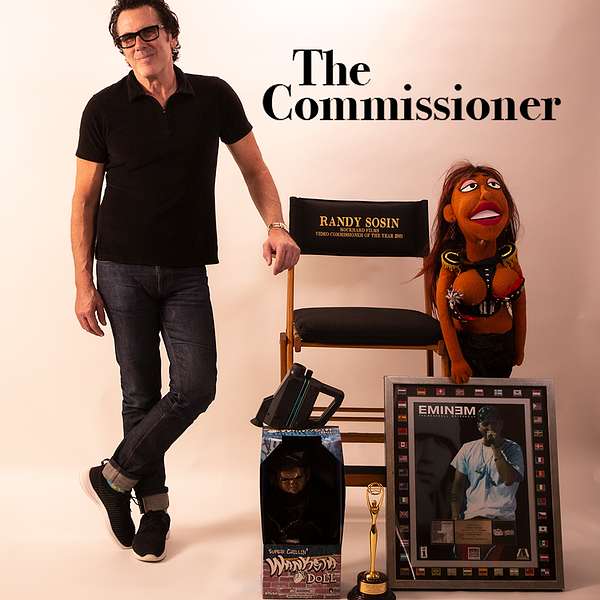

The Commissioner

The Commissioner

Commissioning 101

This is a Music Video Podcast - or should I say a Podcast about Music Video. This is a slight detour on our trip through my past. It's called The Commissioner for a reason. The job of Music Video Commissioning is a unique, exciting and somewhat complicated job. I do my best to describe what I did, how I did it and my philosophies behind decisions. I hope you enjoy learning about the process. Next week I will be back to my regular programming with a full episode on Eminem "Lose Yourself."

Hello and welcome to the commissioner. My name is Randy son. This is episode six, commissioning 1 0 1. So what is a music video commissioner? If I had to break it down, it's kind of a ven diagram of where a creative movie producer, who would hire the director and the production team. Um, a movie studio, because as a commissioner, you basically are financing your own movie or video as it were, um, a brand manager where your brand is the artist, and you need to make sure you're making the right product for that artist and kind of a zeitgeist predictor, if you will, where you're knowing what is out there in the culture of music, depending on the genre and what other artists are doing and how you can be unique and, um, thoughtful for the artists, but also make something that's very creative that captures the attention of, of the population to back in the day, when I was making videos, it was a very closed distribution system. So they were pivotal to selling, selling music, which is much different than it is today, where you can stream anything you want and videos are, are judged on views. But I think most of the time people are just listening to them. Not that they don't watch them, you know, cuz I do think people do watch videos. I just don't think they watch'em a thousand times or a million times. I think they watch it a couple times and then you listen to the video as the audio. So that's kind of where that ven diagram kind of, that you're in the middle of that kind of four intersectional, really important pieces. Um, and that's, that is a music video commissioner. It's kind of a, it can be somewhat enigmatic because I don't know that it's something you can fill out on a school, um, wishlist for, with a counselor. I don't know that you go to school for that, you know, kinda like being a manager for an artist. I don't think you go to school for that either, but it's an incredible job and something that I loved doing for many years. Okay. So that's what a music video commissioner kind of is from 30,000 feet. But what, what does a music video commissioner do? Um, you basically are in charge of making the music video for the artist at the label. So where do you start? Right. So the um, where you start is the, uh, marketing a and R promotion department pick a song, right? They've decided whatever the artist is, they've made a record and they're picking a song and depending on what it is, it's can be the first single from a new release. It can be the second single from a big hit record. It can be the second single from a record, from a big artist that had a stiff first single there's a, there are a myriad of things that are, you know, determined on that, you know, uh, song that gets picked. But the video commissioner doesn't pick the song you're given a song. Um, and then you listen to that song, right? And you're start to think, you know, about what the artist has done in the past or maybe this is their first video where they fit into the marketplace. Um, what, what would be good for them? What their visual things are, you meet with the artist and the manager usually and talk to them about what their thoughts are. And, um, you're given a budget which can range, you know, back in the day, the lower end videos were 75 to a hundred thousand. And you know, at the high end it was a million plus for, you know, it wasn't uncommon for bigger artists to spend a million dollars on a video. I'm not sure what budgets are today. Uh, but you know, I'm guessing people do spend a lot of money on them. If you wanna get good people and quality people to do really good film work, you need to pay them as they sh they should get paid. So, um, once you have a kind of an idea of what the artist wants to do and you should come to that meeting, I usually did anyways, would come to the meeting with a kind of an idea of what you're thinking and where they would fit in at that point to the, to the zeitgeist, if you will, of the music thing, depending on the genre, be it hip hop or rock or pop, um, you know, each artist has their own fan base and, and you obviously want to please that fan base, but you're always looking to expand the fan base without being alienating to the fan base. Um, you will, you come to the, uh, you know, the meeting with ideas and then you leave there with a basic understanding of kind of what it is you are setting out to do with this music video. From there, you call production companies who represent directors and talk to the either executive producer or the, uh, the