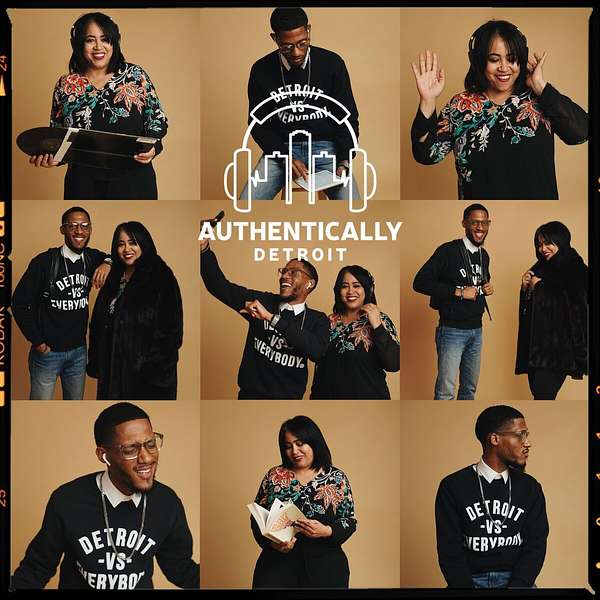

Authentically Detroit

Authentically Detroit is the leading podcast in the city for candid conversations, exchanging progressive ideas, and centering resident perspectives on current events.

Hosted by Donna Givens Davidson and Orlando P. Bailey.

Produced by Sarah Johnson and Engineered by Griffin Hutchings.

Check us out on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter @AuthenticallyDetroit!

Authentically Detroit

Breaking the Silence: Supporting Black Survivors of Sexual Assault with Kalimah Johnson

TRIGGER WARNING: This episode contains sensitive, potentially triggering themes and language related to sexual assault. Listener discretion advised.

This week, Donna and Orlando sat down with Kalimah Johnson, Founder and CEO of the SASHA Center, to discuss how they are supporting and empowering Black people who have experienced sexual assault.

At the SASHA Center, Kalimah’s mission is to increase awareness, provide resources and educate the public about sexual assault, provide culturally specific peer support groups to self identified experiencers of rape and to increase justice and visibility for survivors in Southeast Michigan.

Kalimah is a highly esteemed expert therapist who has made a significant impact in the field of mental health and relationship counseling. She has been an advocate and counselor to survivors of sexual assault and intimate partner violence for 24 years and is an industry expert on topics related to culturally specific programming for sexual assault survivors.

To learn more about Kalimah, the SASHA Center and their work, click here.

FOR HOT TAKES:

DETROIT ANNOUNCES NEW ‘EMERALD ALERT’ FOR SERIOUS MISSING PERSONS CASES

Up next. Kalima Johnson, founder and CEO of the Sasha Center, joins Authentically Detroit to discuss how they are supporting and empowering Black people who have experienced sexual assault. But first this week's hot take from the Detroit Free Press Detroit announces new Emerald alert for serious missing persons cases. Keep it locked. Authentically Detroit starts after these messages. Network are for studio space and production staff. To help get your idea off of the ground, just visit authenticallydetcom and send a request through the contact page. Hey y'all, it's Orlando. We just want to let you know that the views and opinions expressed during this podcast episode are those of the co-hosts and guests and not their sponsoring institutions. Now let's start the world. Welcome to another episode of Authentically Detroit broadcasting live from Detroit's East Side at the Stoudemire inside of the East Side Community Network headquarters. I'm Orlando Bailey.

Donna Givens Davidson:And I'm Diana Gibbons-Davidson.

Orlando Bailey:Thank you for listening in and supporting our efforts to build a platform of authentic voices for real people in the city of Detroit. We want you to like, rate and subscribe to our podcast on all platforms, and today we have a very special guest, kalima Johnson, founder and CEO of the Sasha Center, here to discuss how they are supporting and empowering black people who have experienced sexual assault for the first time ever. Kalima, welcome to Authentically Detroit.

Kalimah Johnson:Well, thank you for having me and what up dog.

Orlando Bailey:What up, dog Donna, you were on vacation last week. I had to fly solo. How was your vacation? How were you doing? It's good to see you.

Donna Givens Davidson:I called it a fake-cation because I kept working.

Orlando Bailey:This woman was calling me. I'm like, why am I still working If you keep calling me? Call your therapist.

Donna Givens Davidson:I really need to right, Because I just kept working. I will be taking a real vacation later this year celebrating our fifth wedding anniversary, but we had our fifth wedding anniversary on Friday. And so that was fun, and yesterday we celebrated all weekend doing different things. But yesterday we went to Kensington and went bike riding on the Kensington trails. There's absolutely no better place to ride bikes than Kensington.

Orlando Bailey:What body of water is that?

Donna Givens Davidson:It's Kensington Lake.

Orlando Bailey:Kensington Lake. Yeah, yeah, so it was a great time. I'm still Five years A COVID wedding.

Donna Givens Davidson:COVID wedding, right. So COVID wedding, you don't take a honeymoon, right? Right wedding, you don't take a honeymoon, right. So we're doing it this year, and so even though it was kind of a fakecation, I did get some rest and that was needed and I'm back.

Orlando Bailey:Welcome back. It is the top of the week and it's sunny, but when you walked out the house first thing this morning, you probably wanted to go back in and get a jacket. It's like, oh my God, it's summer ending. Halima, how was this day finding?

Kalimah Johnson:you, it's finding me well and I'm just so glad to be here, and I want to share what I did this weekend. I actually married a couple. Oh wow, I am an officiant and it was an awesome thing to gather Benita and Sean's family together and I just had a great time. It was good to see, like I know, sean. Actually, sean participates in volunteers at the Sasha Center and his wife, now Benita, also does as well, so I got a chance to spend some time with them and some of the work that we do at the Sasha Center. But then being able to be in space with them with family, was beautiful, that's amazing.

Donna Givens Davidson:Yes, I love love. There's nothing like being married by people you know. So, my sister, who's a judge, and my childhood friend, who's a pastor, co-officiated our wedding, and it was personal, because when you're marrying people and you love the people that you're marrying, it's a different kind of environment.

Kalimah Johnson:Oh, I was so on high. It was a beautiful feeling and I just felt like I was getting married.

Orlando Bailey:Oh, man, I love it. Love is in the air.

Donna Givens Davidson:Yes, and we need more love in the air because all of the anger and all of the other things that we're feeling, and love being stronger than hate, when we spread love. We understand that that is resistance because, hate is what we're supposed to do. So I resist, try to resist with love. I'm not good at it all the time, but I try to do that. Where was the wedding?

Kalimah Johnson:It was in Westland at a banquet hall called Emerald and it was really nice. It was just, it was really quaint, it was just their family and everything, but it was. It was I was honored to be there. And it was something else that was very interesting. The last time I married a couple, I married a couple in Atlanta and they had the exact same color palette and I said y'all got the same color palette, what else do y'all have in common? So the bride that I married on Saturday and the groom that I married a couple of years back, they both went to the University of Michigan.

