. But anyway, and Talib had called me and we had been looking at Ferguson and we went watching the growing, you know, police presence there. That was really disturbing me and I just thought, you know. Then buildings started catching on fire and I was like we need to, I'm sick of looking at this on TV Like we need to go there. So me and Talib and Rosa Clemente, my Puerto Rican sister, Talib Kweli.

Speaker 4:Yeah, me and Talib sorry me and Talib Kweli, the rapper, and Rosa Clemente, you should know, is a hip hop activist and an activist. And so she, we all, met out down there and decided to join the other activists on the ground to say how can we help, what can we do, how do we lend a voice? And so we were like doing ciphers, but we had to learn about, like tear gas and milk in our eyes, and I just didn't expect it to be a war zone and it was. The police presence was so ugly. I had never experienced it. I've been in so many protests and that was the first time I ever felt like I was going to get killed by just being in a peaceful protest. That these weaponized military style police like that side of this I never forget.

Speaker 4:This one white woman officer was like had this huge AR-15 in her hand. She could barely hold it. She was so small and it was almost like too big for her arms. But I could look at her in her eyes and the way they looked at us was such disdain and I'll never forget them saying like go home, go home. And this young brother was like they're telling us to go home, but I live right there. They're at my house. They're in my neighborhood telling me to go home, and so Ferguson hurt.

Speaker 4:But yeah, I got. You know, we got thrown on the ground. You know we literally in a peaceful protest, walking and the the police. What they do is they'll have someone, you know, throw something and then they'll say it was at us, but they'll do it as a distraction to cause some kind of a—to cause confusion. So that, yeah, so that we are dispersed and everyone starts running and everyone's crazy. So a bunch of my friends got beat up by police that night, went to jail that night. We got laid out on the ground, ar-15s at our back, me Kwame, that's what you said.

Speaker 1:I'm being forced to lie face down on the cement in Ferguson with. Ar-15s pointed at my back. Yeah, and.

Speaker 4:I had my babies at home. Man, like what in the hell? I got myself into Ferguson. I'm about to die in Ferguson, you know.

Speaker 3:That was a turning point in so many ways for so many people. I don't know in my family the way it played out was. I remember we were at my sister's house and my oldest was like really just watching. All she did was watch twitter and watch the feed and she was really into that and so, um, she was talking about. My sister said, I just hope the protest is non-violent and that created that, created police art. Well, yeah, and that's my yeah. So, yeah, really fun. Oh, and it became this generational battle, right, because so many people were like invoking, you know, merlin, the king, peaceful protesters and and we were learning. I think people my age were learning. Wait a minute, this is not about peaceful protest. This is about police violence, just like it was in the past and and so having to move away from respectability politics. But I think Ferguson, at least in my family and in my circle, it was a huge turning point. Would you say that there has been more awareness of that since Ferguson than in the broader community since 2014? 10 years, right?

Speaker 4:I mean, yeah, you know, with some of the cameras, some of the cops that I put on cameras now being forced to wear cameras, I think cameras have helped, but it's just helped us see more of us get murdered though I don't think we're getting murdered any less.

Speaker 3:But I don't mean that. I mean more consciousness among black people as a whole, because I feel as though there was lack of consciousness across the board where we weren't really fighting for that in the same way, where we weren't really fighting for that in the same way.

Speaker 4:Yeah, I mean the lack of consciousness in so many spaces it's a lack of education. You know, I think at the core of misinformation is because of our education system being so horrible and so whitewashed and so not focused on the whole person and not focused on lifting up brown and black bodies or stories and how it's going to get even worse. So I think it's just so, it's so layered, and the reason why because I mean I don't know anything else. So I mean I grew up with people that they knew that police were like my mother and father, they were like you know, these are people in the 60s who, like, did march with you know King and came out to see him speak.

Speaker 3:Well, yeah, mine did right. But, then it's like somehow people get anesthetized right and so you know what is it?

Speaker 4:Because the black middle class, you know like, because I was going to say this sounds like more of a class thing.

Speaker 1:The family that I grew up in is well aware of police brutality and what could happen if we say, move or do the wrong thing in the presence of police.

Speaker 3:I think it's bigger than class, though I just want to say, because I've heard people from various things talk about people need to pull their pants up. These kids need to.

Speaker 3:whatever I hear it coming from so many different circles where people will blame young people for not being beat off enough at home or whatever. There has been copaganda going on in our television and our media, so it's definitely a social class, but it's also I've heard so many people blame victims of violence for the violence that is happening to them, people saying that black kids don't love life or they don't care about life, and it always ends up being Well.

