ASH CLOUD

ASH CLOUD

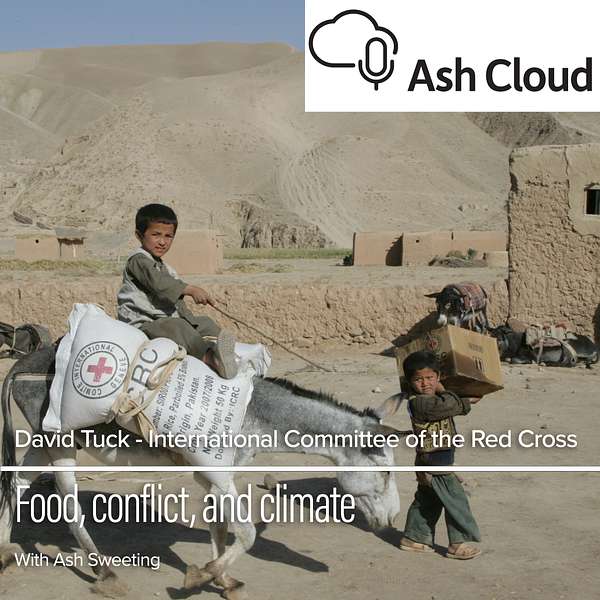

Conflict, climate change, and food insecurity with David Tuck International Committee of the Red Cross

Of the 25 countries that are least able to adapt to the impacts of climate change about 14 of those countries or 56% are currently affected by armed conflict.

The intersection of conflict and food insecurity is an area of series concern in many of the places where the International Committee of the Red Cross works. The 2023 global report of food crises reported that around 250 million people globally were food insecure and in need of urgent food assistance. This is the highest level in the seven year history of the report. There are currently 100 armed conflicts globally involving around 60 states and 100 or more non state groups. The number of armed conflicts has increased over recent decades. In 2022, 120 million people were pushed into food insecurity by conflict.

Frequently it is the most vulnerable, including women headed households, that suffer the most from conflict and climate related food insecurity. This is not helped by the continuing weaponization of food, such as the restrictions of Black Sea grain export during the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war and the sieges initiated by ISIS the recent Syria conflict.

David Tuck is the Head of Mission, Australia, for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). David has spent the last twenty years working as a legal advisor at the International Red Cross across Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. During this time, he has witnessed the impacts of conflict on civilian populations including how the combination of conflict, climate change, and food insecurity have a multiplying effect that further weakens the resilience of effected societies. I recently caught up with David to discuss his work. You can listen to the conversation here.

The ICRC was created in 1863 following the Battle of Solferino. The sole objective of the ICRC has been to ensure protection and assistance for the victims of armed conflict. The ICRC is mandated globally to ensure all side of armed convicts adhere to the Geneva Conventions.

Dave, thank you very much for joining me today.

Unknown 0:05

Yeah, can I ask thanks so much for having me on behalf of the International Committee of the Red Cross.

Unknown 0:10

hunger and food security are frequently associated with conflict. And in most cases, it's the civilian populations who are the most severely affected both by the conflict and by the subsequent hunger and food insecurity. Are there any experiences during the years you've worked with the International Committee of the Red Cross that you can share with us about what life is like facilitate civilians living under those circumstances?