rep for the director and kind of discuss, uh, the directors that you're interested in and their availability, um, and the interest, you know, bigger artists pull in. Obviously there's a lot of young music video directors that want to do bigger artists because it's a great opportunity for them in their career, um, which sometimes, you know, would happen. Um, there's also back in the day, there was a lot of, um, you know, competition for the bigger directors and they were very particular and, you know, would pass on a lot of, um, a lot of the times I would call to see if Alor SIGA, Mondi was interested or a Sophie Mueller or David Cher or a spike Jones. You know, those kind of are those kind of directors would, would be very picky. Um, they tend to have relationships with artists that they like to work with. Um, especially as they got bigger and started to do more commercials and feature films, um, they, you know, pretty much would turn down a lot of video work, um, do a to availability B to lack of interest in working with the artists. And it wasn't necessarily mean spirited. It was just, you know, creatively, they didn't think they could bring something to the party. Um, and so from there, once you have a list of directors that you know, are available, um, because you're obviously looking at scheduling this shoot, right? And there's a, you know, the production, a promotion and marketing team is like, here's your song, here's when we're releasing it. Here's when you have to have the video done. The whole process usually takes about six to 10 weeks. You know, the longer, the better, obviously from, from a film production standpoint, because, you know, putting everything together and budgeting and availability, depending on what the thought the process is, or the idea is, and locations and et cetera. And then also based on when the artist is available, you know, bigger artists have tours that they're on, especially if it's a second single they're already touring. So sometimes you have to go to location, which you have to fit into your budget and all these, you know, kind of variables that exist for the pro project to go forward. So you're, you know, you're, you, you know, talk to the production companies, get a list of directors, um, go back to the managers and, and let'em know her know, let'em know that, you know, here's the list, here's what we're getting. We're gonna get treatments in give, and you give the production company a date, you know, by this date, Um, a treatment is usually one page to three pages. Some people use image, you know, visuals, um, just a quick breakdown synopsis summary of what they wanna do. It's, you know, pie in the sky. Um, I would always have this really fun challenge of, you know, uh, challenging directors to, you know, give me a video treatment in one sentence. And, and, you know, I think the spike Jones had those. I don't know that he did them in one sentence, but if you've ever seen the dinosaur junior video that he did, you know, it's like Manhattan is a par five or, uh, that wax video that he did with, you know, man on fire running to catch a bus, you know, like it was those kind of things are just, you know, or the BC boy sabotage video, you know, a Quinton Martin cop show from the seventies intro, you know, so those were always like, oh, I get it. I totally know what that could be. And then obviously the brilliance of the director would come through, hopefully in, in that thing. But most directors can't do that. And, and I get it. It's not easy. That is not an easy challenge. And a lot of times, as a director, you wanna explain yourself, so they write summaries. It's, you know, 1, 2, 3 paragraphs five paragraphs, the longer it is the, the harder it is to digest. So most production companies go through that process and, you know, will, will edit it to the point where it's, it's they know they're sending you something that's they feel good about that they can do for the budget and you know, that they can, you know, that that's readable. So that me as the commissioner and the artist and the manager look at it and it hopefully jumps off the page and they're excited about it, um, that becomes, you know, so eventually you get down to that, oh, this is a great idea. Um, you know, you can do a conference. Sometimes artists want to talk to the directors. They sometimes they know the director and that becomes an easier thing. Sometimes most of the time they don't. So they would wanna do a quick call just to kind of have them explain it. They have some questions, you know, um, artists are very particular about their brand and what they wanna do, directors are very particular about their idea and what they wanna do. So the commissioner's job is to delicately, make sure that both are served properly so that you can have the artists with their integrity of their brand intact and the director to give you the best possible video. Um, and that is, that is a little delicate thing that you learn as you do the job. Um, I came from before I was a commissioner, I was actually at a production company representing