High Visibility: On Location in Rural America and Indian Country

High Visibility: On Location in Rural America and Indian Country

What The Sound Carries: Raven Chacon

Today we have the chance to speak with Raven Chacon, and to learn more about the experiences that have shaped his work across a variety of forms – from his music compositions, to his visual scores and installations, through to his leadership in the Native American Composer Apprentice Project and his piece American Ledger No. 2, currently on view at the Plains Art Museum.

Raven Chacon's artist site:

http://spiderwebsinthesky.com/

This conversation moves across an array of lands and traditions– from Navajo Nation to Aristotle’s Lyceum, from string quartets to heavy metal – and a presence that connects many of the pieces Raven discusses is his time as a guest with the Water Protectors at Standing Rock in 2016. Afterwards, he reflected on the experience, he wrote this:

“The camps became the imagined microcosm of a North America where we were still the majority, self-sustained and self-governed, no other direct action than simply being alive and retaining our ways. What became apparent—even in the short time I was there and under the shadow of militaristic surveillance—was a shared experience: remembering one’s identity, while at the same time re-imagining who we aimed to be. What was achieved there was not a funneling of a pan-Indian sameness, but rather a radial explosion of every potential dreamt history.”

Raven Chacon is a composer, performer and installation artist from Fort Defiance, Navajo Nation. As a solo artist, collaborator, or with the Postcommodity, he has exhibited or performed at a wide range of institutions and spaces including the Whitney Biennial, documenta 14, San Francisco Electronic Music Festival, Chaco Canyon, and The Kennedy Center. Every year, he teaches 20 students to write string quartets for the Native American Composer Apprentice Project (NACAP). Raven is the recipient of the United States Artists fellowship in Music, The Creative Capital award in Visual Arts, The Native Arts and Cultures Foundation artist fellowship, and the American Academy’s Berlin Prize for Music Composition.

Works and connections mentioned in this episode:

// Native American Composers Apprentice Project (excellent feature here by NPR Performance Today):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V0U_C2iKIGY

// An Anthology of Chants Operations LP:

https://ravenchacon.bandcamp.com/album/an-anthology-of-chants-operations

// The Ears Between Worlds are Always Speaking installation in Athens, Greece:

http://www.postcommodity.com/TheEarsBetweenWorlds.html

// Dispatch, a collaboration with Candice Hopkins:

https://disclaimer.org.au/contents/unsettling-scores/dispatch

// STTLMNT, An Indigenous Digital World Wide Occupation:

https://www.sttlmnt.org/

// American Ledger No. 2:

http://spiderwebsinthesky.com/portfolio/items/american-ledger-no-2/

// For Zitkála Šá series of prints at Crow's Shadow Institute for the Arts

https://crowsshadow.org/artist/raven/

// Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies

https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/hungry-listening

// Radio Alhara:

https://worldwidefm.net/show/ww-palestine-radio-alhara

Hello, you're listening to high visibility. This is a podcast produced by art of the rural Plains Art Museum welcomes into conversation artists, culture bearers and leaders from across rural American Indian country. It's offered in conjunction with high visibility, collaboratively curated exhibition, currently on view at Plains Art Museum through May 30 2021. My name is Matthew Fluharty. And I'm organized. In the months ahead, I'll be with you, along with other posts from the Plains Art Museum. As we share the richly divergent stories, lived experiences and visions, folks across the con. You can learn more about the high visibility exhibition by heading to plains art.org. We also welcome folks to check out the High Visibility site at in high visibility.org, where we offer show notes and transcriptions alongside further information on the individuals and work discussed here. Also, depending on the podcast platform, one can view and directly link to artists work while following along to the conversation. We're grateful for the support of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts in making this endeavor possible. And we welcome folks to check out and subscribe to these conversations on their favorite podcast platforms. Today, we have the chance to speak to Raven Chacon and to learn more about the experiences that have shaped his work across a variety of platforms. From his music compositions to his visual scores and installations through to his leadership and the Native American composer apprentice project, and his peace American legend number two, currently on view at the Plains Art Museum. Along the way, we also have the opportunity to sit and listen with Raven, as he shares the stories and creative practices behind his recently released and highly acclaimed album, an anthology of chants operations. so grateful for ravens time and generosity. This conversation moves across an array of lands and traditions, from Navajo Nation to Aristotle's Lyceum. From string quartets to heavy metal, and a presence that connects many of the pieces Raven discusses his his time as a guest with the Water Protectors at Standing Rock in 2016. Afterwards, when he reflected on the experience, he wrote this, the camps became the imagined microcosm of North America, where we were still the majority, self sustained and self governed no other direct action than simply being alive and retaining our ways. What became apparent even in the short time I was there, and under the shadow of militaristic surveillance was a shared experience remembering one's identity, while at the same time reimagining who we aimed to be. What was achieved, there was not a funneling of a pan Indian sameness, but rather a radial explosion of every potential drempt history. Raven Chacon is a composer, performer and installation artist from Fort defiance Navajo Nation. as a solo artist collaborator or with the post commodity collective, he has exhibited or performed in a wide range of institutions and spaces, including the Whitney Biennial, documenta 14, the San Francisco electronic music festival, Chaco Canyon, and the Kennedy Center. Every year, he teaches 20 students to write string quartets for the Native American composer apprenticeship project. Raven is the recipient of the United States artists fellowship and music, the creative capital award in Visual Arts, the native arts and cultures foundation artists fellowship, and the American Academy's Berlin prize for music composition. So without further ado, please get comfortable and enjoy our conversation with Raven shuckin. Raven, welcome to the high visibility podcast. It's a real honor to have you with us.

Raven Chacon:Yeah, thanks for having me.

Matthew Fluharty:It's an honor to have you with us and also an honor and have American legend number two, on view at the Plains Art Museum right now for the high visibility exhibition. And I'm grateful for our time together to sort of think about that work, but also think about how it's situated in the larger arc of your life's journey in your creative practice. so grateful again for your time. You know, and I'm what I'm wondering just as a way to kind of settle into the conversation is just sort of asking, like, Where did you grow up and what were some of the early experiences, early influences that you had Your own developing evolving process as an artist.