Unknown 0:40

Yeah, thanks ash. I mean, this question or topic of the intersection really of conflict and food is food security or food insecurity as the case may be, is of utmost importance to us as a as a humanitarian organization, an area of serious concern in many of the places in which we work, and you'll very much be aware that the 2023 Global Report on food crises indicated that some 250 million people globally were food insecure and required urgent food assistance, or was particularly alarming I think about that number is that in the seven year history of the report, it was to date the highest number of people who are globally food insecure, and at exactly the same time and here the data I lean on is of our organization, the International Committee of the Red Cross, we would point to the fact that there are currently 100 armed conflicts globally, with some 60 states and 100 or more non state armed groups. And that number to the number of armed conflicts globally has been on the increase and certainly in the last in the last two decades. The implications for people coming to your question. I mean, evidently are extremely serious. I think at the most severe it's, it's because or risk of severe illness and death, which are of utmost concern to an organization like ours. It's not infrequent that we hear stories of people eating twice a day only sometimes once a day, in certain circumstances having to forego meals for the entire day, given the circumstances in in which they find themselves. Interestingly enough for me, I think the story is at the intersection of conflict and food security that had the most profound impact. Were those related to the circumstances in the Middle East, around about 2015 16 and 17. Where siege siege of urban areas in particular was was very commonly practiced. And many of us I think, can recall the examples of Aleppo Eastern otter MondayA for care fryer and other urban centers in Syria at that time, from which the stories of people being exposed to severe food insecurity were were dramatic and harrowing. The story is very much of the sort of hollow faces of children who were searching in the remnants of their urban environment for grass or herbs to eat by the side of the road such such such as was the situation at the time, people in absolute dire need of medical attention, precisely for the fact that they've not been able to consume anything of sufficient nutritional value, but we're unable even to access medical services. Such was the complete separation of their environment from the rest of the world. And I think many of those stories have really, really stuck with me for for many years, ever since. One of the main concerns I think that we have around the exposure to food insecurity in situations of conflict is precisely how people will have to take fairly extreme measures or adapt early harmful coping strategies to be able to put enough food on the table and to be able to survive and so people will cut back on a range of essential services everything from an including education which will be forgotten in favor of simply surviving day in day out. We know in a place like Syria that there's been a whole generation of young people who really missed out on on educational opportunities in South Sudan we have stories of people being forced by severe food insecurity to harvest early, so to harvest their crops before those crops are ready to be harvest. And that's a sort of dramatic step that they have to take to survive. And of course, that has then flow on long term implications in terms of their capacity to survive and overall crop production in the context in which in which they live. As an organization, I think we'd be quite keen to point out of course, that food insecurity in armed conflicts doesn't necessarily affect everyone in the same way. And there are various ways I think to dissect this part of the conversation. But in many places in which we work, we find in particular that women headed households, particularly subjects to subject to the risks associated with with the lack of food of, of adequate nutritional value, and in places like Syria over the years we've actually really made sure that our humanitarian interventions reach precisely that cohort of households who are subjected to these to these extremes. We know that people who are displaced, particularly at risk of the implications of food insecurity, not least of all people who are used to taking their food from the land or the crops on the land on which they live and sustaining themselves they find themselves in displacement, where they have much, much less access to food, and another category for want of a better way to describe it a persons about whom We're particularly concerned, people deprived of their liberty or detainees. We are mandated particularly in times of conflict to work for the benefit and to ensure humane treatment and conditions for people deprived of their liberty and certainly there are a category of people who are extremely vulnerable and very much subject to the whims of course of the detaining authority. They're totally dependent on what the detaining authority will authorize to enter detention facilities. So it has been a long term concern of ours that when the broader environment in which detainees find themselves is facing challenges related to for example, food insecurity, that often detainees will be the last people considered in terms of their immediate needs and as such, they're particularly vulnerable.

Unknown 6:33

Over the audio seems to have dropped out for a second Can you hear me?

Unknown 6:37

Oh, that's right. That's right. Yeah. Can you hear me now? Yeah. Good. So yeah, I'll leave that one there. I should pass back to you.

Unknown 6:46

Okay, no, so I can sort that out in the edit in terms of in terms of in these situations, how do you go about providing humanitarian and food assistance to people in these situations, given that it's the middle of a war zone?

Unknown 7:07

Yeah, because it's very good question. And there's a lot of different components to the answer. I mean, one of the things that we do fundamentally as an organization to secure access, which is key access, both both to places but also very much to people, is we speak with all sides and all parties involved and that's very core and central to the modus operandi of an organization like like the ICRC we're neutral, independent and impartial, which is a sort of enabler or facilitator for access to people in need. Key also in this discussion is proximity and proximity precisely to the people. For whom we work, which means that we would hopefully be consistently in a position where we're able to assess ourselves, the needs that individuals have, but not only that, also very much to follow up and that's part of the due diligence, I think of distributing or providing humanitarian aid in a modern professional manner consistent with, you know, the expectations of contemporary humanitarian action that we can then return to people who, to whom we have distributed humanitarian assistance and ensure that it reached the the intended destination on food insecurity. More broadly, though, I think it's probably key to sort of step back for a moment and point out that sometimes the humanitarian solution or response is not necessarily or not exclusively, the provision of material goods, commodities, you know, food itself, very often in some of these cases, at least, there are considered relation considerations related to protection, work access, and sometimes just humanitarian diplomacy to unblock some of the challenges to access to food, rather than substitute for the authorities by providing goods to people who are desperately in need. So there's a range or sort of palette of activities that ought to be undertaken sort of preventive end, and also very much in that really concrete humanitarian response.