Donna Givens Davidson:So you can imagine what the colors were Green and white, green and white.

Orlando Bailey:I'm just wondering you guys are insufferable, I know right, but you know what we need more love, we need more community and we need more Afro beats. Because I don't know about you, but I was at the Afro Future Fest this weekend, all gussied up for festival ready. Listen, it was fun. It looks like so much fun. It was a fun time. I didn't know what they were saying half the time, but it's not about what they're saying, it's about just moving and grooving to the music. I hung out with David and Camille. The parents were out, yeah they were Okay.

Donna Givens Davidson:So here's a true story. They wanted us to babysit yesterday when they went back to.

Orlando Bailey:Afrobeats right. Yes, yes.

Donna Givens Davidson:And so my husband was like, Kevin was like we're not doing that, we will not be back in time. It is our anniversary because we did watch Maverick and Steele the weekend before when they went to a wedding. And they were like no more weddings, no more babysitting.

Orlando Bailey:This is our time, donna. This is our time, and.

Donna Givens Davidson:I felt a little guilty about it, but I'm glad that you guys had a good time.

Orlando Bailey:We had a blast.

Donna Givens Davidson:Listen. On Friday I went to this event at the DYC. Eddie Folks was.

Kalimah Johnson:DJing.

Orlando Bailey:Yeah.

Donna Givens Davidson:And it was great.

Orlando Bailey:Yeah.

Donna Givens Davidson:But my knee is so messed up. I was trying to dance. Oh my goodness, Afroats just looked intimidating, because everybody was just moving and standing up. I was like wow, I mean, the videos look great.

Orlando Bailey:I mean it was just a good time. Black people are so gorgeous, oh my God. Just everywhere you looked you just saw somebody. You know some people, you knew people to meet. It was just a really familial gathering everybody, no problems whatsoever.

Donna Givens Davidson:yeah, no problem most of the time we come together, we don't have problems, and I think, that doesn't always get talked about yeah every once in a while there's something, but I think what I love about afro beats afro future afro future, afro beats music.

Donna Givens Davidson:The whole theme is bringing black people together across the diaspora to celebrate and find commonality with each other. There is so much division going on. You know were you born, are your grandparents? Are you descended from slavery? Are you descended from somebody else's place else where they had slavery, or are you descended from someplace else that was colonized and oppressed? I mean, the reality is that we share some heritage.

Donna Givens Davidson:We do and we come together and we celebrate that. That really makes us, I think, stronger worldwide. So I love the idea of it, even though it's probably not for my demographic right?

Orlando Bailey:No, your demographic was in the house. Don't say that they had better knees.

Donna Givens Davidson:Okay, because I couldn't hang.

Orlando Bailey:Listen, let me tell you one of the ladies was in the assistant thing that helps her walk, that you can also sit in. I don't know what the official name of that is called. I'm going to use Walker for lack of a better phrase, but she was out, she was having a good time. You don't need that.

Donna Givens Davidson:I'm not saying you need that, orlando Bailey. You already know, you know me and you know if I'm out in that I'm home because I'm never going to be allowed to be on that.

Orlando Bailey:But no, but they also had some seating and stuff. I know it was a good time. Shout out to Otto at Bedrock for making it happen once again, and shout out to my friends David and Camille. I saw them and they were together. I said I see why y'all keep making people, because y'all are two people that love it. They just so oh, googly-eyed and in love. It's so cute. I know it is cute. It's so cute. They're all engaged. I'm excited. I'm excited for them.

Kalimah Johnson:All right, All right Well my one jam from that genre is by Ja Praza Dangerous.

Donna Givens Davidson:And I can just listen to it over and, over and over again.

Kalimah Johnson:I don't know what they're saying and you get up and you move.

Orlando Bailey:It feels good. All right, y'all for high takes. Detroit announces new Emerald Alert for serious missing persons cases. Speaking of Emerald right and we're talking about an Emerald Alert this is to the color of the iconic Spirit of Detroit statue. Detroit Police Chief Todd Bettison and Council President Mary Sheffield announced on Monday, august 18th, an Emerald Alert will be sent out for missing children under 10 who've not been seen by any adult for an extended time, missing persons with special needs, non-domestic adult kidnappings and cases where foul play is suspected. The Emerald Alert system will also send out Amber Alerts.

Orlando Bailey:Both Bettison and Sheffield said serious missing persons cases are a top priority in Detroit and they said, when it comes to locating them, every second counts. Here's the quote the Emerald Alert is about making sure that when someone in our city is missing or in danger, we act quickly and do everything in our power to bring them home. Sheffield said it's about making sure that when a child, a senior or anyone in our community goes missing, that we are acting with urgency, with compassion and determination. Again, every second matters and every Detroiter matters. Sheffield said the Emerald Alert was designed to meet the realities and needs of Detroit families.

Orlando Bailey:The criteria for Amber Alerts have long been criticized by experts and family members desperately searching for loved ones. The Amber Alert plan in Michigan began in 2001 and is a partnership between law enforcement and the media to immediately disseminate information to the public about an abducted child using emergency alert systems. It expanded to freeway message signs in Metro Detroit and Grand Rapids a year later, according to a 2002 Free Press article. Chief Bettison also acknowledged those difficulties surrounding Amber Alerts on Monday, and experts have also pointed out racial disparities. Bettison said the community has felt it, especially among Black girls and, considering Detroit is a majority Black city, the community has said we need to do more. So this is a response to be able to do more.

Orlando Bailey:Pedersen said Detroiters can sign up for Emerald Alerts by texting Detroit Alerts 365 to 99411. That's it Detroit Alerts 365 to 99411. Alerts come in English, spanish, arabic and Bengali. The alert will provide the name and description of the missing person and where and when they were last seen. If Detroiters have a tip about a missing person, they can call 833-7297. Again, 313-833-7297. Donna, what?

Donna Givens Davidson:say you. I'm excited to know that we're doing something about it. It speaks to you know. The disparities that exist are that when you have a child who's classified as a runaway, that child does not qualify to be featured in Amber Alert, and we have the adultification of black children. Black girls we're going to talk about this with Kalima a little bit later, right but the adultification means that we make the assumption that black girls who are missing are making choices, even though we know that there are so many crimes against black girls inside of our community.

Donna Givens Davidson:Sex trafficking is a big issue inside of our community. Nonetheless, there is this hesitancy sometimes to look at black girls as victims of the violence that surrounds them in a lot of instances. So providing that focus is important. We know how many I mean I don't even like to think about how many black girls are currently missing in the United States, but quite a few, and in our city quite a few, and so I think it's great. Hats off. I don't know who initiated that, but Todd Bettison and Mary Sheffield. Hats off to both of them for at least bringing this to our attention.

