NKATA: Dots of Thoughts

NKATA: Dots of Thoughts

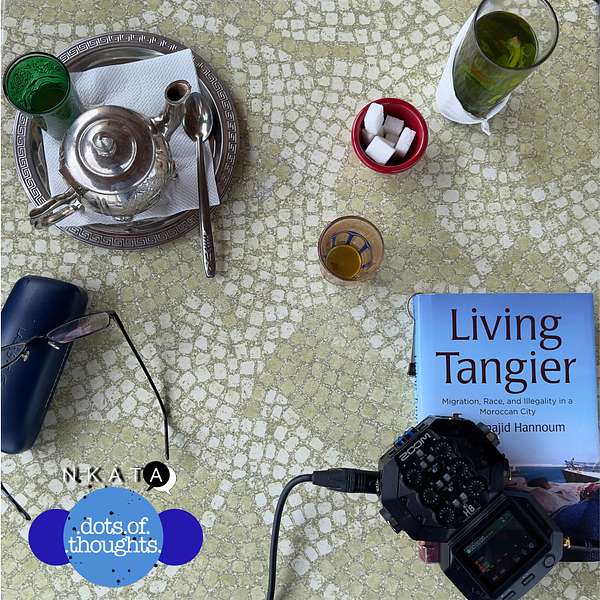

EP18: Rooftop Encounters, and "Living Tangier." – with Abdelmajid Hannoum

During a three-week residency in Tangier, Morocco, my friend and colleague, anthropologist Mathangi Krishnamurthy, and I, Emeka Okereke, had the privilege of meeting Abdelmajid Hannoum, whose book "Living Tangier" served as a springboard for our research and thought processes during our residency in the city, organized and supported by The Minority Globe.

In this episode of Dots of Thoughts, Professor Hannoum shares his intellectual and creative process of translating fieldwork experiences into academic work. We dive deeper into the realities of migration and its impact on the city of Tangier. Hannoum, drawing from his personal experiences growing up around some of the Moroccan children he researched, enriches our understanding of Tangier's intricate history and changing demographics.

Furthermore, Hannoum elaborates on the phenomenon of death concerning the migrant body. This subject stems from his personal experience during his years of research for the book. But our narrative doesn't end there. We also delve into the realm of global cities, exploring how their manicured images often mask the disparities within them. Our observations led us to question the place of Tangier in this global context, discussing its complex identity and evolving narrative.

Join us as we peer through the curtains of this multifaceted city, exploring its various aspects and discussing its complex identity and evolving narrative.

Hi, amazing listeners! Emeka Okereke here. I am the founder and host of this show. If you’ve enjoyed the stories, insights, and creativity we bring to this podcast series, I invite you to join my Patreon community at patreon.com/EmekaOkereke. 🎉

By becoming a patron, you’ll gain exclusive access to my artistic world, including:

• Behind-the-scenes content from my photography projects.

• Sneak peeks of upcoming films, vlogs, and video podcasts.

• Exclusive DJ playlists curated just for you.

• Bonus podcast episodes and a chance to contribute to future topics.

Whether you’re a fan of the podcast, my visual storytelling, or simply love art and creativity, there’s a tier for you. Your support helps me continue creating high-quality content, and it truly means the world to me.

Thank you for listening. Follow Nkata Podcast Station on Instagram @nkatapodcast and Twitter.

See the website for extensive materials: nkatapodcast.com

episode of Inkata Podcast, dots of Dots, and my name is Emeko Kereke. I'm a visual artist, photographer, writer, filmmaker, but also I have my academic side. I'm a scholar and my work is a hyphen of artistic and pedagogical academic projects and interventions. If you have been following this podcast, you already know what it's about, but if this is your first time, you join us for the first time or you stumble on the podcast for the first time. This is one of the two shows that make up a podcast platform that I host and produce as well, and it's called Inkata Podcast. Well, the other podcast is called Art and Processes, but Dots of Dots podcast is a space that allows me to share inspiring thoughts. So essentially, it's a space where I try to expand or make something out of ideas, thoughts, inklings that leave remarkable impressions. So it could be something that was inspired by a conversation with someone, something I read, heard, listened to, or even a project that I took part in. But again, at the center of it is articulating the idea of encounter. When people come together in a context of a shared intent or intention, what are the processes for which they arrive as saying that we have done something collectively, and this episode largely draws from that. So in May 2023, I had a residency project in Tangier, morocco, in collaboration with a friend and colleague, matangi Krishnamuti, who is an anthropologist of India. So we were in Tangier to work on a project about migration movement bodies to think together from this place.