Unknown 9:12

You mentioned early the earlier that both the number of people facing severe hunger and food insecurity as well as the number of armed conflicts going on currently in the world is the highest in recent decades. How do you think climate change is affecting this this both the food insecurity and the hunger as well as the the conflicts in the world?

Unknown 9:38

Yeah, Ash, good question. I mean, not least of all, just as it's currently the last day of cop 28. I think what we would find is that we could overlay a map of those countries or areas that are most affected. by conflict, that are most affected by food insecurity, and that at the same time, at least able to prevent the effects of climate change and adapt to those same effects. So I think we would see a very, very strong correlation or connection for many countries. between all three of those elements. I mean, you can see in the notre DOM gain adaptation index.

Unknown 10:24

To the implications of the consequences of climate change, about 1460 or so percent of those countries are currently affected by conflict. So there's clearly this strong connection between between those elements. That's that's evident. Climate change, and the climate shocks and weather patterns that come with it, I think are likely to have a range of dramatic implications for situations of conflict. Minh, first of course, is in terms of the implications for production, certain climates will have more trouble producing the goods or the producing the food required for survival. weather shocks can also have more narrow implications meaning to say, even consequences that one might reasonably otherwise will normally otherwise find in conflict like displacement and people displaced by a weather event are going to be in similar circumstances to those displaced by conflict in terms of access to food and food insecurity as as a general rule. I also think that overall from a sort of broad humanitarian perspective, the challenge when we bring these factors together, food insecurity, climate change, and conflict is that they all have this sort of cumulative effect, which is working to really reduce or weaken the resilience of people who are subject to these to these circumstances. So they have a sort of a multiplying effect or consequences on people who are subject to the worst of of conflict, climate change and food insecurity, jeopardizing the capacity ultimately, to to survive. In certain countries in which we work. I think we can already see the implications of climate and climate shocks for people in these circumstances. So just to give you one example, in Somalia, some of our rain fed harvest agricultural projects we've actually put on hold or suspended because we have so much trouble anticipating that there will be sufficient rain for any meaningful harvest in the foreseeable future. And we now revert to providing simply cash assistance to the same people who might be in need. And of course, cash assistance is a direct humanitarian response. It has lots of Advent advantages, but it's not likely to be putting the people in need in a position where they will be able to sustain themselves in the future. So it's such a huge worry that we've we've had to turn to this sort of response just given the the climatic situation that we're witnessing in a place like Somalia currently. I think we would also add that one of the challenges that's been identified in relation to these contexts that are most hard pressed to adapt to the consequences of climate change, is that broadly speaking, there seems to be a lack of access for many of those countries to the climate mitigation and adaptation funding that is otherwise available. In the current and global environment. And that's because many of these countries affected by conflict are less stable, have less strong governance structures are possibly less able to demonstrate that they're able to kind of meaningfully implement climate risk mitigation adaptation projects. And as such, they're often less eligible for the funding or the money that is otherwise available to adapt. So what we see is this sort of cyclical problem where they are most at risk and most exposed but they are getting the least support in terms of being able to to improve their own circumstances and situation