Orlando Bailey:You know, as a member of the media, I get media alerts from the city of Detroit and the Detroit Police Department and every day, all day, like clockwork, we get media notices about missing persons, and it's been going on for years. I've been getting these alerts and when I was at Bruce Detroit, I wanted to figure out how we can erect some sort of a series on all of the missing people young people, older people, people with special needs that go missing in the city of Detroit, because it is rapid and it is circular.

Orlando Bailey:And one of the pieces of feedback that I got is that because it is so rapid and because the only way we know about missing persons is through a media alert and not some sort of a dashboard, we would have to hire at least two bodies, two people, to manage that kind of series on a website.

Donna Givens Davidson:That's scary.

Orlando Bailey:Right, and so my hope for this new alert system is that there is some sort of data portal that news organizations can pull from so that we can deliver uh stories or alerts in real time as we get them. The other thing, too that was also uh, um, a little that was also crazy is that, and we would have to have someone managing all of the reports of missing people. But what we also get and this is also a piece that nobody really talks about we also get press releases from the Detroit Police Department about how they have recovered these missing people. Right, there are so many recoveries Right, and so more.

Orlando Bailey:I have to ask the police chief what the recovery rate is for the city of Detroit. But just anecdotally, for me, from what I see, it's high because the police department, as Mary Sheffield said, the first couple of days, the first day, is very, very critical, and in many instances I'm getting recovery notices the same day or like the day after, and so, to the extent where I know the city has some kind of technology where they can sort of load and feed a portal of data that updates in real time, I think it would benefit, like a news organization like Bridge Detroit who wanted to do it and couldn't, or even outlier media. I haven't brought this idea to Aaron Perry, so this is just an idea Aaron controls that side of the house but so that community oriented publications that actually reach the audience that these missing alerts need to reach can be a part of getting the word out and reporting on the recoveries as well.

Donna Givens Davidson:You know, we, as you know, have a pipeline newsletter and we now have a circulation of about 6,000 people. It would be, useful for us to also incorporate that in our circulation. So if you look at nonprofits that shoot out weekly or you know however often newsletters, I think figuring out how to way to a way to share that information.

Orlando Bailey:Because we're literally getting PDFs. That's how they send it. They send it in a press release, in a PDF, and the way we get.

Donna Givens Davidson:It is like you know Facebook post and a lot of the Facebook posts it's like this person is missing in Alaska and they were found last year and so people sometimes are highly skeptical of the post they read. I think really making sure you're localizing the information is important. But, kalima, I know we're going to talk about the Sasha Center, but before getting to the Sasha Center you worked as a social worker for the police department.

Kalimah Johnson:I did. I did in the 1990s. That was my first professional career position after I graduated with my master's degree in social work. Just a little bit of history about that. It was called the Rape Counseling Center. Rape Counseling Center was actually created as a result of a rash of school girl rapes. That was happening in 1974 and 75. The first person that wrote the grant to get the money was Mary Ann Mahaffey, and her and Barbara Simon actually wrote the grant to open up the Rape Counseling Center, and their first intern was the Honorable Alberta Tinsley Talabi, and then their director of the program for many years was Althea Grant, and then their director of the program for many years was Althea Grant, and when I came to the Rape Counseling Center, it had already been running for about 20 years.

Kalimah Johnson:Luckily, I was able to be around some really powerful women and men who were actually doing the work. What was really interesting about the Rape Counseling Center, though, is that it was the only quote unquote nonprofit-like RAN department within a city entity. It was not happening anywhere in the country, and when I became a social worker for the Detroit Police Department and when they got more funding in the 90s, I was one of the first social workers to integrate, to actually work in the precincts with the officers side by side, and I did that for 10 years and that's where I got a notion, or learned a little bit about how we move in Detroit when it comes to trauma, when it comes to relationship, safety and management, when it comes to domestic violence and sexual assault, and that also fueled my commitment to create the Sasha Center. But when I was with the Detroit Police Department, all that time I learned a lot about, you know, at the time I was there.

Kalimah Johnson:The one thing that happened, which was unfortunate, but thank God we solved the problem later but I was standing there and I would carry a pager and it would go off Like whenever a sexual assault would happen in the city of Detroit, it was automatic that any EMT, police or whoever would have to take them to DRH. You had to go to Detroit Receiving Hospital. It's not like that now, but I would carry the pagers. So whenever they would bring a rape victim into or domestic violence victim into the emergency room, I was one of the folks that would have the pager on my shift and what I learned is that there was a notion of urgency depending on who they were serving and that kind of. I used to have to ask for supervision about it and everything. But I figured it out that black lives are just not as valued, and that's not just by a particular group of people, but just that black life in general is not as valued as it could be, even by black people.

Donna Givens Davidson:That's exactly what I'm saying. So I can't wait to get into your background. Orlando's going to say some introductory things. Yeah, because I can't wait to get into your background.

Kalimah Johnson:Yeah, I know we're going to Orlando's going to say some introductory things. Yeah, because I can go. No, no, I mean you have a lot to say.

Donna Givens Davidson:Yes, I'm really excited about having this opportunity to speak. We can correspond over Facebook, but two things I hope that you talk about. One of them is your history as a young rapper, because while you were I would imagine either before or during the time you were working for the police department you also were involved in local hip hop.

Kalimah Johnson:I was definitely before Before.

Donna Givens Davidson:Okay, all right, so one was-. I was a hip hop artist first Hip hop artist first, but also you also have another kind of business that you operate in, Actually a couple more. You officiate weddings and you also do some things with people's hair.

Kalimah Johnson:I do. I'm a loctician and I have my own studio. It's called the Pignap Natural Hair Care Studio and I've been cultivating locs now for the past 30 years.

Donna Givens Davidson:Yep, so that's Authentically Detroit too. I wish y'all could see this woman, because she don't even look old enough to be doing something for 30 years, but that's neither here nor there, thank you.

Orlando Bailey:If you have any stories that you want us to cover on Hot Takes, you can send us a note at authenticallydetroit, at gmailcom, or you can hit us up on our socials at Facebook, instagram or X. At Authentically Detroit, kalima Johnson is up next. We'll be right back. Detroit One Million is a journalism project started by Sam Robinson that centers a generation of Michiganders growing up in a state without a city with one million people. Support the only independent reporter covering the 2025 Detroit mayoral race through the lens of young people. Good journalism costs. Visit DetroitOneMillioncom to support Black independent reporting. Interested in renting space for corporate events, meetings, conferences, social events or resource fairs? The MassDetroit Small Business Hub is a 6,000 square feet space available for members, residents and businesses and organizations. To learn more about rental options at MassDetroit, contact Nicole Perry at nperry, at ecn-detroitorg or 313-331-3485.