Speaker 2:First of all, to give you a sense of who Matangi is, she is currently assistant professor of anthropology at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Indian Institute for Technology, madras. In the past years, her research areas of interest include the anthropology of work, biopolitics, gender and sexual studies and urban studies. Her book 1800 Worlds the making of the Indian core center economy, published by Oxford University Press in 2018, chronicles the labor practices, life worlds and media atmospheres of Indian core center workers. You know, basically it's anthropology, but she's also very much interested in the idea of the post-mortem, and this is where we find a synergy, and so I met Matangi in Chennai when I was there for the Chennai photo Vienna that was invited to take part in a conference that was organized by the Chennai photo Vienna and we met and since then, you know, we stayed friends and throughout the COVID period, we continue to work together. As of today, we have founded a collective together called Alaila, and it is within this context of the collective that we decided to work together in Tangier. We were invited by this organization called the Minority Globe. We went out there, spent three weeks and, within the context of our research and our working and thinking together, we also met the Moroccan anthropologist, abdel Majid Hanum, but we met him before we met him in person. While I was preparing for this project and was researching and collecting everything that we would need for thinking together and doing this project in Tangier, I came across this book called Live in Tangier, because we wanted to do work around movement and bodies, but also the city the city that serves as the incubator or as the enabler, or, in the case of Tangier and the politics of it, that serves as the border that stops the presence in of these migrant bodies, presence in the sense that that intention to cross over all of that, all of those convolutions, all of those conflations, you know, takes place in Tangier. Alright, so let me give you a glimpse of what the book is about from the abstract.

Speaker 2:So, since the early 1990s, new migratory patterns have been emerging in the southern Mediterranean. Here, a large number of West Africans and young Moroccans, including minors, make daily attempts to cross to Europe. The Moroccan city of Tangier, because of its proximity to Spain, is one of the main getaways for this migratory movement. It has also become a magnet for middle and working class Europeans seeking a more comfortable life Based on extensive field work. Live in Tangier examines the dynamics of transitional migration in a major city of the global south and studies African illegal migration to Europe and European legal migration to Morocco, looking at the itineraries of Europeans, west Africans and Moroccan children and youth, their strategies for crossing, their motivations, their dreams, their hopes and their everyday experiences In the process. Abdel Majid Hanoum examines how Moroccan society has been affected by the flows of migrants from both West Africa and Europe, focusing on race relations and analyzing issues related to citizenship and social inequality. Living Tangier considers what makes the city one of the most attractive for migrants preparing to cross to Europe, and illustrate not only how migrants live in the city, but also how they live the city, how they experience it, encounter its people and engage its culture, work its streets and participate in its event. So that's a glimpse into this book and it was very, very insightful and helpful for our research. So I read the book three days to the time that I took off from Berlin to go to Tangier and my thank you picked up the book while we were in Tangier and, because she was a fast reader, she basically finished it in almost like half a day, I think, or a day.

Speaker 2:This book really helped us to understand the reality of Tangier. It was also able to historicize it for us, to open up our views, without necessarily keeping it peripheral or shallow. It was very much drawn from his own personal experience and personal commitment to the project, to Tangier, given that he also was one of those kids I mean, he came from that demography of kids who eventually would become the Haragha kids, as we learn from the conversation we're going to have with him. But then, coincidentally, he was also traveling in Morocco and he was in Tangier. So what's the time? We were leaving and we had the opportunity to meet with him.

Speaker 2:The conversation that you are going to listen to in this podcast transpired when we eventually sat down with him to discuss the book. But before that, matangi and I have had so much crucial, remarkable conversations and experiences about the city. We have taken our body and our presence to many corners of the city. We have allowed ourselves to soak in the experiences, the vibes on people, to some extent because we were there for only three weeks. But we have also generated our own thoughts. So this podcast is an attempt to extract from the experiences of our time in Tangier.

Speaker 3:Son, are you based out of Tosh?

Speaker 4:Yeah, I live here Because, like, I have a long issue with Tosh, that's fine, so I got a place here. So basically my home is here in many ways.

Speaker 3:Is it still in the alley of the devils? I wish.

Speaker 4:Have you seen that neighborhood? No, they are like Spanish and Italian houses. They are really, really nice.

Speaker 3:So I mean, this is just a formal way of saying thank you for joining us in this conversation. This is something that Emeka and I have been talking about in your absence here, as if we are in conversation with you, almost. So this is quite serendipitous and wonderful. How do I address you?

Speaker 4:Masjid Hanno.

Speaker 3:Can you tell us a little bit about your concerns as you are doing research this is clearly something you have been doing for a very long time A set of central concerns that you think inform both you as a Moroccan, but also as an anthropologist.

Speaker 4:Yeah, I think the main concern that I have been made is research. I try to work on a vulnerable, marginalized population. So I did that in historical work, really about colonized people and the condition that they lived in. I try to really make that story a little bit more now and more vivid, also because there is a lot of distortion about colonial history in Algeria and in Morocco as well. So then I moved to more ethnographic work and some of my concerns again is really about the most, in my view, the most marginalized population and that's basically like African migrants to Europe, and when I say African migrants to Europe I mean like Sub-Saharan Africans and Moroccans as well. So that's basically what informs my research.