Unknown 0:03I imagine there's a concern that given those relationships between climate change food insecurity conflict and just the vulnerability of the populations, that these situations are the there's likely it will be much harder to establish good governance and peaceful societies in the situate places once once conflict has started, is that something that is aligned with your experience? Yeah, I mean looking at this relationship between food scarcity and and conflict, that sort of operate possibly in a sort of causal loop and when they run around in circles, one can cause the other of course, pointing to food insecurity as a cause of conflict. is in certain circumstances complicated. It's complicated, precisely because the nature of conflict is that there are inevitably a wide variety of drivers in any particular case, from politics to personalities, and in this constellation. There's no doubt, though, that resource scarcity might in certain circumstances some more than others, be a driver towards insecurity and conflict. If you turn that paradigm around the other way, upside down a little bit and wonder about the implications of conflict. On food insecurity. I think in that space, it's relatively clear the lines of causation and certainly, there are some measures that would suggest the 2022 on the basis of available information in 2023, but about 120 million people have been pushed into food insecurity, precisely by by conflict by conflict and insecurity. On that I think it's it's important not only to pause for a moment and just recognize that or food insecurity to I mean, conflict is not likely to be the only or the sole driver. I mean, there are a range of other factors that play into the current global situation in terms of of access to food, not least of all economic environment. We're still suffering in many places from the consequences of the COVID 19 pandemic in terms of inflation, or economic or financial currency depreciation, and that's having an impact on people's capacity to purchase to buy in context, the cost of goods, which obviously directly affects food availability or food insecurity issues. And there are there are a range of other factors of course leading to food insecurity. We touched on climate change their weather events, natural disasters, are evidently having a massive impact on people's access to food. So there's there's a range of different factors, I think that that are driving towards the current global circumstances of access or lack of access to food, and they all sort of Interplay one to another. They're all connected, I think many of those, those factors, but for conflict specifically, I mean, it's quite clear that conflict can have implications through the whole of the food system from the very front end, which I suppose is sort of production of food. And it's been a concern. I think, many people the ICRC included that the conflict just simply the violence and hostilities in Ukraine will affect or has been affecting the the planting season and the capacity to produce that will continue to be the case. There are other factors, I think related to crop and food production, connected to conflict, including, for example, the implications which may potentially be quite long running of unexploded ordnance or explosive remnants of war. We know from our own experience that, you know, I feel the farmer's field littered with unexploded ordinance will be hard to access potentially for a very, very long time with great risk to the individuals concerned. That's the food production end and then the same challenges I think can apply throughout the cycle. I mean, processing of food will be dependent on infrastructure, the infrastructure still standing, do you still have the people the human capital, the resources, the expertise, to to process and prepare food between the farm and the consumer and in many cases, I think in conflict, the answer is probably no. All the way then through to transportation and distribution. And we know that the the most recent case in point is of course, the export of goods grain, particularly from the black sea ports as a result or consequence of the conflict, Ukraine and Russia and that's been a massive problem with massive global global implications. So so there's a range of different areas, I think, in which conflict evidently has a has a massive impact on on capacity to produce and therefore access very much to food. Unknown 4:47Have you seen much evidence in this regard with the, I guess, the the malicious weaponization of food or pre food inputs, things like fertilizer or fuel, or things that farmers need so they can produce the food for various actors own political ends? Unknown 5:09Yeah, the politicization of of food. The politicization sometimes, in certain cases of humanitarian action as well, are obviously of an immense concern. There's probably a number of different ways to sort of look at that discussion. I mean, evidently at the top level, there are questions related to the way that that sanctions do or don't work mean sanctions evidently, are intended to have political effect, but they can have consequences that flow on to civilian populations and in certain circumstances, fairly severe humanitarian consequences. That's a complex, delicate balancing act, I imagine of political and policy decision makers at the top level, where it comes home very much for an organization or humanitarian organization like us at the ICRC is really the interplay between the way those sanctions and certain other laws, particularly around counterterrorism, but the way those sanctions Interplay or can potentially have consequences for for principled humanitarian action, meaning to say that there is a risk sometimes that sanctions depending on how they're done, can directly impede the capacity of humanitarian actors to deliver on their humanitarian mandates and actually to to help people in need and this has been an area of concern, I think, for the ICRC and others for for quite a long time that the good news at least in our view, is that too reconcilable I mean, you can reconcile the state's interest in having sanctions in certain circumstances and, and humanitarian action by having ultimately what we would call, you know, humanitarian exemptions. So within a sanctions framework or other relevant legal frameworks, you can have an exemption that allows for impartial humanitarian activities and it's been a big effort, I think that the humanitarian community to to push for that and to keep that on the on the global and sometimes domestic agendas in recent years, and particularly, I think, following on from the events of 