Raven Chacon:Well, I grew up in a town called Chinle, which is right in the middle of the Navajo reservation. I lived there for about the first six, seven years of my life. And that's the place where I'm my mother's from. And my father's from northern New Mexico. And so, around that time of six or seven, the family decided to move to Albuquerque. And I've lived in Albuquerque, most of my life, I would say I, I call that my permanent home. But a lot of my my mom's side of the family lives still out and chinley and chinley is a place I visit at least once a year. I mean, definitely, definitely more when I can, when I go teach the students for the Native American composer apprenticeship project, right teaches kids to write string quartets at the at the high school there and traveled to, you know, some of the other high schools on the Navajo Nation and Hopi nation. But, I mean, obviously, it's a very rural place. It's it's a desert, much like the rest of Arizona and New Mexico. And there wasn't a lot of I mean, I don't know how much a young kid gets exposed to music and art anyway. But really, what there was, was, you know, the radio, and a lot of family members listening to heavy metal, you know, hard rock and anything with guitars. So I think that definitely had a musical influence on me and in some way. In addition to that, my my grandpa, he's, he sings a lot, he's, he sings all the time, Navajo songs. I think that too, you know, I think I think recognizing, making music was was there immediately, and just listening. So it wasn't till later on, though. And when the family moved to Albuquerque, that I was studying piano, we had a piano teacher, and that gave me more of a basis of this kind of formal music education. I mean, I still play piano to a bit, you know, to a degree, but what it did give me is this understanding of notation and understanding maybe how the other instruments work, you know, this kind of grid of notes, the scale, you know, led me to think about playing the guitar, strings, other instruments. And same time to you know, eventually wanting to form some kind of band, heavy metal band or something, you know, thrash metal band, and, and it just not coming out, right, it's sounding like noise, you know, and some of that, due to just the quality of instruments I had, you know, you don't, you don't know how to replace a string or something. So you just put the wrong string on the guitar, tie them together, and it starts at sounds really, really bad. But you just keep going and sounds like, it sounds like something you never heard before. And I think more than anything that kind of stuck with me that the music can be abrasive can it cannot fit into a meter. Granted, I was trying to play maybe a meter trying to play virtuosic players, but but now it's like, yeah, the string becomes really loose and, and doesn't sound normal. And I just, I just like that sound. And and so later than, yes, I decided to study music formally in the university, and figured out what I was doing. Just for the sake of this conversation as an educational document that folks will hopefully come back to, when they're seeking to learn more about your work. What was the first heavy metal band that you were in? I mean, the names are so juvenile, I'm embarrassed to say but and it's the kind of thing where you know, a few of you in the group or in the neighborhood do something and you call it one thing and a different configuration happens and you call it something else. But you know, I'm to be honest with you, I'm to kind of kind of too embarrassed to say these names, because I trace it back. But yeah, they're very juvenile ugly names, but it's even more tantalizing that

Matthew Fluharty:we're left in the space of Unknowing.

Raven Chacon:Yeah, yeah, they're, they're bad. They were bad. But eventually, there was one I did called low subliminals. And that was like, it was like, I don't know, like this kind of like surf music, but, but all of us were interested in like thrash metal. So it sounded very, you know, experimental in that way that it was, it was trying to be very fast, but it didn't, we didn't distort the guitars, you know, the speed picking, and I still play I actually still play with those musicians. Now we have a band called tenderizer. We still make music together. But we also make experimental improvised music in Albuquerque. And I've been playing with these guys for Yeah, like 25 years or so. And from the beginning, were you sort of the individual in the group who was recording and thinking about the sort of the sound document as well for for these performances, maybe we, I have to find some old tapes, we did make, you know, take a like Walkman recorder out there. I mean, we this was the other part of this was, sometimes we wouldn't have a place to play. So we would drive out to the west side of Albuquerque, there's this kind of Cliff that just drops off. And there's these sand dunes.

Matthew Fluharty:Yeah, thank you. I'm really left with that sense of how sound would echo across that space in in western Albuquerque. I mean, this is an aside but man like the basement punk shows in the Midwest are like the exact opposite. It's just like total Yeah, notice. Yeah. I can only I can only hear the one year is because of those because of those experiences. But Returning to the podcast, I think that's an element of your work that I think feels really notable for a lot of folks who, who write and write about the wide array of practices that you have is that there is. I mean, what's interesting to me is that I'm about to use words to explain genres of music. And something about just the way that as a whole sort of body of work your practice exists, is that I think it often for me, as a single listener, asked me to challenge what my, my even my linguistic associations are with specific genres, you know, and that those genres themselves can be oftentimes described in ways that are really reductive and kind of close off, the sorts of like, flood tunnels between ways of hearing and ways of playing. And a kind of an element of that, that I'm really interested in learning more about is that there are these various forms of sound installations and music and performance elements in your work. And you're also an active central participant in the Native American composer apprentice project. You know, so we're talking about those early experiences that you had as an artist. And in that there's an organism you're working in where you're, you're also not only giving back to the community, but you're a mentor, you know, that there's a cycle to this creative practice in your work that is generative in so many regards. So how did your engagement with kneecap that's the acronym? Um, how did that begin?

Raven Chacon:Well, it it had started in the year 2000, the, the kneecap program, and it was a part of the world still is a part of the Grand Canyon Music Festival, which has been going on since the 80s or so. Or, you know, every summer they go and put on a big Chamber Music Festival and on the Rim of the Grand Canyon, and around the year 2000, they realized they should have some kind of community engagement. So thankfully, they thought thought about that and started this program, just with one high school teaching Tuba City thing was Tuba City High School. And had collaborated with the composer Brent Michael Davids, who is Mohican composer. And so he, I give him credit for founding that, that project. And I think he only did it for one year with five students. And in subsequent years, they had other composers, some native, some not coming out to that place. And I had become on the radar around 2003 2004. I think maybe Brent recommended me. And it, it worked out great, because I mean, I'm sure they were doing a great job, but I'm from this community. So I definitely know where the students live, what the conditions are, can speak their language to an extent. I mean, I'm talking both DNA language and, and the language of, I don't know, heavy metal, which is what the kids are still listening to out there. You know, and yeah, I went, I mean, I gotta be honest, I didn't quite know what it was. either. I knew the project was to write string quartets, but didn't really know who the host organization was, or what the audience still was going to be, you know, we think of a concert at the Grand Canyon. And I'm thinking, well, maybe we're just playing for tourists at the Grand Canyon. And so always skeptical of that kind of thing. And I said, I told the organizers, I said, I would like to do this, but I want to expand it and have one of the schools be chinley High School, you know, where I grew up. And, you know, for the reasons I also just want an excuse to go visit my grandma, you know, they hang out and, and cousins. And so that that's been it every year since then. So this is year 17. But some beautiful things have happened. We've been able to expand the project at its peak was servicing seven schools, I think, you know, five on the Navajo Nation, one at the Hopi, the Hopi High School on Hopi nation and salt river Pima High School down near Scottsdale. Scottsdale is is originally Pima land. And I think at its peak Yeah, we had like almost 40 students one year, each writing a three minute composition, which was totally intense for me. But the other beautiful thing that has happened is that very first year, New Year 2001 of those five students, his name's Michael Begay. He's become my assistant. And he now teaches co teaches half the students with me. And so he's become quite a, I mean, he's become my own kind of apprenticing under me learning composition for me, in private lessons, and then getting some experience teaching by doing this project. And yeah, I mean, the the situations are different with every school, some of the schools have no music program or arts program at all. And, you know, that's, unfortunately, not really surprising. It's, you know, a lot of schools across the country don't prioritize music or art. Some of the other schools do have a music program, they have amazing music programs, some of the best music teachers, I mean, I wish I had these, these professors or teachers as my music professors, but um, I believe that the reason they have good music programs is because they have a good sports team, and they need a marching band, you know,

Matthew Fluharty:oh, to support, that makes sense.