Orlando Bailey:Kalima Johnson is the founder, ceo and executive director of Sasha Center in Detroit, michigan. Prior to creating this organization, she was a sexual assault and domestic violence social worker for the Detroit Police Department, being one of the first civilians to integrate into this role, working alongside police officers to advocate for people who experience interpersonal, traumatic, violent crimes. She was also a full time tenure track professor at Mary Grove College, teaching interpersonal and community social work. Currently she is a consultant and content expert to the National Basketball Association. Y'all heard that the National Basketball Association on matters of relationship safety and management At the Sasha Center.

Orlando Bailey:Her mission is to increase awareness, provide resources and educate the public about sexual assault, provide culturally specific peer support groups to self-identified experiencers of rape and to increase justice and visibility for survivors in Southeast Michigan. Kalima is a highly esteemed expert therapist who has made a significant impact in the field of mental health and relationship counseling. She has been an advocate and counselor to survivors of sexual assault and intimate partner violence for 24 years and is an industry expert on topics related to culturally specific programming for sexual assault survivors. I mean I wish you guys could have heard the conversation before this conversation we were getting ready to have. I almost wanted to tell our audio engineer to hit record as I was prepping the rundown for today's show, because the conversation between Donna and Kalima was just so rich. We're really happy to have you here.

Kalimah Johnson:I'm happy to be here.

Orlando Bailey:You have done so much I'm not done and you're not done at this very moment. How does it feel to be you?

Kalimah Johnson:Listen, I feel satisfied. I feel like I am doing exactly what I'm supposed to be doing. I feel aligned with the universe and with my people and I am just really humbled by every experience that I have. And this year in particular, I was really intentional in my prayers for the new year. I specifically asked the universe, God and all the things that are powerful to present opportunities for me to have a chance to talk with and among black folks about sexual assault and what it means in our community and how we can start addressing it and how we can help our community heal. So and it's been happening. I mean, I'm right here, I pray for this, so I'm just glad I'm here.

Donna Givens Davidson:Oh, we're glad to have you.

Orlando Bailey:Yeah, what's the Kalima Johnson origin story? How would you tell that story?

Kalimah Johnson:Oh, my story. I grew up on the North end of Detroit, goodwin and Westminster, and I was raised by a single mother. I have two sisters and my mother not only was a single mom, but she was raising us with mental health challenges as well. But she's very resourceful. And my two sisters beside me you think I'm a powerhouse. They are powerhouses. I'm learning from my little sister as well as my oldest sister, and I will say that I remember telling my mother when I wanted to be a rapper, I had decided that I was listening to the song we're Going Funk. You Right On Up with Angie Stone, and Angie Stone was the emcee first. If y'all don't know, I'm just saying I'm talking to musical people. I can tell it, I can feel it.

Kalimah Johnson:But anyway, I remember learning one of the verses of Funk you Right On Up and I could feel it. But anyway, I remember learning one of the verses of Funky Right On Up and once I memorized it I put my mom and my sisters in the living room and I recited it and I told my mother I want to be a rapper and I'll never forget what she told me. She said you are what you say, and if you can't say it in this living room in front of me and can't say it outside, wow, she was intentional. She was intentional Because, first of all, even as a young person, I had a very hot mouth right, and I was always going to say something. I was always concerned about fairness and justice and I would say things. And so I remember my mom would also. She could pick up if I had a bad day at school and she'd put on Nina Simone, mississippi, goddamn. And she, she. Let me sing it as hard and as loud as I wanted to, and I think that's my origination story that I'm going to sing it. I'm going to say it as loud as I need to, especially when I see injustice in our people, especially when I know that there's information that I've learned through trial and error that there are more things that we could be saying about healing from sexual abuse and assault. I'm also a survivor of sexual assault. There are more things that we could be saying about healing from sexual abuse and assault. I'm also a survivor of sexual assault. I was sexually assaulted by a family member as a child, then I was sexually assaulted again in the context of a first date, and then I was sexually assaulted again by a so-called boyfriend. And all of that happened before the age of 20. And so in my struggle Compounded. Oh yeah, on top of that, there's research that proves that if you've experienced a sexual trauma very young, it is likely that you will experience it again, including domestic violence, later on in life. And then another thing I wanted to bring up too, when I heard you all talking about what's happening in the loop around with the police. I need you all to understand and know. There is a group that I work with called the Ujima Community, and they are a research hub in the United States around Black women and girls and sexual assault. And then, of course, the actual research that Georgetown did on the adultification of girls is something that we really lean into very hard as we're doing this work. So I'm glad you brought that up earlier. But one of the things that they discovered in the research is that out of 15 black girls who are sexually assaulted, one will make a police report.

Kalimah Johnson:One and one of my lived experiences in working at the police department, that was my first real job, but even before then I would always tell people hey, I'm going to get my degree and I'm going to work for the city of Detroit, because the city is in my blood, the city Detroit. I love this city. I could go a million miles away and come back and still love this city brand new, Right. So, um, I knew I wanted to be a city worker and so I was really happy to do that. But in that I learned a lot. I learned about how systems treat black people. Um, I learned about how, you know, I was actually holding the hands of victims of sexual violence, thinking that holding their hands while their rape kits were being collected, only to be found later after I had left the job. I think that was in 2008 that we discovered it. I left that job in 05. And in 08 was when we discovered that those very rape kits weren't processed, weren't tested weren't investigated.

Kalimah Johnson:And they were found in a building, weren't tested, weren't investigated.

Orlando Bailey:And they were found in a building.

Kalimah Johnson:But please know please know that those rape kits were in a building that was being torn down. It wasn't just sitting in a building later to be seen, that building was in the process of being torn down when they discovered it. And that broke my heart, because I remember not just how hard the police officers and everybody worked, because you got to hold this with both hands. You would have a police officer who would do all the things that they needed to do appropriately, correctly and with respect and with dignity. And then you would see police reports where officers literally wrote down this heifer is lying.

Orlando Bailey:My Lord.

Donna Givens Davidson:And so I want to stay there for a minute, because you talked about, you know, one in 15 women who is a survivor of rape who have been sexually assaulted, and I'm one. Right, I didn't tell anybody. You know, it was one of those things that's never not stayed with me. But prior to me not telling anybody that there were several instances, this is when I was in college at U of M. Go blue, you know, for whatever that means. But I was in college at U of M and on several occasions when I was being sexually assaulted and I told people, they laughed it off and said, oh, and the person who assaulted me was a white man or I don't know. There's a couple white men and they invited my boss, took me to this party and they offered us a drink and I woke up in the car crying.

Donna Givens Davidson:I'm so sorry that happened to you and then she quit her job and then called me back later and apologized. You know so. But you know, prior to that and in Ann Arbor there were a couple of instances where white men would grab me, you know, inappropriately. And I tell people and they say, black people, he doesn't want you, you're black, why would he want you? And I heard that so often that it taught me that my body did not count and my body autonomy did not count. So I walked, I was angry. You know I carried a lot of anger with me and fear of white men and I don't know if that's gone away yet. That's fair. There's a fear. That's there, the dehumanizing fear that you see me as an object. And then when you read about Rosa Parks and you read about what she was doing in the South, Well, wait a minute, let's make sure that your listeners know and hear that.