Speaker 4:I do connect that to myself in many ways. That's why I think I get some passion about doing it, because it's an arduous work. It's really a very, very difficult work to do. The connection that I make with myself is pretty much the fact that I myself was from really a poor neighborhood. I grew up in poverty. I also experienced a privileged life I shouldn't just claim one thing and not the other and then the use of my generation included myself. We had that concern to live. That was really kind of so pressing and so urgent and so overwhelming as a desire. So I experienced that and that's most likely that's what made me live. And then my own condition as a migrant, because I do consider myself as a migrant, I don't consider myself as a cosmoponist. You know, with this fancy word we go in.

Speaker 3:Okay, but this is just to find your peace here. If you drown, I can save you, no problem. I mean it's a beautiful country. There's people out there. See, we were wrong. They're all women. Ah, okay, so this is just a situation you were speaking about, how your position as a migrant also allows you to connect to your work.

Speaker 4:Yeah, and not a cosmopolitan, yeah so I said that I do also like to share the migrant's condition, despite the few privileges that I enjoy, clearly, and that allows me to connect again with the population I work with. So in many ways, you know, working on this population is also like trying to understand a part of myself as well, but I don't want to be what's the term? Egoistic or whatever the term is. I mean like the work is really about them. You know not about me. Being about them also helps me about. You know to understand myself. You know not the other way around.

Speaker 2:Basically, the one thing that we've discussed a lot is also your approach.

Speaker 2:I remember that, reading the book, I saw the introduction. I mean Matangi, it would be used to this because she's an anthropologist and so she knows but for me it struck me as very, very, very compelling that you took your time to really elaborate on the process and saying you made interviews with them and everything. But when you actually spent time with them and you even numbered, you know, said how many people you worked with and also your process, when the record that came in, when it left, you know, or, and how that was part of facilitating the connection. But then, reading the book, you know it's very tactile, like the words are actually you could tell that it felt like that it's really coming from a place of. I have spent time with you know, and, and, like you said, you know it's about them. But again, one can also see clearly your position in it. So it would be nice to sort of like speak a little bit more on you know what the process was like for you, especially because it was a research that was done over many years, right?

Speaker 4:So process really starts in 2008. I remember I spent that summer here. At that time, the city that we are in right now was quite different, at least like as far as these populations are concerned. There were more Haragah, meaning Moroccan migrants or would be migrants, and then, of course, there were more, like in a, sub-saharan Africans, usually at that time from West Africa, and that has drastically changed. Now we don't see the Haragah anymore and there have been a very few sub-Saharan Africans right now because there are other places where they go to.

Speaker 4:So when I started in 2008, I mean, I started with Moroccan Haragah and they were usually like really kind of children between the age of six and the age of 16. And it was easy to meet them. Usually, you meet them at the port and it was not easy to approach them. Actually, it was the other way around. It was the approach. You usually the ask you for money. That's how the process started. When I started talking to them, of course, I mean like they could be my children at that time in 2018. So there are these generation gap, but at the same time, like their background I knew very, very well. That's the background of the Shanty town in Morocco, as a matter of fact, one time, I mean, at least one kid was exactly from my neighborhood. That's how it started and really started like conversations. I didn't have like a set of questions to ask them, mainly because my approach was really just to do what Clifford Giesigan says deep hanging out, to spend as much time with them as possible, to just let them talk freely. And of course I mean they asked me questions, but they also asked them questions. My questions were not kind of like the sociological type of questions, like fishing for specific information. I really just want the conversation to be quite open and of course I mean I take notes.

Speaker 4:Sometimes I used to tape a record, but then I realized that the recording was a problem Because usually when you try to record them, they start kind of holding back, you know, and they start kind of censoring themselves. So they speak. There are certain things that they don't speak about in front of the microphone. So I got a rid of the tape recorder and we just started talking, you know. So I spent that summer there, but I kept coming.

Speaker 4:I came back summer 2009, again summer 2010. And of course I mean 2010, 2011,. I spent that year here. That was like the fact that they had this whole year, you know, just to spend with kids, most of them by that time they knew very well and one of the major things that City had at that time that it didn't have now, it had that force that was quite open, you know, to the migrants and they used to hang out there.

Speaker 4:Basically, I remember usually like during the day they are asleep, especially in the morning. Usually when you catch them at night, when I say at night, usually around 8, 9 o'clock, you can talk to them from 8, 9, 10, 4 o'clock in the morning, which they used to do. Not only talk to them, but they also talk to each other. It didn't have that group dynamic of me, the anthropologist or the ethnographer, and this group that I'm trying to kind of interrogate. It really didn't have that at all. It was just like in a group. That changes, of course, because, like sometimes, as I said in the book, I come and then they tell me so and so you know, excite, that's the expression they say t'gharb you know, new kids would come and one or two would disappear.