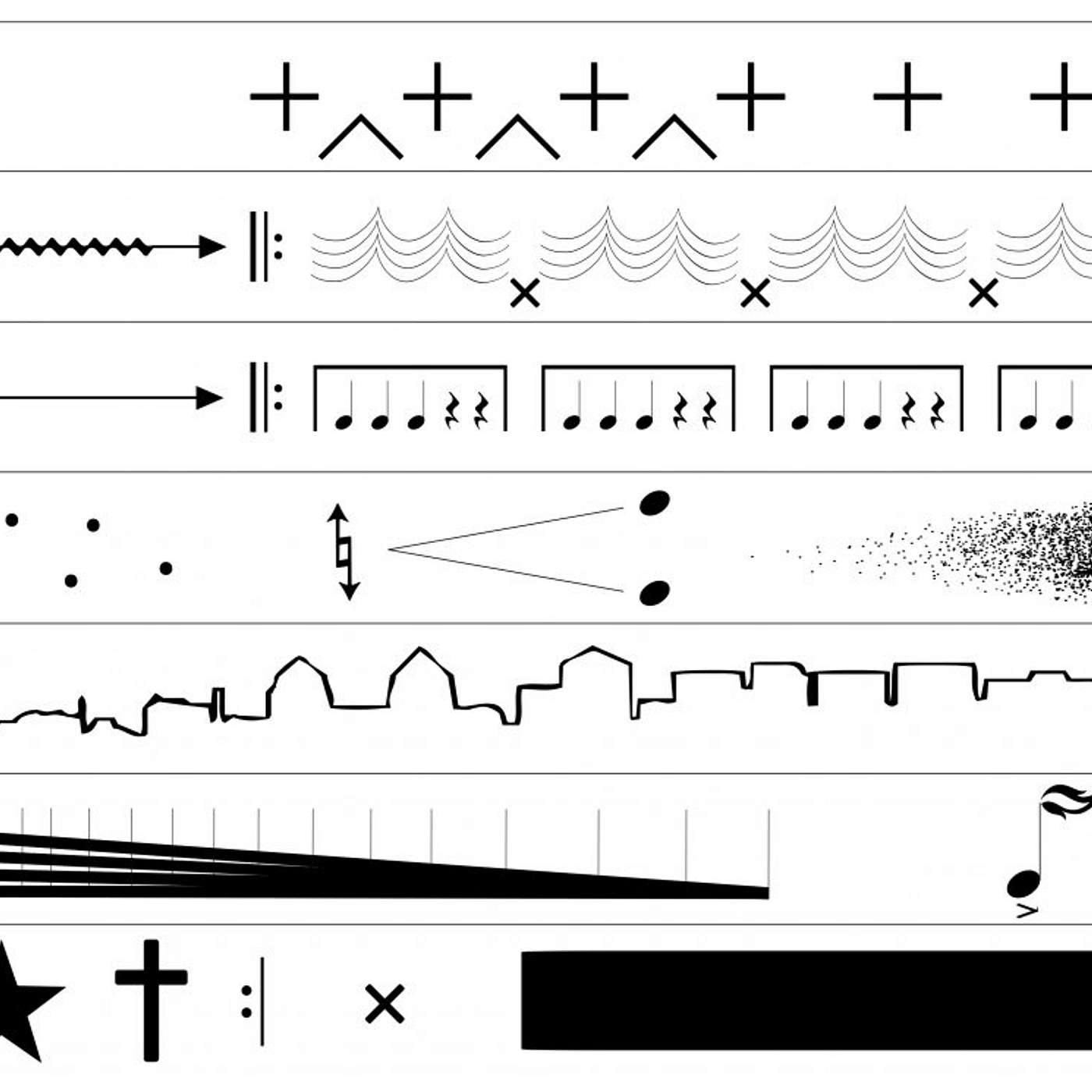

Raven Chacon:It doesn't make sense. And if that's the way to get music instruments into kids hands, so be it. But like, an example of one of the schools, there was a school, Monument Valley High School, and you look down the hallway, and all you see are headstocks of guitars sticking up, you know, every kid has a guitar, or, you know, a hand me down guitar or, or, like me, guitar with one string, boys and girls granted. It's just, it's just part of the culture there, you know, sometimes like a skateboard and a guitar, right. And, and so that doesn't mean that the students aren't interested in music, get those schools, maybe they're even more hungry, because they don't have that access. So in places like that, I have to show up. And my rule for this program is still, you have to write it in music notation, which might seem in a way hypocritical, since I do these graphics scores and text scores, but I still feel that that's the language, they need to meet the Quartet with halfway, you know, the ensemble who's coming all the way from New York to play their work, they should be able to speak at least that common denominator of language. So, you know, simplest kind of note, you can put a quarter note or a whole note, just kind of, you know, one tone, middle C maybe, and if nothing else, they write a piece for that. But I show them all the things they can do on it, you know, bend the notes, scrape the notes, scrape the violin, bow it fast. And a lot of these techniques translate from guitar Anyway, you know, fast picking, triple picking, whatever, it's the same kind of application on the on the other strings. So. So that's, that's been the work. Yeah. And the next, the next project for that is hopefully to, to build an archive of all the recordings of these pieces. I mean, by it. I've, I believe I've helped make 300 or more compositions come into being between Mike and I teaching these kids. So yeah, probably about 200 students we've taught since 2004.

Matthew Fluharty:And are there outlets where folks can hear some of these compositions right now,

Raven Chacon:there is, you know, Performance Today on NPR, did do a couple of episodes or programs on on this project. So I believe they still have some active web links. If you go to my website, I have a link to one of those where you can, you can hear and see video of these performances at the Grand Canyon. But yeah, keep an eye keep an eye out, maybe through my site. That's, that's my next project is to try to try to build a dedicated site for all of the work that these students do, and try to archive all of the scores and audio files from from these pieces.

Matthew Fluharty:Then what we can do for folks who are listening to this podcast, please check out the show notes where we'll link to the performance today piece the raven has mentioned alongside what he has on his website about the program. You know, Raven, speaking of show notes, and links to current and evolving work. I wonder if maybe that's a bridge to your most recent release in anthology of chance operations, which I think maybe has, at this point, been on for maybe two or three months and has really has been released, very wide critical acclaim. Would you be able to share a little bit about how this LP came together and some of the work that's featured on it?