Kalimah Johnson:And first of all I want to say I'm very sorry to hear you have to share that particular experience, but and I won't say but I will say, and you are telling the story of so many who have never.

Donna Givens Davidson:That's the reason, and that's the reason I shared.

Kalimah Johnson:Yes, never, ever feel compelled to share. But a lot of people don't notice about Rosa Parks. She was a rape advocate first, yeah, and she did that with the NAACP and she checked on Recy Taylor. But she didn't just check on Recy Taylor, like she went down there and the sheriff chased her off the porch with guns and she went back at least two other times to bring attention to how black women were being treated.

Kalimah Johnson:But we literally need to look at and I want to encourage us to think about this as well is that sexual trauma is embedded in our experience here in this country. So, like when I talked about earlier, before you started the recording about how we've never had the chance to really unpack the meaning of lynching and how that has impacted black men today, we also have not unpacked the fact that black women's bodies were commodified and that black women's bodies were made to make more slaves and that there were no laws that literally protected us. And I don't care how many lynchings happened in this country, there was never one for the rape of a black woman.

Donna Givens Davidson:There's nothing on record for that I mean because it was not illegal. Black women's bodies did not belong to black women.

Kalimah Johnson:Absolutely.

Donna Givens Davidson:And you know black families had no right to anything, and you know, but fast forward. And you know, even today there are some black girls and women who can be raped, who can be assaulted, and their bodies still don't belong to them in the legal sense, because if somebody can do this, like you can say rape is illegal.

Kalimah Johnson:There's an automatic assumption that black women's bodies don't matter and that black women are not believable and that these are the stereotypes that black women have to carry. I really want to take a turn, though. I want to turn.

Donna Givens Davidson:But I just want to just point out yeah, the arrest rate, when women report rape, the arrest rate is exceptionally low, the prosecution rate is exceptionally low and the conviction rate is abysmal. And so when people say why didn't you tell we are living in a nation where very few men actually get convicted of raping women, isn't that the truth?

Kalimah Johnson:Yes, and I'd like to offer you a tool.

Kalimah Johnson:And that's why I said let me take a turn, as we're having this conversation. So at the Sasha Center we've developed an infograph and the infograph is an actual picture that explains why black women do not disclose. It is called the lived experience decision tree and you can find it on our website If you go to wwwsashacenterorg, and it explains all of the barriers that black women face as they do try to disclose. And one of the things I really want to be clear about when it comes to the Sasha Center if you decide not to disclose at all, if you decide to just keep it to yourself and find your own resources and community, that is fine. If you decide that you want to file a police report and press charges, that is fine. If you decide that you want to tell your friends and family, that is fine. You want to tell your friends and family, that is fine. But always remember that you have to hold those things with two hands because you don't know how people are going to react or respond other than yourself. And one of the main things that we want folks to know that it doesn't matter if you report or not, it doesn't matter if you tell your family or not, it doesn't matter if you've just only acknowledged it to yourself.

Kalimah Johnson:Sasha Center is the soft place to land, because we understand and know that these dynamics exist. And these dynamics exist because of patriarchy, because of white supremacy, because of power and control dynamics. And we live in a community, we live in a society that is so quick to victim blame. And what victim blaming is about is, if I find the one thing you did wrong, I don't have to help you. And if I also identify one thing you did that I would never do, then I feel safer. I'll say it again, because I really want you all to hear this If I can say you shouldn't have been out that late, you shouldn't have been drinking, you shouldn't have been with them, you shouldn't have been out that late, you shouldn't have been drinking, you shouldn't have been with them, you shouldn't have been at that house, you shouldn't have did this, that that, that that all this litmus of things. If I tell you you didn't have to see, you did that. So because you did that, now I don't have to do anything. Because you asked for it, you wanted it. You put yourself in a position to and we're not challenging enough the people who are committing these kinds of acts and crimes.

Kalimah Johnson:Now, at the Sasha Center, we don't focus on perpetrators. That's not our job. That was never our job. That was never what I created Sasha Center for. I created Sasha Center so that people could have a place to process, to integrate, to live, to get back into their bags, to know exactly what it is that they're supposed to be doing with their lives, so that they can actually be happy and whole, even in spite of anyway. Now, that's resistance, right. And so the other part about this victim blaming piece is if I can identify something I know my daughters would never do, or if I can identify something, oh, I would never think about that. I would never use a dating app. I would never. If they do all of that, then that makes them feel safer, but quiet as it's kept. None of us are safe. It can happen to any of us. And I'm going to tell you something else when we're engaging brothers, black men, men will say you know, I got my first piece when I was 10 or 11.

Donna Givens Davidson:No, you didn't.

Kalimah Johnson:You were raped and I'm so sorry that happened to you. If the babysitter did it, the cousin, the auntie or the teacher up the block or somebody I have worked with professional athletes, football players looking at me like Kalima what size did you think I was when I was 11? I was this size at 11. What do you think happened to me?

Donna Givens Davidson:Right, you know, I talked to one of our friends, mutual friends on Facebook, challenged me and told me about the number of young black men, boys, who are raped or are raped by babysitters, by older black girls, and I was like that's not true. And then I looked it up and I was like that is true, wow. And then you, I've worked with young men and I've talked to other people where grown women will hit on, you know, little boys, on teenagers.

Kalimah Johnson:Right, and our challenge at the Sasha Center is we're really trying to create safe spaces for men to be able to process that, because once they can process that, then they can have a conversation about their own safety and then they can also have conversations about the safety of the women around them. And so one of the other things I think is important as we talk about all these things is, like I said, there is a tool right there for you all to understand. At the end of the day, people can make decisions about how they are healing from sexual abuse and trauma. And I'm going to tell you something Black people have been healing for a long time. No one has asked them how, and that's why we created the Sasha Center.

Orlando Bailey:Wow, can you talk about the reframe into making sure that the process for healing and choosing how to heal is centered on oneself and not the perpetrator, because in many regards the perpetrator is, it looms large, the shadow of this perpetrator looms very large in the life of a victim. How does that reframe and recentering work in practice, like in action?

Kalimah Johnson:Listen, it is so exciting to be able to reframe with the communities that come and that we serve communities that come and that we serve. The first thing that we actually do at the Sasha Center is help define what rape is. So when we first started at the Sasha Center and we said we were going to have these support groups for those who have experienced sexual trauma, nobody came. We did it at Mary Grove in the basement at the Women's Center. That was the only space I had access to. No one came.