director. So I, you know, obviously had that side of me, but would work with a lot of artists and was able to, um, you know, understand and get my directors to, to, I wouldn't say Ben, but, you know, appreciate the artist's point of view because it's very important. And ultimately it's their vision. It's the director who brings it to life and puts that. But the artist has to be in front of the camera, so becomes quote unquote, their video. Um, so from once you have a, a treatment and then they give you a budget, as far as budgets go, I was always very open about my budgets. I know a lot of people don't do that and I there's, I wouldn't say there's a right or wrong way to do it. It becomes you as a person. If I was given$150,000 to make a video, I would usually go to the production company with probably 125 or 130, depending on the artist. Um, knowing that I had cost built in some artists have their own stylist. When you deal with a lot of hip hop artists, there's a lot of entourage that has to be covered in the cost of the budget. And so if you're flying in a number of people, you know, um, a solo artist or a band you're talking about, you know, four to six people, maybe with the manager seven or eight with a tour manager, you know, hip hop artists can be 10, 12, 15 people. Um, and, and those people have to be flown in and put up at a hotel and there has to be ground transportation. There's usually meals that have to be accounted for. Um, so, you know, you wanna make sure that you're giving yourself enough money in your budget, that you handle that as a commissioner, because it is your responsibility to make sure you bring the video in on budget. And so, um, you, you know, I would, but I'd like to give the production company as much of the budget as possible, because I always felt that a music video people work their asses often need to get paid and B the more money you spend, if you spend it properly and really put it on the camera, you, you know, get you get what you pay for. You really do. You can really push things in and you know, it is your job as a commissioner to know what things cost. So when you look at a budget, when they finally do turn in a budget, you can go, it's usually a line item budget. That's done very close to an a I C P, which is the commercial production budget. So it's, you know, broken down by lines and broken down by departments and broken down by cost of day rates and days and equipment. And, you know, PO in video, you have to, you know, do posts. When I first started doing video, most of it was shot on film. Um, so part of the budget was, you know, after the, you know, you shot everything on film, you had to transfer it, or do what's known as a Teleny to get it to a digital realm, to be able to edit on, you know, Avids or, you know, at one point final cut was there. It's just kind of when I was doing it was before Adobe, but either way, it's, it's a, it's a non-linear digital, um, realm that all the film had to be transferred. And in, and in that transfer, you could give it a look because you had colorists that would take the film and process, you know, give it a real interesting look. Um, uh, used there, you know, in the beginning, beginning when they did that, it wasn't that we used to edit on, you know, Sony and three quarter inch tapes, and you would have to visual, you know, physically put in the tapes and it would have to read the code. And so, but once avid came in, it became a much more, um, fluid process, but either way, you still had to do it on film and then transfer it to digital. Now, pretty much everyone shoots on digital and you can even set cameras looks in cameras, although I'm not sure why you would do that, but you could, you can do that if you wanted to. Um, so it's a little bit easier process, but there's still a Teleny, I'm sure you still wanna set your look and still get that, you know, colorize the, the, the raw footage to make it look like your vision, whatever that director and the DP are. All right. So now you've got the treatment, you got the budget, it works, the artist and management is signed off. You have your shoot day. Um, you start to work with the production company on who they're hiring, who the director wants to hire for the director of photography and for the production designer, and you know, where the location is to make sure that it's doable and, and, and any sort of special request that you might have for the artists where they need to have, you know, if you're gonna be on a, a, a remote location or something, making sure that there's a star wagon so that they can get ready and that there's air conditioning, because if it's hot out there, they're gonna need to not look sweaty and disgusting in front of the camera. So, um, so you get all that sorted. You, you know, I, I was always a commissioner who, I don't know. I, I, I knew people that I liked and that would work, and I wanted to at least sign off on the director of photography and production designer. Um, but I would never stop somebody. I never had a list of people I didn't work with. Um, I was never spiteful like