Speaker 4:People are not centering it in white supremacy. I remember friends of mine who didn't understand affirmative action. I remember black friends of mine, but they definitely came from big houses. They were not my friends from the poor neighborhoods. And what's about to happen? Possibly with this Department of Education, as much as I know?

Speaker 4:The education system needs to be completely destroyed and reformed. Something needs to happen. But if they get rid of FAFSA and places like that, my son, I won't be able to afford to send my son to private school that he's in. There's no way, without any federal aid, he won't be able to finish school that he's at Like, unless I beg people in this, you know, online for GoFundMe to keep my son in school Like. So this is going to affect so many people, so many people. But as far as like people not being conscious, like I didn't grow up and like Marcus Garvey wasn't on the wall At my, on my, so something was just innately inside of me to know that there was wrong in the world and but I think a lot of it I do believe it is class and none of it is education.

Speaker 1:I think it is. I think God's a divine.

Speaker 3:Some of us are gifted with the divine burden there's some things to see, I'm a seer and to feel, but I think the important thing is also help other people see Right, because if we see, then we have to help other people see. There has been a widespread look when, when, when the police were arresting folks in Detroit during the rebellions. Brenda Jones was talking about how these people were needed to obey the police. And I'm on Facebook arguing with this people who work for the city, people who are part of this, and I'm getting calls from people telling me that I need to tone down what I'm saying and I have so much respect for you and you shouldn't be out here in public spaces. And these are not just necessarily people from a different class structure. I think it is people who are part of the the disconnect is real.

Speaker 3:I think the disconnect is bigger than one group of people and I don't think that.

Speaker 4:And people are getting paid though You're saying it's not class, but people are getting paid to be certain kind of things. The same way we saw black men, like we saw people in Detroit standing up against a fascist and thinking that a fascist, racist, white man, sexist, rapist, criminal is now about to be the president of the United States. Because people align themselves with craziness, exactly, yeah, I mean so. I mean as far, I don't know, I've always known. Yeah, I mean maybe it's just in me and the people that I came up around. We understood that. The police I got surrounded by about seven police, southfield police in Oakland County when I was about 17 years old because I hung out with black men and that happened to me and I'll never forget it and I hate to go to Oakland County to this day and I drove from Novi today to visit my friends who live in the suburbs and every time I'm there I'm like I really don't know why y'all live way out here.

Speaker 1:I need to pack a snack first of all. It's so far. We have about 10 minutes left. I want to switch gears a little bit. Talk about your love In here. You're also really candid about love.

Speaker 4:Yeah, I'm a hopeless person. Are you videotaping this? I got to turn off.

Speaker 2:that Are you the fans?

Speaker 4:Who are you videotaping? Okay, I'm a hopeless person. Are you videotaping this? I got to turn off that. Who are you? Are you the fans? Who are you videotaping? Okay, I'm listening.

Speaker 1:And how. If a poet loves you, a poet loves you forever. Oh yeah. Your love of black men, I'm a.

Speaker 4:Scorpio. So if I don't love you, I probably don't love you either for a long time.

Speaker 2:Yes.

Speaker 4:I love hard. Are I love hard? Are you in love, jessica Caremore, I'm always in love, jessica. I put it like literally yes, during my interdisciplinary show recently. I always put Jessica is always in love, because I'm in love with my people and I'm in love with my community and I'm in love with motherhood. I'm in love with other people's children that don't have moms, that don't have good, cool aunties or somebody to look after. And I need to say this because when I just go back to my event my event there was little white girls in my event, there was little Asian girls in my event, little black girls in my event, and all of them were looking at me like Christmas, like I was like Mrs Claus or something, and so to say that yeah, I'm in love with love, but I always have love in my life.

Speaker 3:You were explicit about it. So, who is Muck Moore?

Speaker 4:Nobody important and so, yeah, listen, they're all just poems. He's a poem, he's just a poem and that's all they are. But I always have love in my life and so love and that's funny because I've been married twice and I'm not interested in marriage um, but I always have love and I'm always and have love in my life and the way I the. What I need in my life as a woman now is different than what other women. Some women need, like a guy in their house every day. I don't need that because I'm not in my house a lot, so I need, um, I date, uh, a man now that has a passport and travels frequently and that works for me.

Speaker 4:I like dads. I tend to date dads. I have dated men of different age groups. I've dated men younger than me. I've dated men my age. I don't date whoever I want to date, but I like being free. But am I in love? I've said that I'm in love with love. I love the idea of love. How can I not? It's like the best thing in the world and I enjoy when I feel it. But I have love in my life and love it was so deep because some of the deepest loves I have in my life are from black men that I've never dated. Wow, oh, these brothers love me.

Speaker 2:I got men that were old. Yeah, we do, yeah, we love you.