Kalimah Johnson:A few people called, put another sign out, hey, we're going to have these groups Sending out emails, doing all the things whatever we could use at the time. And we got like five or six calls and the calls were I know somebody who need to be in your group. Then we had to change our structure and say well, can you bring them? We about to hear you toughing this. Now it's hard to explain this to funders, but we do it anyway because we know how we are in the black community, right. And so come hell or high water, right. We open the doors, we get maybe seven or eight people and four of those people are bringing somebody. But then when we sit down and literally put words and language and feelings and emotions and experiences together to define collectively together what rape is, what is the lack of consent, how and where and when it happens. Everybody in the room is like well damn, I'm supposed to be here anyway.

Kalimah Johnson:Oh lord, and so that's what we know. And the other thing that we know is that wherever Sasha Center gathers, wherever we are, if there are black people, somebody got a story. We know that and that's unfortunate, but it's real and that's how we move. Doing to heal oh, you've been writing songs. Oh, you learned an instrument. Oh, you write poems. Oh, you like to hula hoop. Oh you're drawing. Oh you're listening to music. Oh, you're talking to a Reiki master. Oh, you got a voodoo priestess on your side. Okay, that's what's up. Oh, you pray Okay, that's what's up. What else you doing.

Kalimah Johnson:Oh, you do hair. Oh, okay, that's what's up. Makeup, all makeup, all the things that make us who we are aesthetically. That you saw downtown during Afro Future is the Sasha Center, and we allow people to bring those things with them and we don't say we know a better way. We say we want to learn your way, and then we want to bottle it and then we want to make sure that we spread it so that other people can experience that acceptance. Spread it so that other people can experience that acceptance, that love our culture, and we don't turn people away. I really want to be clear about that too.

Kalimah Johnson:At the Sasha Center, anybody can come to our support groups, however they identify and however they were born. But what we do is we center the lived experiences of black women and girls, which means that while we're in the middle of a session, something might come up about slavery, something might come up about George Floyd, something might come up about chitlins. We're not going to stop and explain it to you you got to go Google later Because we're centering this experience. So, to answer your question, I think the way that we visit in helping experiencers, because we don't call them survivors or victims that's something else we had to learn, because when we start calling people survivors or victims at our agency I can't speak for nobody else when we start calling them victims and survivors, then we set up a whole notion of how they're supposed to show up, and we want to give those who've experienced sexual trauma the freedom to show up however they need to show up, and that might change from day to day, month to month or moment to moment, and so sometimes we don't even have the words that they have, that they share with us, that we accept and receive as human beings and the humanity that we need to always have. And we're talking about these things.

Kalimah Johnson:Healing is possible. Healing is work, healing is your own work, and it may not look the same as the girl sitting next to you or the guy sitting above you or beside you or behind you, but at the end of the day, being able to call it, name it and being able to say I'm here because I don't know where to go from here, and we'll say well, we don't know where you're going either, but we're going with you. And sometimes lowering the isolation that Black people feel and experience as a result of sexual assault is way more important than food, clothing and shelter, because I promise you all the programs that have these food, clothing and shelter. We partner with them, but at the end of the day it's a revolving door and they keep coming back because they never had a chance to really unpack that other trauma.

Donna Givens Davidson:So you're really getting at the root causes not the symptoms.

Kalimah Johnson:Absolutely.

Donna Givens Davidson:Which could be that I'm homeless, or it could be that I am unable to hold down a job, but the root cause may be something, a story that hasn't been told a story that hasn't been told and so creating space for my story, and my story is my story, it's not your story, it's not anybody else's, and we are all walking around with these stories. So when somebody comes to you and you mentioned earlier I don't know if you mentioned when we started recording that most of the people who come to the Sasha Center were referred by men, or many of the people were referred by men- A lot of men can take credit for sure that they have told people about the Sasha Center and have shared with women.

Kalimah Johnson:But now some women come on their own. Don't get me wrong, they will show up. And sometimes women who come to our support groups don't come happy, they don't come ready, they just come.

Donna Givens Davidson:I was assuming that was kind of my question.

Kalimah Johnson:Yeah.

Donna Givens Davidson:That you have somebody who may not have figured out what their healing pathway is. Right, right, right, because I'm not healed. I'm not even in the process of healing. I'm still feeling very broken. Yes, and they come to your support group. What is the process by which you see people moving from whatever broken state they're in to one where they are more healed?

Kalimah Johnson:When they tell us. When they tell us.

Donna Givens Davidson:Right, but I mean what is happening that helps them in the healing journey.

Kalimah Johnson:I don't know. I can't answer that question, because that's a question that a survivor would be able to answer better than me is, when people come to us, they come to us sometimes whole and healed, under the gaze, and so they will present and they will come in the room with it all together. One of the things that I will say that your question is making me think about is, sometimes you, when someone is healed, when they can tell their story and when they can hear one, and they can do it both at the same time, that looks like healing to us, but we don't mark it, we don't say, hey, you're healed now, because it's a journey.

Donna Givens Davidson:Yeah, but I mean as a social worker, as a licensed professional, I mean you have an understanding of what are the ingredients for that journey, what are the things that need to happen in order for that journey to be successful? Although it's individual, the Sasha Center exists because you have some thoughts around.

Kalimah Johnson:So you want me to put on my social work? Hat I?

Donna Givens Davidson:want to. No, I'm just thinking that I love what you're saying. You know, let me say this my first job, I worked in HIV AIDS in 19,. Well, my first professional job, 1985. And I was working with men who were recovering, who had been diagnosed with HIV AIDS in 1985, that sentence. And so I don't know how I ended up being the support group facilitator, but I was 22 years old. Which agency it was Community Health Awareness Group, which is an agency that was started by the Detroit Health Department.

Donna Givens Davidson:It was a CHAG and it was a quasi-public. There was not even a board of directors when I started working there, Wow, it was very much the Detroit Health Department. Would you know help?

Kalimah Johnson:facilitate. Oh, don't let me start name dropping Darlene Franklin, Hank Milbourne, all those folks. Hank Milbourne, all those folks.

Donna Givens Davidson:But this is Hank Milbourne, but we're talking about Linda Campbell. Yes, george Gaines, cornelius Wilson.

Donna Givens Davidson:Yes of course, cornelius, yes, a whole group of people who were there, and so I'm facilitating the support group and what I found is that people just wanted an opportunity to tell their stories and they told their stories and somehow we had an interesting conversation and I learned a whole lot from them. I learned more from the people in the group than they learned from me. But what I found is the telling of the story, the sharing of that and the honoring of that made people feel seen and heard and valued in ways.

Donna Givens Davidson:And so I started hearing from people at that time I'm living better than I've ever lived, now that I'm about to die. And I heard that over and over and over again and that kind of propelled me into this work because I was like, wow, what if we intervened and provided interventions while people were alive and not dying, While they were young, before all of these things happened? So that's why we have youth programs. It's been very important to me personally to intervene at a place and time when it makes sense and when a person can benefit from that. But from my experience it was really the forming of a community and the sense of belonging and the sense of being valued. That was what allowed people to heal inside of that space, Even though in this instance they were dying.