Raven Chacon:Yeah, the well Ongoing is, for me is any opportunity to record. And while a lot of that is solo, a great deal of it is with collaborators. And so over the past 20 years, I probably do work on maybe three or four, maybe more recordings a year. And a lot of times those might end up as content for an installation or a video piece I'm working on, or something else, but it all kind of just ends up in a, you know, in a folder on the on the desktop, or whatever. And this kind of compilation of recordings and, and different, some of them coming from different experiments I've done, some of them coming maybe from an instrument I've built or tried to build. A lot of it is filled recordings, you know, any combination of things I just tried to try to document making sound. And so this, this most recent album I put out, was actually the first album, my solo album I'd put out in 10 years, I hadn't released anything, just under my name, things that considered solo work in in 10 years, since 2010. And what it what it was was was just this random assortment of different experiments I was doing. Some of them were documentation of sound installations. So the one singing toward the wind now singing toward the sun now that that was actually a sound installation that was installed at Canyon De Chelly, just outsid of Chinle. And was documenti g this these kind of wind har s and solar powered instrumen s that were put up out ther Another piece, I think it's called to Yoni and that's the name for for this place in northern New Mexico, which also is called Bandelier National Monument. And it sees runes, very ancient Runes of indigenous people who are the ancestors to Pueblo and other other tribes. And my wife and I went to go visit this site, I'd been there many times, but we went a few years ago and walking and being very quiet, actually just kind of listening. But we went into a few rooms, and we were talking to each other and walking around, and they were really struck by the resonance of this of these, you know, stone, stone structures. And so I captured some of that, that resonance just on my phone, actually, and went back in a studio and just listened to the profile of that resonance, and tried to incorporate that into into a recording or other experiments or trying to actually transpose that resonance on to other instruments. There's a song there's a Yeah, call these songs actually. I'd like to think about like that. They're very short, you know, too, and, and a lot of them function like songs on an album. I don't, I'm not gonna call them compositions or anything like that, because I don't feel like composed all of them either. But there's one called m v h. s. And what that stands for is what I was just speaking about a few minutes ago, Monument Valley High School, are all the kids have these guitars. And there's they did have a really good music teacher A while back, who was I don't know if this was his curriculum or curriculum of maybe the school district but they had a class where the young kids had to play the five hole, quote unquote native american flute kind of pentatonic scale. I don't know where the flutes came from I imagine maybe they were possibly bought off Amazon or the school supply house. They probably weren't wooden either will be they're probably plastic, but it's it's filled recording while I was there teaching kids in the other room how to write string quartets, I heard this amazing sound of 20 Navajo kids trying to play what this flute manufacturer believed his native American music, and it's never going to learn No, it's never going to be in tune. And because this is a beginning music class, and the students don't quite have the experience of playing as an ensemble that it was never going to line up. So you hear all of this really beautiful misalignment, of trying to replicate the sound of what this flute believes it's representing. There's a collaboration called msrc, which stands for Marc Sabat and Raven Chacon. And that's myself and composer Marc abat playing on a custom built rgan. That's what I'm playing. nd he is playing a modified iola, which is set to a pecific tuning system that that ark had developed. So we are ot playing the typical diatonic nd chromatic pitches that are ound in western Western onality or what they call an qual temperament. But now we're laying these kind of microtonal itches and and improvising with hose two instruments. Which is, hich is the only collaboration n the on the album. There's also another one, it's a study, it's called study for handmade bird calls, and microphones sticking out the window. So that's a recording I like to make. And I've done it many times to create drones is just drive around and stick a microphone out the window. And I speed up and I slow down. And like to believe that that affects time and pitch, and volume. And I have a lot of these recordings. But I also like to then try to superimpose other kinds of things on to them. So I've also been interested lately in in bird calls, you know, the weather, whether they're wind, you know, small wind kind of flute, or whistles or more kind of friction instruments. The Audubon Society actually sells these really beautiful little twisted, twisted toys. I don't know I don't know how to describe it. It's a piece of wood which has a little piece of metal inside of it. And you can twist it like like a knob, and it chirps. And so I like to put these together either on site or in the studio and kind of see what how they interact, you know, what, what cuts through the other, you know, what kinds of harmonic content comes out on top of each other. So that Yeah, some of these are just merely experiments that ended up on this on this recording.

Matthew Fluharty:Raven, thank you for that. And thank you for sharing the selections, we've also been listening to a phrase you use that I wonder if you could return to for just a moment is this notion of beautiful misalignment. And I'm interested in how that the sort of the action and the energy of that, in contrast to this notion of equal temperament, which is a term I'd never, never heard before, and I don't know the definition, but I feel like I, I can feel it can feel a definition, there's somewhere, you know, and it, it for me, like it opens up a space that I feel like a lot of a lot of your work has opened up in my own experience of which is this questioning of what field recording is like, what it is historically, what it has been the way that it to them to use something out of the musical lexicon to say that it is the way it has been pitched towards communities and away from communities, the way that it's, you know, I think about my, my own orientation to the word is super heavy, I mean, feel recordings for me is like a, it's a real shock. And like, Alan Lomax, his face appears out of the ink, you know, like, there's that tradition within that word. And, and thinking about this notion of beautiful misalignment, and in the creative practice that, that you've shared across these pieces, I'm struck so deeply, by the way, that your work is challenging all of us to ask questions around the kinds of categorization and extraction and almost like academic distance that has been inside of us notions of field recordings, and like that form has been critiqued before, you know, that is a long, productive, long standing critique of a lot of the politics and ideologies within this work. My experience of these pieces is that there's a resistance to what a times can be a really restrictive linear, almost like dual kind of subject object relationship between listening and the act of being on land and in place,

Raven Chacon:I can probably trace back my interest in this field recording practice to, to just the first the experimentation of using cassette tapes to make music and trying to document things like, like, we were saying, you know, the, the band playing in the desert or in the basement or whatever, you just try to make recordings. And for me, fidelity was always, you know, an obstacle like, like many people who are trying to understand recording, but it was something I embraced early on and, and thought it might contribute even to the to the sonority of whatever I was trying to capture in some instances. And then I was I was doing other kinds of projects, like the very first piece I claim as asset work as a piece I made in 1999, called field recordings, where I was wanting to record the quietest places I knew. So again, back, I went back to Canyon De Chelly, I went to Window Rock, Arizona, I went to some places, I would hike in New Mexico, Sandia Mountains, and just try to capture these places on on quiet days. And I was really interested to see what would what I would capture. And of course, because I went on such quiet days and made it and recorded it in such a quiet environment, under quiet conditions, I wasn't hearing anything. So I kept turning them up all the way to their maximum and, and then I could hear the magnification of what I was hearing. And that became interesting, I could hear these different kind of colors, if you will, of what these places were. And I realized maybe I was giving an opportunity for the land to then say what it had to say. And so fidelity has always gone out the window. You know, I it's not a concern of mine, really, and maybe it never was. And for me, there's still enough information about the context of the place. And maybe my hope is that there's there's information about the history of that place as well. Or at least there's an opportunity to consider that, you know, what that place is if that if you're hearing that place amplified to its maximum, maybe your maybe your your ear has brought you to to be attentive to, to what else is happening there, or that just that the place exists in the first place. But But my reasons for making full recordings surely are in contrast to any kind of an logical OR ethno musicological purposes, at the end of the day they are to make music and maybe or maybe to analyze in a way for myself to make other kinds of music. But they're not necessarily there to document pristine nature. The more more recent project I did around, I guess, so called field recordings would be the recordings I made at Standing Rock during the #DAPL Gathering. And that was that was a different kind of what I like to call deep listening, deep listening of emergency where I had the recorder on me the whole time. And there was so much happening, even sonically in retrospect, that it you try to think well, what was the speed of this place? What was what was the who were who were the people on the recording? Who was there? Who is in the encampment who was yelling over the hill on loudspeakers and l rads at the water protectors? Was there rest was there. I mean, I tried not to capture any praying or even singing, there was a lot of beautiful singing, but I wasn't I wasn't interested in in that I'm not a documentary filmmaker or anything like that. It was more just to maybe to think about land and and density and and time.

Matthew Fluharty:I'm really struck in how you've written about that, that period, that you were there in the LRADs were there. And I feel like I even kind of in perfectly understand what those are. But for folks who might be in the audience, Raven, can you share with us what an L read is and how it how it functioned in that environment?

Raven Chacon:Yeah, an LRAD is a long range acoustic device. And it's basically a sonic weapon. I believe it was developed, maybe around 2008 2009, I might be wrong. But it was first developed on cargo ships off the coast of Africa to supposedly warn pirates to, you know, to get get away, or they will shoot. They've been justified as having usage for warning communities of tornadoes or hurricanes. But from what we've seen, they really just get used as, as dispersal or even torture kinds of sound devices, where we're, they're extremely loud, extremely piercing, there's actually a button on there, that is a siren, that can be used. And they're very directional, so they can aim it at a, you know, small crowd and get them to, to disperse, you know, from wherever they're, they're positioned. And I don't know what else they've used them for. There's there's probably many things that have happened that we're not aware of, yeah, with their usage. But they were used at Standing Rock, you can see quite a, quite a few of the photos from near the end of that, that standoff of them using it on water protectors who are positioned up on a hill. And of course, they're probably saying this was the way to reach them over a long distance. But as we do know, that can inflict pain, and even, you know, hearing damage and other kind of probably psychological and physiological damage on on to people.