Speaker 4:Let me tell you how they would show up for me. And these are not the men I married or I thought I would spend my whole life with. These are my male friends. I'm actually headed to an island next week to meet up with one of my male best friends. I don't date him, he's just my boy, but he was like if you come, I got a villa for you. You know what I?

Speaker 2:mean.

Speaker 4:Like that, and so what I have learned as a woman is that the men I think Eartha Kitt made that. She has that great quote she's like the men that love me the most are the men who never touch me. You know, and I understand that I'm very much walking in my power and I know I can intimidate and I know I'm not for the insecure, and so I know it's not going to be easy for me to find partnership and balance right, and so I might have to find it in different spaces with my male friends yeah, with more than one man.

Speaker 4:I don't know With romance, whatever, yeah, it's whatever I figure and I'm believing I had this conversation. I was with my friends at a cigar bar last night and I smell like cigar, unfortunately because of that. But they were talking about monogamy and saying I was like I believe in monogamy. I don't know if men are really good at it and that's what I do We've never been good at it.

Speaker 4:Yeah, so I don't really believe. When should I be monogamous if he's not going to be? So I'm open to like I like to be somewhere because and the guy that I'm dating actually said that I want to be somewhere because I want to be somewhere, not because I'm obligated to be somewhere yeah, then you got to wear matching pajamas and stuff.

Speaker 1:The only person I wear matching pajamas with honestly, on Instagram would be like would be Plies If Plies wanted to wear oh we like, pl'll be plies if, plies, I want to do, we'll wear.

Speaker 4:I will wear matchy pajamas with plies but no, you know what's cool though?

Speaker 1:because I think, picking up the book, there is an assumption that this is an ode to the bodies of black women, but this entire book is an ode to the black body period. The black body period.

Speaker 4:And it's a book of love poems. It's a book of love poems. They're poems for Ozzie Davis and Ruby Dee.

Speaker 1:There's poems for Gwendolyn Brooks, for Sonia Sanchez. So we gotta head out she done asked me about Muckmore.

Speaker 4:I ain't reading that poem. We don't deserve that poem.

Speaker 1:Take us out. You gotta read something good. I love the Ruby Dee and Ozzie one I do.

Speaker 4:Can I read it?

Speaker 1:It's going to be the love poem since we're talking about love. Yeah, it's in there.

Speaker 4:Okay, so this is called. Y'all Know who Ozzie Davis and Ruby Dee? If you're listening to my voice and you don't know who Ozzie Davis and Ruby Dee are, and let me say this, people don't. And the thing you're talking about the reason why I go back to education, because I was just at Duke University and I've been in Michigan State University in front of very intelligent young people. These young people are not dumb, but they are culturally illiterate and they are going to be future scientists and engineers and doctors, and culturally illiterate scientists and doctors and engineers and lawyers are a problem. Like our future attorneys, you need cultural intelligence Our doctors. Like our future attorneys, you need cultural intelligence Our doctors, so that when you walk Into a doctor's office, or when I walk Into my OBGYN office, there's a conversation that can be had. I would not have A white male OBGYN, ever, never. I prefer a black dentist.

Speaker 1:That doesn't always happen. All of my physicians Are black women, every last one, even my therapist. That's fantastic. Yeah, all of them.

Speaker 4:So sometimes that's fantastic yeah, all of them. So sometimes that's the case. I'm an energy person. If it's good energy, I rock with it. With my son, I've been so protective over who gets to talk to my son about his body, about his health, and most times they don't care about it my son. So I'd love to know who your doctors are, by the way. So I say that to say that we have a lot of work to do, but we have to educate our own communities about who we are.

Speaker 4:And so when I'm in front of kids, when I was at Cranbrook University Cranbrook the school, the high school years ago for Black History Month program, which was so funny, and I was all these white kids I could see all the little black kids sprinkled in at Cranbrook right and I asked them have you ever heard of Sonia Sanchez? Raise your hand. Have you ever heard of Amiri Baraka, raise your hand. Have you heard of Ndazaki Shange, raise your hand? There were nobody raised their hand. And these are. These are the high school students. I'm like, wow, man. And I said your parents. And then I said, well, do you know who Walt Whitman is? And they're like it was a sound Robert Frost. I'm like the same dead white man that I was taught at Cody High School. That's who they knew, and I was like your parents are paying all this money and you're getting half of an education. It's ridiculous, and they're keeping our young people globally illiterate and they don't teach them about the world. Our education system should be a global one, one that shows caribbean writers, caribbean history, like uh and yeah, we're, but why does everything have to study? My, my son was at one of them schools. I was at that. I hated all the schools my son was at pretty much except for dsa and um. Dsa, that's the only one and um and and I struggle with some teachers there too right, it wasn't perfect, but it was better than all the private schools that I pay money to like for trying to destroy my child while I'm paying you to do it.