Speaker 4:You don't see them anymore, either because they left to Europe or they went back home. The group dynamic had something very, very interesting that I talk about in my book this modern separation between children and adults. You know, it's something very, very modern. You know, within the group there was no such separation really I mean like the talk and the make jokes about each other and so forth Because the city was very dangerous. You know, I don't know that that's an exaggeration, most likely it's not. You know, it was very dangerous really at night because of the bullies, you know Higara we call them in Moroccan Arabic and also the police, so the older one. They serve as protectors, you know, including myself, as a matter of fact, they can see you that way. But besides that there was kind of a real democracy within that group, meaning everybody basically is equal to everybody in terms of talking and joking and so forth.

Speaker 4:You know, when I go back home I do different work Basically, I take notes.

Speaker 4:You know, I have a great memory basically, which had to do with the fact that when I was a student here, like really primary school and also high school, I was very interested in Arabic literature.

Speaker 4:I used to learn a lot of poems by heart and also like prose, you know, like really these beautiful texts, you know so, immediately as soon as I get home I write my interviews and so forth, you know. So that's basically the process, the process of thinking all of that. I didn't do it in the field, meaning, like all these concepts that I talk about or, like you know, separation between adults and children, or raised concepts of race or, I don't know, illegality, all the stuff that I talk about in the book as concepts that came out later, like when I went back and I started reading other ethnographies but also other books about, you know, sort of theory, also project theories and so forth. You know Some of the stuff that were said that you didn't write them down, something that you didn't put down either because somehow you didn't think it was important or just you forgot, you know. So it comes back to your mind, like you know, throughout that process of thinking, really conceptualizing the project.

Speaker 2:There is a way that you wrote the book, the entire book, that really accounts for your presence every point in time.

Speaker 2:It's almost like in a very tactile way I keep coming back to this world, tactile Like I keep thinking at the back end all the time when I'm reading. You know you've talked about how much of the book comes also from your own personal experience, but you also mentioned that those kids are also somehow your reality at some point. So is it possible to sort of like talk about how that has facilitated you being there in body and also how that helped to say, maybe direct your, the way you move between them and, to some extent, that they were able to trust you, that they were able to, you know, forget that you were there. They were able to forget that. You know you are doing this because that's actually the sense we get from the book that at some point they just forgot that you are not actually one of them and you were able to sort of like and yet you were able to manage that all through while you are with them.

Speaker 3:And I was thinking as you were speaking. You know the part where you speak about the category of the child being a product of European modernity is so compelling and so adding to America's question, I also want to know you know it's not a small thing to decide to do work with children for an ethnographer. It's fraught with so many considerations and in your disposition then, how did your own understanding of children that you were working with? Move for you as well. Just to add that.

Speaker 4:Well, there are two aspects to this question. I mean the second one, which is linked to the first one, of course, the question of children. When this phenomena of Harraga that I'm really meant pretty much like very young people, including like children who try to cross when it came out late 1990s and early 2000s, it was quite sensational in Morocco. It's a people who just talk about Harraga in kind of sensational way, about these like unbelievable children that cross to Europe and get under the buses and so forth, so that in itself, I mean it was the reason why I got involved in that.

Speaker 4:That's why I started the chapter by Satish Nofinichi. Say my brother, what can the child do that even lion cannot do? It was quite shocking to me, but also to Moroccan society as well. You know. I remember my sisters would talk about that and everybody would talk about that and they wanted to understand that. The other part that I said and it really should be just, you know not my reason, I mean it's a reason, but not really the most decisive one it's, as I said earlier, the fact that I did identify with children. You know, because by time I was 16 I didn't leave that condition anymore, mainly also thanks to migration. My economic condition has really drastically changed because my father moved to France and he did very well for himself and so forth.

Speaker 4:But that time period, you know, till age of nine, ten, I did see myself like myself and, as a matter of fact, when I look at my pictures, like at that time, I used to dress like that as well. So what helps me connect with them is the fact that they were also from like, really, my social background. You know that they could, I could speak their language. You know, even though, as I said, like in the book, that their social world is not really mine and so forth, but they had to connect with them on on something self-fundamental to them, and it's not something that they had to work on, it's something really happened, spontaneously, most likely because of my memory was triggered and they could go back to, you know, to that mindset when I was like nine or when I was eight years old, and you could feel that. You know, because children are extremely perceptive and intuitive, you know, they can feel everything. There are times when it really surprised me when I was there. Surprised me like how they could, either because I went away or because, you know, I was busy so I would not go there for a few days.