Donna Givens Davidson:But then I came to Warren Conner in 1993. We started the Partnership for Economic Independence and we had a dinner club we didn't call it a support group, but it was the same thing and people would just come and talk about their stories and their journeys. I talked about favorite topic was beating kids, the best way to beat kids, get them to behave. And you know I wanted to say, wow, yeah, it was. It was interesting. But there was always somebody there who would tell people there's other ways to raise your kids, and then they self-correct. But people change their lives just by being in a place where they were cared about and we didn't do any real preaching about get a job or you know.

Kalimah Johnson:Yeah, we don't do that. So exactly when you create a space for people to be able to tell their stories and to help them practice listening to other people's stories and lowering the sense of isolation because it can be very isolating, especially in Black families, because we are sometimes taught that we need to take these traumas to our graves so that their family can stay intact. I don't know how many times we've had experiencers share with us that they were forced to break bread with people who have caused them harm from when they were very young, even through adulthood, is that at the Sasha Center, we really work hard at allowing people to be together, to identify, to say, hey, that story sounds familiar, what did you do? And they learn from each other. Our facilitators are really good at creating opportunities for people to really question their decisions that they're making from day to day, about what's important to them, about what makes them feel better, about what was it in life that you really wanted to be or do or become? Know that it's never too late, and so at the Sasha Center, too, you know like we engage, which most mainstream programs have not learned to do this, but they are imitating us a lot lately and borrowing a lot from us lately, like our Black Women's Triangulation of Rape model, which got tweeted over 10,000 times, is we already have what we need to heal and we work hard in our sessions because we don't do individual therapy or counseling.

Kalimah Johnson:We believe that we heal as a community together, all of us together, even as I think about Love with Accountability, which is a text that came out a few years ago, edited by Aisha Shahida Simmons, where people and community of color people, members of community of color talked about how they forgave and how they worked through the pain of the people who caused them harm, and it's called Love with Accountability. Please make sure you pick that up. My story is in there. There are two other stories in there from Detroiters who have been doing this work, and I also belong, speaking of which, to the Black Sage Collective. We are partnering and actually they're vendoring for us. They're our premier vendor, if you will, at our annual Friends and Family Day. This is our fifth year having it. It's on Saturday, on the 23rd, but one of the things I want to say is that when we are in community as a group of Black people, sexual assault, rape and talking about it is tough, but it doesn't have to be tough. The entire time. We use humor, irony, satire literature.

Donna Givens Davidson:That was my experience, even when we were doing HVACs. I laughed.

Kalimah Johnson:I never laughed so hard because you know, people are just humorous.

Donna Givens Davidson:And humor can be healing. Of course you're not always laughing, but yes, I love the fact that you mentioned that it's not all sob stories.

Kalimah Johnson:Of course there are the stories that bring tears.

Donna Givens Davidson:But in a lot of instances the bonding, and I think that's cultural too, Like we bond over humor, don't we?

Kalimah Johnson:Donna, let me tell you something. Do you know that? We don't even ask participants who come to group to tell us what happened to them? Right, because it ain't none of our damn business? Exactly, and that's what they're going to say, right? And so what we're really focusing on is providing people with tools that they might need to integrate the experience, to live a better life, to make better decisions, to do all these things. We don't even ask for disclosures. They will come when they're ready or not. And so this typical way that therapeutic work is done and textbook-like.

Kalimah Johnson:I remember when they first started finding out how we actually do the work, our funders. They wanted to know. Well, tell me this how come, when they have the first group on the first day, how are you taking an evaluation at the end, when that person may or may not be there? We take the evaluation of those who are there, and so I think, for a long time, we're counting the wrong thing, orlando, we're counting the wrong things. Count that she clicked, count that she said she was coming, count that she came. But if you're counting how many times we don't do that. And then we have virtual sessions, and sometimes, on our virtual sessions, I promise you sisters, be in there and be like I got to. I got to break this down, but I got my headphones on and I'm right here and we don't say stop, you're not ready for group, you are ready because you're here.

Donna Givens Davidson:I absolutely love everything that you're saying.

Kalimah Johnson:And I'm glad I'm saying it, because people really don't know.

Donna Givens Davidson:They make assumptions about what we do at the Sasha Center. You know it taps into what I think is the wholeness of people and this belief that people are, you know, have gifts all of their own, and it's not that kind of top-down idea of me, the expert, and you, the you know the receiver of my expertise.

Donna Givens Davidson:I'm the smart one and you're not. No, and that hierarchy is you know. And then I think about you know. There was a young lady who wrote a book I don't remember the name of the book where she talked about the history of therapy and psychology in the United States and the way that it was actually used in so many ways to oppress oppressed people and to put them into, categorize them. I think traditional therapies have a way of putting people into boxes.

Kalimah Johnson:Listen. When I was a kid, in the church I would ask my mama, why don't people catch it during the announcements? Okay, when I got to college, I said I'm here with a GED, a good enough diploma, and so systems have never me and systems have never gelled Like. I've never been able to fit in a box, and so why create a Sasha Center where it's a box? It doesn't make sense to make it a box. What makes better sense is that we come and co-create together and we have experiencers who have participated in group, who have a heart for the work, who are open to our training to learn more about our culture and how we actually operate, who become facilitators that make the same amount of money as my PhDs they do.

Donna Givens Davidson:I'm smiling and laughing because I don't really. We don't really use degrees to determine who does what, or even age, right, Right, it is because we have this way of sorting people out. So I mean, I just can't even tell you how much I'm loving this. Can you talk about the Black Women's Triangulation?

Kalimah Johnson:A rape model. A rape model, a rape model, yeah, I can, um. I created it um back in 2016. It took until 2018 to get the full copyright, um, and then, when the surviving r kelly series uh came out, I was at dream hampton's house, um, and she didn't want to watch it alone, so she had a few of us there in space, you know it's so.

Orlando Bailey:I don't mean to interrupt. You were you there, I just think this conversation is so, so sacred, um, but one of the questions I was gonna ask you no, I was not at dream's house is number one. You know, dream like, do you know dream because the cadence with what y'all?

Orlando Bailey:y'all have a similar cadence and how you expose your value and your work, right, I'm also we are co-conspirators, yeah, and I'm also hearing the kind of the protectiveness of your work and your intellectual property and your models that Dream also has for her work, work and much like the work that dream does, um using, you know, storytelling is a through line to get to a certain place we're both rooted in hip-hop from, and you're both rooted in hip-hop and she has a complicated relationship with hip-hop right now.

Orlando Bailey:I wanted to ask you about your relationship with hip hop. But you saying I want you to finish this. But you saying you was at Dream's house and y'all are friends. I'm like, oh, it makes sense I was legit.