Matthew Fluharty:And then in one of your collaborations with post commodity, the L rad makes an appearance. In the years between worlds, we're always speaking in the spatial context in which the rat appears is in Aristotle's Lyceum.

Raven Chacon:Yeah, part of the reason I went to Standing Rock not only to go as an indigenous person in the United States to see what was happening and to support the water protectors was that I did hear that these were making an appearance there in North Dakota and being used on people. And so at the same time, I was doing research around these weapons use Sonic weapons because we were planning to use them in a in a sound installation, and I thought it would only be fair if that I experienced one firsthand and I guess fortunately I never, never did. But we did end up purchasing two of these LRADs post commodity funny enough or maybe not funny. They they were available on eBay. Oh my god, I forgot what we got what you so they aren't. They are technically I guess, are legally not considered a weapon because they have these other kinds of communication capabilities. But we were able to obtain two of them and ship them to Athens, Greece. Now the the art piece is what we like to call a an all day. Music Composition. I think it lasted 12 hours every day and consisted of two of these all rads on top of buildings that surround Aristotle's Lyceum. These two buildings are the Athens Conservatory of Music and the Hellenic Armed Forces officers Club, which kind of where the police and the military personnel go and have banquets. And what is situated right in the middle is the place where Aristotle and his students would gather and walk around amongst the grounds around the grounds and, and conduct the lessons that they were they were having. So they wouldn't sit and have their lessons they would actually, you know, walk on the earth. And part of this this philosophy of peripatetic, learning that as they're in motion, as they're stepping on the ground was a more productive way to learn and to teach. And so what's coming out of these LRADs? Mind you they're not they're not emitting loud sounds as intended by the LRADs but we turn them all the way down to their minimum is narratives that we gathered, I guess, I guess, more kind of filled recordings, if you will, Cristobal Martinez gathered some some stories from folks who had arrived in the united in the United States from traversing the US Mexico border lands, speaking about their experience of walking through the desert, for a better life here in the United States. Meanwhile, I was in Athens, Greece, interviewing folks who had crossed the Mediterranean from Syria, Afghanistan, Africa, and have arrived in Greece to await their seeking of refuge in the European Union. And we also gathered some narratives from the Cherokee Trail of Tears, and other instance of forced migration. And the Navajo long walk, where Kit Carson forced my tribe to traverse the desert and be relocated in this concentration camp in the middle of New Mexico in the 1800s. And so combining all of these narratives, we wanted to set that against the grounds of peripatetic learning, and thinking about walking, moving, learning, and teaching. And so that piece was up for 100 days at documenta 14. And it was our It was our way to subvert the usage of those of those l rats.

Matthew Fluharty:How was this piece received by folks in the city? And then what was the response like? Well,

Raven Chacon:there was some early hesitation and pushback in that there is a committee there in Greece and in Athens, who are there to protect, you know, their sacred sites of Greece, of course, we acknowledge that the site of Aristotle must be equivalent to the sites that we hold sacred in the southwest, you know, our own indigenous sites. But at the same time, we didn't install anything in the Lyceum. We were sending beams of sound into the Lyceum. And we wanted, we explained, we wanted to have this this dialogue of Greece's position in this mass migration, and asked this committee to, to allow us to respond to that and to be a part of that collaboration of response. And so eventually, they they let us do the work as far as other other audiences, they're both local and visiting documenta. It was, it was received very well, I think it was a bit hidden too many folks too, who weren't aware that it was going to be there because it's purely a sound piece. I mean, other than the LRADs, which are on the adjacent buildings, one didn't, maybe didn't know that they were going to be hearing, you know, these narratives. There was also a lot of collaboration with musicians in Greece while I was there, I was there for four months. And while I'm talking about these, maybe these narratives from the Americas they were we're How do I say this? Maybe Maybe there was a cross collaboration in our composition, where, for instance, the Cherokee Trail of Tears narrative was translated into Greek and was spoken and sung by a Greek musician. So we were we were combining narratives. We were overlapping narratives. We were making this kind of cross musical narrative happen. We also I think we composed like ranchera In using lute and Greek instruments, and also there was another piece that that use different languages Arabic, Sami, Sami language and one it was it was it was not a it was not a direct and literal telling of individual stories all the time, he was speaking about it more as a shared experience between a lot of different people who are in these situations of forced migration both in the past and currently.