that. I just sometimes know that people take longer. And sometimes that didn't work for some artists there. I've had a couple of jobs, which when I'll get into in specific videos where we did have to, you know, get rid of certain people on the crew for personality reasons and whatnot. So, you know, that becomes an issue. But for the most part, I pretty much let directors hire who they wanted to hire. Um, or at least I think I did. I'm guessing once these come out, they'll let me know that I was the ogre, but I don't feel like I was. So that's at least my experience of it. Um, there's not a massive pre-pro in music video because of time and money. Um, usually usually I'll just go through with the executive producer and the director on a quick call, kind of talking about the day, um, you know, and then get to the shoot. And when I would get to the shoot, I would, you know, immediately go into the production office, talk to the line producer who is responsible for the whole shoot, as far as production goes. And then, you know, get a call sheet at a shooting schedule and try and sit with the first ad to figure out the day and see how realistic it is and see what the plans are like any, like anything else. Everyone has their style. My style for music video has always been, you know, while you're setting up to do something great, try and shoot a performance of the artist, because at the end of the day, that pretty much can always just be the it's like fail safe. Right? You get, um, you get a good performance in with the artist performing the song to the camera, and you pretty much have the basis of a music video. Not every music video is like that. And you can't do that for every music video and some guys, and some girls don't wanna do that. And I respect that, um, some per some videos have no performance at all. So, you know, there's, you, that's not something you can do for that particular video, but for the bulk of the videos, it's usually a good way to get started. And it gets the artist feeling better about themselves when they're performing the song. So, um, that's, you know, that's the bulk of what you're doing on the shoot. And then, you know, you have your, excuse me, um, your, you know, your, your shoot when you're doing most of the time, it was a two day shoot. Um, sometimes, you know, like I said, the lower budgets when you're at 75, I know it sounds like ridiculous, but when you really have a good crew with a high end DP, who's got a real grip and a gaff, a whole electric team that has, you know, theirs and utilities and then a production designer and a costume designer. And you have catering and you have location fees and you have production. You know, people get paid rates as they should. I was always a firm believer that you work a day, you get paid. So, you know, believe it or not, filmmaking is expensive. Um, and rightly so, because you're paying for someone's services and they're not, there's no per, uh, like ongoing, uh, residual for a music video. The only people that get paid on a residual are the artist and the label. So when you're a director and you put together a crew and everyone shows up for that day of work or days of work, they get paid their day rate, and then they're done, and then that's it, they don't, and it could, you know, it could in today's world, they could have a billion views on YouTube. I don't know of any organization that's collecting fees for the crew. So, um, I always, you know, I, I would always have the discussion with people it's so expensive it's and I'm like, man, it's not really, you're actually getting a really great deal for your, for your dollar, because you have these high end, amazingly talented crew people who are doing really, really great work, um, putting together this, you know, magic, you know, and, and unlike feature films, most of the time, there's no dialogue, you know, you're this, the playback is what's known as MOS, which is without sound. So you're not recording sound, you're doing it to a track. So there's been an audio package made. And if it's a rock band or something, you know, they're, they're playing back to the song that's played there's time code. And so, you know, that's, you know, having produced a couple movies myself, like once the, once you roll sound, there has to be, you know, complete quiet and blah, blah, blah. So a lot of times you're not experiencing that on a music video set, which make, does make it for an easier, um, environment. And you can shoot in places where you probably couldn't shoot a movie because there's noise, but you don't have to really record it. Now, I'm not saying that you don't have audio, cuz there are times when you do have audio and there is dialogue and you do shoot a scene with, you know, the artist talking or there's an acting scene with somebody. And so you know that in those situations you do need to record sound, but for the bulk of them, there's not a lot of audio recorded. Um, so you get your shoot in. Usually I try, you know, I don't have a lot of money that I've left over. So you try not to go into overtime. Videos, tend