Kalimah Johnson:I would say we're more co-conspirators than I would say friends, but I adore her.

Donna Givens Davidson:I need to connect with Dream off camera. I mean, you know, afterwards I'm going to talk to you about that, but the triangulation.

Kalimah Johnson:No one would know about that model if it wasn't for Dream Hampton. I literally had been working on it for two years, from 2016 to 2018. I think it was 2019 when Surviving R Kelly finally came out. If you saw the series, I told her I did not want to be a talking head in the movie and she was fine with that. But she came and got all that footage from when I actually coordinated with one other person, a younger person who really I couldn't have done it without, nicole Denson, the protest at the last R Kelly concert here. But it wasn't just the last protest of his concert here. We actually got the city of Detroit, the council members, mary Sheffield and all of them signed off and say he could never perform here again. So we were doing some real serious political work around it, but also some activation and some visibility work around why we need to start holding people accountable for the things that they've done.

Kalimah Johnson:And Dream. What happened was we were at her house and that was the first and only time I've ever been in her house and she had asked for me to come and watch the premiere and it was me and a few other people. Here's another name, invincible was there and Invincible okay. So Dream looked at me and said, right, as everything was coming up and she was on Twitter doing something. A lot of things was happening at the time that the premiere was happening. And she looked at me and she says is the model ready? I was like, yeah, it's ready. She was like ready, ready. I said ready, ready, copywriting and everything ready. She was like tweet it. And I had my phone in my hand and I don't know how to tweet. I didn't know how to tweet, but we had a Twitter page. All of that was set up. I knew enough about it like that. But I'm fumbling. Invincible was like you need me to help you. I said, please, and I handed my phone to Invincible and Invincible tweeted it.

Kalimah Johnson:And then the next thing, you know, it just got for us to have a black feminist lens, a literary lens, a political lens, a systematic lens, social work lens, of explaining why it's so difficult for black women to report a rape or to get help once they have reported a rape. And we went deep, all the way to what Henrietta Lacks went through. We talked about Sarah Bartman, we talked about the Jezebel, we talked about the Mammy image and the stereotypes. We talked about Moya Bailey's work with Misogynoir. We talked about, you know, audre Lorde's work and the Cahimbe River Project, and all of those things were fed into this model to help people see, this is why we don't say sugar, honey, iced tea.

Kalimah Johnson:This is why, this is why we're angry, this is why we fight back, this is why we push, this is why we're resting, this is why we are organizing, this is why Because, if I tell you I've been sexually assaulted and you're a part of a system that's full of power and you write on a piece of paper that this heifer is lying, then we have to sound the alarm.

Kalimah Johnson:And so the model is really a sounding of an alarm to say, hey, where are you in this model? Do you see yourself the objectification of girls' bodies, all of that, and also there's some respectability politics involved in the conversations we need to have amongst ourselves as we're healing. Right, I think sex workers need to be unionized. It's going to happen. At least they could be safe, right, you know? And but a lot of people, when they see Sasha Center, kalima Johnson LMSW working on a PhD, getting this funding from the federal government, that I'm falling in line with mainstream programs. Mainstream programs need us, like people in hell need ice water, and I'm talking about the blue parts of hell. I ain't even talking about the cool burning orange and red.

Orlando Bailey:You know, I think we could continue for forever. It has been such a joy and privilege to just witness witness your spirit, witness your work, and for you to have this opportunity and sounding board to tell the story of your work, the story of Sasha Center and your own personal story.

Kalimah Johnson:We gotta get back to hip hop. I hope that we hear more of it Next time we will come back.

Orlando Bailey:You gotta come back and we gotta talk about hip hop and your relationship to it and your love for it.

Orlando Bailey:Kalima Johnson, everybody from the Sasha Center. If you have topics that you want discussed on Authentically Detroit, you can hit us up on our socials at Authentically Detroit, on Instagram, x and Facebook, and you can email us at authenticallydetroit at gmailcom. All right, it's time for shout outs. I got a really quick shout out. I want to shout out our listener, erica, who was listening to us so intently last week and she realized I misspoke a stat when we were talking about the election, the primary election of 2025 and the turnout Just the position to the turnout in 2021. So I want to correct it. This is authentically detroit, so sometimes we say stuff and we misspeak. I know the numbers. I misspoke the numbers and so, uh, the turnout numbers from the 2021 um election uh, from the city for the primary was at 14.28 right, which was less than the turnout in the 2025 primary election. That sat at about 17%.

Donna Givens Davidson:First of all, shout out to Orlando for your commentary after the election. I'm so proud watching you I feel like a proud mama. I just have to tell you you are a proud mama, I am right, but you know, it was just amazing. So you know you really bring a different level of whatever to it. You bring some context, you bring some facts. You do a great job and they need to keep you in that role.

Kalimah Johnson:You know he— Ditto Listen. That night, every time I heard his voice I would rush back in the room. I'm like, okay, he's talking, okay, pay attention.

Donna Givens Davidson:You know because he speaks our truth. And it's not often that you have somebody who speaks your truth, who's a talking head on those shows. So thank you for that, orlando. But I do want to shout out the ECN team. Yeah, we had two. Well, I was on my vacation last week. We had the completion ceremony, or ice cream social, for our 39 youth workers this summer and they worked in internships and various programs. They presented what they learned. I was so proud at the impact that this program had on these young minds.

Donna Givens Davidson:And then, a few hours later, we had a transportation fair where we were educating people about various transportation resources, really trying to get people into non-motorized transit, we raffled off buses. I mean buses. We raffled off bikes and we shared information about our electric vehicle car share. It was just a beautiful event. Over 100 people came to that and to make all that happen in one day, with our team coming together, it was beautiful. I was not here for all of it, but I was proud of all of it, so hats off to you, ecn.

Orlando Bailey:Clem, you have any shout outs?

Kalimah Johnson:Yes, I want to shout out you, orlando and Donna, thank you so much. Thank you so much. I also would like to give a shout out to Catalyst Media and I'd like to give a shout out to Sasha Center, all of our facilitators, our board of directors and our participants. It is always a joy to serve. It is always a joy to serve with that Detroit geography. It is always a good thing to connect and to be involved, and I just want to let folks know if they're interested in joining us virtually or in person. They can go to the website and check us out. But I am just wwwsashacenterorg and we're we're on instagram at sasha center and we are on facebook at sasha center as well. Follow us all those places and my male facilitators, dr spencer murray and omari barksdale. Um, and to the poetry community, because without the poetry and hip-hop community there would not be a sasha center. So I'm just really glad and proud that I have that kind of a village with me so thank you for letting me shout them out.

Orlando Bailey:Amazing, amazing. We had to have you back. You have to come back, so we're going to figure that out after we get off the air, but we thank you all so much for listening and until next time. Love on your neighbor. Outro Music Bye.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.