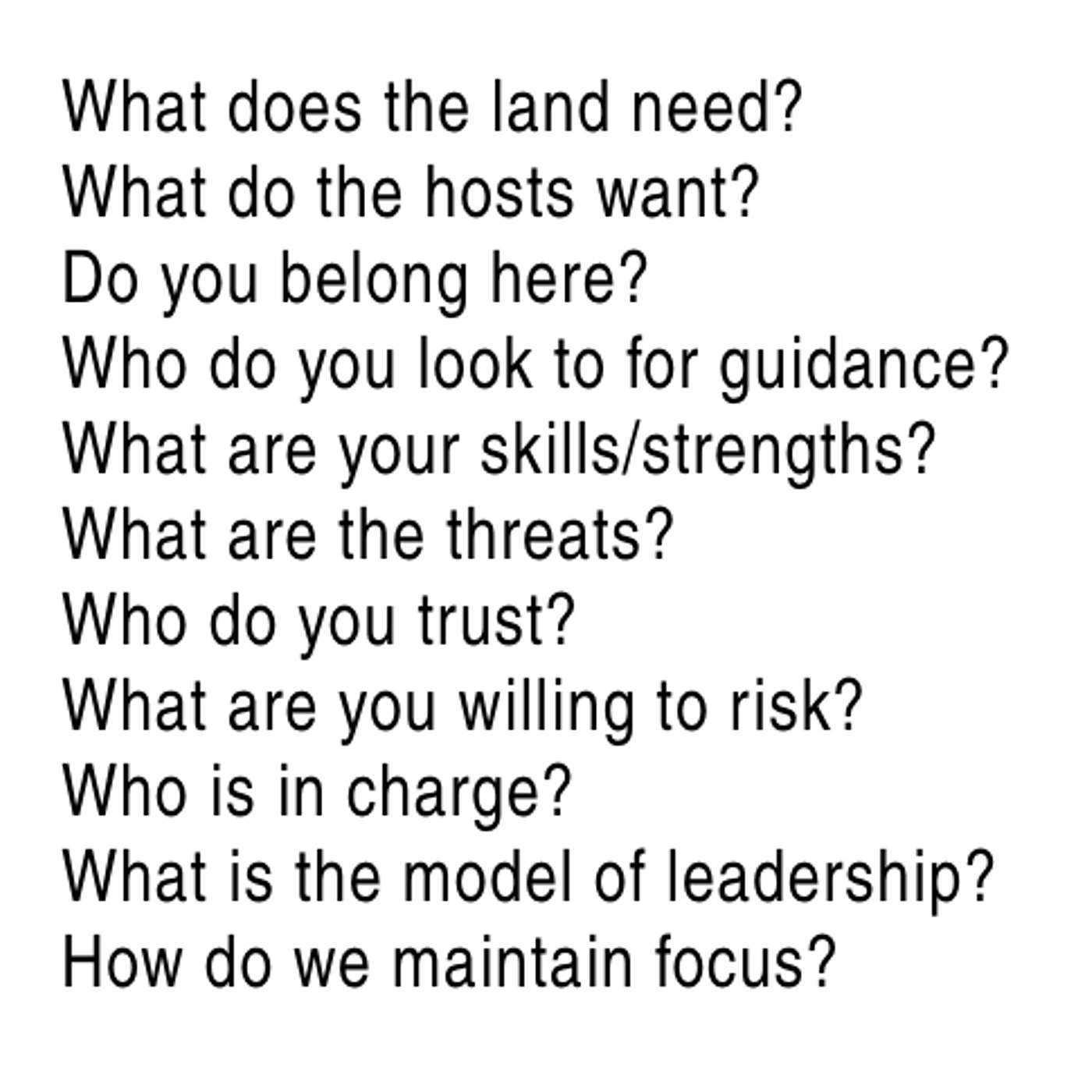

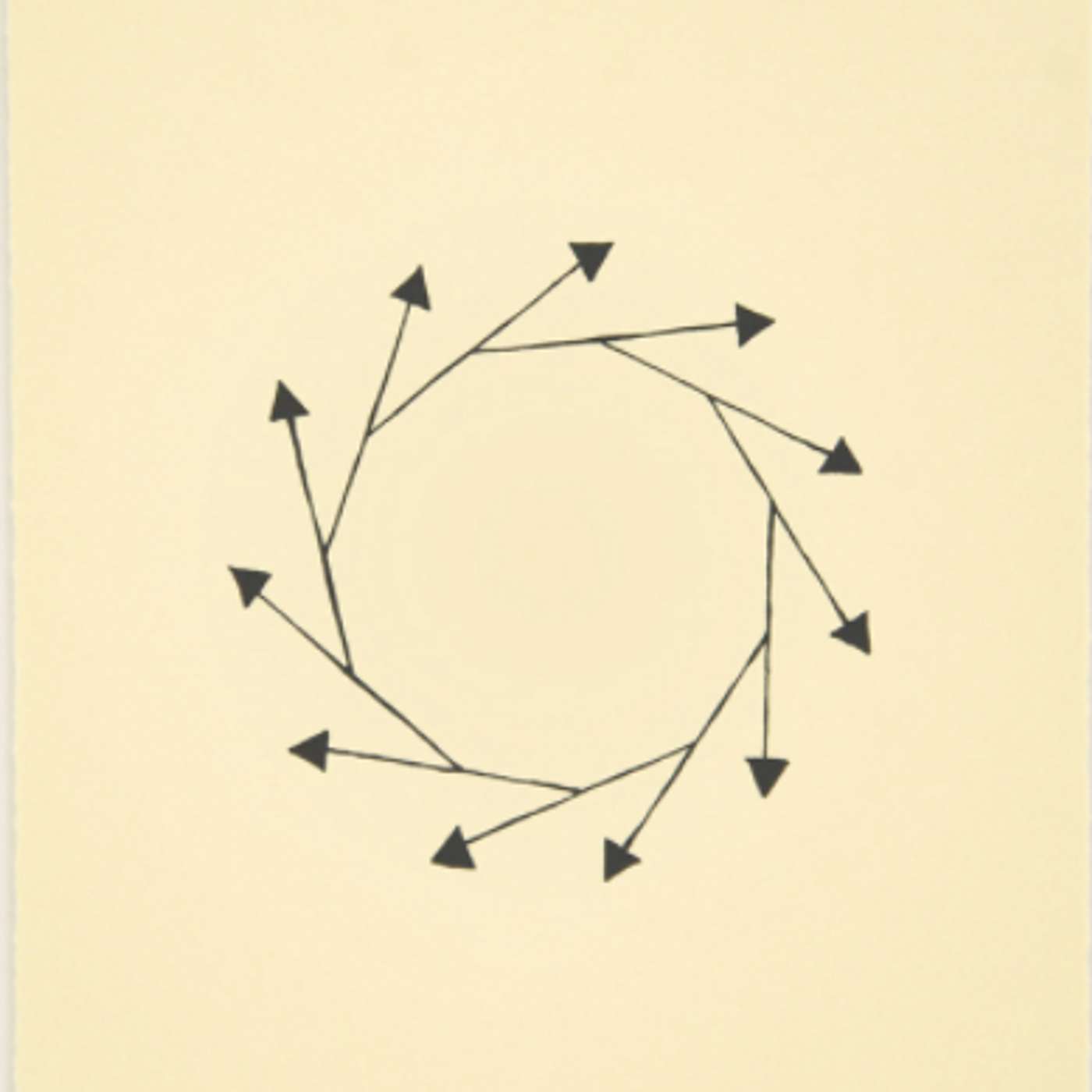

Matthew Fluharty:As I think about what you've just shared about that experience in Greece, and I think these questions are on asking, what's, what one's position is, it leads me to dispatch a piece, which is a collaboration between yourself and Candice Hopkins piece, which it sounds like is, is evolving, has been articulated and is evolving. And I thought maybe as a way in into sort of talking about this work and, and thinking about American Ledger, if I could just share the preface that you wrote in November of 2022 dispatch. You write "Dispatch is either a transcription of events around the 2016 dapple encroachment at Standing Rock, a prompt for an ecological oral future, or at the very least, a critique of the privilege of meditative deep listening. This score can be realized as a performance or as a series of imagined events. It can also be enacted in the real world. The players the prompts in the schematics are derived from an analysis of the surface dynamics and organization of the water protectors in defense of Standing Rock during the no dapple movement, not glossing over the miscommunication, profiteering and injustices in an increasingly fractured society, new paths and new formations are needed to refocus our attention in an attempt to find truth. Participating in the score may produce Sonic or visual artifacts. These are as important as the actions."