2001 and the sort of airpark of counterterrorism. Unknown 7:12So that's at the top level, that relationship, I think, between humanitarian action and sanctions that at the more granular level, maybe to say even armed conflict as such, yes, Ash. I mean, I think and it's a massive concern that food is weaponized. It's really is a massive concern. The examples I cited earlier have of siege in the Middle East, particularly in those years around about 2016 is a case in point and siege as a method of warfare has been with us with humanity probably for as long as as warfare has been with us. What's changed possibly over time, is that it's now increasingly difficult to see only the enemy's armed forces when one sees the enemy one tends to capture in that a large part of the civilian population with disastrous consequences. So the sort of dynamics of in de facto or real terms as has changed. And another thing that I think has changed in the intervening years is that the legal framework international legal framework, a way around the rules that that related to the conduct of siege and operations, now actually makes it very difficult to siege particularly as it affects the civilian population in a way that would be lawful and consistent with with modern law of armed conflict or international humanitarian law, amongst many, many other relevant rules. There is a prohibition frankly, off the starvation of the civilian population. And that alone, I think, would would would jeopardize the sort of legality of a lot of what we see in terms of siege in in the modern day. So access to food in that sense, I think is certainly been and continues to be weaponized to great humanitarian concern on the on the topic of the Geneva Conventions, the laws that govern armed conflict. Unknown 9:07Are there any figures you have on the frequency they have been mostly violated or violated? And if that's changing over recent years, as is the number of conflicts going on? Unknown 9:22Yeah, that's a really good question and very difficult. One of the challenges I think, with the body of law like international humanitarian law is that it's very difficult sometimes to demonstrate a sort of causation meaning to say, to demonstrate how and where that body of law works, and also conversely, to demonstrate in sort of numerical terms, how and where it doesn't work. I mean, obviously, we're deeply concerned about unfolding events, including unfolding events in these very days in terms of compliance with international humanitarian law. We've rather in recent years, sought to argue that although it's difficult to prove international humanitarian law continues to work and we've done a range of different activities to show instances or circumstances or practical examples of precisely when that body of law has been used to good positive humanitarian effect and whether it's been compliant or lawful behavior. We have a website called IHL and action which demonstrates precisely precisely that point. The challenge I think associated with it is to say, when I essential violations do not take place, what can we attribute that to? Is it attributable directly to the law? And are we even able to measure it meaning to say it's very difficult to demonstrate how many if I can put it in stark terms, how many murders did not take place, if you want to think about it, through through those terms. So, so demonstrating the sort of effectiveness of of IHL in positive terms is quite difficult, but we all know from contemporary media reporting that there are concerns about about the extent to which there is in fact compliance with with that body of law. If we turn I think, particularly to the question of IHL and food insecurity when evidently, for an organization like ours, a key point to pass would be that greater compliance with that body of law would have an impact. A positive impact on the greater challenge of food insecurity in situations of armed conflict. There's a prohibition of starvation that I mentioned, but there's a range of other relevant rules, including rules related to protection of objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population, which also include agricultural products, foodstuffs, and and the like. So if, if these rules were steadfastly assured, then the challenge of food insecurity in some complex circumstances would be would be less severe. There are similarly the rules around humanitarian action and providing for the needs of civilians. Under one's control, which would also have a significant impact on on this problem set in in many conflicts so so that area and reinforcing the law I think is is a key component of how we would work to address this this broader problem set that we're discussing. Unknown 12:19Right to Syria, and the what happened there in the height of that conflict, which was the huge migration crisis that then moved on and affected Europe and hence it made the it made all the newspapers and the headlines because it affected Europe. How common is the migration that is the result of a war, like, like the war in Syria? Are there similar things going on elsewhere in the world at the moment, they did not getting the same amount of attention as as the European migration crisis about 10 years or so got? Unknown 13:03Yeah, look, it certainly did get a lot of attention. And it was a scale. You know, half the population of Syria left Syria. I mean, it was at a particularly acute scale. And it really did draw a huge amount of attention. I mean, clearly ash displacement as a result of conflict is commonplace in many areas. I mean, there are migration routes through through parts of Africa where people are also leaving conflicts. We know from Somalia that there are many people currently, in Kenya. We've known historically, of course, out of Afghanistan, many people in places like Pakistan, so so there is almost inevitably population movement as a result of of conflict in many places. Now, whether it's happened in recent years to the scale of that which happened over a relatively short period of time in and around Syria, possibly not. But we could look for example, at the the early days of the recent escalation, of the conflict in Ukraine to point to another example of a large movement of populations, both internally domestically, but also across international borders. So I think that will always and continue to be one of the humanitarian consequences of of conflict. Yes. Unknown 14:22I know it's not directly the mandate of the National Committee, the Red Cross, but from from your opinion, is there anything you can share on what more could be done to prevent given the correlation between