Speaker 4:And then I go, and then the you know, they keep asking, you know, and me, the other, they say I'm me, or they say Ustaz and me it means uncle. It has to do a little bit with age, of course, but it's an expression that, like that, people use. You know, it's like same brother in some ways and Ustaz is just like. It's also an expression that's quite common. They say it means professor, but it really officially it means professor, but it's used to not in the sense of sir, but just some kind of title that really marks respect, but it doesn't mark distance. You know, ustaz, where have you been? We haven't seen you in few days and that's quite surprising. There are times when it really feels like family. I shared meals with them, especially in dinner, son, usually I would buy it actually.

Speaker 4:So basically what I'm saying here is, like you know, sometimes I said that to my students, they said, like I can tell you what to do, you know. You know we can read books about field work and field know. Some join us and other, but most likely it's not going to help you a lot because once you are there, the every situation is completely different. You know, and you can click and you can not click. Language is important. It helps you, you know, but there are other factors, including, like your own personality, whether, like you, can inspire trust or not. You know the work, as I described in my book, it was really tiring, it was extremely tiring and at the same time it was really a delight to work with the kids, many like enjoyable, even in the kind of conversations we had or the kind of jokes they make or the kind of you know events, sometimes the you know they invite me to go to, and so forth.

Speaker 2:You know one of the things I've been I think about in a lot in intellectual, academic work is the, the distance, the disparity between you know when people who have not lived something you know, but they go to do this field work because they feel like it's an in form of empathy towards that, that, and then they go to do it yeah how that work comes out, as opposed to someone who every time they are there, they are constantly tapping into something they have lived and there is a set of a language within the level of connecting that you cannot really explain, but you can somehow see it in the work come out.

Speaker 2:So I've always been interested in artist intellectuals who, for lack of better word, first of all grew up like street and then slowly walked their way into the academia and the kind of work they make and how that often relies on the experiences they had from outside the academia. Actually, I don't know if you can relate with this, Mathangi.

Speaker 3:It's a category that's so much debated, even sort of in intellectual circles. The idea was who gets to do what work and this category of the native ethnography in a way, but what you are talking about in America is also very specific, the idea that access to academia is such a guarded thought.

Speaker 4:That's correct.

Speaker 3:And people who are able to make it through those kinds of garrisons. Where do we make a case for life experiences constituted? It's something that you and I have debated a lot, which is theory in the global north, experience in the global south, and then you map one onto the other, and this has been the kind of flow of a neocolonial knowledge mechanism. So I completely know exactly where you're coming from in this and in a sense, perhaps I wanted to also talk to you then about doing this thing back and forth. How does it feel to then translate it?

Speaker 4:Back and forth between the experience and the academia.

Speaker 3:How does it feel to translate it then, before I can see it in various parts of the book? For a North American anthropological audience, partly, but I must say what really distinguishes Living Don't Share for us really is how I read it in two settings.

Speaker 3:Two days back to back in a sense. So besides that, and a mech and I had a conversation about the introduction and I said, yes, this is familiar. I can see how setting it up in relation to conversations is a practice I'm familiar with. But how you write the fieldwork in that fashion, how does it feel to translate it? What you know, the anthropologist's process of going back and writing?

Speaker 4:Yeah, yeah, well, I mean, that's a great question as well. So there are two processes really of writing, you know. There is the first one when basically, you just had these conversations and then you write them down. It seems the easy one. Actually, it's very interesting you said that because just yesterday I was looking at this note because there are lots of stuff. You don't include every interview, every description that you wrote when you just had the interview or you just saw what you describe. Of course you have to do some editing and you publish as is, you know, and they said, like it would really make maybe a greater book because at least it would not have this kind of like intellectual, like you know, jargon, sometimes concepts, you know that you say, to use like a metaphor of an advisor of mine actually said this like what's this jargon that you know, you see, is like like hair on a soup, you know, so, so.

Speaker 3:It's a very powerful image. I'm never going to be able to forget that when I'm writing now.

Speaker 4:So there's that, and then there's the second part, which is basically usually that like when you go back and then you have to read more and you have to read some stuff about, as I said earlier, about concepts, about theories, about other ethnographies that people have done somewhere else, and that's a second, you know, type of process that adds to the first one. You know, because then you are doing something quite different, you are interpreting yourself in many ways, you know, you are reading your notes and as if those notes cannot make sense by themselves, you know. So you are trying to give them a new sense. You know, because anthropology, I mean it has these characteristics of you cannot just write, you know, specifically or locally, you have to engage with people. Who did, you know, that type of work.

Speaker 4:When I had to read, you know, and of course I mean I had to kind of like conceptualize. It was also marked by a personal experience that I don't talk about in the book, that maybe it did help me to write the way I did. And that experience, because the book was written very fast, I mean I did research for quite a long time but because of teaching, but also because of other projects that I was doing. I didn't get to it Till I had this experience. That was back on February 9th you know, 2017, I had a blood clot. You know that was going to my brain and I was going to have exactly the same experience that you had you know.