Raven Chacon:Yeah, so we well, that piece that started back to this, what I was mentioning earlier, this this time that I spent at Standing Rock. And I do want to say I was invited to, to be there by Cannupa Hanska Luger another native artist, is kind of been involved in other collaborations also that that I've been involved in recently, mostly the sweet land opera, but he's also doing a fantastic project called Settlement. That that is ongoing, also ongoing kind of web web site and collaborative project. But when I was up there, and as I was saying, I was making kind of filled recordings and thinking about just the diversity of folks that were they're gathering to, to mostly support this project. I was I was blown away by by the complexity of have that have that experience and that, that gathering that that was there upon the land, one of the other things that drove me to going in the first place to I mean, I mentioned the El rads and, and what I felt was my responsibility to go was also just trying to untangle all of the noise that I was hearing at that time about what was taking place. I mean, I, I felt at the time that there was a lot of misinformation or rumor or, or just fabricated stories coming out of there. And I couldn't tell if that was coming from water protectors, if that was maybe what's what's more apparent these days, these kind of trolls like these imposters on the internet saying, Oh, you know, we're hearing story reports of this and that and people getting their arms blown off, the cops are coming in shooting at people. So I really wanted to go for myself and see what was going on. I was getting, I wasn't satisfied with social media being my only news source for for this important event. And so, I think, stemming from that, this, this idea that, that communication, that news, that knowledge that a message was not quite getting from point A to point B point A. We think of being of those being the hosts, the stewards of that land, we're Standing Rock is but also maybe let point A being the land itself Having a message, a cry, that needs to get to point B, whether that's other native people, whether that's everyone who feels obligated to, to protect the land, I felt it wasn't, it wasn't so direct. And definitely when I arrived, I saw that it was even more entangled. It was more diluted, it was more noisy. And it was, it was far more complicated than I then I understood. And so the filled recordings after helped me kind of just listen and try to analyze what was happening. Again, listening to the dynamics of the place. Listening to I don't want to use Word characters, but let's say listening to the ensemble of who is there. And it got me thinking, of trying to put this in some kind of score are not quite a score, not quite a prescription, or an instructional score, maybe maybe serving as both a transcription and an opportunity to create new prompts. So as I was sharing this with Candace, we started thinking, Well, you know, she wasn't there. But I was telling her Yeah, there was, there were water protectors, there were a variety of folks coming from, you know, native folks coming from other reservations coming from urban places that were of course, the host Lakota people who were letting us be there. And there were journalists reporters, there were undercover cops. I mean, there was everybody there was like Burning Man, people wanted to come just hang out. And, and I was wondering how all of this was contributing to, to what the elders there at Standing Rock, and an importantly, what the land wanted. And as direct action was happening, as people were actually trying to go and maybe prevent the bulldozers or the tractors from digging out the land there, but all of a sudden bees, you know, somebody would say, No, stop, you know, the elders don't want to do this right now. Or, you know, somebody said this or that. And I was realizing there was still noise and miscommunications and, and other kinds of steering of sound, and messaging that was happening there at the camp. So I started to think, Okay, well, let's try to analyze this, let's turn it into some kind of maybe even like speculative fiction, like saying, well, doesn't have to be Standing Rock, these things are ongoing all over the world. Yeah, every month, even we hear of a tree in Australia, that's gonna get cut down because of highway or another pipeline in Canada or elsewhere, you know, encroaching upon an indigenous community. And the score dispatch is an opportunity to start thinking about who would show up what they might do in these places, how they can assist in creating some kind of carrying of knowledge of knowledge and message. What are the tactics in amplifying that message, amplifying might be the wrong word. Because amplifying is actually just one of the tactics, I mean, you can, you can relay a message, you can say the message for a long time, you can come together as a chorus and double up that message, you can change the register of that message. By by that I mean something like, a man might be saying something but then it's when a woman says it, maybe it means something else. Or maybe when a young person says what an elder saying maybe that reaches a different audience, and vice versa, of course, trying to think of you know, how sound, the parameters of sound, can be utilized to, to carry a message is really the point of the score. And they they become propositions to consider but also I would try to think of maybe there's a way to enact these in real world scenarios to so we're not really necessarily coming up with a manual for for her activism or protest at all, but really just trying to analyze all of the all of the dynamics and players involved in these situations. And that's that's where it exists now as a score. But the next step is a collaboration with chalupas settlement project in having artists maybe analyze their own situations that they're involved in, or, or create creative applications or reenactments of the prompts in the score.

Matthew Fluharty:You know it, something that struck me about this piece that I'm really grateful to have heard more just through through what you've shared, is this notion that within all of that is also a critique of the privilege of meditative deep listening. I'm interested to hear what what that means right now, for you how that that landed with me speaking from, from my cultural background as a European descended person, one can say that they're entering an act of listening or even, quote, unquote, deep listening, if we're I mean, that that is its own kind of a status sized sort of reaction to a set of conditions. But every celebrity Corporation entity in the last year that has realized air has said that they're going through a process of deep listening or listening, it doesn't signal the stakes of the deeper conversation you're suggesting, in dispatch, you know, the culturally like we're living in a moment where the act of listening itself ought perhaps to be critiqued in these ways.

Raven Chacon:Yeah, yeah. It would it doesn't signal is the next action, right, and, and direct action in saying, well, we should find out what exactly is happening, we should try to spread the message and bring attention to what is happening at this, let's say this site of conflict and not succumb to hyperbole or, you know, even, you know, these kind of emotive exaggerations, that Yeah, of course, everybody is angry at this encroachment. But at the same time, there's an obligation to try to explain and try to share what is truly happening at the site, you know, if there truly is an injustice happening, I think the best we can do is, is be truthful, about about that message and about that, you know, narrative that's happening. Otherwise, it turns into some kind of thing that's happened in more recent times of this, you know, so called fake news or whatever. And this kind of, you know, everybody the having these conspiracy theories about around what's happening, and that is surely not going to work in our favor for those of us who are trying to protect the land and protect indigenous rights. So this deep listening back to this kind of that idea of thinking that you are aligning with the concerns of the land and the hosts. And really, you're just taking with your ears, you know, you're seeking your own resolve in this place, and you go and visit it, and then you go and drive back to LA or whatever you go, you go out to the desert, and meditate, do whatever. And when really, there's more things that can be done. And when you do find yourself in those direct action situations, you will find that it's not a meditative place, you're really having to, to listen out for drones and l rads, and the police collaborating with the private pipeline security to come raise your camp. And so that was that was a bit of what we were talking about there is is what is truly is the sound of the land that has been under attack.

Matthew Fluharty:Raven, I'm grateful for your time. And it's been really exciting. Just Just to have this conversation about the arc, the wide arc of your work over these years. And just in what you've just shared with dispatch, I'm wondering if that is a bridge toward American ledger number two, which is a piece that is currently on view at the Plains Art Museum as part of the high visibility exhibition. So I'm curious about maybe first about how, how the American ledger series came about, you know, what, what the story of its beginnings were, and maybe maybe in particular, how American ledger number two came together. And in collaboration with folks in Tulsa,