to have overtime. That's just the way it is. Um, I think production companies, you know, a lot of them may be outta business because of that. They do invest in the art, the director. Sometimes they wanna do things that make it go over. If it was the art, if it was my artist's fault for going overtime, I would pay for the overtime. If it was just bad production, I didn't pay for the overtime. Um, it's just not something that I felt was my responsibility. Um, as bad as I felt, I just felt like it was, you know, to be honest, not my, not my fault and I didn't have the money to do it. Um, I would always, if, if it was the artist's fault or there were some issues and I I'll go into it on specific videos, we had some colossal things we got, I got on a D 12 video, we got shut down by the New York police department. So we literally had a full day that we had to make up, which was, you know, upwards of$250,000, um, in New York. But we'll get into that. That was the D 12 fight music video. Um, but we got it done and ultimately, you know, it got, it got sorted. Um, so you do your shoot, you know, you rap, everyone's excited. And then you go into, um, the edit Where, you know, the first thing you do, like I said, back in the day was a Tai I'm guessing today. They still have Tallis where you sit with a colorist on a very incredible board and you can, you know, really manipulate the colors and, you know, what's is crushing the blacks and bring things out to make sure that the, uh, picture is as, uh, spectacular as possible. Um, you know, most of the time on video shoots, you're you? Well, certainly back when we were doing, it was 35 millimeter with, you know, you know, cinema lenses. And so you had this really crisp picture. Um, you know, there, there was a movement of 16 millimeter back in the late eighties, early nineties that gave it that gave it its own look, its own like kind of dirty Sandy, you know, over modulated kind of thing where, you know, like that, but that became a thing. And that was cool. But most of the time when I was doing videos, we were shooting pretty clean 35 millimeter setting the look. And then once you get all that footage onto digital, it would go to the editor, they would edit the video. The director sits, you know, would, you know, sit with the editor, whatever and get you, get you a, what's known as a rough cut. Um, I would always look at the rough cut and I obviously had my notes and things that I liked things that I didn't like, things that I wanted to change, um, stuff that I didn't want in the video, but I would always send that first rough cut for me to the artist because I wanted to get back to the director and the production company with full notes. I know a lot of people don't do that. I know a lot of people make their edits and then send it to the artist unless of the video is in such bad shape that I couldn't even send it to the artist which can happen at times. Sometimes there are directors who have really good instincts on making a thing, but they're not necessarily great editors and they didn't have a good editor or whatever it was. Um, sometimes I would've to go sit in there for a night and just get it to a point where I'm like, okay, now I can at least send it. Cuz if you send something that's so bad to the artist they'll um, rightfully so panic and think that their video's unwatchable. So I never wanted to send them something like that. But most of the time I would get a pretty good cut, pretty good. I first rough cut something that I would, you know, have changes that I wanted to make on it. But I would send that along to the artist and the manager and talk to them about it. Um, they would ask me my thoughts. I would usually give them my thoughts. They had their thoughts. I would, you know, some things, I like some things sometimes I had to talk artists out of things or say, no, no, no, you look great there you're wrong. And you know, but you know, ultimately it's their video. So I would do my best to fight for what I believed in. But you know, in the end you do give into the artists wishes as long as it doesn't, you know, in your mind hurt the artist. You're never, in my opinion, giving'em enough rope to hang themselves. That's not something you wanna do. And most artists don't wanna do that. I'm, I've found that the artists I work with tend to trust your sensibilities and, and they want to know what you think. And a lot of times they don't have a lot of people around them that will give them straight honesty. So as a video commissioner, I always felt like I wanted to give them the true, um, my true thoughts. Um, so then you get it to a point where it's ready to go. Um, there is a, a, a mastering process or a final process where, you know, you go in and finish it. You can do some final tweaks. There's some use some, you know, beauty work that can be done in the, in the final edit. And then, um, for me that, you know, we used to deliver God, we used to deliver on like, you know, one inch or D two digital things. And, uh, like the, it was a, a digital master is what we had. And so, um, from there