Speaker 4:My son was in like maybe King was in like third grade and he asked the art teacher they started working on artists why they were. She was starting with Van Gogh. They were starting with Van Gogh and she said well, why aren't you starting with Basquiat or Basquiat? Or why aren't you teaching Faith Ringgold? This is my baby asking about Faith Ringgold and Basquiat. Why are you starting in Europe? Why is that the starting point? It's Van Gogh. Give me a freaking break with Van Gogh. Okay, I went to the museum, he's cool, you know whatever I mean, but that's.

Speaker 4:It's a very. We have a very Eurocentric lens that we, and so we really have to think about black and brown bodies and white people who want to have well-rounded children have to think about the education that we want our children to have. And so if you're listening to this and you are connected to Detroit public schools or the Detroit community district, my book we Want Our Bodies Back should be read in the curriculum at all Michigan schools, at least the Detroit ones. And it's not and it's not, and it bothers me that it's not and I keep talking about it. Real bad, and I have a children's book coming out in June of this year and I need everyone to get Our Crown Shines. If you're an educator or principal, you need to get the book and I'll come to the school. And my girl was like there's like 110. I said I don't care how many schools, I'll come to all the schools. Order the school. So anyway, that to say you should know who Ozzy Davis and Ruby D are.

Speaker 4:Dear Ozzy, dear Ruby. Dear Ozzy, dear Ruby, do you still put roses in her hair? Do you still draw the clouds and fluff them for her head? Is the sun still sleeping in his eyes? Is heaven a place along his chest? Are you resting in a timeless embrace? Do you still make her laugh? Does it still matter? Do you still hold her hands, diamonds hidden inside palms and fingers? Is eternity inside his kiss? Do you tie his tie, adjust his chapeau? Do you dance in the morning? Do Amiri and Maya and Jane and Gil and Sekou visit to drink grapes and share stories? Dear Ozzy, dear Ruby, some of us dare to be the exception, dare to be conductors of black love. Do you still love to be still when the world travels at full speed? How glorious to watch our attempts to become the black doves you became. Do you still fly south for the winter, pick pecans and eat round sweet cherries on the long wooden porch? Dear Ozzie, thank you for your kind words in Harlem when I nervously shared that Abyssinian stage with you. Dear Ruby, thank you for your fearlessness and hard laugh.

Speaker 4:In the lobby of the Schomburg I slapped Denzel Washington, an American gangster. It wasn't in the script, you told me. I could hear your beautiful stutter. She said it just like that, jessica. I slapped him. It wasn't in the script. I could hear your beautiful stutter. Planned pauses landing gracefully on your tongue, eagle Sutter. Plan pauses landing gracefully on your tongue, eagle woman.

Speaker 4:The morning of your funeral, I spent the evening celebrating our sister Sonia Sanchez's 80th birthday. I watched her and Baba Hakeem Madhubuti get in a car headed to Harlem. I was in pain from losing. I was still in so much pain from losing Amiri Baraka. I wasn't ready to bury another legend.

Speaker 4:Forgive me, dear Ruby, dear Ozzy, we know we are possible. We know we can be gazelles on a planet surrounded by wolves. Is his voice the sound of water? Is her smile the perfect moonlight? Do you remember when it was all a dream? Do you still love to get on your toes to reach his nose, kiss his neck? Is she still your Juliet in a spikely joint? Is he still the mare, mother, sister? Dear Ozzy, dear Ruby, thank you for loving us, thank you for loving each other. We marvel in your reflection. Thank you for your life, work, for your voices and bodies as gifts, now that you are true stars. Do you know? You were our greatest wish. So yeah, that's for Ozzy and Ruby, and they are absolutely my dream for a relationship when you talk about love, I've been searching my Ozzy Davis for such a long time and I don't know, maybe I found him.

Speaker 4:You never know. You never know, it's possible.

Speaker 1:Jessica Caremore. Thank you for coming on Authentically, Detroit.

Speaker 4:I will come anytime. We love having you here. I hope it was enough. It was great.

Speaker 1:Okay, great, it was great, and our bodies back it's available everywhere. It's available everywhere. Stop by Next Chapter Books and or Source Booksellers to get them. Support Black Bookstores, y'all, please. If you have topics that you want discussed on Authentically Detroit, you can hit us up on our socials at Authentically Detroit on Facebook, instagram and Twitter, or you can email us at AuthenticallyDetroit at gmailcom. We thank you so much for listening and until next time, love on somebody and allow yourself to be loved on Outro Music.