Raven Chacon:the American ledger series started as a well, it really started years ago, when I was still a member of post commodity. We're working on a large graphic score that was going to be made of the elements found in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, from a furnace that was no longer in use. And that piece was to tell the history of that place, through its materials and hopefully through some kind of form. And I had wanted to make an subversion of the American flag with that with those materials, and that didn't end up happening for that piece. That's okay. I used it for American Ledger No. 1 which was commissioned for a different exhibition. And that piece came together because of my interest in maybe maybe my interest in not having a score for performance in the traditional sense. So usually there's a master score that can align everybody involved in the composition. And then individual musicians might have their own part, or it might follow the score to play together. And they wanted everybody to look at just one score. And that one score, then wouldn't be a big sheet of paper, it might be something else, it might take the form of a wall, or a door, or a billboard, or a flag. And the score itself would be this subversion of the American flag. So it has these kind of already you already, when you look at the American flag, you already kind of look at it from left to right, as if it's a written page, maybe, or you know, how we read music notation already has these kind of bars, which could be staff, music staff, it already has dots on there, all the stars are some kind of pointillistic thing, that's how I look at these objects, like they could potentially be a score so so I thought if it was already doing that, then maybe there's a way to make it tell the story of the United States. And that's what that piece became American ledger. One tells the story from left to right from top to bottom, the events of of American history, from contact time to settlements being built to slavery being carried out through the genocide of indigenous people, and all the way through, you know, the civil rights, movement, assassinations of those in the civil rights movement, and all the way up until the unknown future. And so, after that piece, there was a clip, there's a collective in Oklahoma, we're originally from New Mexico, actually, called Atomic Culture. And they commissioned number two, and they were seeking a, a site specific work for Tulsa, Oklahoma. And so I continued the series, and made a score. That's a some version of the oklahoma state flag. And so things like circles, and I don't know there's a feather in that flag, those can become other kinds of musical shapes or extra musical shapes or indications they can become arrows, they can become railroad tracks, they can become, I don't know, a megaphone trumpet, it can become a fermata, or crescendo notation, I start kind of piecing these things back together the elements of the flag, at the same time thinking about the place I'm writing about. So what American ledger to is, is that one is asked to be presented as a billboard. I think as any railroad debris, or as any burned, or paragraph object. So in the case of how was presented at the Plains Art Museum, it was a plank of wood that was burned, where the score was burned into it. And this score is a little bit different. I would say it's not exactly the same kind of theater performance piece that number one is, this one speaks to forced migrations into and out of Oklahoma. So I was talking about the forced migration of tribes being relocated from elsewhere in the United States into Oklahoma, and forced to live in that area. Also, there is a host, there are host tribes in Oklahoma, who were also, you know, a bit displaced by this forced migration of other tribes. And as cities were being built, there was also you know, black communities starting to a forum and because in these places, and in the case of Tulsa, a quite successful community of black folks who are starting their own businesses or own banks or own newspapers, which then led to an incident called the, the Tulsa massacre. And therefore then, this this community then having to retreat, or dissolve its own community because of that, and what the piece, then the way the piece gets performed is using two drums in the shape of a circle. So there's a number of players who are kind of walking a ring around to drums and every player Has is carrying either three drum sticks, or three match sticks. The idea is that they can hit the drum. If they're carrying a drum stick, and once they hit that drum, they must give their drum stick to the person behind them. When they are not carrying a drum stick, they can light a matchstick. And so people are either hitting drums or they're lighting matches. And walking as if they're kind of carrying this candle, if you will. And it's a bit it becomes a bit of a hot potato dynamic in that, you to to, to get out of the ring of performance to let's say exit from the performance, you must absolve yourself of these, these drumsticks and matches. So you are constantly trying to contribute to the to the collaboration to the walking ring. But you're also trying to get out of the situation. And so people end up with too many drumsticks or people end up in a situation where they cannot hit a drum. And it's this kind of negotiation of trying to balance equity, of allowing everybody to be able to speak to contribute. But also, nobody wants to be in this in this situation, because eventually you're going to get stuck with all of the drumsticks or all of the matchsticks there's also a burden as you as you exit the piece, you play a melody on a marimba that's situated in the center of the ring. And as you exit, you must continue this melody that's being played by the people who have exited previous to you. So that's another reason to exit the piece early is because you will have to have memorized all of the melodies, previous to you exiting. So what I wanted to do is try to replicate this, this imbalance. And this this almost crab in a bucket kind of situation that that the peace puts its participants into. But at the same time, everybody is trying to assist each other as well, working their way through the competition. And that's what the piece is it took more interest in the dynamics of the players, and what that might say about the history of Tulsa, and and today how communities might be struggling to collaborate. But but at the same time, there's limited resources to end in equities in these places.

Matthew Fluharty:You know, and perhaps this takes us back to one of the elements at the start of our conversation. Because I remember when we were talking about this piece for high visibility, I think it was maybe we were in the early stages of the pandemic. It was slightly unclear but I remember you suggesting that it is a piece that could take shape through a High School Marching Band, I remember you I remember you sharing that has that happened yet has a high school marching band. I'm trying to find the right verb for what that would be I mean to to be within that space to perform it.

Raven Chacon:Yeah, I Not that I'm aware of. As of this moment, there's only been one performance and that was the one organized by atomic culture for the very first presentation and hopefully when COVID ease is up plains will be able to do a version and I would love for for high school ensemble or marching band to do the project. A lot of my scores allow for let's say non musicians or people who don't have Western music experience to perform them. So anybody could really you know, perform this piece and I didn't want to make it inaccessible by having it be notated to strictly in any kind of, you know, Western music style or require any in strument virtuosity.

Matthew Fluharty:Raven, I'm so grateful for your time we're about at the end of our window together in our conversation, and I really just have two more questions as we sort of lead out into our respective days. today. What are you working on? You're excited about in 2021? Are there other projects ahead that are really stimulating you right now?

Raven Chacon:Yeah, yeah, I mean, I I just completed a series of graphic scores one page graphic scores with Crow's Shadow printmaking studio in Eastern Oregon. And those are maybe what can be described as portraitures, 30 dedications to contemporary Indigenous women, sound artists and sound scholars and musicians who are making interesting work today and who I am a fan of each of these 13 musicians. And so that recently was, was premiered all 13 at Crow's Shadow, they're available now. And I'm working on a book that further elaborates on on the project and, and what the scores mean. And beyond that, I recently got a camera, video camera and doing more and more video projects. That's, that was, as always been an interest of mine and a medium I've worked in a bit with post commodity and other projects. And it seems with you know, with, with the zoom kind of era that we're in, that seems to be the best way for now to, to share music, you know, to share with a live performance or a music presentation. So I decided to upgrade my skills and gear and work with that. So I'm looking forward to doing more pieces with that. Maybe more kind of filmmaking projects.

Matthew Fluharty:We could really use all of your genius to help us reconceptualize our relationship to zoom and electronic media. And this moment,

Raven Chacon:I'm still learning zoom, I didn't I don't even know half the things that I think one supposed to know about it. Well,

Matthew Fluharty:We're counting on you, Raven. You know, in before, before we, before we head out here this afternoon. Just one final question on the we the we ask all the folks who stopped by for these conversations, which is, you know, what, what is moving you right now? You know, what books, music, art, food, places, traditions, ideas, I feel exciting and relevant and feel like they have a presence right now. For you.

Raven Chacon:Wow, I have. That's a hard one. I feel like a lot of people probably right now very isolated. You know, I haven't I haven't really been traveling or anything. And I feel like maybe that's a good thing. I feel more connected to where I live, where I try to live Albuquerque New Mexico than then I have in a long time. And I think it's because I've been home and I haven't been traveling. And I've been able to, you know, spend time in my own house for a change and try to visit with friends in the area. But yeah, it's given me a different relationship of how I intake something like music, you know, I'm listening to a lot more radio online radio, starting a radio project here at CCA Wattis here in San Francisco. Just trying to consume as much as I can, through through online sources, which which isn't ideal, but you know that that stuff is available and I feel there are some people taking advantage of being able to share in that way. Books, there was a there's a fantastic book that came out by sound scholar indigenous sound scholar Dylan Robinson called Hungry Listening, that I'm starting to read right now, in which he talks about the settler ear and maybe maybe this idea that we were talking about earlier in the, in the discussion today about what we might all take from listening or what we what we try to gather from listening and and reciprocate, you know, in in how we share sounds. That's something I'm starting to consider too as I do this work these works like dispatch and American ledger. And, and yeah, I think you know, of course, looking forward to two things getting back to so called normal.

Matthew Fluharty:Here here, you know, I have to ask Raven, is there a particular internet radio station that you would lead some of us to

Raven Chacon:you know, there's a lot of them out there, but I've been especially listening to one called Radio Alhara that's on line right now and is broadcasting out of Palestine. Beautiful.

Matthew Fluharty:Thank you. So for folks that are listening, all of these amazing suggestions. All of the links to the various works and performances that Raven has shared will be included in the show notes and online at in high visibility.org Raven, thank you so much for your time today. I'm grateful. Thank you. Thanks again to Raven zuccon for his time and generosity in this conversation. Please check out the show notes in the high visibility site and in high visibility.org for further information on all the work and ideas discussed. Please also check out planes Art Museum and planes are done. Or to learn more about the high visibility exhibition, which is on view in 2013. And thanks so much for spending some time with this conversation. Take care