a and at the same time, once I had a rough cut that the artist was okay with and the, I was okay with, uh, we would send it off to the promotion, the video promotion department, who, depending on the artist would send that to MTV, cuz that was the holy grail of music video was getting onto MTV. Um, nowadays you make a video and you put it on YouTube and anyone can see it whenever they want back in the day when I used to work, do videos, I know that sounds so grandpa like, but, and I don't mean it in that way, but it really was a different kind of ecosystem where you, you know, the bigger artists would make a video and of course it would go onto MTV because that helped the, the channel get viewers. But there was a lot of young artists and, and up and coming people that didn't get onto MTV, but you would try, you know, you'd make the best video and hope that they would put it. If they didn't put it into big rotation, they would at least put it into some sort of specialized programming or something. But either way, MTV had a whole process where you couldn't have any label. So there was always a blurring process cuz it was advertising. They didn't want people to get free advertising in the videos. So a lot of times, certainly in hip hop videos, you would have Nike logos or Puma logos or any, you know, cargo, kale or whatever, any sort of, you know, any logo of any brand had to be blurred out. So sometimes we blur them. Sometimes we would just paint it O with the same color, whatever it was, that was a whole process. And then there was also, um, a standards, uh, you know, kind of pass that MTV would do where they would go through and tell you what, what was okay and what was not okay. Um, there was, you know, obviously there were various like no smoking, no, um, um, uh, you know, no drug use, no sex, no nudity. Um, but sometimes they would just have things where like, you know, when we did the M and M stand video, um, they did not want Dito in the back of the, you can't have people held against their will. So even though in the original version of the video, DDO was in the trunk at the end, when he's driving in, we had to cut that all out for standards for MTV. Um, and I'll get into a lot of those specifically when I talk about the specific videos, but, but I would always, I would always try to send the video in its purest form, knowing that I would have, if there, you know, if there were a hundred things wrong, I was hoping they didn't see all of them and that I would make my 40 or 50 changes and try and get it as pure as possible. Cuz while I understood some of them like the logos and others, sometimes they just got, you know, picky nitpicky and it became a way for them not to program videos. And there was always a push and pull between the label and the channel. But ultimately you deliver your final video and you know, hopefully it goes on MTV. And um, I remember, you know, there were some people who used to say that what's a good video, a good video is a video that gets played on MTV. I didn't always have that thing. I always thought video was an art form and really liked it. But I loved when my video got played on MTV because it was a way for your work to be seen by millions of people all at the same time. Um, you kind of put yourself into the, the discussion of pop culture or, you know, music culture, and you hopefully are pushing the envelope to make people make better videos. So I always, you know, strive for that as a commissioner was always, um, really proud of the videos most of the time that I did and that that got on MTV and when they didn't, I would try and, you know, send them around there. Weren't a lot of outlets. You know, YouTube became a much diff I was pretty much out of the music video around when YouTube came because the business changed dramatically and there was a period, excuse me, a period where, um, budgets were way, way down, labels are doing much better. Now, I don't know that they're spending the salaries that, you know, some, a video commissioner would make a good, a good living and was a high paid executive in the realm of the music video. I think they're making a lot more money now. Labels are, but I don't know that they're paying video commissioners, what they used to pay. So, um, anyways, we would deliver the video. It would get on MTV and as they said, the rest was history. Uh, there you go. That's episode six, commissioning 1 0 1. Hope you enjoyed it. I know I did. Um, we're gonna get into M and M lose yourself. I just saw the Oscars for a few weeks ago and realized I have really good stories about that video, even though it's a little bit of a repeat artist. I figured I'm just gonna tell the best stories I can on this podcast. So lose yourself is a really good story. Lots of, uh, interesting things happened, um, from the, just making the, getting the song, making the song eight mile, the whole thing. So, um, that's it. Let's, uh, let's wrap it up. Um, my name is Randy Sasson. This is the commissioner. And as always, I'll leave you with one last thought sheet. Music is basically just the sound recipe.