Speaker 4:They even cut it a little bit late, as a matter of fact you know. So the chances to get it out were like 50%, you know. So if I waited just a few days, or maybe a week or two weeks, maybe it would have been too late. And then, of course, I had to go through a surgery too. As a matter of fact, one of them was to get the blood clot out, you know, and the second one was really to kind of close the heart that created the blood clot. Basically, I had a PFO.

Speaker 4:PFO is a small, you know. It's a small hole in the heart that everybody has when they are just born, but the heart gets closed as soon as the baby starts breathing. But 25% of the population of the earth don't have the chance, so basically the hole stays open and that may cause, you know, a blood clot. You know. So most of people don't know it. Most of people have normal lives until something happens and then they realize like, wow, you know done so. I did that. That experience. It was extremely painful.

Speaker 4:as a matter of fact, it was you know, the only time that you really have to face, you know, the possibility of your death Immediately after. It took me three months to recover. Immediately after I recovered, in March I remember. So I went back to those notes Before July 4th, I was pretty much done with manuscripts.

Speaker 4:You know I work on the concept of death now I mean the death of migrants, as a matter of fact. So when you have an experience like that, you know I mean of course some people have much closer experience with death than the one I have, but it's sad, it helps you put perspective on things, you know, including the kind of work you do, I mean the kind of life you have, kind of relationships you have with other people and so forth. So I went back to the, you know, to the project. So I finished it, you know, as I said, and then I was left with something that in many ways prompted me to finish early, but I didn't deal with it. You know which is basically the concept of death. You know that I'm working on now.

Speaker 4:I think I do mention in the book that this type of migration is characterized by high rates of death. Did I drown in? Did I die at the police? Did I in the deserts, you know? Did I in the streets sometimes, you know, whenever there is gunks, violence, and so that that topic itself came from this experience, as I said.

Speaker 2:But reading the book one can see that there is a lot of care, attention, and you know I would. I would come across all the time these feelers. There are many books that I've read that is able to sort of pull that off, where you use, like one sentence, feelers to communicate a certain kind of emotion but also to show exactly where you are at that point in time. I'll give an example. There's this passage where you said that, or this part where you said that one of the guys you were speaking with was calling, saying something like Azizos, you know, and then he said it and he laughed.

Speaker 2:And then you know, as an extension of that sentence, you said something like he laughed like to invite laughter from you, and at that point in time I could see exactly the awkwardness of that situation, how you are sort of like positioned, like thinking this is not funny, but you were also able to communicate it in a way that you can see his position, but you can also see your sympathy with that position. So there's a level of emotion there, but there's also a level of distance and this is something that I saw that you are using this one sentence way of sort of like communicating this, which I found very, very, very interesting Because also, the book is very brief in the sense, but very expanded. You can read in between the lines a lot, and that's amazing.

Speaker 3:Following up from that, I think the fact of there was something remaining, especially when you spoke about migrants' own sense or not, sense of death, also gave me a sense that this was something that you had put away to think about later, in a way. So would it be possible for you to tell us how you're thinking about it now, because I know you're also in the middle of field work or at the end of it what you've been working on and how you're thinking about it after so many years as well.

Speaker 4:I'm at the beginning of it, because the phenomenon of death of migrants, it can be tackled ethnographically from different angles. I mean, it was years so I go to Fnidak, I haven't gone to Wizda yet, but I have to go to Wizda, nador, next month, june and July. I'm not thinking about conceptually as a matter of fact, I even avoid reading about. I mean there are few, not a lot stuff about death, few by very, very few anthropologists, there are few by philosophers. So I try not to read about that. So they said like I do it ethnographically, meaning like it has different aspects. One of them is you interview the migrants themselves about this. You get a little bit disappointed in the response because there aren't many. The responses are just a couple, really a couple of sentences, which is basically when you ask about the possibility that the person may die in the sea, they will tell you well, if God has decided that to a beast, you know, or another answer close to this.

Speaker 4:As a matter of fact, they will tell you that if it's my destiny, you know a beast. So that's really the answer that you get. But there are different aspects, you know how different ways. How do I do this? One of them is you talk to friends of the deceased, you know, because then it's not really an abstract, because that is an abstract and that's for children and for young people more than for us, you know. But when a young person, or even a child, is hit with news of the death of his friend, they have completely different take on us, you know. So meaning like the, they don't just see it as a concept, they see it as really something that happens close and that may even happen to them as well. But there aren't many people, you, whose friends has passed away in the sea. So what you do is, like you also look at the, how the NGOs talk about that itself, how the newspapers talk about about that itself, how the EU agencies talk about it.