climate change and the geopolitical instability whether that because of weather events or disasters or because of the development of armed conflict, is there anything that you would advocate for the international community to be doing to try and prevent these these disasters and conflicts? Unknown 15:01Yeah, look, I think there's there's probably a lot that we could all be doing across a range of different issues on on the food insecurity issue specifically, I mean, in addition to sort of reaffirming the law and, and recalling that the steadfastly assured that would would have positive implications. I think other areas in which were invested and thinking about are the kind of lead for the international community to sort of make a concerted effort to identify and address potential points of disruption potential points of disruption to food availability at the Global regional and also at the at the domestic or local levels, trying to identify those points understanding where the weakness in, in food systems sit, and to develop plans or ideas or strategies to be able to, to cope with those or address or resolve those those weaknesses in in global food availability. And we all know that the international food systems are naturally particularly vulnerable. We only have to look at the case of the ever given the ship that belonged to the Evergreen group that got stuck in Suez Canal to recall that there are a number of very tight global choke points on global food supply. And of course, the one new conflict that we've discussed is particularly these days, the black sea ports and the availability of grain out of out of that area. So we know that there's there's particular particular vulnerabilities in terms of global regional and local food systems. One of the solutions, at least in part viewed very much through humanitarian lens is what's called anticipatory action, anticipatory humanitarian action as some people would call it, and that is really trying to gather to the best of our ability, all of the relevant data points be their data points on rainfall or other wet weather patterns, to try to sort of forecast to the greatest extent possible, the potential impact on amongst many other things food insecurity, and what you can do if you can use the data that's available. Share, collate that data as appropriate to build the best possible picture is you can actually put in place mechanisms to be able to sound the alarm sort of early warning systems for want of a better way to describe it. And you're also able, in the same vein to be able to put into place mechanisms or couldn't funding mechanisms to be able to address or respond to that particular outcome, if you can anticipate it coming on the horizon. And this anticipatory action I think, is particularly important as relates to food insecurity because the data points around that might make in some circumstances, it reasonably easy to predict predicting other elements of of the sort of cumulative crisis that we're discussing today. Ash are much more difficult. I mean, predicting conflict is naturally more difficult although you know, one can make efforts in that domain as as well. So, anticipatory action, addressing identifying and addressing the areas of potential concern, a key for us much more narrowly as a humanitarian organization to I think what we're really interested in doing is making sure that for food insecurity, particularly we have very targeted responses when I said targeted responses, I mean, some of those groups of people who are particularly exposed, we mentioned amongst others, those who've been displaced detainees and others, making sure that as a humanitarian responder, we're able to engage with them and address their needs specifically in the context in which we find them is going to be going to be vitally important. I mean, of course, all of this and the global challenge that we confront in this constellation of, of crises are obviously I mean, above and beyond what humanitarian actors alone are able to achieve and there needs to be a sort of global and concerted effort with the right financing and financing and financial support to address many of these challenges. But for our piece of the puzzle, that's where we're we're particularly concentrated or focused David, thank you so very much for sharing everything with us before I go, is there before we go, is there anything else that we haven't discussed that you think is worthwhile adding? Unknown 19:23No, look, I mean, I think I think the topic you're you're looking at is very important, and I think it's going to continue to be for all the wrong reasons, of course, of utmost importance to many humanitarian actors. I think one thing that we can draw out of parts of this discussion, but also the issue more generally, is just how inevitably global this problem set is and is going to become I mean, in the kind of interconnected nature of global markets. It's it's increasingly difficult to say, Oh, it's a it's another problem of another part of the world. I think we're all a little bit in this together. I mean, not least of all, of course, in the question of climate change, and its implications which we're going to have to address as a as a global issue. Be that as it may, it's evident that there are places right now who are where there are greater implications of things like food insecurity. The African continent, for example, is particularly affected with something like 150 million people currently, food insecure and within the African continent this discussion is really, I think, resurfaced in recent years, as you know, for reasons related to the eastern horn region, which has been particularly particularly heavily impacted. In all of this extra resume outside of the African continent we can, we can also put the cursor on places like Afghanistan, places like Yemen as well all conflict affected and all suffering from really severe examples of food insecurity. And in all of this constellation, I think for an organization like ours an area of concern is is the inability or the difficulty of keeping people's and global attention on some of these crises, which are decades protracted and which continue even to this day, where there are very serious humanitarian implications, but maintaining global attention and global response is often, I think, particularly difficult, so something of which we're we're very cognizant that there are many parts of the world that are very heavily affected, and that don't receive the attention that they would deserve from a humanitarian perspective. Unknown 21:34Thank you very, very much. Unknown 21:36Excellent. Thank you. Ash.