Speaker 4:And it's very interesting on this aspect, because usually they really talk about death as a number. You know, they don't talk. I mean, just like you know, 19 migrants died today on their way to Tarifa. So there are no faces, no narratives, nothing. But that in itself is very, very important. That's in ethnography, to do there as well, on this concept of death or this issue of death as a number. And then we have, since June 24th 2022, we have really kind of like a new phenomenon which is basically like the families of the deceased, you know, or they don't even call themselves the family of deceased, I mean, they call themselves the family of the missing. I say the deceased because the migrants themselves say deceased, you know, and they say that's because when the migrants crosses, if they don't hear two or three days maximum, the migrants conclude that the person is dead you know.

Speaker 4:But families, of course, I mean they have this hope that the person may be just missing, like they may come, they may be, just you know, they have not called back, et cetera, et cetera. So that itself is another population, it's really a new population to the field work on. That's what I will do next month and the month after, meaning June and July. And then there is another aspect, because that's why I said this is just the beginning. I have to do it also, like in Southern Spain and in Southern Italy as well.

Speaker 2:In the book, I noticed that you keep coming back to try to delineate and return to this idea of the death. We've been moving around in Tangier here as well, we've been meeting some migrants and we've been discussing with them, and one thing that we keep coming back to is to understand, really, what makes one want to cross, despite everything. You know everyone have their take on it. I think that the Tangier that we've come with, that we've met now, is a Tangier of 2023. And that's a lot that's shifted especially. You also touched on the fact that the narrative was shifting. You know, perhaps I don't know how you've experienced Tangier now in relation to especially because you grounded it on all of this work within a Tangier that is also having this neoliberal dynamics to it. You coming back here now, I don't know if you've seen some shifts already that you think perhaps tending towards what you are thinking or deviating from that.

Speaker 4:No, there is a huge shift compared to even 2015,. 2014, a little while when I was doing really like the intensive field work I was doing in 2011. It's quite drastic. The first time that changes almost everything about migrants here in Tangier is the fact that the port moved to L'Xarxerre, which is 35 minutes away from here. And then this port I mean basically it's a touristic port. It's impossible to cross from this port the way it used to be before. You know, tangier is not the gate that it used to be anymore because of this change of ports to L'Xarxerre. L'xarxerre, I mean in L'Xarxerre, you find more migrants. I mean the migrants that used to come here. They go there now, even though the security is extremely tight, you know. But there are more possibilities there because you have these ships that are commercial that if you are lucky or if you are really kind of extremely intelligent to get to one of them, you may have the chance to cross.

Speaker 4:There are a number of reasons why the port has changed. One of the reasons not the reason was also to kind of clean up the city from the migrants, and that has worked quite well. So there are very, very few migrants compared to before 2016. There are some events that also happened. As a matter of fact, one of them happened in 2017, when a kid died and there are tourists' bus. It was in downtown, like next to the Cornish actually, and that creates really kind of a shock that made the authorities more concerned about kids hanging out in the city. So the situation is very different from what they describe in my book, right now.

Speaker 4:But it doesn't mean that the problem was solved. The problem was just relocated somewhere else, to L'Xarxerre, and then to Fnidaq, especially in the mountains of Fnidaq, where you have like forests and there are really like camps of migrants living in the forest and also, like the migrants risk really kind of harsh present sentences now if they are caught there, you know, up to three years, you know. Yet at the same time, I mean in Tungier, you still have like few and you still have like people who cross from Tungier, but they cross a little bit differently, usually through smugglers, you know, and the smuggler costs 3600 euro. It's sometimes very, very expensive for our migrants, you know, and therefore, because it's expensive, it's a rare occurrence, you know, not many migrants can afford that much money to cross.

Speaker 3:In which case, in light of you know what you've been telling us over your long years of chronicling these ships, in your estimation, what would you say is the current narrative about Tungier? What is Tungier now? It's something that we have been attempting from various aspects. It's what Emeka has called a multiplex of a certain kind. It presents certain possibilities, but no sureties. What do you think is the current narrative of Tungier?

Speaker 2:Especially sorry, especially because you know thinking about it now.

Speaker 2:You said that the problem has moved away, so it is also part of that shifting narrative of Tungier. But we can also think of that, you know, bringing the possibility that there is a void now which now allows things to take different happenings in a like, you know, multiplex way. And this is something we've experienced also that Every where we go we meet some migrants and each and every one of them have a different narrative. Now We've met a migrant who is the archetypal expert, you know, and everyone says he is the only one out of everyone. He's a Nigerian who has made it into Nigeria and they say like there's no one else, because he works at a tech company here and he was able to invite his mother from Nigeria to visit him for two weeks and then go back, and that is only one strand. But he tells you also that he comes from that place of when he didn't have papers and all of that, and that's just one. So many tangents to it. So I wonder how you are thinking about you know all of that now.

Speaker 4:I don't know whether there's just one narrative for Tonsir. I'm sure that there must be several, depending on to whom you're talking. You know, I think the official narrative from what I can conclude from the press, from even, like now, political statements by officials and so forth about Tonsir, it's really it's a city that they want to put at the forefront of Morocco. You know, sometimes people use the concept Merroir or Mer. You know this is basically like, and therefore this Mer that looks to Europe, it doesn't look to Africa, as a matter of fact, it turns back to Africa. It needs to be as European as it can be and therefore you can see, I mean like most likely Tonsir is the most Europeanized city. You know, as a matter of fact, someone said that long time ago in 19th century Miege historian. But now is more than before. You can see that, like in the building, you can see that in the restaurants, you can see that even in the type of migrants, because I use the word migrants to include not only Sub-Saharan Africans, anybody who comes here, you know, for a living, whether they are from Sweden or from the UK or from wherever you know. So again, it's a city that wants to present as really you know the face, you know that first thing that you see when you come from Europe. Therefore, it's as European as it can be and, as I said, like it's European in its architecture. It's here. As a matter of fact, it's very interesting because even the Qasbah Qasbah, which was like the most like traditional, authentic part of the city itself, has become very Europeanized in two ways. One, it has become really an Orientalist. You know part of the city that corresponds to that concept of the Oriental. You know house that we can read about or sometimes look at on paintings and so forth. And second, it's populated by really usually like privileged Europeans. Most of them are French.

Speaker 4:That's one narrative and they think in my view it's really the most important one because it's the official one associated with government, with state and so forth. And then, of course, you have other narratives about city as a hub for culture and art and so forth. You have that as well, and people who have this kind of narrative, usually they are artists themselves and they kind of connect the presence of city to its past with this, like famous artists that pass by here. You know Picasso, matisse, Monet, etc. That's why you find this kind of proliferation of Moroccan arts. I don't think that you can find it in any other city but Tungier. Of course you find artists and galleries, and all that in Casablanca, but in my view Tungier has more artists, you know, in Morocco, but also it has European artists as well and even Latin American artists who live here. They are narratives of tourism also.

Speaker 4:You know all kinds of narratives, not just one. So I mean the old narratives that city had. It's still alive. I mean meaning before 1999, which is like a major date in the history of the city because that's the beginning of the reign of Mohamed Seks, who really focused on city and he wants to transform it in the way that they just described, meaning like very modern and very connected to Europe. Before that it was a very marginal city, maybe the most marginal city, like in Morocco, and it had the narrative about Tungier at that time was like you know, it's a city of drug dealers, a city of sex work. You know it did have the narrative also, like, of art and culture, but even art and culture were connected to drugs and sex actually. So that narrative is still alive and well, you know, and it doesn't seem it's going to die anytime soon.

Speaker 2:You know you talk about how Tungier is a mural in a way but we're also thinking about it.

Speaker 2:Does that mural infiltrate all of Tungier or is it? What do you think? Because there's still a divide between how the shores are treated as opposed to the inside inner part. So you talked about Casbah and even the Marina and the Marina, but also when the moment you move away from that and move into this place is as if even Yemo was in the day that the architecture, the everything does not in any way will you to go inside. It keeps you. It keeps you in an axis along the shores. It's only when you go out and go up that you see how expansive Tungier is really. So I was wondering if there is, there isn't a concerted effort to keep that mural in just at the shores? Yeah, no, that's a very interesting question.

Speaker 4:I don't know if I can answer this. Actually, I can speculate, but I'm not sure my speculation will be really informed. My first reaction is like what you said is true on almost everything, like in the world, I mean like. Second, new York, and New York has parts of them.

Speaker 4:There is New York, manhattan you know, and then of course there is the Brooklyn, syria, that even in the imagination of Americans they are less in New York than Manhattan. And then of course you have like neighborhoods in New York that look pretty much like like a third world country, you know. So you have same thing in Paris. I mean like you have Paris, and then you have in Tungier. You have that too. I mean like you have the face which is pretty much like what we see. I mean like not Kasbah, I mean like what I call downtown, even though Tungier has, you know, a couple of downtowns, not one, but this one is the main one, meaning the Boulevard, it has one like Malabata, you know. And then what you saw, like a little bit outside of the of this center, that doesn't look as European as the rest.

Speaker 3:I just want to follow up on your speculation a little bit. You're right, I mean, this is true of most global cities in a sense there's a point that they seek to manicure to present a particular view to be sold.

Speaker 3:However, in our conversations we have been struck by the location of this manicure, that it's not incidental that we are at the border of Europe and that's the part that is Europeanized. And one of our acquaintances told us you know, quite lovely, he said. I said I came from the airport and the roads were lovely, there were palm trees. And he said, you know, it's a trick, we pull just that one road that comes from the airport into this downtown.

Speaker 1:That's the manicured part so you're not drawn to, so maybe also.

Speaker 3:Oh, there's a cat.